Should I Help? Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. How Does Prosocial Behaviour Develop during Crises?

1.2. Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.3. How Can We Foster More Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic?

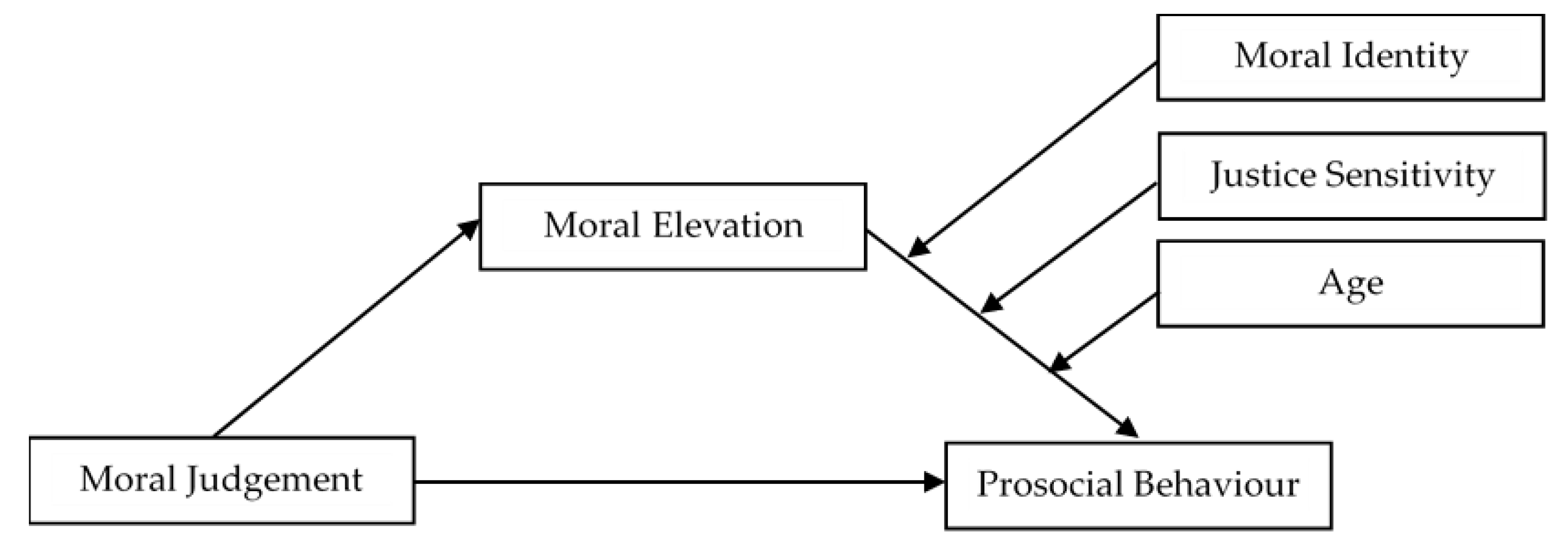

1.3.1. Moral Elevation

1.3.2. Moral Judgement

1.3.3. Moral Identity

1.4. Why Is Prosocial Behaviour Crucial in Times of Crises?

1.5. Helping One Another Is Essential during the COVID-19 Pandemic

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shillington, K.J.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Burke, S.M.; Ng, V.; Tucker, P.; Irwin, J.D. A cross-sectional examination of Canadian adults’ prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Rural Ment. Health 2022, 46, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, T.; Gorman, J.; Lee, M.; Rapp, M.; Reddem, E.R.; Yu, J.; Bahna, F.; Bimela, J. Potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies directed against spike N-terminal domain target a single supersite. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 819–833.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plümper, T.; Neumayer, E. Lockdown policies and the dynamics of the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 29, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.U.M.; Safri, S.N.A.; Thevadas, R.; Noordin, N.K.; Abd Rahman, A.; Sekawi, Z.; Ideris, A.; Sultan, M.T.H. COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia: Actions taken by the Malaysian government. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 97, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wider, W.; Taib, N.M.; Khadri, M.W.A.B.A.; Yip, F.Y.; Lajuma, S.; Punniamoorthy, P.A. The Unique Role of Hope and Optimism in the Relationship between Environmental Quality and Life Satisfaction during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.T.P.; Hadi, N.M.N.; Mohaini, M.I.; Kamu, A.; Ho, C.M.; Koh, E.B.Y.; Loo, J.L.; Theng, D.Q.L.; Wider, W. Factors Contributing to Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 in Sabah (East Malaysia). Healthcare 2022, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.S.; Sandre, P.C.; Portugal, L.C.L.; Mázala-de-Oliveira, T.; da Silva Chagas, L.; Raony, Í.; Ferreira, E.S.; Giestal-de-Araujo, E.; Dos Santos, A.A.; Bomfim, P.O.-S. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 106, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; VanSchyndel, S.K.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial motivation: Inferences from an opaque body of work. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K.; Chancellor, J.; Lyubomirsky, S. Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2014, 123, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layous, K.; Nelson, S.K.; Kurtz, J.L.; Lyubomirsky, S. What triggers prosocial effort? A positive feedback loop between positive activities, kindness, and well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Kraft, T.L.; Cross, M.P. It’s good to do good and receive good: The impact of a ‘pay it forward’style kindness intervention on giver and receiver well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Basran, J.; MacArthur, M.; Kirby, J.N. Differences in the semantics of prosocial words: An exploration of compassion and kindness. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 2259–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Holmgren, H.G.; Davis, E.J.; Collier, K.M.; Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Hawkins, A.J. A meta-analysis of prosocial media on prosocial behavior, aggression, and empathic concern: A multidimensional approach. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Carlo, G. The study of prosocial behavior: Past, present, and future. In Prosocial Development: A Multidimensional Approach; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L. Multidimensionality of prosocial behavior: Rethinking the conceptualization and development of prosocial behavior. In Prosocial Development: A Multidimensional Approach; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Niesta Kayser, D.; Greitemeyer, T.; Fischer, P.; Frey, D. Why mood affects help giving, but not moral courage: Comparing two types of prosocial behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 1136–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kong, X.; Guo, Z.; Kou, Y. Can self-compassion promote gratitude and prosocial behavior in adolescents? A 3-year longitudinal study from China. