The Landscape of Cigar Marketing in Print Magazines from 2018–2021: Content, Expenditures, Volume, Placement and Reach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.1.1. Kantar

2.1.2. MRI Simmons

2.2. Ad Content Analysis

Coding Procedures

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

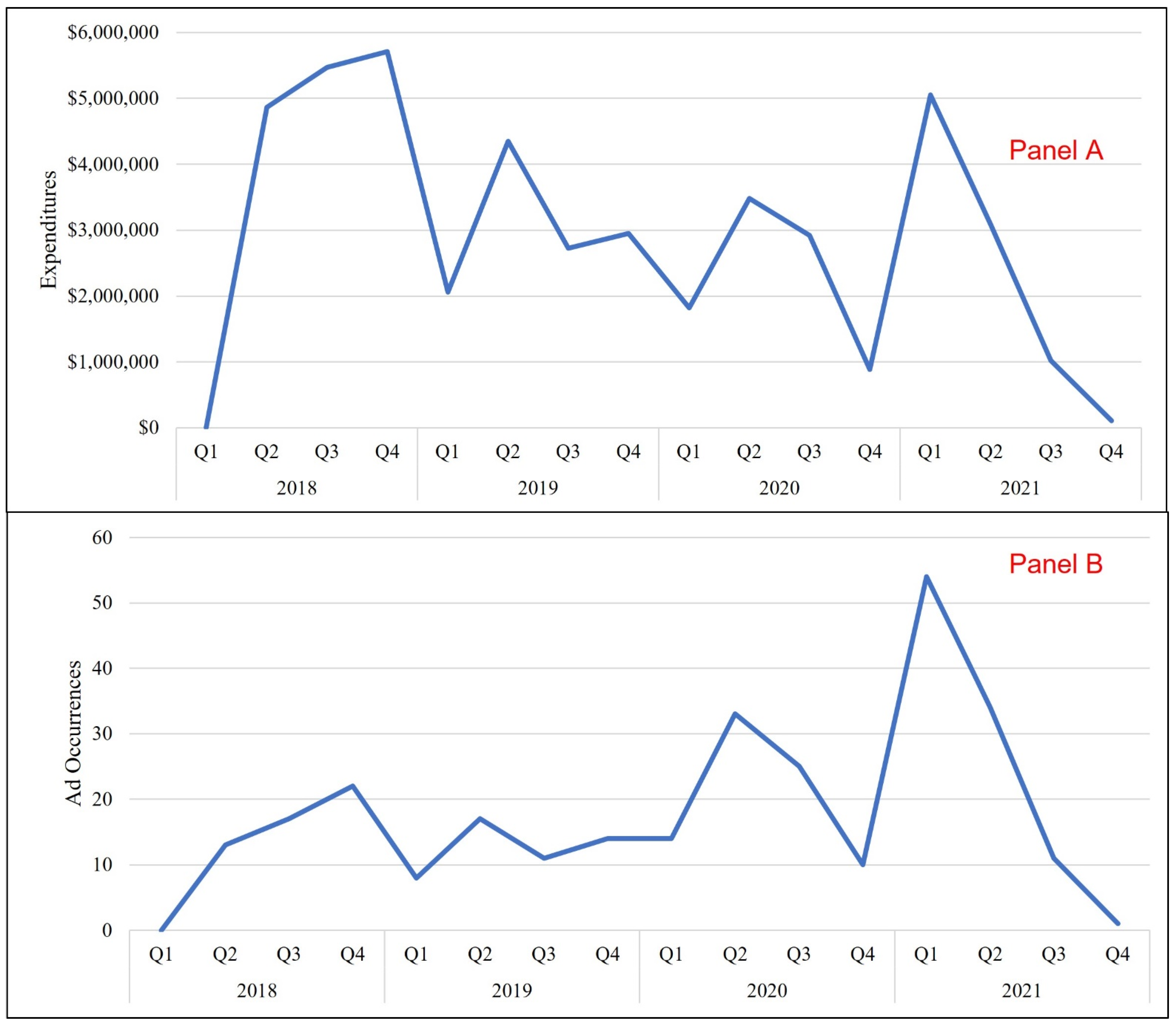

3.1. Ad Occurrences and Expenditures over Time

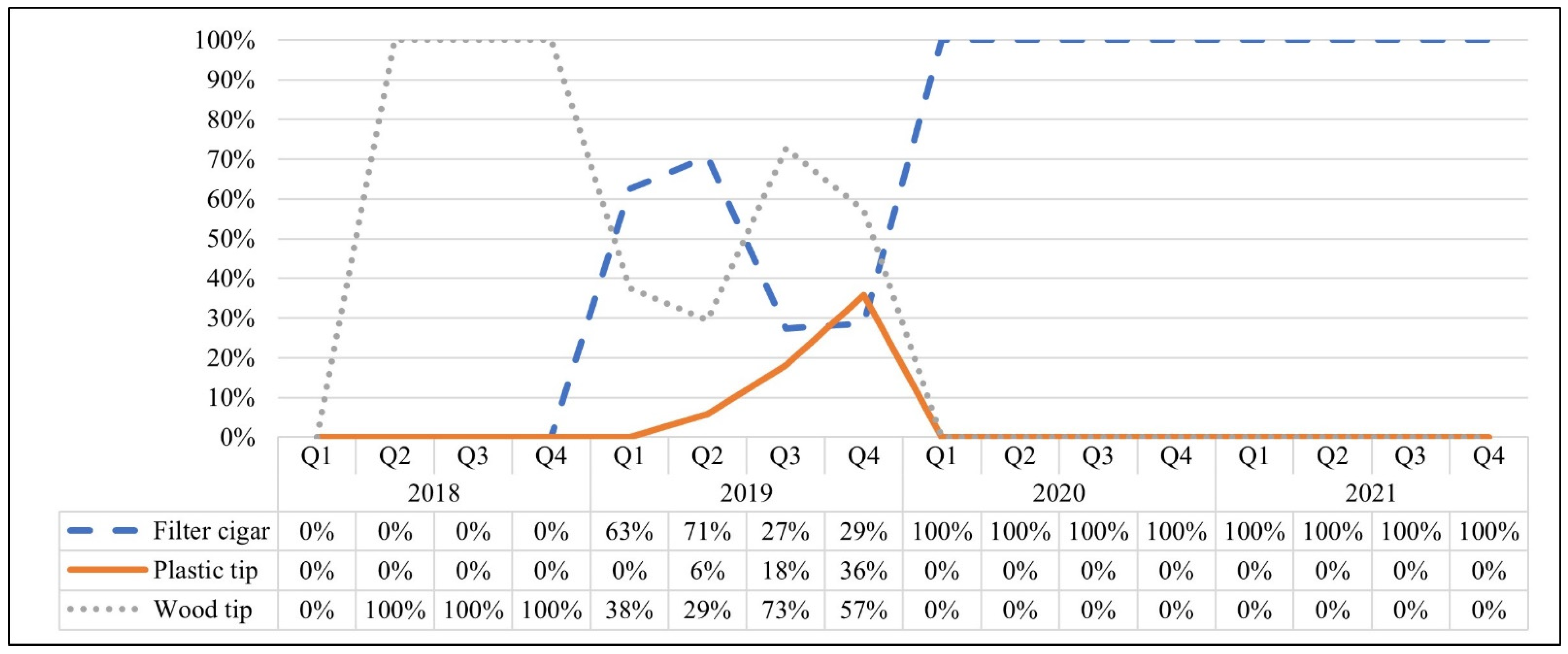

3.2. Analysis of Cigar Type over Time

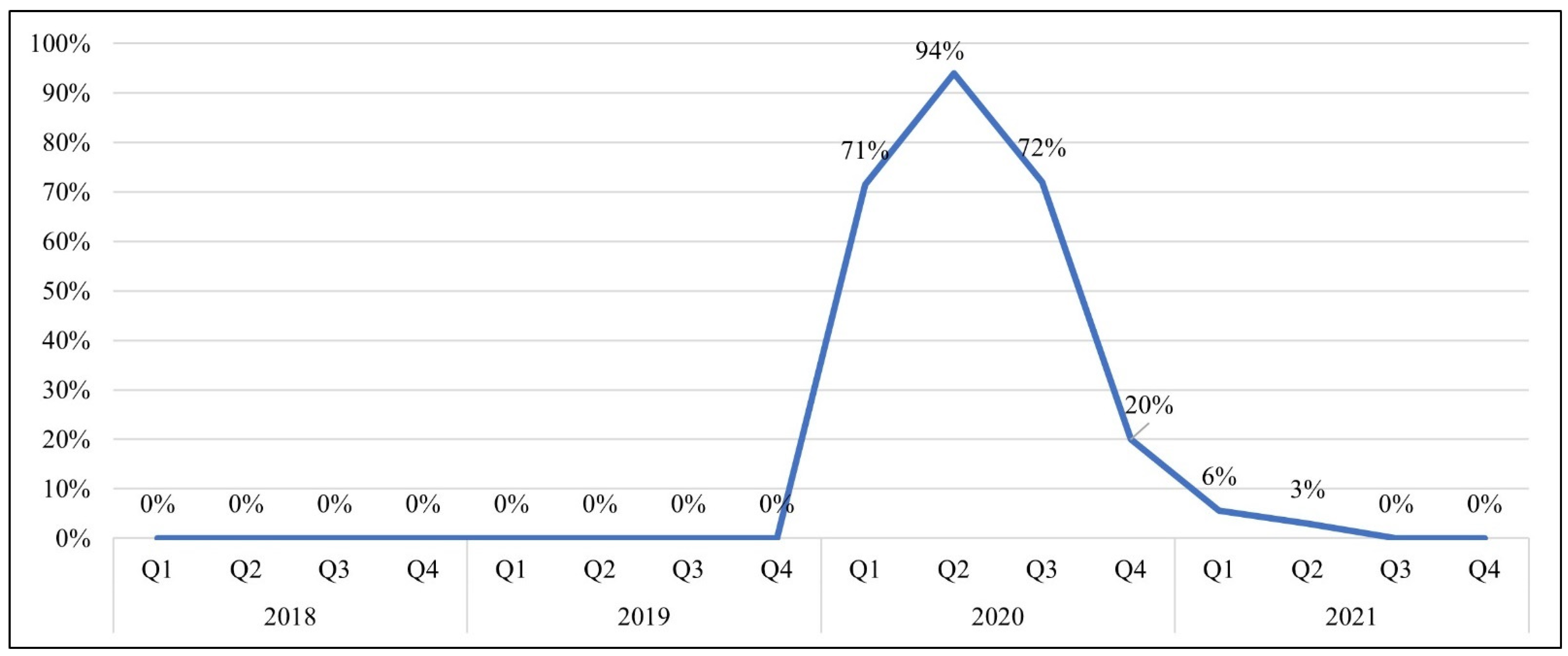

3.3. Analysis of Voluntary Compliance with FDA Warning Labels over Time

3.4. Ad Occurrences and Expenditures, by Code

3.5. Readership Data for Publications Featuring Cigar Ads

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, C.M.; Corey, C.G.; Rostron, B.L.; Apelberg, B.J. Systematic review of cigar smoking and all cause and smoking related mortality. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, J.C. The Maxwell Report: Cigar Industry in 2015; WorldCat: Richmond, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo, C.D.; Miller Lo, E.; Giovenco, D.P.; Cornacchione Ross, J.; Hrywna, M.; Strasser, A.A. Cigar Sales in Convenience Stores in the US, 2009–2020. JAMA 2021, 326, 2429–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen-Sankey, J.C.; Mead-Morse, E.L.; Le, D.; Rose, S.W.; Quisenberry, A.J.; Delnevo, C.D.; Choi, K. Cigar-Smoking Patterns by Race/Ethnicity and Cigar Type: A Nationally Representative Survey Among U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, L.; McNeel, T.S.; Choi, K. Prevalence of current large cigar versus little cigar/cigarillo smoking among U.S. adults, 2018–2019. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasza, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Conway, K.P.; Borek, N.; Taylor, K.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Cummings, K.M.; Sharma, E.; Pearson, J.L.; Green, V.R.; et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.E.; Loretan, C.G.; Wang, T.W.; Jamal, A.; Homa, D.M. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Lee, E.; Ren, C.; Cooper, M.; Cornelius, M.; Jamal, A.; Cullen, K.A. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, C.G.; Holder-Hayes, E.; Nguyen, A.B.; Delnevo, C.D.; Rostron, B.L.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Kimmel, H.L.; Koblitz, A.; Lambert, E.; Pearson, J.L.; et al. US Adult Cigar Smoking Patterns, Purchasing Behaviors, and Reasons for Use According to Cigar Type: Findings From the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013–2014. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.B.; Heley, K.; Baldwin, K.; Xiao, C.; Lin, V.; Pierce, J.P. Selling tobacco: A comprehensive analysis of the U.S. tobacco advertising landscape. Addict. Behav. 2019, 96, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, O.; Hrywna, M.; Schroth, K.R.J.; Delnevo, C.D. Innovative promotional strategies and diversification of flavoured mass merchandise cigar products: A case study of Swedish match. Tob. Control 2022, 31, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, O.; Teplitskaya, L.; Cantrell, J.; Hair, E.C.; Vallone, D. Direct-to-Consumer Marketing of Cigar Products in the United States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, O.; Rose, S.W.; Cantrell, J. Swisher Sweets ‘Artist Project’: Using musical events to promote cigars. Tob. Control 