An Investigation of Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security System—A Mixed Approach Based on Regression Analysis and fsQCA

Abstract

1. Introduction

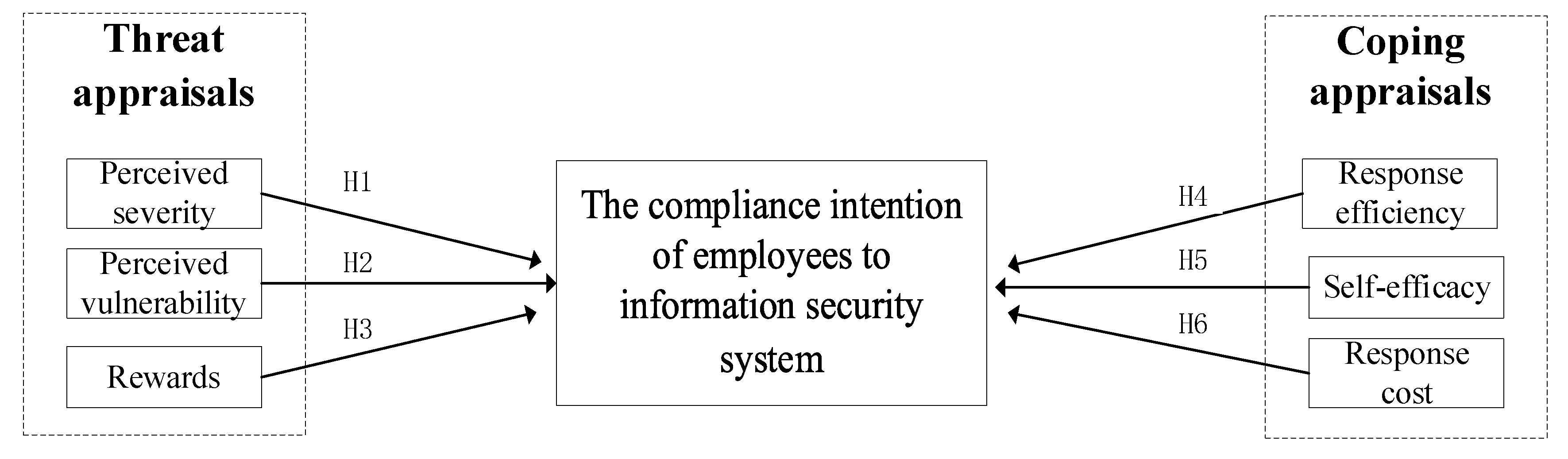

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Overview of Theory

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Regression Analysis

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Testing

3.2. Common Method Bias Test

3.3. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

3.5. Hypothesis Testing

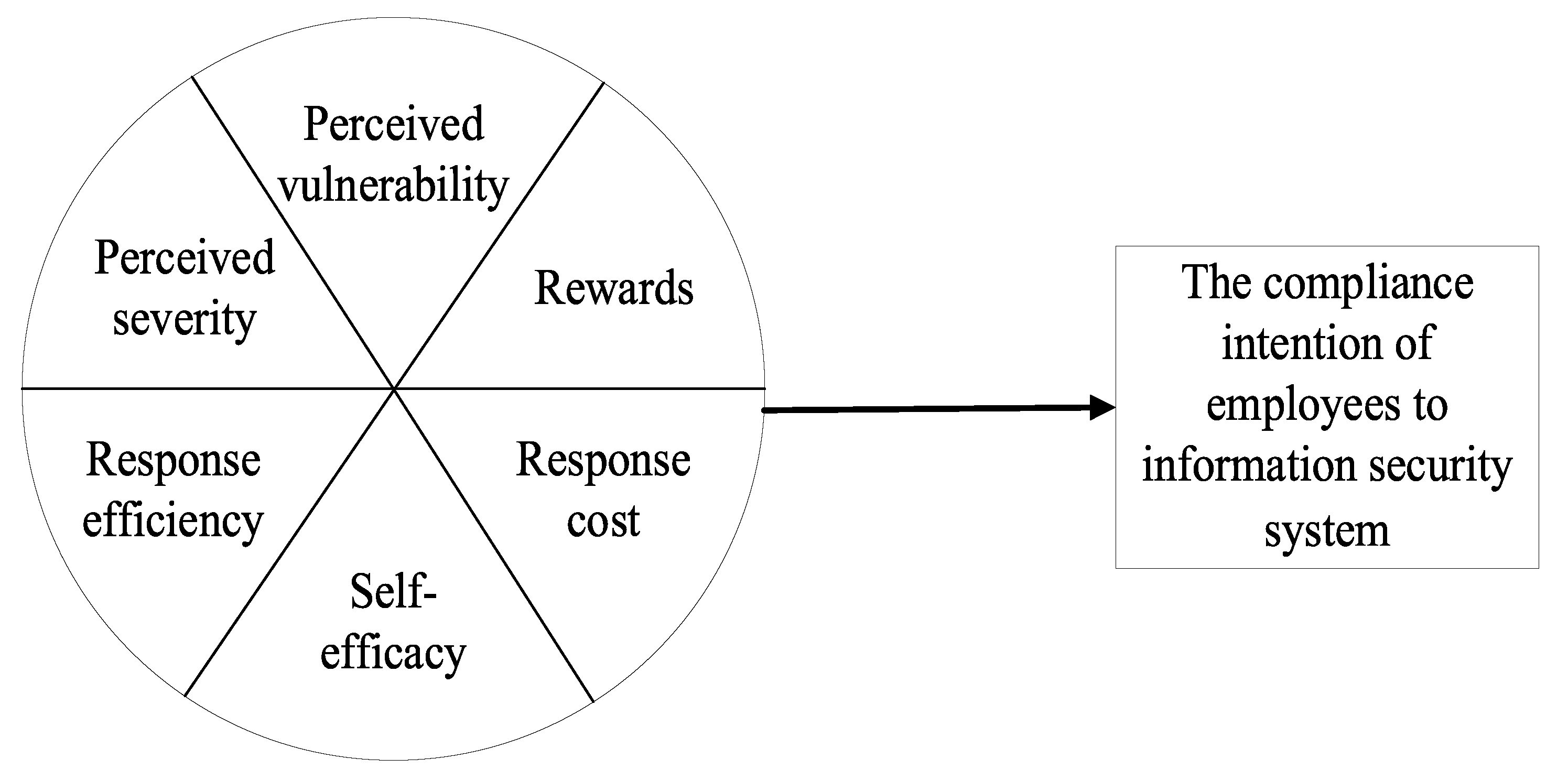

4. FsQCA of Factors Influencing Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security Systems

4.1. The Methodology of FsQCA

4.2. FsQCA Model

4.3. Data Calibration

4.4. Necessity Analysis

4.5. Sufficiency Analysis

5. Result and Discussion

5.1. Discussion of the Regression Analysis Results

5.2. Discussion of the fsQCA Results

6. Conclusions and Prospects

6.1. Reflections on Management

6.2. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Serial No. | Title Items | Likert Scale of 5 Levels | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1 | If I copy some of my company’s confidential data to unencrypted portable media (such as a USB drive), it can create serious information security problems for my company. | |||||

| 2 | If I do not comply with the information security system, the company I work for will face serious information security problems. | |||||

| 3 | For me, the loss of data privacy by not complying with the information security system is a serious issue. | |||||

| 4 | The work computer was invaded by a virus and the company’s information security system requires contacting a professional to remove the virus. If I choose to solve the virus problem myself, I can save my work time. | |||||

| 5 | The company’s information security system prohibits copying this data to unencrypted portable media (e.g., USB drives), and it saves me time at work if I copy the data to a USB drive to facilitate analysis of the data during a business trip. | |||||

| 6 | Failure to comply with the information security system saves time on the job. | |||||

| 7 | If I do not comply with the information security system, I may be exposed to information security threats. | |||||

| 8 | If I do not follow the information security system, the company I work for may have information security problems. | |||||

| 9 | The company’s information security system states that passwords are not to be shared, and if I share my password with a colleague, there may be information security issues. | |||||

| 10 | Compliance with the information security system can reduce the probability of information system security problems. | |||||

| 11 | Comply with the information security system, and there will be few information system security problems. | |||||

| 12 | Compliance with the information security system can prevent security breaches in the company’s information system. | |||||

| 13 | It is easy for me to comply with the information security system established by the company. | |||||

| 14 | I am able to consciously comply with the information security system. | |||||

| 15 | Compliance with the information security system inconveniences my daily work. | |||||

| 16 | Compliance with the information security system incurs associated administrative costs. | |||||

| 17 | Complying with the information security system not only takes time but also requires a lot of effort. | |||||

| 18 | Compliance with information security systems can be a waste of work time. | |||||

