LGBTIQ CALD People’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. LGBTIQ CALD IPV Survivors’ Experiences of Resilience

- When a person is given a sense of purpose;

- Belief in one’s abilities;

- Developing strong social networks;

- Embracing change;

- Being optimistic;

- Nurturing oneself;

- Developing problem-solving skills;

- Establishing goals, taking action, and keep working on their skills.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

1.3. Research Questions

- How do LGBTIQ people experience survivorship and manifestations of resilience, as discussed in the peer-reviewed literature?

- How are experiences of survivorship reported on within studies concerning marginalised LGBTIQ people?

- How are experiences of coping and vulnerability as precursors for survivorship and understandings of resilience for marginalised LGBTIQ people discussed within peer-reviewed literature?

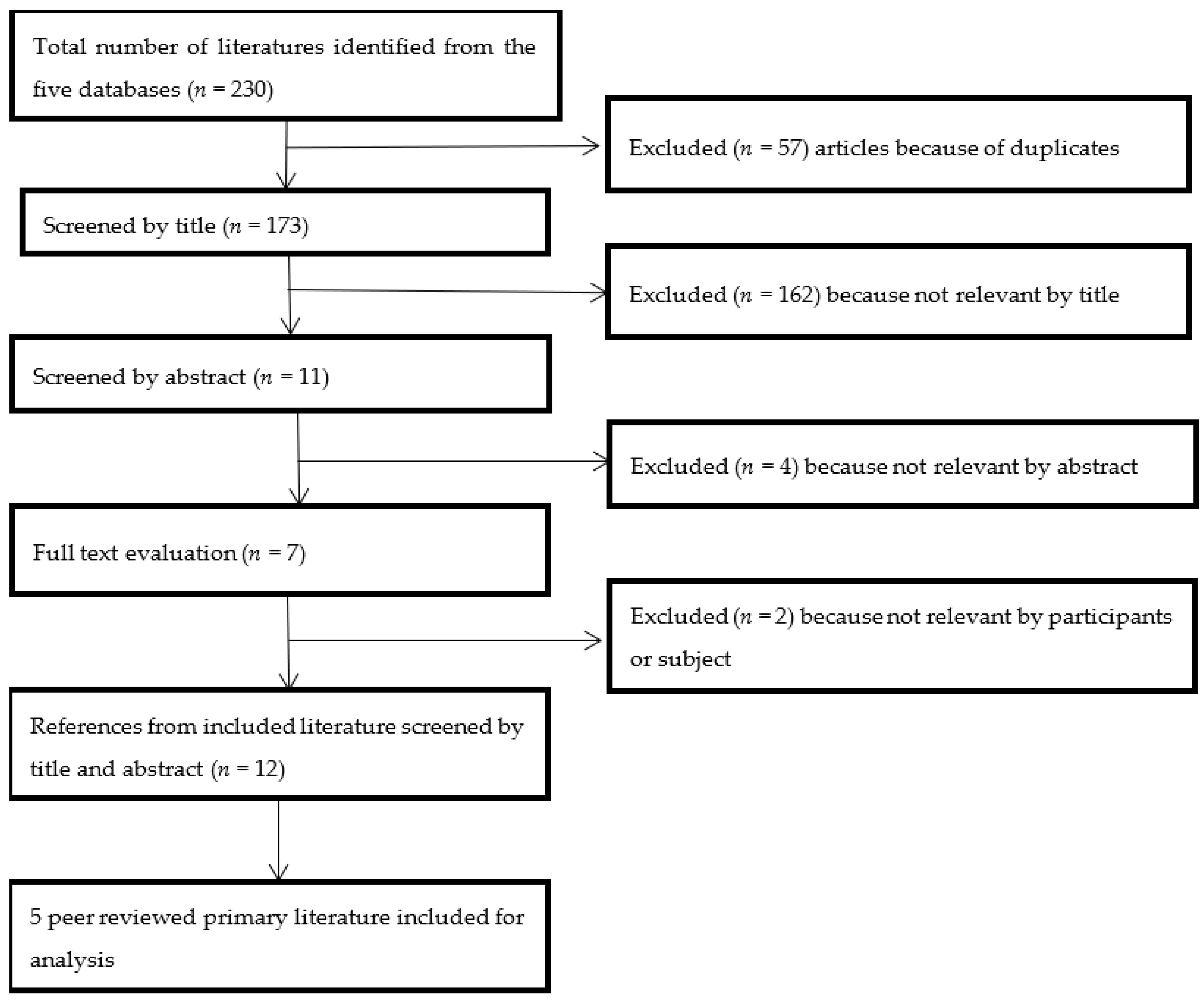

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Data Synthesis and Interpretation

