Stress and Alcohol Intake among Hispanic Adult Immigrants in the U.S. Midwest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center: Key Facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/23/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Batalova, J.; Hanna, M.; Levesque, C. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. 21 February 2021. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states-2020 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Fitzgerald, N. Acculturation, Socioeconomic status, and Health Among Hispanics. NAPA Bull. 2010, 34, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Priest, N.; Anderson, N.B. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2016, 35, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menjívar, C. Fragmented Ties: Salvadoran Immigrant Networks in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa, M.; Dillon, F.R.; Sastre, F.; Babino, R. Alcohol use among recent Latino immigrants before and after immigration to the United States. Am. J. Addict. 2013, 22, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Koya, D.L.; Egede, L.E. Association between length of residence and cardiovascular disease risk factors among an ethnically diverse group of United States immigrants. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, L.M.; Schneider, S.; Comer, B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Alcohol and the Hispanic Community. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2021. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-and-hispanic-community (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Mulia, N.; Ye, Y.; Greenfield, T.K.; Zemore, S.E. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 33, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, K.M.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Grant, B.F.; Hasin, D.S. Stress and alcohol: Epidemiologic evidence. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2012, 34, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, L.; Cerqueira, R.O.; Leclerc, E.; Brietzke, E. Stress, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in migrants: A comprehensive review. Rev. Bras. De Psiquiatr. 2017, 40, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.Á.; Sánchez, M.; Trepka, M.J.; Dillon, F.R.; Sheehan, D.M.; Rojas, P.; Kanamori, M.J.; Huang, H.; Auf, R.; De La Rosa, M. Immigration Stress and Alcohol Use Severity among Recently Immigrated Hispanic Adults: Examining Moderating Effects of Gender, Immigration Status, and Social Support. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E. Associations between Socioeconomic Factors and Alcohol Outcomes. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2016, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, S.; Maheswaran, R.; Pearson, T.; Gleeson, D. Socioeconomic deprivation, urban-rural location and alcohol-related mortality in England and Wales. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Owens, M.; Starkey, K.; Gil, C.; Armenta, K.; Maupomé, G. The VidaSana Study: Recruitment Strategies for Longitudinal Assessment of Egocentric Hispanic Immigrant Networks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babor, T.F.; Biddle-Higgins, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Organization; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Greene, K.M.; Maggs, J.L. Immigrant paradox? Generational status, alcohol use, and negative consequences across college. Addict. Behav. 2018, 87, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Wright, C.P.; Vaughn, M.G.; Clark, T.T.; Terzis, L.D.; Córdova, D. Substance use disorders among first- and second- generation immigrant adults in the United States: Evidence of an immigrant paradox? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Chideya, S.; Marchi, K.S.; Metzler, M.; Posner, S. Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA 2005, 294, 2879–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavers, V.L. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2007, 99, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.; Sherraden, M.S.; Huang, J.; Lee, E.J.; Keovisai, M. Financial Capability and Economic Security among Low-Income Older Asian Immigrants: Lessons from Qualitative Interviews. Soc. Work 2019, 64, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maupomé, G.; Marino, R.; Aguirre-Zero, O.; Ohmit, A.; Dai, S. Adaptation of the Psychological-Behavioral Acculturation Scale to a community of urban-based Mexican Americans in the United States. Ethn. Dis. 2015, 25, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Zero, O.; Goldsworthy, R.; Westerhold, C.; Maupomé, G. Identification of factors influencing engagement by adult and teen Mexican-Americans in oral health behaviors. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maupomé, G.; McConnell, W.R.; Perry, B.L. Dental problems and Familismo: Social network discussion of oral health issues among adults of Mexican origin living in the Midwest United States. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maupomé, G.; McConnell, W.R.; Perry, B.L.; Marino, R.; Wright, E.R. Psychological and behavioral acculturation in a social network of Mexican Americans in the United States and use of dental services. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2016, 44, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullen, E.L.; Perry, B.L.; Maupomé, G. “Does this look infected to you?” Social network predictors of dental help-seeking among Mexican immigrants. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2018, 20, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcote, J.; Livingston, M. Accuracy of self-reported drinking: Observational verification of ‘last occasion’ drink estimates of young adults. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011, 46, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner Nielsen, D.; Andersen, K.; Søgaard Nielsen, A.; Juhl, C.; Mellentin, A. Consistency between self-reported alcohol consumption and biological markers among patients with alcohol use disorder—A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 124, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flippen, C.A.; Farrell-Bryan, D. New Destinations and the Changing Geography of Immigrant Incorporation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Batalova, J.; Bolter, J. Central American Immigrants in the United States. 12 August 2019. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states-2017 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Sebena, R.; El Ansari, W.; Stock, C.; Orosova, O.; Mikolajczyk, R.T. Are perceived stress, depressive symptoms and religiosity associated with alcohol consumption? A survey of freshmen university students across five European countries. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2012, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| New Immigrant (n = 367) | Established Immigrant (n = 180) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality, n (%) | |||