| The following six items are situational questions. In the following scenarios, choose whether you agree with what the people in the scenario are doing on the 5-point scale below. | ||||||

| 19 | Ming walks to the shared office printer alone and sees a document printed by someone else. The document is marked as “confidential”. The information security system prohibits reading confidential information, but Ming is curious and chooses to read the document. Do you agree with Ming’s action? | |||||

| 20 | Jun is browsing a website that may be problematic at work when an anti-virus program alerts him that his computer has been invaded by a virus. Although the information security system requires contacting a professional to remove the virus, Jun chooses to solve the virus problem himself for convenience. Do you agree with Jun’s approach? | |||||

| 21 | Li takes her work laptop home to work. Her children want to use the laptop to play games. Although her company’s information security system prohibits sharing the work computer with anyone. However, Li gives the laptop to her children to use. Do you agree with what Li is doing? | |||||

| 22 | Le is working in a position that requires him to know the personnel details of the company. His company’s information security system prohibits copying this data to unencrypted portable media (such as a USB drive). However, Le is on a business trip and he wants to analyze the personnel data during the trip, so he chooses to copy this data to his own portable USB drive. Do you agree with Le’s approach? | |||||

| 23 | The information security system at Hong’s company requires all users to lock their computers every time they leave them. Hong’s supervisor asks Xiaohong to unlock her computer before she leaves so that other employees can use it. So Hong unlocks the computer before she leaves. Do you agree with Hong’s approach? | |||||

| 24 | Kai uses a file server at work, which he can access by entering a password. His company’s information security system states that passwords are not to be shared. Kai is on a business trip and one of his colleagues needs the files on the file server. So Kai tells his colleague the password. Do you agree with Kai’s approach? | |||||

References

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Deng, J.; Su, C.; Gao, Z. Analysis of factors influencing miners’ unsafe behaviors in intelligent mines using a novel hybrid MCDM model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M.; Siponen, M. An enhanced fear appeal rhetorical framework: Leveraging threats to the human asset through sanctioning rhetoric. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Baskerville, R.L.; Kaul, M. Information security control theory: Achieving a sustainable reconciliation between sharing and protecting the privacy of information. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 1082–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Holm, E.; Zhai, Q. Understanding the violation of IS security policy in organizations: An integrated model based on social control and deterrence theory. Comput. Secur. 2013, 39, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, J.; Herath, T.; Shoss, M.K. Understanding employee responses to stressful information security requirements: A coping perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 31, 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.; Bommer, W.H.; Straub, D. Security lapses and the omission of information security measures: A threat control model and empirical test. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Li, W. The effects of moral disengagement and organizational ethical climate on insiders’ information security policy violation behavior. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 973–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M. How perceptions of justice affect security attitudes: Suggestions for practitioners and researchers. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2009, 17, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Understanding anti-plagiarism software adoption: An extended protection motivation theory perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Motivating IS security compliance: Insights from Habit and Protection Motivation Theory. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassaf, M.; Alkhalifah, A. Exploring the influence of direct and indirect factors on information security policy compliance: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162687–162705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, D. Factors that influence employees’ security policy compliance: An awareness-motivation-capability perspective. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2018, 58, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.-Y. Out of fear or desire? Toward a better understanding of employees’ motivation to follow IS security policies. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.L.; Agarwal, R. Practicing safe computing: A multimedia empirical examination of home computer user security behavioral intentions. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 613–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S.; Mahmood, A. Employees’ adherence to information security policies: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the IFIP TC 11 22nd International Information Security Conference, Sandton, South Africa, 14–16 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.S.; Jiang, M.; Alhabash, S.; LaRose, R.; Rifon, N.J.; Cotten, S.R. Understanding online safety behaviors: A protection motivation theory perspective. Comput. Secur. 2016, 59, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Larose, R.; Rifon, N. Keeping our network safe: A model of online protection behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2008, 27, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedadi, A.; Warkentin, M. Can secure behaviors be contagious? A two-stage investigation of the influence of herd behavior on security decisions. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 21, 428–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, T.; Rao, H.R. Protection motivation and deterrence: A framework for security policy compliance in organisations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, P.; Bott, G.J.; Crossler, R.E. User motivations in protecting information security: Protection Motivation Theory versus Self-Determination Theory. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 1203–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: An empirical study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.-S.; Kim, C.; Ryu, Y.U. Self-efficacy in information security: Its influence on end users’ information security practice behavior. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, C.; Roberts, T.L.; Lowry, P.B. The impact of organizational commitment on insiders’ motivation to protect organizational information assets. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.C.; Brennan, L.; Furnell, S. Information security burnout: Identification of sources and mitigating factors from security demands and resources. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgurcu, B.; Cavusoglu, H.; Benbasat, I. Information security policy compliance: An empirical study of rationality-based beliefs and information security awareness. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtele, S.K.; Maddux, J.E. Relative contributions of protection motivation theory components in predicting exercise intentions and behavior. Health Psychol. 1987, 6, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foth, M. Factors influencing the intention to comply with data protection regulations in hospitals: Based on gender differences in behaviour and deterrence. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bulle. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Liu, Q. The research on influencing factors of users’ personal lnformation security behavioral lntention in mobile information service. Res. Libr. Sci. 2020, 4, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnari, S.; Crilly, D.; Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Capturing causal complexity: Heuristics for configurational theorizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 46, 778–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. A set-theoretic approach to organizational configurations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1180–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevão, J.; Raposo, C. The impact of the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework Agreement on electricity prices in MIBEL: A mixed-methods approach. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.J.; Shepherd, D.A.; Prentice, C. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis for a finer-grained understanding of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M.J.; Jones, P.; Pickernell, D. The role of entrepreneurship, innovation, and urbanity-diversity on growth, unemployment, and income: US state-level evidence and an fsQCA elucidation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R.K.; Madhok, A. Overcoming the early-stage conundrum of digital platform ecosystem emergence: A problem-solving perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1899–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Pinho, J.C. A mixed methods UTAUT2-based approach to assess mobile health adoption. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Crilly, D.; Greckhamer, T. Stakeholder engagement strategies, national institutions, and firm performance: A configurational perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 1869–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F.; Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Crilly, D.; Aguilera, R. Embracing causal complexity: The emergence of a neo-configurational perspective. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C.C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 109 | 48.70 |

