Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Education Experience

“B: Because running is something I’ve never said no to. I: Do you like doing it that much? B: Mhm. I did from school I always jumped out in the sandbox. We had sports at school in the summer and we had indoor sports in the winter. And in the winter also swimming badges. I: So you have always done sports. B: Always, mostly always.”(förges interview 1, lines 106–110)

“Are you looking for information there, too? On the subject of health? (B: No.) Why not? (B: No.) No. Why don’t you do that? B: On television, there’s health. And we always watch that a lot.”(Geko interview 7, lines 293–295)

“[…] my books have good advice even when stress is, you should go conflicts completely out of the way, is even in my book in it and that is actually also very interesting. There you also learn to appreciate yourself, how strong are really the body language. Because body language also says something.”(Geko interview 6, lines 316–321)

3.2. Interpersonal Relationships

“B: Yes, even very much. My caregiver K (? K) also paid a lot of attention to that and I fully agree with her and I also do that without …#00:10:06#. She also says, A, we have to see what is good for you and your health, so that your body and your lungs are not overstrained, as they basically already are. So that I also take light things, half fat, half calories and so on. Vegetables and so on.”(Geko interview 9, lines 121–127)

“Unless a supervisor comes in and motivates me a bit. But then I do it, too. (I: What do you mean, motivates you?) If a supervisor says, yes, will you come out with me? Then they try to motivate me. Because during the winter I really, really don’t like to go outside. […]. So they try to motivate me a little bit. So it works from time to time.”(förges interview 6, line 112)

“I: But when you do exercise, you’d rather do it alone or with-. B: I’m happy when my wife is there. I: So that means you are quite a good team. B: Yes. I: So you are quite a good sports team. B: Of course. With Paderborn pants and Paderborn jersey.”(förges interview 2, lines 174–179)

“B1: Yes, I still have a few friends who do sports with me. I’m not there alone. I: And these are the girlfriends who are here or just friends like that? B1: Yes, a friend of E’s who comes from E. I: Yes, and that’s your meeting place there, so to speak? B1: Meeting place, yes so that we do sports.”(förges interview 13, lines 69–73)

3.3. Organizational and Social Structures

“I: Was there then somehow, when you came to the workshop, again information, so that it-, B: Yes, we have-, I have there, where I arrived-, there I had to do a-, there they told me what I have to do. And then I-, so the one thought, yeah, I know what to do. Wash hands, disinfect hands, put on a mouth guard and I know that. Did I say, I have no problem with that, that I wash my hands now. Yes.”(Geko interview 4, lines 102–108)

“I: Yes, isn’t it? And doesn’t anyone ever come and say: “So, now get up! And now do something again!”? B: (? Yes). I: Yes, someone does? B: Yes. I: And what do you do then? For the arm? B: Arms, doing gymnastics. I: Yes. This is where you do that? B: Yes. I: At the residential facility? B: Yes. I: Ah, that’s a good idea. B: And-?”(förges interview 16, lines 450–461)

“B: Yes, (? I always make sure that I-). In the group now I have already eaten apples or so apple. And pears. And, what are they called, and banana I have also eaten so-, banana. I: Okay, that’s all-. That’s all fruit. B: Hold so fruit. We also did that once, so now in the group, … #00:12:34#. In the living group. … #00:12:39# I: Why is fruit important for you? Or for all people. But for you now let’s ask. B: Because of vitamins.”(Geko interview 10, lines 197–205)

“B: Yes. I want one of those (? H) inside now too. I want to …#00:30:28# been. I’m 29 years in here in the club. I3: Wow. What is H? B: This is also such a, am (? currently) sports club. Have I been …#00:30:39# inside now, too. I3: Wow. 29? B: Yes. 29 years. I3: There’s a boss coming over and-. B: No no. We went to Friday, there’s also such a …#00:30:51# we were there. I …#00:30:55# were also many others honored there. I3: Great. You can be proud of that. B: Yes.”(förges interview 12, lines 399–407)

“B: Because they also gave me such support. They support me, they accompany me. They call from time to time. During the Corona time, I also experienced that two or three community members also called and just wanted to hear how I was doing. So above all, the …#00:38:17#, the community, they give me the feeling that you belong to us, we like you, we love you, we are glad and grateful that we have you A.”(Geko interview 9, lines 436–441)

3.4. The Healthcare System—Professionals, Healthcare Services, and the Secondary Healthcare Market

“Yes, they have looked, they have examined me, they have also enlightened me in this way, they have also accompanied me in this way and they have said, Mr. A, if anything is wrong, we will tell you everything, we will tell you everything that you may or may not do.”(Geko interview 9, lines 219–222)