| Central American | 175 (47.7) | 57 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| Mexican | 192 (52.3) | 123 (68.3) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 250 (68.1) | 120 (66.7) | 0.807 |

| Male | 117 (31.9) | 60 (33.3) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 33.9 (11.5) | 35.4 (10.4) | 0.146 |

| Median [Min, Max] | 32.0 [18.0, 82.0] | 35.0 [18.0, 64] | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 135 (36.8) | 59 (32.8) | 0.092 |

| Married/living as | 204 (55.6) | 108 (60.0) | |

| Divorced/separated | 18 (4.90) | 11 (6.11) | |

| Widowed | 9 (2.45) | 0 (0) | |

| Domestic partnership | 1 (0.272) | 2 (1.11) | |

| Planned length of stay, n (%) | |||

| Permanently | 96 (26.8) | 85 (47.2) | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 year | 43 (12.0) | 10 (5.56) | |

| 1–3+ years | 11 (3.08) | 2 (1.11) | |

| Unknown | 208 (58.1) | 83 (46.1) | |

| Missing data | 9 (2.5) | 0 (0) |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

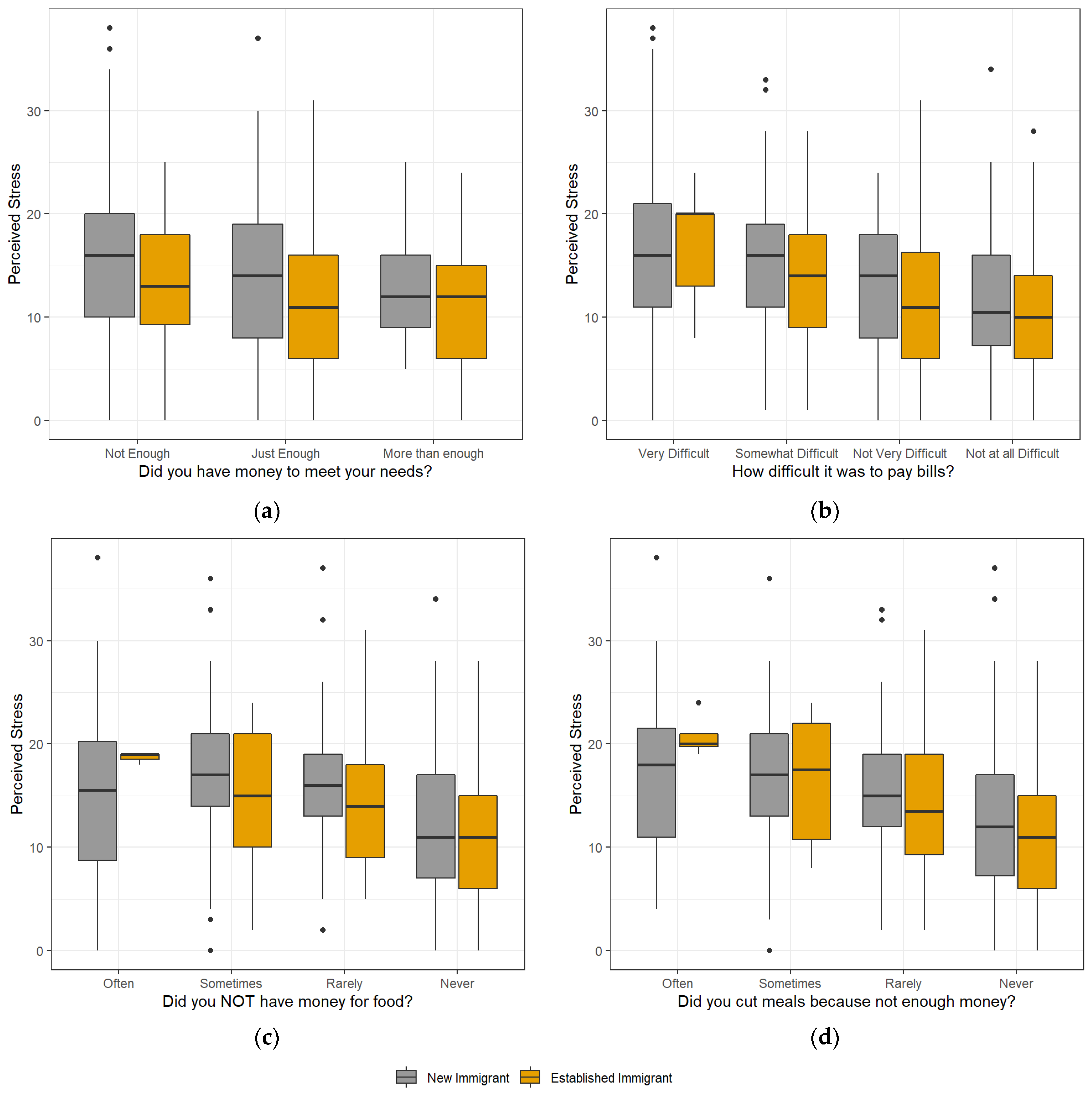

| Previous six months: money to meet needs | |||

| Not enough | - | - | |

| Just enough | −2.4 | −3.6, −1.1 | <0.001 |

| More than enough | −3.1 | −5.7, −0.60 | 0.016 |

| Previous six months: difficulty to pay bills | |||

| Very difficult | - | - | |

| Somewhat difficult | −1.7 | −3.2, −0.22 | 0.025 |

| Not very difficult | −3.8 | −5.6, −2.0 | <0.001 |