2.3. Study Quality

3. Results

3.1. Research Foci and Theoretical Approach

3.2. Research Design and Methodology

4. Major Findings

4.1. Intimate Partner Violence as Experienced by LGBTIQ Survivors

4.2. Marginalised LGBTIQ Identity as Experienced by Intimate Partner Violence Survivors

4.3. Types of Survivorship as Experienced by LGBTIQ Survivors

5. Discussion

5.1. Socio-Ecological Factors and LGBTIQ Survivorship

5.2. Self and Micro Levels

5.3. Micro and Meso Levels

5.4. Exo and Macro Levels

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bates, E.; Taylor, J. Intimate Partner Violence. New Perspectives in Research and Practice, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Horsley, P.; Moussa, B.; Fisher, J.; Rees, S. Intimate partner violence and LGBTIQ people: Raising awareness in general practice. Medicine Today 2016, 17, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, A.; Dune, T. A systematic review on LGBTIQ Intimate Partner Violence from a Western perspective. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 2019, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domestic Violence Homicide in Oklahoma. Annual Report: Oklahoma Domestic Violence Fatality Review Board; 2018. Available online: https://www.oag.ok.gov/sites/g/files/gmc766/f/documents/2020/2018_dvfrb_annual_report_final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Goodman-Delahunty, J.; Crehan, A.C. Enhancing Police Responses to Domestic Violence Incidents: Reports from Client Advocates in New South Wales. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, J.M. Perpetrator or victim? A review of the complexities of domestic violence cases. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2020, 12, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.; McGowan, J.; Benier, K.; Maher, J.; Fitz-Gibbon, K. Investigating Adolescent Family Violence: Background, Research and Directions-Context Report; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, M. Heteronormativity, Homonormativity and Violence BT—Crime, Justice and Social Democracy: International Perspectives; Carrington, K., Ball, M., O’Brien, E., Tauri, J.M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.; Kruger, E.; Dune, T. Policing victims of partner violence during COVID-19: A qualitative content study on Australian grey literature. Polic. Soc. 2021, 31, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, A.; Amos, N.; Donovan, C.; Carman, M.; Parsons, M.; Lusby, S.; Lyons, A.; Hill, A.O. Naming and Recognition of Intimate Partner Violence and Family of Origin Violence Among LGBTQ Communities in Australia. J. Interpers. Violence 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.; Kuhlman, C.; Jackson, F.; Fox, P.K. Including Vulnerable Populations in the Assessment of Data from Vulnerable Populations. Front. Big Data 2019, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In Critical Race Theory; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 357–384. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, H. Intersectionality & Criminology, Disrupting and Revolutionizing Studies of Crime New Directions. In Critical Criminology; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ijoma, S. False promises of protection: Black women, trans people & the struggle for visibility as victims of intimate partner and gendered violence. Univ. Md. Law J. Race Relig. Gend. Cl. 2018, 18, 257–296. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra, G. The gendered nature of discriminatory experiences by race, class, and sexuality: A comparison of intersectionality theory and the subordinate male target hypothesis. Sex Roles 2013, 68, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.K.; Helfrich, C.A. Oppression and Barriers to Service for Black, Lesbian Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2014, 26, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Leading for Change: A Blueprint for Cultural Diversity and Inclusive Leadership Revisited. 2018. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination/publications/leading-change-blueprint-cultural-diversity-and-0 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Donovan, C.; Barnes, R. Queering Narratives of Domestic Violence and Abuse, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Formby, E. Exploring LGBT Spaces and Communities: Contrasting Identities, Belongings and Wellbeing; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Johnson, T.; Wang, Y. ‘Hidden identities’: Perceptions of sexual identity in Beijing. Br. J. Sociol. 2018, 69, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowse, L.; Rowe, S.; Baldry, E.; Baker, M. Police Responses to People with Disability. 2021. Available online: https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2021-10/Research%20Report%20-%20Police%20responses%20to%20people%20with%20disability.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Newman, R. APA’s resilience initiative. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Shamrova, D.; Han, J.B.; Levchenko, P. Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Survivors’ Help-Seeking. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 4558–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friborg, O.; Hjemdal, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Martinussen, M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2003, 12, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D. Violence Against Queer People: Race, Class, Gender and the Persistence of Anti-LGBT Discrimination; Rutgers Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, M.; Tayton, S. Intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer communities. Aust. Inst. Fam. Stud. 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, S.M.; Smith, M.; Pendrick-Denney, D.; Boos-Beddington, S.; Chen, K.; McCarty, F. Feasibility study of social media to reduce Intimate Partner Violence among gay men in Metro Atlanta, Georgia. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 13, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dune, T.; Caputi, P.; Walker, B. A systematic review of mental health care workers’ constructions about culturally and linguistically diverse people. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Waterman, E.A.; Ullman, S.E.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Dardis, C.M.; Dworkin, E.R. A Pilot Evaluation of an Intervention to Improve Social Reactions to Sexual and Partner Violence Disclosures. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, 2510–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, D.M.; Riedy Rush, C.; Hurley, K.B.; Minges, M.L. Double jeopardy: Intimate partner violence vulnerability among emerging adult women through lenses of race and sexual orientation. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 70, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ard, K.L.; Makadon, H.J. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, F.; Stone, D.M.; Tharp, A.T. Physical dating violence victimization among sexual minority youth. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e66–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitton, S.W.; Dyar, C.; Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E. Intimate Partner Violence Experiences of Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents and Young Adults Assigned Female at Birth. Psychol. Women Q. 2019, 43, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, E.G.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Mercy, J.A.; Zwi, A.B.; Lozano, R. World Report on Violence and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B. Braving the Wilderness: The Quest for True Belonging and the Courage to Stand Alone; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.D.; Erby, A.N. A Critical Analysis and Applied Intersectionality Framework with Intercultural Queer Couples. J. Homosex. 2018, 65, 1249–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | Inclusion | Exclusion | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | International | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Language | Written in English | Other Languages | Select for English Only |

