Breastfeeding and Obstetric Violence during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Spain: Maternal Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

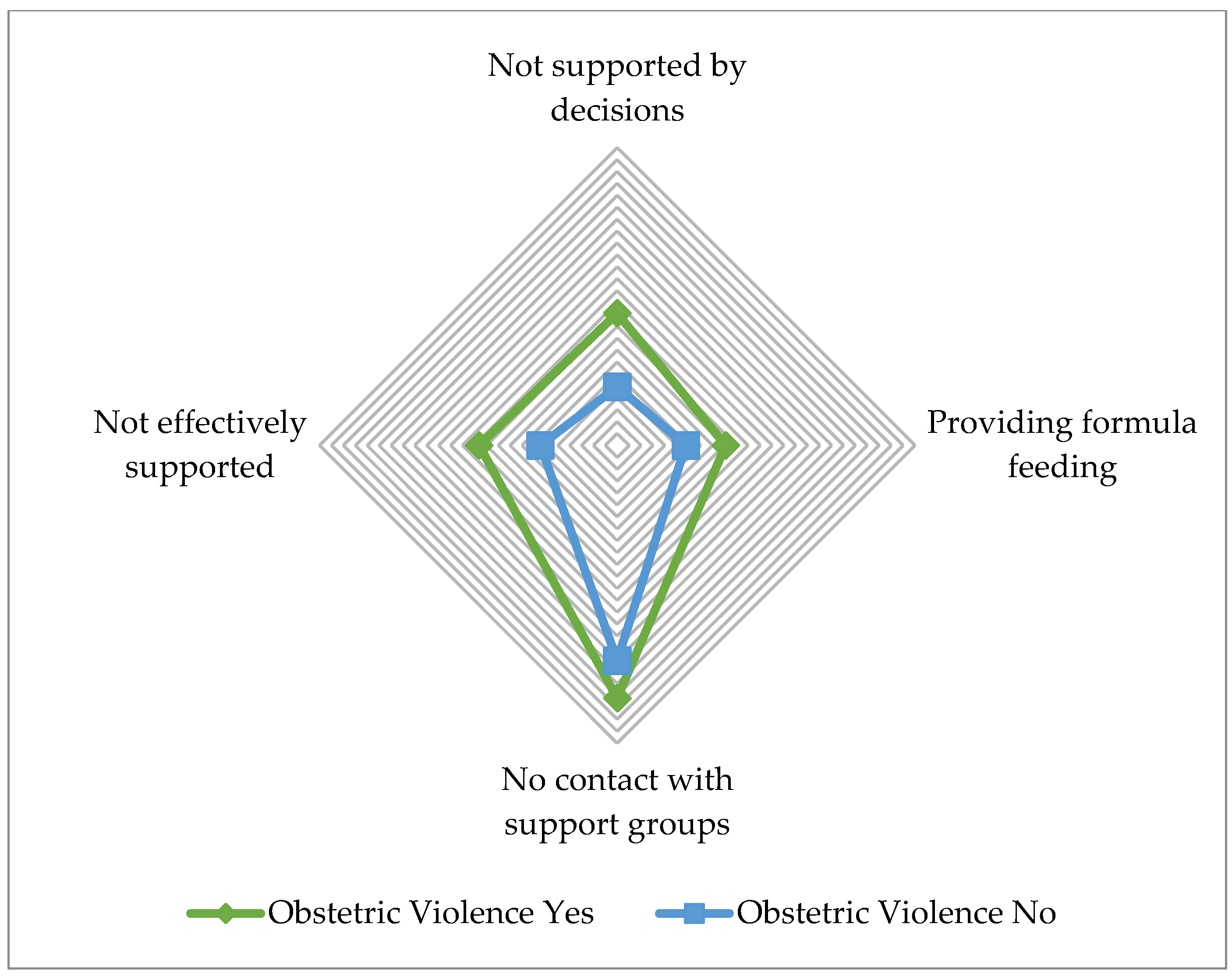

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Šimonović, D. A Human Rights-Based Approach to Mistreatment and Violence against Women in Reproductive Health Services with a Focus on Childbirth and Obstetric Violence; The United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Pérez D’gregorio, R. Obstetric violence: A new legal term introduced in Venezuela. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010, 111, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrocchi, P. Obstetric Violence Observatory: Contributions of Argentina to the International Debate. Med. Anthropol. Cross Cult. Stud. Health Illn. 2019, 38, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comunidad Autónoma de Cataluña Ley 17/2020, de 22 de Diciembre, de Modificación de la Ley 5/2008, del Derecho de las Mujeres a Erradicar la Violencia Machista 2020, 18. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2021-464 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Sadler, M.; Leiva, G.; Olza, I. COVID-19 as a risk factor for obstetric violence. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotlar, B.; Gerson, E.; Petrillo, S.; Langer, A.; Tiemeier, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Home Care for Patients with COVID-19 Presenting with Mild Symptoms and Management of Contacts: Interim Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Fox, A.; Marino, J.; Amanat, F.; Krammer, F.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Powell, R.L. Robust and Specific Secretory IgA Against SARS-CoV-2 Detected in Human Milk. iScience 2020, 23, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxon, K.; Turienzo, C.F.; Kweekel, L.; Goodarzi, B.; Brigante, L.; Simon, A.; Lanau, M.M. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on maternity care in Europe. Midwifery 2020, 88, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, C.T. Middle Range Theory of Traumatic Childbirth: The Ever-Widening Ripple Effect. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 2333393615575313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, C.T.; Watson, S. Impact of Birth Trauma on Breast-feeding. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, R.; Ayers, S.; de Visser, R. Women’s experiences of postnatal distress: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, R.M.; Colaianni, A. The impact of perinatal healthcare changes on birth trauma during COVID-19. Women Birth 2022, 35, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Cervera-Gasch, A.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part I): Women’s Perception and Interterritorial Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Cervera-Gascch, Á.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part II): Interventionism and Medicalization during Birth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casás, S.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Valero-Chilleron, M.J.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; Cervera-Gasch, Á. Obstetric Violence in Spain (Part III): Healthcare Professionals, Times, and Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Tudela, D.; Aguilar-Camprubí, L.; Quifer-Rada, P.; Paricio-Talayero, J.M.; Padró-Arocas, A. The COVID-19 vaccine in women: Decisions, data and gender gap. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma-Royo, M.; Bäuerl, C.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Aguilar-Camprubí, L.; Pérez-Cano, F.J.; Parra-Llorca, A.; Lerin, C.; Martínez-Costa, C.; Collado, M.C. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG in human milk after vaccination is dependent on vaccine type and previous SARS-CoV-2 exposure: A longitudinal study. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, C.L.C.; Ribeiro, V.S.; Nascimento, M.d.D.S.B.; Rodrigues, V.P. Association between pacifier use and bottle-feeding and unfavorable behaviors during breastfeeding. J. Pediatr. (Rio. J.) 2018, 94, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Beake, S.; Kam, J.; Lok, K.Y.W.; Bick, D. Views and experiences of women, peer supporters and healthcare professionals on breastfeeding peer support: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Midwifery 2022, 108, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranche Iparraguirre, S.; Martín Álvarez, R.; Párraga Martínez, I.; Grupo colaborativo de la Junta Permanente y Directiva de la semFYCd. El reto de la pandemia de la COVID-19 para la Atención Primaria. Rev. Clínica Med. Fam. 2021, 14, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Koleilat, M.; Whaley, S.E.; Clapp, C. The Impact of COVID-19 on Breastfeeding Rates in a Low-Income Population. Breastfedding Med. 2022, 17, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Shiri, R.; Brown, H.K.; Santos, H.P.; Schmied, V.; Falah-Hassani, K. Breastfeeding rates in immigrant and non-immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, A.O.; Dincer, E.; Karadag, N.; Topcuoglu, S.; Karatekin, G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on breastfeeding rates in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinat. Med. 2021, 49, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín Gabriel, M.A.; Manchado Perero, S.; Manzanares Gutiérrez, L.; Martín Lozoya, S.; Gómez de Olea Abad, B. COVID-19 infection in childbirth and exclusive breastfeeding rates in a BFHI maternity. An. Pediatría, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.; Shenker, N. Experiences of breastfeeding during COVID-19: Lessons for future practical and emotional support. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17e, e13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, K.; Williams, S. Women’s postpartum experiences in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. C. Open 2021, 9, E556–E562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, I.R.; Vilchez, H.S.; Cano, I.A.; Sánchez, C.M.; Dolores, M.; Giraldo, S.; Fernández, C.G.; Guisado, C.B.; Larios, F.L. Breastfeeding experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A qualitative study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quifer-Rada, P.; Aguilar-Camprubí, L.; Padró-Arocas, A.; Gómez-Sebastià, I.; Mena-Tudela, D. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic in Breastfeeding Consultations on LactApp, an m-Health Solution for Breastfeeding Support. Telemed. J. e-Health. 2022, 28, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardim, D.M.B.; Modena, C.M. Obstetric violence in the daily routine of care and its characteristics. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 2018, 26, e3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.; Carasso, K.B.; Kabakian-khasholian, T. Exposing Obstetric Violence in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Review of Women’s Narratives of Disrespect and Abuse in Childbirth. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 850796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, M.A.; Mehrtash, H.; Fawole, B.; Maung, T.M.; Balde, M.D.; Maya, E.; Thwin, S.S.; Aderoba, A.K.; Vogel, J.P.; Irinyenikan, T.A.; et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: A cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet 2019, 394, 1750–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janevic, T.; Maru, S.; Nowlin, S.; McCarthy, K.; Bergink, V.; Stone, J.; Dias, J.; Wu, S.; Howell, E.A. Pandemic Birthing: Childbirth Satisfaction, Perceived Health Care Bias, and Postpartum Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Ribeiro, D.; Calgagno Gomes, G.; Netto de Oliveira, A.M.; Quadros Alvarez, S.; Goulart Gonçalves, B.; Ferreira Acosta, D. Obstetric violence in the perception of multiparous women. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2020, 41, e20190419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solnes Miltenburg, A.; van Pelt, S.; Meguid, T.; Sundby, J. Disrespect and abuse in maternity care: Individual consequences of structural violence. Reprod. Health Matters 2018, 26, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Mir, J.; Martínez Gandolfi, A. Obstetric violence. A hidden practice in medical care in Spain. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, S.; Sivakami, M. Evidence of “obstetric violence” in India: An integrative review. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2020, 52, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Coso, E.; Miret-Gamundi, P. Characteristics of First-time Parents in Spain along the 21st Century. Rev. Española Investig. Sociol. 2017, 160, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 279 (4.6) |