| Not at all difficult | −5.1 | −6.7, −3.6 | <0.001 |

| Previous six months: did not have money for food | |||

| Often | - | - | |

| Sometimes | 0.53 | −1.7, 2.8 | 0.643 |

| Rarely | −0.04 | −2.5, 2.3 | 0.972 |

| Never | −4.5 | −6.6, −2.4 | <0.001 |

| Previous six months: cut meals because of not enough money | |||

| Often | - | - | |

| Sometimes | −1.3 | −4.1, 1.6 | 0.385 |

| Rarely | −2.9 | −5.9, 0.15 | 0.063 |

| Never | −5.8 | −8.5, −3.1 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodriguez, J.; Golzarri-Arroyo, L.; Rodriguez, C.; Maupomé, G. Stress and Alcohol Intake among Hispanic Adult Immigrants in the U.S. Midwest. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316244

Rodriguez J, Golzarri-Arroyo L, Rodriguez C, Maupomé G. Stress and Alcohol Intake among Hispanic Adult Immigrants in the U.S. Midwest. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316244

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodriguez, Jacqueline, Lilian Golzarri-Arroyo, Cindy Rodriguez, and Gerardo Maupomé. 2022. "Stress and Alcohol Intake among Hispanic Adult Immigrants in the U.S. Midwest" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316244

APA StyleRodriguez, J., Golzarri-Arroyo, L., Rodriguez, C., & Maupomé, G. (2022). Stress and Alcohol Intake among Hispanic Adult Immigrants in the U.S. Midwest. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316244