| Time | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Population | Publications which focus on: people from minority or marginalized populations who identify as LGBTIQ | Publications which do not focus on: People from minority or marginalized populations who identify as LGBTIQ | TITLE: (lesbian OR gay OR bisexual OR trans* OR intersex OR queer OR LGBT* OR homosexual*Or Gender* OR sexu* OR questioning OR Gender non-conforming) AND Abstract: (Visible minority OR Visual minority OR Culturally and Linguistically Diverse OR Non-White OR ethnic minority OR racial minority OR linguistic minority OR language minority OR English as Second Language OR Language other than English OR Language Background other than English OR English as an Additional Language or Dialect) |

| Phenomena/Target | Studies concerned with resilience and intimate partner violence | Studies not concerned with resilience and intimate partner violence | AND Abstract: (resilien* OR surviv* OR grit OR self-control OR agency OR self-sufficiency OR self-determination OR victim* Or coping OR thrive OR endur* adapt* OR fragility OR vulnera* OR weakness OR rigidity) AND TITLE: (Intimate partner violence OR partner violence OR partner abuse OR psychological abuse OR financial abuse OR physical violence OR domestic violence OR family violence) |

| Study/Literature Type | Peer-reviewed primary published research academic journals | Literature not included: peer-reviewed primary published research academic journals | Not Applicable |

| No# | Author/Year | Country of Study | Sample Size | Demographics of Participants | Type of Violence | Type of Survivorship Discussed | Study Design/Data Collection Method | Data Analysis | Theoretical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edwards, Waterman, Ulman, Rodriguez, Dardis & Dworkin (2020) | USA | 1268 participants | LGBT identifying white and non-white minorities, heterosexual participants | Partner violence and sexual violence | Coping | Surveys | Chi-squares and T tests | Supporting survivors and self (SSS), attribution theory and planned behaviour theory |

| 2 | Pittman, Ridey Rush, Hurley & Minges (2020) | USA | 9435 Participants | Women of colour who identify as sexual minorities (i.e., lesbians, bisexual, etc.) | Intimate partner violence and sexual violence | Vulnerability | Self-elected National Health Assessment Data | t-tests | Intersectionality theory |

| 3 | Strasser, Smith, Pendrick-Denney, Boos-Beddington, Chen & McCarthy (2012) | USA | 100 Participants | Gay and bisexual males | Intimate partner violence | Coping | Cross-sectional surveys | Chi-square tests | Does not specify |

| 4 | Whitton, Dyar, Mustanski & Newcomb (2019) | USA | 352 Participants | Age: 16–32 Women assigned female at birth LGBT identifying. From pre-existing cohort study. | Intimate partner violence including coercive control. | Vulnerability | Pre-existing cohort study | Latent class analysis | Minority stress theory |

| 5 | Lou, Stone & Tharp (2014) | USA | 62,861 Participants | LGBTQ (questioning) white and non-white identifying | Dating violence | Coping | Does not specify | Logistic regression | Does not specify |

| Questions | Are the Results of the Study Valid? | Section A: Are the Results of the Study Valid? | Section B: What Are the Results? | Section C: Will the Results Help Locally? | AW | TD | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legend | Y-Yes/CT-Can’t Tell/N-No | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | Y/CT/N | S M W | S M W |

| No. (As per Table 2) | Author/Year | Q1. Did the study address a clearly focused issue? | Q2. Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way? | Q3. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias? | Q4. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias? | Q5A. Have the authors identified all important confounding factors? | Q5B. Have they take account of the confounding factors in the design and/or analysis? | Q6A. Was the follow up of subjects complete enough? | Q6B. Was the follow up of subjects long enough? | Q7. What are the results of this study? | Q8. How precise are the results? | Q9. Do you believe the results? | Q10. Can the results be applied to the local population? | Q11. Do the results of this study fit with other available evidence? | Q12. What are the implications of this study for practice? | ||

| 1 | Strasser et al., 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | M | M |

| 2 | Edwards et al., 2021 | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | W | W |

| 3 | Lou et al., 2014 | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | W | W |

| 4 | Whitton et al., 2019 | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M | M |

| 5 | Pittman et al., 2020 | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M | M |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Workman, A.; Kruger, E.; Micheal, S.; Dune, T. LGBTIQ CALD People’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315843

Workman A, Kruger E, Micheal S, Dune T. LGBTIQ CALD People’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315843

Chicago/Turabian StyleWorkman, Alex, Erin Kruger, Sowbhagya Micheal, and Tinashe Dune. 2022. "LGBTIQ CALD People’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315843

APA StyleWorkman, A., Kruger, E., Micheal, S., & Dune, T. (2022). LGBTIQ CALD People’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315843