| Student | 55 (0.9) |

| Unemployed | 579 (9.6) |

| Employed worker | 4423 (73) |

| Self-employed | 586 (9.7) |

| Other | 138 (2.3) |

| Level of education | |

| Basic education | 60 (1) |

| Secondary education | 1264 (20.9) |

| University education | 4736 (78.2) |

| Social class | |

| Lower | 260 (4.3) |

| Middle | 5664 (93.5) |

| Upper | 136 (2.2) |

| Race or ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 5887 (97.1) |

| Romani | 8 (0.1) |

| Black | 11 (0.2) |

| Other | 103 (1.7) |

| Type of childbirth | |

| Caesarean section | 1309 (21.6) |

| Scheduled C-section | 395 (30.18) |

| Urgent C-section | 914 (69.82) |

| Instrumental birth | 869 (14.3) |

| Vaginal birth | 3882 (64.1) |

| Type of healthcare | |

| Private healthcare | 584 (9.6) |

| Public healthcare | 3572 (58.9) |

| Mixed healthcare | 1904 (31.4) |

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 | |

| No | 5797 (95.7) |

| Yes, during pregnancy | 200 (3.3) |

| Yes, during childbirth | 63 (1) |

| Neonatal SARS-CoV-2 (n = 263) | |

| No | 255 (97) |

| Yes | 8 (3) |

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| During the postpartum period, did you feel supported in your decisions about feeding and caring for your baby? | |