| Female | 115 | 51.30 | |

| Age | 30 years and below | 107 | 47.80 |

| 31 to 40 years | 44 | 19.60 | |

| 41 to 50 years | 58 | 25.90 | |

| Above 50 years | 15 | 6.70 | |

| Marital status | Married | 123 | 54.90 |

| Unmarried | 101 | 45.10 | |

| Education | Below college | 18 | 8.00 |

| College and undergraduate | 145 | 64.70 | |

| Graduate | 61 | 27.20 | |

| Work experience | 5 years or less | 101 | 45.10 |

| 6 years to 10 years | 23 | 10.30 | |

| 11 years to 15 years | 26 | 11.60 | |

| 16 years or more | 74 | 33.00 | |

| Work nature | Grass-roots staff | 151 | 67.40 |

| Middle-level grass-roots managers | 60 | 26.80 | |

| Senior managers | 13 | 5.80 | |

| Enterprise type | Software and information services industry | 65 | 29.00 |

| Not in the software and information services industry | 159 | 71.00 |

| Variable | Term | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived severity | PS1 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.84 |

| PS2 | 0.89 | ||||

| PS3 | 0.89 | ||||

| Perceived vulnerability | PV1 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.74 |

| PV2 | 0.92 | ||||

| PV3 | 0.88 | ||||

| Reward | R1 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.75 |

| R2 | 0.89 | ||||

| R3 | 0.74 | ||||

| Response efficacy | RE1 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.78 |

| RE2 | 0.87 | ||||

| RE3 | 0.82 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | SE1 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.70 |

| SE2 | 0.88 | ||||

| Response cost | RC1 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.69 |

| RC2 | 0.75 | ||||

| RC3 | 0.72 | ||||

| RC4 | 0.62 | ||||

| The compliance intention of employees with the information security system | IB1 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| IB2 | 0.86 | ||||

| IB3 | 0.87 | ||||

| IB4 | 0.87 | ||||

| IB5 | 0.73 | ||||

| IB6 | 0.83 |

| Variable | Perceived Severity | Perceived Vulnerability | Reward | Response Efficacy | Self-Efficacy | Response Cost | The Compliance Intention of Employees with the Information Security System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived severity | 0.87 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Perceived vulnerability | 0.57 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Reward | −0.38 | −0.24 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - |

| Response efficacy | 0.46 | 0.56 | −0.31 | 0.83 | - | - | - |

| Self-efficacy | 0.26 | 0.29 | −0.33 | 0.33 | 0.88 | - | - |

| Response cost | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.32 | −0.06 | −0.27 | 0.72 | - |