“I: Okay. And then that one could give you more clues again. B: Yes. I: Yes, so, that is, such a sheet is not at all in order. But a conversation, well, if someone says that, then that would be super. Then that’s something great. B: Yes.”(Geko interview 2, lines 185–188)

“B: Yes, doctor P is general family doctor, like doctor W, but I prefer to be with doctor P, because he knows exactly, okay G has something now, now we have to look.”(Geko interview 6, lines 499–501)

“I: Did they give you good information? Did the doctors give you the-? B: Yes, they did-. Yes, they gave me good information. I: Not well? B: Yes, they did, they informed me well. I: Ah, okay. Okay. That is, as far as this heart thing is concerned, you are informed and you know what to look for. B: Yes.”(Geko interview 10, lines 111–117)

“With my current family doctor P from T, I sometimes have the impression that he does listen to us, you can also talk to him, he’s a great guy …#00:17:13#, he only dealt with us very briefly, talked more with the staff, I don’t think that’s good.”(Geko interview 9, lines 203–206)

“I: And then I was in the hospital and the doctor, he was so fast, I didn’t understand that at all. Do you know this-. B: Yeah. Sometimes they talk so fast too, yeah.”(Geko interview 2, lines 91–92)

“I1: Did anything help you there? Was there anyone that helped you-, who helped you with those headaches? B: Yes, I think physiotherapy helped me a bit there.”(Geko interview 1, lines 195–197)

“Do you get any tips or advice from them, for example during physiotherapy, about what you can do? B: Yes. Don’t put so much strain on your back and all that. Just lifting and things like that. I2: And how did you find it? So, the tips from them? B: Yes. They are quite good.”(Geko interview 1, lines 221–226)

“B: Well, I used to work out at the gym. There I also did something for the belly. I: Yes, and who told you that it’s good there in the gym? B: But I’m not supposed to go up there anymore, because it’s too expensive.”(Geko interview 3, lines 240–243)

3.5. Meta Level—Politics and Cultural Context

“B: […] But these gravel roads, I hate them to death, I make more effort than anything else. I: Yes, but then-. As I said, that would be such an idea, that we-. So we can’t say ‘that’s a problem’ from Bielefeld. But for example what-. Mr. (? C) you probably know (B: Yes.), he could say, for example, as managing director, so from the city, they have to do something. Otherwise, that’s pretty disadvantageous. B: Yes, that one times for the handicapped times with, with hiking associations think along.”(förges interview 14, lines 57–59)

“I used to do rehab sports, but I didn’t really like it because there were only older people. And I didn’t really get along with the older people.”(förges interview 22, line 380)

“I: Dancing, gardening. B: Yes, that’s not for me! I: No, gardening is not for you, is it? B: No. Only for men! I: Is only for men!”(förges interview 16, lines 376–380)

“B: Yes, because the yes-. So I have nothing against foreigners. But sometimes they speak a foreign language. And I just don’t understand them.”(Geko interview 10, lines 357–358)

3.6. Digital Spaces

“I: […] where do you find out about it? B: Through the Internet […].”(Geko interview 6, lines 125–126)

“I2: Yes. What do you do then if you don’t understand? B: Yeah, either ask someone or just google it or something. I2: Yeah. So, you also use Google, then, so to speak? B: What? I2: You also use Google then? B: Yes. Yeah. I2: Yeah. I do that, too. And then quite a lot of information comes up on Google, doesn’t it? B: Mhm. (agreeing) I2: How do you look up that you then find the information that is good for you? B: Yeah, if that, if that’s a foreign word, I type that in and then it tells you that, right?”(Geko interview 1, lines 611–623)

“I: You have a smartphone like me, a cell phone. Do you sometimes use it to find things? B: Yes, I get everything out of the cell phone. I can’t read, but I dabble everywhere. I look here and there. It took me like two days on the cell phone to get a handle on it. Yes, I have it under control.”(Geko interview 4, lines 298–302)

“Yes, yes, so I, I inform myself via the app from Radio A. The case numbers are always shown there, the new ones. How many cases we have again or not. Every day.”(Geko interview 1, lines 61–63)

“Through the media and Facebook […].”(Geko interview 12, line 19)