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, B.; Boyd, N. Viewing community as responsibility as well as resource: Deconstructing the theoretical roots of psychological sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 38, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.M.; Nowell, B. Psychological sense of community: A new construct for the field of management. J. Manag. Inq. 2014, 23, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J. Integrating empathy and interpersonal emotion regulation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J. The role of social identity processes in mass emergency behaviour: An integrative review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 29, 38–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R.M. Prosocial behavior increases well-being and vitality even without contact with the beneficiary: Causal and behavioral evidence. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, O.S.; Rowland, L.A.; Van Lissa, C.J.; Zlotowitz, S.; McAlaney, J.; Whitehouse, H. Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 76, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.K. The Developmental Peacebuilding Model (DPM) of children’s prosocial behaviors in settings of intergroup conflict. Child Dev. Perspect. 2020, 14, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, E.; Lubenko, J.; Presti, G.; Squatrito, V.; Constantinou, M.; Nicolaou, C.; Papacostas, S.; Aydın, G.; Chong, Y.Y.; Chien, W.T. To help or not to help? prosocial behavior, its association with well-being, and predictors of prosocial behavior during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 775032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, O.; Campos-Mercade, P.; Meier, A.N.; Wengström, E. Anticipation of COVID-19 vaccines reduces willingness to socially distance. J. Health Econ. 2021, 80, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfattheicher, S.; Nockur, L.; Böhm, R.; Sassenrath, C.; Petersen, M.B. The emotional path to action: Empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, N.L.; Klaiber, P.; Wen, J.H.; DeLongis, A. Helping amid the pandemic: Daily affective and social implications of COVID-19-related prosocial activities. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, D.M.; Dorrough, A.R.; Glöckner, A. Prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. The role of responsibility and vulnerability. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbian, T.; Adams, M.; Dooris, M.; Pool, U. The Role of Local Authorities in Shaping Local Food Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Di Virgilio, M.M. A city for all? Public policy and resistance to gentrification in the southern neighborhoods of Buenos Aires. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, N.; Henrich, J.P. Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C.B.; Norgaard, R.B.; Policansky, D. Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science 1999, 284, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatham, M.; Bauer, M.W. The state, the economy, and the regions: Theories of preference formation in times of crisis. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Vadera, A.K.; Pathki, C.S. Competition and cheating: Investigating the role of moral awareness, moral identity, and moral elevation. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E.; Kobak, R.R. Emotions system functioning and emotion regulation. In The Development of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation; Cambridge Studies in Social and Emotional Development; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Are there basic emotions? Psychol. Rev. 1992, 99, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers, J.A.; Haidt, J. Moral elevation can induce nursing. Emotion 2008, 8, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algoe, S.B.; Haidt, J. Witnessing excellence in action: The ‘other-praising’emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Aquino, K.; McFerran, B. Overcoming beneficiary race as an impediment to charitable donations: Social dominance orientation, the experience of moral elevation, and donation behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; McFerran, B.; Laven, M. Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, M.L. Toward a comprehensive empathy-based theory of prosocial moral development. In Constructive & Destructive Behavior: Implications for Family, School, & Society; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.; Fitness, J. Moral hypervigilance: The influence of disgust sensitivity in the moral domain. Emotion 2008, 8, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.K.; Haidt, J.; Nosek, B.A. Moral elevation reduces prejudice against gay men. Cogn. Emot. 2014, 28, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Vyver, J.; Abrams, D. Testing the prosocial effectiveness of the prototypical moral emotions: Elevation increases benevolent behaviors and outrage increases justice behaviors. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnall, S.; Roper, J.; Fessler, D.M. Elevation leads to altruistic behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayal, S.; Gino, F.; Barkan, R.; Ariely, D. Three principles to REVISE people’s unethical behavior. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Shao, Y.; Sun, B.; Xie, R.; Li, W.; Wang, X. How can prosocial behavior be motivated? The different roles of moral judgment, moral elevation, and moral identity among the young Chinese. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. Revisions in the theory and practice of moral development. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 1978, 1978, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.S.M.; Santos, C.M.N.C.; Bataglia, P.U.R.; Duarte, I.M.R.F. The teaching of ethics and the moral competence of medical and nursing students. Health Care Anal. 2021, 29, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Reed II, A. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford, J.M.; Hawes, D.J.; de Rosnay, M. The moral self and moral identity: Developmental questions and conceptual challenges. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 36, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A. Identity, reasoning, and emotion: An empirical comparison of three sources of moral motivation. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.; Aquino, K.; Levy, E. Moral identity and judgments of charitable behaviors. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PeConga, E.K.; Gauthier, G.M.; Holloway, A.; Walker, R.S.; Rosencrans, P.L.; Zoellner, L.A.; Bedard-Gilligan, M. Resilience is spreading: Mental health within the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Grubb, A.R.; Ebner, N.; Chirico, A.; Pizzolante, M. Increasing crisis hostage negotiator effectiveness: Embracing awe and other resilience practices. Cardozo J. Confl. Resol. 2022, 23, 615. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Newman, E.; Nelson, S.D.; Nitiéma, P.; Pfefferbaum, R.L.; Rahman, A. Disaster media coverage and psychological outcomes: Descriptive findings in the extant research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.; Sheehan, M.; Hordern, J.; Turnham, H.L.; Wilkinson, D. ‘Your country needs you’: The ethics of allocating staff to high-risk clinical roles in the management of patients with COVID-19. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 46, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, M.; Marta, E.; Marzana, D.; Gozzoli, C.; Ruggieri, R. The effect of the psychological sense of community on the psychological well-being in older volunteers. Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L.; Drury, J.; Versari, A.; Cadamuro, A. Sharing distress increases helping and contact intentions via social identification and inclusion of the other in the self: Children’s prosocial behaviour after an earthquake. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J. Together Apart: The Psychology of COVID-19; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magis, K. Community Resilience: An Indicator of Social Sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, O.; Schlösser, T. Solidarity and social justice: Effect of individual differences in justice sensitivity on solidarity behaviour. Eur. J. Personal. 2015, 29, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, R. Observed ostracism and compensatory behavior: A moderated mediation model of empathy and observer justice sensitivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 198, 111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, A.; Schmitt, M. Justice Sensitivity. In Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Sabbagh, C., Schmitt, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, M.; Platzer, C.; Zwarg, C.; Göritz, A.S. Public acceptance of COVID-19 lockdown scenarios. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; An, Z.; Zhao, P. Elderly mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploration in Kunming, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 96, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figliozzi, M.; Unnikrishnan, A. Exploring the impact of socio-demographic characteristics, health concerns, and product type on home delivery rates and expenditures during a strict COVID-19 lockdown period: A case study from Portland, OR. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 153, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Levi, N.; Fuentes, L.; Ramirez, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Señoret, A. Urban sustainability and perceived satisfaction in neoliberal cities. Cities 2022, 126, 103647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montada, L.; Schneider, A. Justice and emotional reactions to victims. Soc. Justice Res. 1988, 3, 313–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.-J.; Jung, J.C. Does social exclusion cause people to make more donations? J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2018, 5, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L. There is nothing new under the sun: Ageism and intergenerational tension in the age of the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisner, B.A. Are you OK, Boomer? Intensification of ageism and intergenerational tensions on social media amid COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X. Media representation of older people’s vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, L. Satisfaction with aging results in reduced risk for falling. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, L.; Peisah, C.; de Mendonça Lima, C.; Verbeek, H.; Rabheru, K. Ageism and the state of older people with mental conditions during the pandemic and beyond: Manifestations, etiology, consequences, and future directions. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, J.; Nitschke, J.P.; Lamm, C.; Lockwood, P.L. Older adults across the globe exhibit increased prosocial behavior but also greater in-group preferences. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, P. Chinese Woman Refuses to Wear Face Mask Amid Coronavirus Crisis. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7944045/Chinese-woman-confronted-police-refusing-wear-face-mask-coronavirus-outbreaks.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Hubbard, J.; Harbaugh, W.T.; Srivastava, S.; Degras, D.; Mayr, U. A general benevolence dimension that links neural, psychological, economic, and life-span data on altruistic tendencies. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, L. Older People Would Rather Die than Let COVID-19 Harm U.S. Economy—Texas Official. The Guardian. 24 March 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/older-people-would-rather-die-than-let-covid-19-lockdownharm-us-economy-texas-official-dan-patrick (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- North, M.; Fiske, S. A prescriptive intergenerational-tension ageism scale: Succession, identity, and consumption (SIC). Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calasanti, T. Brown slime, the silver tsunami, and apocalyptic demography: The importance of ageism and age relations. Soc. Curr. 2020, 7, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, C.I.; Van Zandvoort, K.; Gimma, A.; Prem, K.; Klepac, P.; Rubin, G.J.; Edmunds, W.J. Quantifying the impact of physical distance measures on the transmission of COVID-19 in the UK. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.; An, N.; Gao, Z.; Kiprop, E.; Geng, X. Consumer food stockpiling behavior and willingness to pay for food reserves in COVID-19. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, M.; Brown, W. Prosocial Behavior in the Time of COVID-19: The Effect of Private and Public Role Models; IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen, A.W.; Falch, R.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B. Solidarity and fairness in times of crisis. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 186, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wider, W.; Lim, M.X.; Wong, L.S.; Chan, C.K.; Maidin, S.S. Should I Help? Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316084

Wider W, Lim MX, Wong LS, Chan CK, Maidin SS. Should I Help? Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316084

Chicago/Turabian StyleWider, Walton, Mei Xian Lim, Ling Shing Wong, Choon Kit Chan, and Siti Sarah Maidin. 2022. "Should I Help? Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316084

APA StyleWider, W., Lim, M. X., Wong, L. S., Chan, C. K., & Maidin, S. S. (2022). Should I Help? Prosocial Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316084