| No | 1590 (27.5) |

| Yes | 3951 (68.3) |

| Do not know | 246 (4.3) |

| In which area did you feel unsupported? (n = 1590) | |

| Primary care | 381 (24.0) |

| Hospital | 1046 (65.8) |

| Both in primary care and in hospital | 163 (2.7) |

| Offered formula feeding to help her rest or because she did not have enough milk | |

| No | 3920 (69.3) |

| Yes | 1536 (27.2) |

| Do not know | 198 (3.5) |

| Were you put in contact with support groups in the area? | |

| No | 4315 (76.3) |

| Yes | 1140 (20.1) |

| Do not know | 204 (3.6) |

| Did you feel effectively supported and helped to resolve doubts or difficulties? | |

| No | 1819 (32.5) |

| Yes | 3783 (67.5) |

| Were you advised to stop breastfeeding so that you could be vaccinated against COVID-19? | |

| No | 5034 (90.6) |

| Yes | 88 (1.6) |

| Do not know | 437 (7.9) |

| Would you say you have experienced obstetric violence? | |

| No | 4030 (66.5) |

| Yes | 1578 (26.0) |

| Do not know | 452 (7.5) |

| Obstetric violence is justified by the pandemic (n = 1578) | |

| No | 1376 (87.2) |

| Yes | 57 (3.6) |

| Do not know | 145 (9.2) |

| Obstetric Violence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Do Not Know | Yes | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | X2 | df1 | p2 | |

| During the postpartum period, did you feel supported in your decisions about feeding and caring for your baby? | |||||||||||

| No | 1590 | 27.5 | 765 | 19.7 | 170 | 40.5 | 655 | 44.4 | 404.941 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Do not know | 246 | 4.3 | 140 | 3.6 | 25 | 6.0 | 81 | 5.5 | |||

| Yes | 3951 | 68.3 | 2988 | 76.8 | 225 | 53.6 | 738 | 50.1 | |||

| In which area did you feel unsupported? (n = 1590) | |||||||||||

| Primary care | 381 | 24.0 | 236 | 30.8 | 36 | 21.2 | 109 | 16.6 | 42.339 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 1046 | 65.8 | 459 | 60.0 | 121 | 71.2 | 466 | 71.1 | |||

| Both | 163 | 10.3 | 70 | 9.2 | 13 | 7.6 | 80 | 12.2 | |||

| Offered formula feeding to help her rest or because she did not have enough milk | |||||||||||

| No | 3920 | 69.3 | 2802 | 73.8 | 249 | 60.3 | 869 | 60.3 | 119.467 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Do not know | 98 | 3.5 | 123 | 3.2 | 27 | 6.5 | 48 | 3.3 | |||

| Yes | 1536 | 27.2 | 487 | 23.0 | 137 | 33.2 | 525 | 36.4 | |||

| Were you put in contact with support groups in the area? | |||||||||||

| No | 4315 | 76.3 | 2745 | 72.3 | 342 | 82.6 | 1228 | 84.9 | 108.864 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Do not know | 204 | 3.6 | 151 | 4.0 | 20 | 4.8 | 33 | 2.3 | |||

| Yes | 1140 | 20.1 | 902 | 23.7 | 52 | 12.6 | 186 | 12.9 | |||

| Did you feel effectively supported and helped to resolve doubts or difficulties? | |||||||||||

| No | 1819 | 32.5 | 969 | 25.8 | 185 | 45.5 | 665 | 46.4 | 235.522 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3783 | 67.5 | 2793 | 74.2 | 222 | 54.5 | 768 | 53.6 | |||

| Were you advised to stop breastfeeding so that you could be vaccinated against COVID-19? | |||||||||||

| No | 5034 | 90.6 | 3441 | 92.2 | 347 | 85.5 | 1246 | 88.1 | 32.940 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Do not know | 437 | 7.9 | 252 | 6.7 | 47 | 11.6 | 138 | 9.8 | |||