2018, 27, e93–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, W.; Brock, B.; Seth, E. ‘Kool Mixx’ remix: How Al Capone cigarillos infiltrated Hip-Hop to promote cigarillos use among African-Americans. Tob. Control 2020, 29, e159–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.K.; Hoffman, L.; Navarro, M.A.; Ganz, O. Social media use by leading US e-cigarette, cigarette, smokeless tobacco, cigar and hookah brands. Tob. Control 2020, 29, e87–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, K.L.; Vishwakarma, M.; Ababseh, K.; Henriksen, L. Flavors and Implied Reduced-Risk Descriptors in Cigar Ads at Stores Near Schools. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchione Ross, J.; Lazard, A.J.; Hedrick McKenzie, A.; Reffner Collins, M.K.; Sutfin, E.L. What Cigarillo Companies are Putting on Instagram: A Content Analysis of Swisher Sweets’ Marketing from 2013–2020. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.B.; Heley, K.; Czaplicki, L.; Weiger, C.; Strong, D.; Pierce, J. Tobacco Advertising Features That May Contribute to Product Appeal Among US Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Francis, D.B.; Bridges, C.; Sontag, J.M.; Brewer, N.T.; Ribisl, K.M. Effects of Strengthening Cigarette Pack Warnings on Attention and Message Processing: A Systematic Review. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2017, 94, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Trade Commission. FTC Announces Settlements Requiring Disclosure of Cigar Health Risks. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2000/06/ftc-announces-settlements-requiring-disclosure-cigar-health-risks (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Giovenco, D.P.; Spillane, T.E.; Talbot, E.; Wackowski, O.A.; Audrain-McGovern, J.; Ganz, O.; Delnevo, C.D. Packaging characteristics of top-selling cigars in the United States, 2018. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead-Morse, E.L.; Delnevo, C.D.; Singh, B.; Wackowski, O.A. Characteristics of Cheyenne little filtered cigar Instagram ads, 2019–2020. Tob. Control 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovenco, D.P.; Spillane, T.E.; Wong, B.A.; Wackowski, O.A. Characteristics of storefront tobacco advertisements and differences by product type: A content analysis of retailers in New York City, USA. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Cigar Labeling and Warning Statement Requirements. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/labeling-and-warning-statements-tobacco-products/cigar-labeling-and-warning-statement-requirements (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Wackowski, O.A.; Kurti, M.; Schroth, K.R.J.; Delnevo, C.D. Examination of Voluntary Compliance with New FDA Cigar Warning Label Requirements. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2020, 6, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, T.B.; Rose, S.W.; Lienemann, B.A.; Byron, M.J.; Meissner, H.I.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Huang, L.L.; Carroll, D.M.; Soto, C.; Unger, J.B. Pro-tobacco marketing and anti-tobacco campaigns aimed at vulnerable populations: A review of the literature. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2019, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 22; NIH Publication No. 17-CA-8035A; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2017.

