Construction and Validation of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL-17): A Comprehensive Short Scale to Assess the Functional, Psychosocial, and Therapeutic Factors of QOL among Stroke Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific QOL Scale (SS-QOL-17)

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Variables and Outcomes

2.4. Ethical Aspects

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Validation of the SS-QOL-17

3.3.1. Factor Analysis

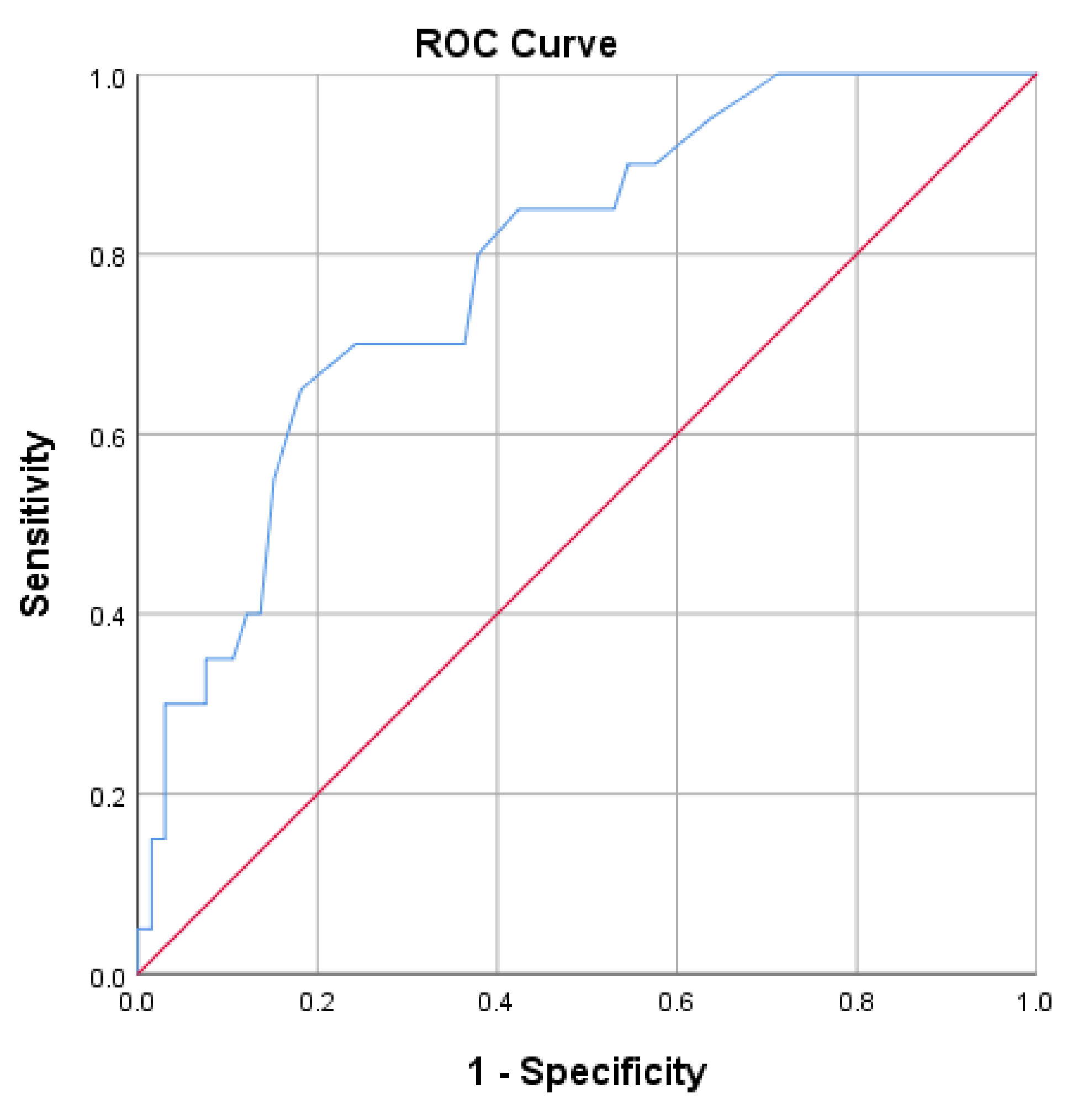

3.3.2. Validity Measures

3.4. Bivariate Analysis of Post-Stroke QOL

3.5. Predictors of Post-Stroke QOL

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Mensah, G.A. Global burden of stroke: An underestimate—Authors’ reply. Lancet 2014, 383, 1205–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talabi, O.A. A 3-year review of neurologic admissions in University College Hospital Ibadan, Nigeria. West. Afr. J. Med. 2003, 22, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.U.; Lee, H.S.; Shin, J.H.; Ho, S.H.; Koo, M.J.; Park, K.H.; Yoon, J.A.; Kim, D.M.; Oh, J.E.; Yu, S.H.; et al. Stroke Impact Scale 3.0: Reliability and Validity Evaluation of the Korean Version. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 41, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zee, C.H.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Lindeman, E.; Jaap Kappelle, L.; Post, M.W. Participation in the chronic phase of stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2013, 20, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosman, H.; Schepers, V.P.; Post, M.W.; Visser-Meily, J.M. Social activity contributes independently to life satisfaction three years post stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carod-Artal, F.J.; Egido, J.A. Quality of life after stroke: The importance of a good recovery. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2009, 27 (Suppl. S1), 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.E.; Togher, L.; Power, E.; Koh, G.C. Validation of the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale in a multicultural population. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2584–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, N.E. Stroke Rehabilitation at Home: Lessons Learned and Ways Forward. Stroke 2016, 47, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasell, R.W.; Foley, N.C.; Bhogal, S.K.; Speechley, M.R. An evidence-based review of stroke rehabilitation. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2003, 10, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.E. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Brazier, J.; Roberts, J.; Deverill, M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J. Health Econ. 2002, 21, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsman, J.; Furlong, W.; Feeny, D.; Torrance, G. The Health Utilities Index (HUI): Concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appau, A.; Lencucha, R.; Finch, L.; Mayo, N. Further validation of the Preference-Based Stroke Index three months after stroke. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, P.N.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Wakker, P.P. The utility of health states after stroke: A systematic review of the literature. Stroke 2001, 32, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.J.; Black, S.E.; Badley, E.M.; Lawrence, J.M.; Williams, J.I. Handicap in stroke survivors. Disabil. Rehabil. 1999, 21, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.F.; Wu, C.Y.; Lin, K.C.; Li, M.W.; Yu, H.W. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of a short version of the Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale in patients receiving rehabilitation. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 44, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, T.; Stucki, G. Validity of the SS-QOL in Germany and in survivors of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2007, 21, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.; Magalhaes, L.; Gomes-Neto, M. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale: Application of the Rasch model. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2008, 12, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh, I.P.; Jeng, J.S.; Lee, Y.; Sheu, C.F.; Hsieh, C.L. Construct validity of the stroke-specific quality of life questionnaire in ischemic stroke patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosman, H.; Passier, P.E.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Rinkel, G.J.; Post, M.W. Validation of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life scale in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.; Boosman, H.; van Zandvoort, M.M.; Passier, P.E.; Rinkel, G.J.; Visser-Meily, J.M. Development and validation of a short version of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2011, 82, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, R.; Ali, M.; Peters, M.; English, C.; Rodgers, H.; Jenkinson, C.; Lees, K.R.; Quinn, T.J. Derivation and Validation of a Modified Short Form of the Stroke Impact Scale. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, F.; Dabbous, M.; Akel, M.; Salameh, P.; Hosseini, H. Adherence to Post-Stroke Pharmacotherapy: Scale Validation and Correlates among a Sample of Stroke Survivors. Medicina 2022, 58, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaambwa, B.; Bulamu, N.B.; Mpundu-Kaambwa, C.; Oppong, R. Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the Barthel Index and the EQ-5D-3L When Used on Older People in a Rehabilitation Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, S.A.; Al-Khamis, F.A.; Muaidi, Q.I.; Abdulla, F.A. Translation and validation of the stroke specific quality of life scale into Arabic. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version: 2016. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/I60-I69 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Boehme, A.K.; Esenwa, C.; Elkind, M.S.V. Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawitz, A.D.; Garman, E.T.; Sorhaindo, B.; O’Neill, B.; Kim, J.; Drentea, P. The incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Establishing validity and reliability. Fin. Counsel. Plan. 2006, 17, 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.L.; Marotta, C.A. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: Implications for stroke clinical trials: A literature review and synthesis. Stroke 2007, 38, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muus, I.; Williams, L.S.; Ringsberg, K.C. Validation of the Stroke Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL): Test of reliability and validity of the Danish version (SS-QOL-DK). Clin. Rehabil. 2007, 21, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Safari, A.; Vossoughi, M.; Golbon-Haghighi, F.; Kamali-Sarvestani, M.; Ghaem, H.; Borhani-Haghighi, A. Stroke specific quality of life questionnaire: Test of reliability and validity of the Persian version. Iran. J. Neurol. 2015, 14, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S.G.; Heiberg, G.A.; Nielsen, J.F.; Friborg, O.; Stabel, H.H.; Anke, A.; Arntzen, C. Validity, reliability and Norwegian adaptation of the Stroke-Specific Quality of Life (SS-QOL) scale. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312117752031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakverdioğlu Yönt, G.; Khorshid, L. Turkish version of the Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, M.J. 2—Evidence-Based Practice: The Basic Tools. In Cooper’s Fundamentals of Hand Therapy, 3rd ed.; Wietlisbach, C.M., Ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2020; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Hwang, Y.; Yu, J.; Jung, J.; Woo, H.; Jung, H. The correlation between depression, motivation for rehabilitation, activities of daily living, and quality of life in stroke patients. J. Korean Soc. Occup. Ther. 2009, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, H.J.; Kim, K.J.; Chun, I.A.; Moon, O.K. The relationship between stroke patients’ socio-economic conditions and their quality of life: The 2010 Korean community health survey. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paul, S.L.; Sturm, J.W.; Dewey, H.M.; Donnan, G.A.; Macdonell, R.A.; Thrift, A.G. Long-term outcome in the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study: Predictors of quality of life at 5 years after stroke. Stroke 2005, 36, 2082–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhpoo, K.; Charerntanyarak, L.; Ngamroop, R.; Hadee, N.; Chantachume, W.; Lekbunyasin, O.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Tiamkao, S. Factors related to quality of life of stroke survivors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 21, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Shen, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, A.; Xu, T.; Peng, Y.; Li, Q.; Ju, Z.; Geng, D.; Chen, J.; et al. Education Level and Long-term Mortality, Recurrent Stroke, and Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Ischemic Stroke. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-S. A study on the quality of life, self-efficacy and family support of stroke patients in oriental medicine hospitals. Korean J. Health Educ. Promot. 2003, 20, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, H.; Aijaz, B.; Islam, M.; Aftab, U.; Kumar, S.; Shafqat, S. Drug compliance after stroke and myocardial infarction: A comparative study. Neurol. India 2007, 55, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çevik, C.; Tekir, Ö.; Kaya, A. Stroke patients’ quality of life and compliance with the treatment. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2018, 34, 839. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Méndez, B.; Martín-Silva, I.; Tapias-Vilanova, M.; Moreno-Gallo, Y.; Sanjuan-Menendez, E.; Lorenzo-Tamayo, E.; Ramos-González, M.; Montufo-Rosal, M.; Zuriguel-Pérez, E. Very early mobilization in the stroke unit: Functionality, quality of life and disability at 90 days and 1 year post-stroke. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 49, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, S.M.; Alotaibi, H.M.; Alolyani, A.M.; Abu Dali, F.A.; Alshammari, A.K.; Alhwiesh, A.A.; Gari, D.M.; Khuda, I.; Vallabadoss, C.A. Assessment of the stroke-specific quality-of-life scale in KFHU, Khobar: A prospective cross-sectional study. Neurosciences 2021, 26, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelros, P.; Nydevik, I.; Viitanen, M. Poor outcome after first-ever stroke: Predictors for death, dependency, and recurrent stroke within the first year. Stroke 2003, 34, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Stroke Survivors (n = 172) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or Frequency | SD or % | ||