| Yes | 88 | 1.6 | 46 | 1.2 | 12 | 3.0 | 30 | 2.1 | |||

| Maternal SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes, during Pregnancy | Yes, during Childbirth | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | X2 | df1 | p2 | |

| During the postpartum period, did you feel supported in your decisions about feeding and caring for your baby? | |||||||||||

| No | 1590 | 27.5 | 1520 | 27.5 | 45 | 23.6 | 25 | 39.7 | 7.313 | 4 | 0.129 |

| Do not know | 246 | 4.3 | 238 | 4.3 | 7 | 3.7 | 1 | 1.6 | |||

| Yes | 3951 | 68.3 | 3775 | 68.2 | 139 | 72.8 | 37 | 58.7 | |||

| In which area did you feel unsupported? (n = 1590) | |||||||||||

| Primary care | 381 | 24.0 | 362 | 23.8 | 16 | 35.6 | 3 | 12.0 | 6.697 | 4 | 0.153 |

| Hospital | 1046 | 65.8 | 999 | 65.7 | 27 | 60.0 | 20 | 80.0 | |||

| Both | 163 | 10.3 | 159 | 10.5 | 2 | 4.4 | 2 | 8.0 | |||

| Offered formula feeding to help her rest or because she did not have enough milk | |||||||||||

| No | 3920 | 69.3 | 3747 | 69.3 | 137 | 73.3 | 36 | 58.1 | 5.358 | 4 | 0.252 |

| Do not know | 198 | 3.5 | 188 | 3.5 | 7 | 3.7 | 3 | 4.8 | |||

| Yes | 1536 | 27.2 | 1470 | 27.2 | 43 | 23.0 | 23 | 37.1 | |||

| Were you put in contact with support groups in the area? | |||||||||||

| No | 4315 | 76.3 | 4126 | 76.3 | 140 | 74.5 | 49 | 79.0 | 0.895 | 4 | 0.925 |

| Do not know | 204 | 3.6 | 196 | 3.6 | 6 | 3.2 | 2 | 3.2 | |||

| Yes | 1140 | 20.1 | 1087 | 20.1 | 42 | 22.3 | 11 | 17.7 | |||

| Did you feel effectively supported and helped to resolve doubts or difficulties? | |||||||||||

| No | 1819 | 32.2 | 1733 | 32.4 | 57 | 30.6 | 29 | 46.8 | 6.093 | 2 | 0.048 |

| Yes | 3783 | 67.5 | 3621 | 67.6 | 129 | 69.4 | 33 | 53.2 | |||

| Were you advised to stop breastfeeding so that you could be vaccinated against COVID-19? | |||||||||||

| No | 5034 | 90.6 | 4819 | 90.7 | 164 | 88.2 | 51 | 85.0 | 4.075 | 4 | 0.396 |

| Do not know | 437 | 7.9 | 410 | 7.7 | 19 | 10.2 | 8 | 13.3 | |||

| Yes | 88 | 1.6 | 84 | 1.6 | 3 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.7 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mena-Tudela, D.; Iglesias-Casas, S.; Cervera-Gasch, A.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; González-Chordá, V.M.; Valero-Chillerón, M.J. Breastfeeding and Obstetric Violence during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Spain: Maternal Perceptions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315737

Mena-Tudela D, Iglesias-Casas S, Cervera-Gasch A, Andreu-Pejó L, González-Chordá VM, Valero-Chillerón MJ. Breastfeeding and Obstetric Violence during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Spain: Maternal Perceptions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315737

Chicago/Turabian StyleMena-Tudela, Desirée, Susana Iglesias-Casas, Agueda Cervera-Gasch, Laura Andreu-Pejó, Victor Manuel González-Chordá, and María Jesús Valero-Chillerón. 2022. "Breastfeeding and Obstetric Violence during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Spain: Maternal Perceptions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315737

APA StyleMena-Tudela, D., Iglesias-Casas, S., Cervera-Gasch, A., Andreu-Pejó, L., González-Chordá, V. M., & Valero-Chillerón, M. J. (2022). Breastfeeding and Obstetric Violence during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Spain: Maternal Perceptions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15737. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315737