- Tan, A.S.L.; Hanby, E.P.; Sanders-Jackson, A.; Lee, S.; Viswanath, K.; Potter, J. Inequities in tobacco advertising exposure among young adult sexual, racial and ethnic minorities: Examining intersectionality of sexual orientation with race and ethnicity. Tob. Control 2021, 30, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.Y.; Queen, T.L.; Golden, S.D.; Ribisl, K.M. Neighborhood Disparities in the Availability, Advertising, Promotion, and Youth Appeal of Little Cigars and Cigarillos, United States, 2015. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson Shen, M.; Banerjee, S.C.; Greene, K.; Carpenter, A.; Ostroff, J.S. A Content Analysis of Unique Selling Propositions of Tobacco Print Ads. Am. J. Health Behav. 2017, 41, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Association of Magazine Media. Magazine Media Factbook. Available online: https://www.magazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2021-MPA-Factbook_REVISED-NOV-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Curry, L.E.; Pederson, L.L.; Stryker, J.E. The changing marketing of smokeless tobacco in magazine advertisements. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2011, 13, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketing Charts. Digital Magazine Audience Grows, Still Lags Print. Available online: https://www.marketingcharts.com/cross-media-and-traditional/magazines-traditional-and-cross-channel-83731 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People: Disparities Details by Race and Ethnicity for 2013. 2017. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/disparities/detail/Chart/5334/3/2013 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- GfK Mediamark Research & Intellifence. 2010 Doublebase; GfK MRI: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, V.J.; Foehr, U.G.; Roberts, D.F. Generation m 2: Media in the lives of 8-to 18-year-olds. Henry J. Kais. Fam. Found. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Loukas, A.; Lewis, M.J.; Marti, C.N.; Pasch, K.E.; Perry, C.L. Tobacco Magazine Advertising Impacts Longitudinal Changes in the Number of Tobacco Products Used by Young Adults. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp LP. Stata/MP 17.1 MP for Windows; StataCorp: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Table: Population Estimates. 2 July 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Kid Count Data Center. Adult Population by Age Group in the United States. Available online: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/6538-adult-population-by-age-group#detailed/1/any/false/574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867/117,2801,2802,2803/13515,13516 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Jones, J.M. LGBT Identification in U.S. Ticks Up to 7.1%. Gallup. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Delnevo, C.D.; Jeong, M.; Ganz, O.; Giovenco, D.P.; Miller Lo, E. The Effect of Cigarillo Packaging Characteristics on Young Adult Perceptions and Intentions: An Experimental Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Wackowski, O.A.; Schroth, K.R.J.; Strasser, A.A.; Delnevo, C.D. Influence of cigarillo packaging characteristics on young adults’ perceptions and intentions: Findings from three online experiments. Tob. Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meernik, C.; Ranney, L.M.; Lazard, A.J.; Kim, K.; Queen, T.L.; Avishai, A.; Boynton, M.H.; Sheeran, P.J.; Goldstein, A.O. The effect of cigarillo packaging elements on young adult perceptions of product flavor, taste, smell, and appeal. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.J.; Ganz, O.; Jeong, M.; Wackowski, O.A.; Delnevo, C.D. Perceptions of Game cigarillo packaging among young adult tobacco users: The effect of package color and the “natural leaf” descriptor. Addict. Behav. 2022, 132, 107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.T.; Wilhelm, J.; Abudayyeh, H.; Perreras, L.; Cohn, A.M. Impact of Package Descriptors on Young Adults’ Perceptions of Cigarillos. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2020, 6, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Premium Cigars: Patterns of Use, Marketing, and Health Effects; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A. Advertising implications of the pleasure principle in the classification of products. In European Advances in Consumer Research; Van Raaij, W.F., Bamossy, G.J., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1993; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.J.; Glantz, S.A.; Ling, P.M. Emotions for sale: Cigarette advertising and women’s psychosocial needs. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanti, A.C.; Johnson, A.L.; Ambrose, B.K.; Cummings, K.M.; Stanton, C.A.; Rose, S.W.; Feirman, S.P.; Tworek, C.; Glasser, A.M.; Pearson, J.L.; et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use in Youth and Adults: Findings From the First Wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014). Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delnevo, C.D.; Hrywna, M. “A whole ‘nother smoke” or a cigarette in disguise: How RJ Reynolds reframed the image of little cigars. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Commits to Evidence-Based Actions Aimed at Saving Lives and Preventing Future Generations of Smokers; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021.