4. Discussion

4.1. Political and Cultural Domains

4.2. The Healthcare System and the Secondary Healthcare Market

4.3. Organizational and Social Structures, and Interpersonal Relationships

4.4. Education Experience

4.5. Digital Spaces

4.6. Merging the Domains—A Meta-Look

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latteck, Ä-D.; Bruland, D. Inclusion of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Health Literacy: Lessons Learned from Three Participative Projects for Future Initiatives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinn, D. Review of Interventions to Enhance the Health Communication of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Communicative Health Literacy Perspective. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geukes, C.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Health literacy in people with intellectual disabilities: A mixed-method literature review. Kontakt 2018, 20, e416–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, N.S.; Voß, M.; Bruland, D.; Seidl, N.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Promoting health literacy in people with intellectual disabilities via explanatory videos: Scoping reviews. Health Promot. Int. 2021, daab193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, D. Critical health literacy health promotion and people with intellectual disabilities. Asia Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2014, 5, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P. “Health literacy is linked to literacy”: Eine Betrachtung der im Forschungsdiskurs zu Health Literacy berücksichtigten und unberücksichtigten Beiträge aus der Literacy Forschung. In Health Literacy im Kindes- und Jugendalter; Bollweg, T., Bröder, J., Pinheiro, P., Eds.; Gesundheit und Gesellschaft; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 393–415. [Google Scholar]

- Musca, D.M.; Gessler, D.; Ayre, J.; Norgaard, O.; Heuck, I.R.; Haar, S.; Maindal, T. Seeking a deeper understanding of ‘distributed health literacy’: A systematic review. Health Expect. 2021, 25, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentell, T.; Pitt, R.; Buchthal, O.V. Health Literacy in a social context: Review of Quantitative. Health Literacy Res. Pract. 2017, 1, e41–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, A.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. “With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebel, A.M. What Counts as Literacy in Health Literacy: Applying the Autonomous and Ideological Models of Literacy. Lit. Compos. Stud. 2021, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bruland, D.; Schulenkorf, T.; Nutsch, N.; Nadolny, S.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Interventions to Improve Physical Activity in Daily Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Detailed Results Presentation of a Scoping Review, 2nd ed.; University of Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A. The Problem-centered Interview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg, R. Decision-Making Ability: A Missing Link Between Health Literacy, Contextual Factors, and Health. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2022, 6, e213–e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulenkorf, T.; Sørensen, K.; Okan, O. International Understandings of Health Literacy in Childhood and Adolescence—A Qualitative-Explorative Analysis of Global Expert Interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dederich, M. Recht und Gerechtigkeit. In Behinderung und Gerechtigkeit. Heilpädagogik als Kulturpolitik; Dederich, M., Greving, H., Mürner, C., Rödler, P., Eds.; Psychosozial Verlag: Gießen, Germany, 2013; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn, D. ‘I Have to Explain to him’: How Companions Broker Mutual Understanding Between Patients with Intellectual Disabilities and Health Care Practitioners in Primary Care. Qualit. Health Res. 2022, 32, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terras, M.M.; Jarret, D.; McGregor, S.A. The Importance of Accessible Information in Promoting the Inclusion of People with an Intellectual Disability. Disabilities 2021, 1, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, S.; Dadaczynski, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Zelinka-Roitner, I.; Dietscher, C.; Bittlingmayer, U.H.; Okan, O. Organizational Health Literacy in Schools: Concept Development for Health-Literate Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathmann, K.; Lutz, J.; Richardt, A.; Salewski, L.; Vockert, T.; Zelfl, L.; Spatzier, D. Toolbox zur Stärkung der Gesundheitskompetenz in Einrichtungen der Eingliederungshilfe in den Bereichen Wohnen und Arbeiten (Version 1); University of Applied Science Fulda: Fulda, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Skoss, R. Care for People Who Need Extra Support: A Health Literacy Guide to Support the Health of People with a Cognitive Impairment or Intellectual Disability; The University of Notre Dame: Fremantle City, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman, L.; Panzer, A.M.; Kindig, D.A. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann, K.; Zelfl, L.; Kleine, A.; Dadaczynski, K. Gesundheitsbewusstsein und Gesundheitskompetenz von Menschen mit Behinderung. Prävention Und Gesundh. 2021, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Form, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