| The compliance intention of employees to information security system | 0.33 | 0.36 | −0.43 | 0.38 | 0.47 | −0.21 | 0.83 |

| Variable | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Perceived Severity | Perceived Vulnerability | Reward | Response Efficacy | Self-Efficacy | Response Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived severity | 3.97 | 1.01 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Perceived vulnerability | 3.98 | 0.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Reward | 2.24 | 1.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Response efficacy | 4.05 | 0.91 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Self-efficacy | 4.17 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Response cost | 2.86 | 0.89 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| The compliance intention of employees with the information security system | 4.40 | 0.81 | 0.33 *** | 0.36 *** | −0.43 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.47 *** | −0.21 ** |

| Variable | Dependent Variable: The Compliance Intention of Employees with Information Security System | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | ||

| Independent variables | Perceived severity | - | 0.26 *** | - | - | - | - | - |

| Perceived vulnerability | - | - | 0.34 *** | - | - | - | - | |

| Reward | - | - | - | −0.32 *** | - | - | - | |

| Response efficacy | - | - | - | - | 0.34 *** | - | - | |

| Self-efficacy | - | - | - | - | - | 0.47 *** | - | |

| Response cost | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.21 ** | |

| Control variables | Gender | 0.35 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.31 ** |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |

| Marital status | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.15 | −0.12 | −0.08 | |

| Education | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| Work experience | −0.09 | −0.12 | −0.16 | −0.08 | −0.17 | −0.17 | −0.10 | |

| Work nature | 0.21 | 0.25 * | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.26 * | |

| Enterprise type | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | |

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.11 | |

| ΔR2 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.07 | |

| F-value | 1.90 | 5.21 *** | 6.34 *** | 7.63 *** | 6.70 *** | 10.33 *** | 3.19 ** | |

| Antecedent Variables | IB | ~IB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| PS | 0.743281 | 0.733336 | 0.554426 | 0.415710 |

| ~PS | 0.407787 | 0.546332 | 0.644351 | 0.656058 |

| PV | 0.732438 | 0.751328 | 0.545576 | 0.425315 |

| ~PV | 0.439765 | 0.560130 | 0.681012 | 0.659204 |

| R | 0.456366 | 0.525043 | 0.768704 | 0.672105 |

| ~R | 0.714996 | 0.802669 | 0.456779 | 0.389704 |

| RE | 0.729657 | 0.733976 | 0.552038 | 0.422016 |

| ~RE | 0.425418 | 0.555481 | 0.652012 | 0.647002 |

| SE | 0.744805 | 0.777454 | 0.505711 | 0.401172 |

| ~SE | 0.426321 | 0.531596 | 0.719461 | 0.681786 |

| RC | 0.531048 | 0.604191 | 0.678882 | 0.586991 |

| ~RC | 0.636992 | 0.723008 | 0.542227 | 0.467721 |

| Conditional Configuration | The Compliance Intention of Employees to Information Security System | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| PS | |||||||

| PV | |||||||

| R | |||||||

| RE | |||||||

| SE | |||||||

| RC | |||||||

| Consistency | 0.898646 | 0.874394 | 0.892613 | 0.907320 | 0.900102 | 0.888571 | 0.878373 |

| Raw coverage | 0.468906 | 0.464805 | 0.227075 | 0.382746 | 0.412367 | 0.402617 | 0.201320 |

| Unique coverage | 0.018480 | 0.015392 | 0.012877 | 0.040809 | 0.013035 | 0.011165 | 0.009821 |

| Consistency between solutions | 0.855480 | ||||||

| Coverage between solutions | 0.630714 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Liu, R.; Sun, L.; Guo, Z.; Gao, J. An Investigation of Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security System—A Mixed Approach Based on Regression Analysis and fsQCA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316038

Li W, Liu R, Sun L, Guo Z, Gao J. An Investigation of Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security System—A Mixed Approach Based on Regression Analysis and fsQCA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316038

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenqin, Rongmin Liu, Linhui Sun, Zigu Guo, and Jie Gao. 2022. "An Investigation of Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security System—A Mixed Approach Based on Regression Analysis and fsQCA" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316038

APA StyleLi, W., Liu, R., Sun, L., Guo, Z., & Gao, J. (2022). An Investigation of Employees’ Intention to Comply with Information Security System—A Mixed Approach Based on Regression Analysis and fsQCA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316038