- Kowitt, S.D.; Jarman, K.L.; Cornacchione Ross, J.; Ranney, L.M.; Smith, C.A.; Kistler, C.E.; Lazard, A.J.; Sheeran, P.; Thrasher, J.F.; Goldstein, A.O. Designing More Effective Cigar Warnings: An Experiment Among Adult Cigar Smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchione Ross, J.; Lazard, A.J.; King, J.L.; Noar, S.M.; Reboussin, B.A.; Jenson, D.; Sutfin, E.L. Responses to pictorial versus text-only cigarillo warnings among a nationally representative sample of US young adults. Tob. Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratale, S.K.; Teotia, A.; Chen-Sankey, J.; Ganz, O.; Delnevo, C.D.; Strasser, A.A.; Wackowski, O.A. Cigar Warning Noticing and Demographic and Usage Correlates: Analysis from the United States Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, Wave 5. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackowski, O.A.; Jeong, M.; Schroth, K.R.J.; Rashid, M.; Delnevo, C.D. Experts’ Perceptions of and Suggestions for Cigar Warning Label Messages and Pictorials. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althubaiti, A. Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloud, R.F.; Kohler, R.E.; Viswanath, K. Cancer Risk-Promoting Information: The Communication Environment of Young Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, S63–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Proportion of Unique Ads (n = 30) | Percentage of Total Occurrences (n = 284) | Expenditures | Percentage of Total Expenditures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product characteristics | % (n) | % (n) | $ | % |

| Pack shown | 73.3 (22) | 91.5 (260) | 39,986,029 | 86.0 |

| Individual cigar(s) shown | 100 (30) | 100 (284) | 46,504,578 | 100 |

| Lit cigar(s) shown | 30.0 (9) | 40.1 (114) | 15,729,703 | 33.8 |

| Lighter, matches or ashtray shown | 13.3 (4) | 17.6 (50) | 11,557,387 | 24.8 |

| Limited edition product featured | 20.0 (6) | 7.4 (21) | 6,199,479 | 13.3 |

| Flavored cigar shown µ | 96.7 (29) | 91.2 (259) | 40,894,292 | 87.9 |

| Flavors featured | ||||

| Sweets | 66.7 (20) | 77.8 (221) | 28,732,037 | 61.8 |

| Wine | 13.3 (4) | 9.9 (28) | 8,507,698 | 18.3 |

| Jazz | 16.7 (5) | 14.8 (42) | 14,151,404 | 30.4 |

| Casino | 6.7 (2) | 5.3 (15) | 3,715,284 | 8.0 |

| Deluxe | 6.7 (2) | 1.1 (3) | 511,146 | 1.1 |

| Blues | 13.3 (4) | 2.8 (8) | 1,214,989 | 2.6 |

| Cigar type featured µ | ||||

| Filtered | 60.0 (18) | 75.5 (206) | 25,016,753 | 53.8 |

| Plastic tip | 16.7 (5) | 2.8 (8) | 1,106,896 | 2.4 |

| Wood tip | 36.7 (11) | 26.8 (76) | 21,211,145 | 45.6 |

| Ad imagery and language | ||||

| Urban imagery | 10.0 (3) | 21.5 (61) | 6,961,541 | 15.0 |

| Music-related imagery/language | 33.3 (10) | 35.2 (100) | 18,814,669 | 40.5 |

| Alcohol imagery | 3.3 (1) | 2.1 (6) | 1,887,607 | 4.1 |

| People shown in ad | 26.7 (8) | 37.3 (106) | 12,704,481 | 27.3 |

| Person shown holding/smoking/lighting cigar | 26.7 (8) | 36.6 (104) | 12,427,801 | 26.7 |