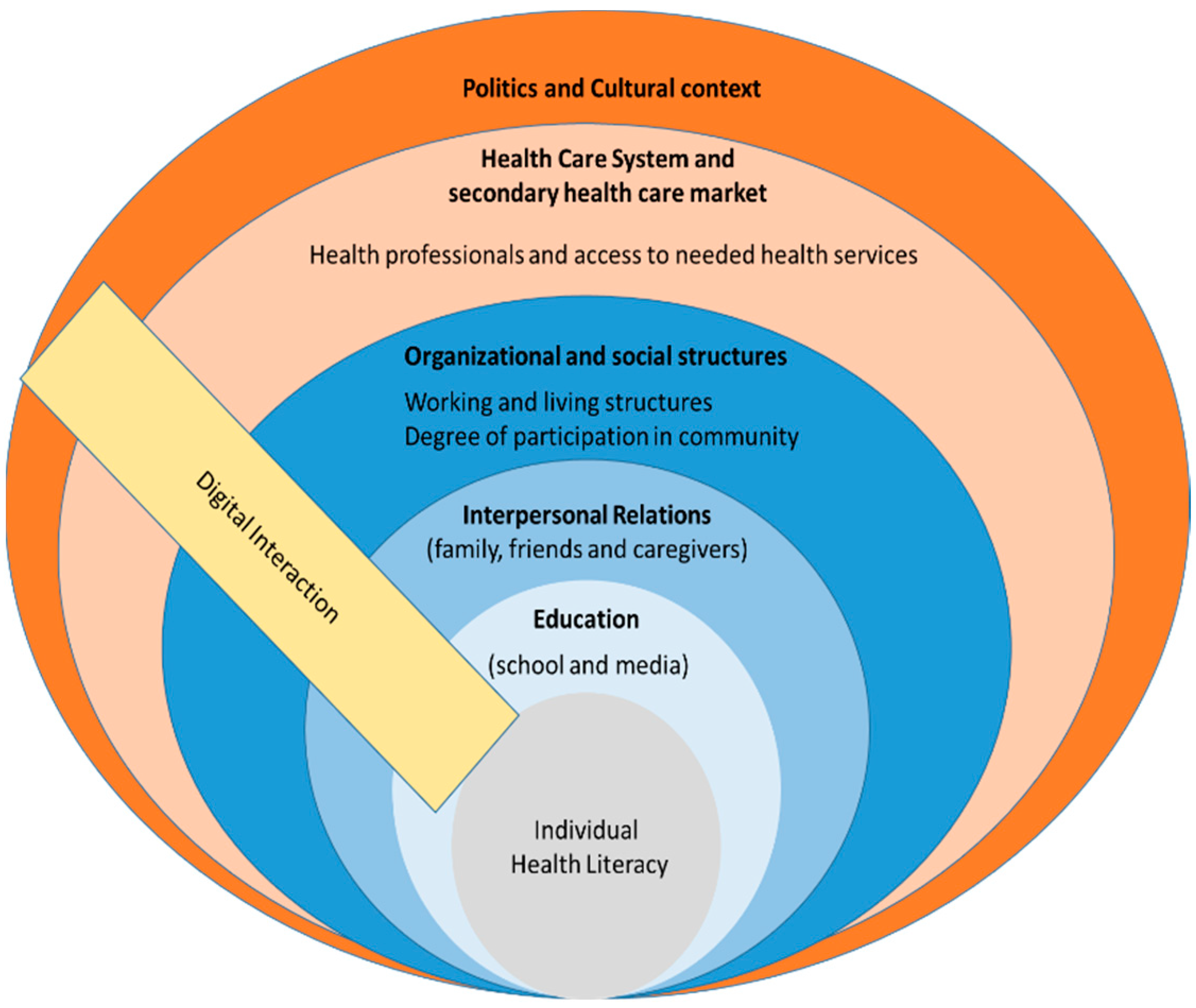

| Category | Description | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Possible education in the curriculum vitae. | ▪ School ▪ Media (television/books) |

| Interpersonal relationships | Interpersonal relationships with other individuals have a major impact on an individual’s health literacy and health behaviors. In this context, a strong dependence on other individuals is often described. | ▪ Caregivers ▪ Family or life partner ▪ Peers ▪ Neighborhood |

| Organizational and social structures | Within organizations and communities in which people interact, health-promoting dynamics emerge or exist that significantly affect individuals’ health literacy. | ▪ Work ▪ Living ▪ Association life/clubs ▪ Community |

| Healthcare system | Individuals’ health literacy often depends on their access to and contact with the healthcare system, including the people who work there (e.g., physicians) and the information provided. At the same time, barriers in the system that have a negative impact on health literacy are cited. | ▪ Healthcare workers ▪ Health services (prescribed) ▪ Secondary healthcare market |

| Politics | Policy actors rarely take into account the needs of people with disabilities, making health literacy development more difficult. | ▪ Priority local policy |

| Cultural contexts | Own value and norm conceptions, as well as intercultural differences, have an effect on the development of health literacy, such as the perception of offers. | ▪ Age ▪ Gender ▪ Language ▪ Education |

| Digital interaction spaces | The use of digital interaction spaces offers a significant opportunity to teach and to promote health literacy. | ▪ Internet ▪ App offers ▪ Smartphone/computer/tablet ▪ Social media |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vetter, N.S.; Ilskens, K.; Seidl, N.; Latteck, Ä.-D.; Bruland, D. Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316052

Vetter NS, Ilskens K, Seidl N, Latteck Ä-D, Bruland D. Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316052

Chicago/Turabian StyleVetter, Nils Sebastian, Karina Ilskens, Norbert Seidl, Änne-Dörte Latteck, and Dirk Bruland. 2022. "Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316052

APA StyleVetter, N. S., Ilskens, K., Seidl, N., Latteck, Ä.-D., & Bruland, D. (2022). Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316052