| Perceived sex of people in ad | ||||

| Male | 23.3 (7) | 19.0 (54) | 7,570,617 | 16.3 |

| Female | 10.0 (3) | 20.4 (58) | 7,021,471 | 15.1 |

| Can’t tell | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Perceived race of people in ad | ||||

| White | 10.0 (3) | 3.2 (9) | 2,595,590 | 5.6 |

| Black | 26.7 (8) | 36.6 (104) | 12,427,801 | 26.7 |

| Can’t tell | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Descriptors | ||||

| Enjoy/enjoyment | 100 (30) | 100 (284) | 46,504,578 | 100 |

| Taste | 13.3 (4) | 8.4 (24) | 4,920,595 | 10.6 |

| Aroma | 13.3 (4) | 7.0 (20) | 4,611,203 | 9.9 |

| Natural | 6.7 (2) | 4.6 (13) | 4,792,414 | 10.3 |

| Smooth | 16.7 (5) | 7.0 (20) | 3,937,063 | 8.5 |

| Short | 6.7 (2) | 2.8 (8) | 2,670,912 | 5.7 |

| Warning labels | ||||

| Warning label present | 100 (30) | 100 (284) | 46,504,578 | 100 |

| Warning label background color | ||||

| White label with black text | 76.7 (23) | 77.1 (219) | 39,443,523 | 84.8 |

| Black label with white text | 23.3 (7) | 22.9 (65) | 7,061,055 | 15.2 |

| Warning label contrast w/ad background | ||||

| Low | 23.3 (7) | 20.4 (58) | 6,724,789 | 14.5 |

| Medium | 26.7 (8) | 22.5 (64) | 9,167,675 | 19.7 |

| High | 50.0 (15) | 57.0 (162) | 30,612,114 | 65.8 |

| Voluntary compliance with FDA’s guidance for warning size/location ¶ | 23.3 (7) | 22.9 (65) | 7,061,055 | 15.2 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Language of ad | ||||

| English | 93.3 (28) | 98.9 (281) | 46,004,278 | 98.9 |

| Spanish | 6.7 (2) | 1.1 (3) | 500,300 | 1.1 |

| Link or QR code to brand website featured | 13.3 (4) | 5.6 (16) | 5,111,484 | 11.0 |

| Magazine | Number of Occurrences | Total Expenditures ($) | Total Readership | Young Adults (18–24) | Black/African American | Hispanic/Latino | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Population Total | % | Population Total | % | Population Total | % | Population Total | ||||

| In Touch Weekly | 43 | 2,395,917 | 2,975,000 | 10.9% | 324,000 | 21.8% | 649,000 | 19.4% | 576,000 | 4.3% | 127,000 |

| Life & Style Weekly | 41 | 936,567 | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ |

| Star | 23 | 3,768,680 | 3,307,000 | 11.1% | 366,000 | 25.0% | 827,000 | 18.0% | 595,000 | 5.4% | 180,000 |

| Rolling Stone | 21 | 4,332,825 | 7,226,000 | 20.0% | 1,442,000 | 16.7% | 1,205,000 | 25.0% | 1,803,000 | 6.7% | 487,000 |

| OK Weekly | 21 | 1,982,840 | 2,267,000 | 11.4% | 259,000 | 22.1% | 501,000 | 27.1% | 614,000 | 5.2% | 119,000 |

| TV Guide | 18 | 2,730,100 | 7,010,000 | 9.0% | 629,000 | 23.6% | 1,657,000 | 16.5% | 1,156,000 | 4.4% | 307,000 |

| Entertainment Weekly | 14 | 3,344,627 | 8,574,000 | 10.0% | 859,000 | 21.7% | 1,858,000 | 18.3% | 1,571,000 | 6.7% | 578,000 |

| Sports Illustrated | 12 | 5,201,200 | 11,930,000 | 13.0% | 1,554,000 | 20.5% | 2,440,000 | 15.2% | 1,817,000 | 2.8% | 335,000 |

| US Weekly | 10 | 3,032,850 | 7,362,000 | 13.6% | 1,000,000 | 18.6% | 1,371,000 | 18.5% | 1,359,000 | 6.6% | 487,000 |

| GQ | 10 | 2,481,231 | 3,952,000 | 15.3% | 604,000 | 34.1% | 1,349,000 | 21.9% | 867,000 | 10.4% | 410,000 |

| People in Español | 9 | 1,117,000 | 5,755,000 | 10.3% | 594,000 | 11.0% | 631,000 | 73.5% | 4,228,000 | 3.0% | 173,000 |

| Men’s Journal | 8 | 2,275,770 | 2,469,000 | 10.2% | 251,000 | 23.3% | 575,000 | 17.0% | 419,000 | 6.6% | 162,000 |

| Time | 7 | 2,072,182 | 11,507,000 | 11.7% | 1,342,000 | 16.5% | 1,902,000 | 17.7% | 2,041,000 | 5.8% | 670,000 |

| Popular Mechanics | 7 | 1,809,050 | 4,620,000 | 5.5% | 256,000 | 9.8% | 452,000 | 12.5% | 576,000 | 3.5% | 164,000 |

| Out | 7 | 415,343 | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ |

| Esquire | 6 | 1,600,398 | 2,061,000 | 9.3% | 192,000 | 33.9% | 698,000 | 20.6% | 424,000 | 7.0% | 144,000 |

| Golf Magazine | 5 | 1,595,580 | 3,905,000 | 6.2% | 242,000 | 9.6% | 376,000 | 8.8% | 343,000 | ¶ | ¶ |

| Popular Science | 4 | 556,880 | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ |

| In Style | 3 | 1,076,500 | 5,189,000 | 8.9% | 461,000 | 22.2% | 1,154,000 | 19.7% | 1,021,000 | 4.8% | 247,000 |

| Elle | 3 | 742,960 | 3,922,000 | 15.0% | 587,000 | 26.2% | 1,027,000 | 27.1% | 1,062,000 | 6.2% | 244,000 |

| Car and Driver | 2 | 763,965 | 5,424,000 | 6.5% | 352,000 | 11.6% | 629,000 | 16.2% | 879,000 | 3.1% | 166,000 |

| Athlon Sports & Life | 2 | 598,800 | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ | µ |

| Travel + Leisure | 2 | 531,600 | 5,071,000 | 4.6% | 233,000 | 14.6% | 741,000 | 13.4% | 680,000 | 3.8% | 195,000 |

| Vogue | 2 | 424,292 | 8,121,000 | 18.7% | 1,521,000 | 22.7% | 1,845,000 | 26.8% | 2,174,000 | 8.5% | 687,000 |

| Golf Digest | 2 | 406,277 | 3,529,000 | 4.6% | 162,000 | 8.0% | 284,000 | 5.8% | 203,000 | 1.5% | 52,000 |

| Wired | 2 | 311,144 | 2,537,000 | 12.7% | 322,000 | 11.0% | 280,000 | 17.4% | 442,000 | 6.9% | 174,000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ganz, O.; Wackowski, O.A.; Gratale, S.; Chen-Sankey, J.; Safi, Z.; Delnevo, C.D. The Landscape of Cigar Marketing in Print Magazines from 2018–2021: Content, Expenditures, Volume, Placement and Reach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316172

Ganz O, Wackowski OA, Gratale S, Chen-Sankey J, Safi Z, Delnevo CD. The Landscape of Cigar Marketing in Print Magazines from 2018–2021: Content, Expenditures, Volume, Placement and Reach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316172

Chicago/Turabian StyleGanz, Ollie, Olivia A. Wackowski, Stefanie Gratale, Julia Chen-Sankey, Zeinab Safi, and Cristine D. Delnevo. 2022. "The Landscape of Cigar Marketing in Print Magazines from 2018–2021: Content, Expenditures, Volume, Placement and Reach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316172

APA StyleGanz, O., Wackowski, O. A., Gratale, S., Chen-Sankey, J., Safi, Z., & Delnevo, C. D. (2022). The Landscape of Cigar Marketing in Print Magazines from 2018–2021: Content, Expenditures, Volume, Placement and Reach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316172