| Age | 62.67 | 13.38 | |

| Gender | Male Female | 106 66 | 61.6 38.4 |

| BMI * | 26.81 | 3.40 | |

| Area of residence | Beirut Bekaa Mount Lebanon North South | 78 12 40 14 28 | 45.30 7.0 23.30 8.10 16.30 |

| Smoking status | Current smoker Ex-smoker Non-smoker | 62 66 44 | 36.0 38.4 25.6 |

| Alcohol consumption | In the past, not anymore No Yes, currently | 36 122 14 | 20.9 70.9 8.1 |

| Marital status | Divorced Married Single Widowed | 8 122 22 20 | 4.7 70.9 12.8 11.6 |

| Number of children (N = 142) | 1 to 2 3 to 4 More than 4 | 32 64 46 | 22.5 45.1 32.4 |

| Level of education | Illiterate School level University level | 48 80 44 | 27.9 46.5 25.6 |

| Employment | Employed Retired Unemployed | 46 52 74 | 26.7 30.2 43.0 |

| Household income | LBP < 2,000,000 LBP 2,000,000–3,500,000 LBP 3,500,000–5,000,000 LBP 5,000,000–6,500,000 LBP 6,500,000–8,000,000 LBP > 8,000,000 | 40 48 32 22 6 24 | 23.3 27.9 18.6 12.8 3.5 14.0 |

| Living: | Alone With family (nuclear or extended) | 16 156 | 9.3 90.7 |

| IFDFW * score | 39.31 | 19.53 | |

| Variable | Category | Stroke Survivors (n = 172) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or Frequency | SD or % | ||

| Date of stroke diagnosis | Less than 1 year 1 to 5 years More than 5 years | 34 114 24 | 19.8 66.2 14.0 |

| Type of stroke | Hemorrhagic Ischemic | 36 136 | 20.9 79.1 |

| First or recurrent stroke | First Recurrent | 144 28 | 83.7 16.3 |

| Number of comorbidities | 3.80 | 2.44 | |

| Number of medications | 6.23 | 3.10 | |

| LMAS-14 * score | 34.92 | 8.78 | |

| mRS * | Good prognosis Poor prognosis | 40 132 | 23.3 76.7 |

| BI * classes | Slight dependency Moderate dependency Severe dependency Total dependency | 64 28 44 36 | 37.2 16.3 25.6 20.9 |

| Factor | Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toilet use | BI 7 | 0.970 | 0.875 | ||

| Dressing | BI 4 | 0.945 | 0.865 | ||

| Feeding | BI 1 | 0.928 | 0.816 | ||

| Bathing | BI 2 | 0.881 | 0.818 | ||

| Grooming | BI 3 | 0.869 | 0.750 | ||

| Mobility | BI 9 | 0.841 | 0.777 | ||

| My physical condition interfered with my social life | SS-QOL 35 | 0.840 | 0.706 | ||

| I didn’t go out as often as I would like | SS-QOL 31 | 0.837 | 0.691 | ||

| I felt tired most of the time | SS-QOL 1 | 0.817 | 0.642 | ||

| I didn’t join in activities just for fun with my family | SS-QOL 4 | 0.777 | 0.644 | ||

| I was irritable | SS-QOL 23 | 0.724 | 0.431 | ||

| I was discouraged about my future | SS-QOL 18 | 0.697 | 0.493 | ||

| Did you have trouble doing the work you used to do? | SS-QOL 49 | 0.657 | 0.632 | ||

| It was hard for me to concentrate | SS-QOL 36 | 0.599 | 0.553 | ||

| Did you have trouble speaking? For example, get stuck, stutter, stammer, or slur your words? | SS-QOL 7 | 0.440 | 0.487 | ||

| Do you forget taking your medication? | LMAS 13 | 0.830 | 0.690 | ||

| Do you stop taking your medications if they are expensive? | LMAS 14 | 0.823 | 0.666 | ||

| Percentage of variance explained | 44.47% | 15.16% | 8.22% |

| SS-QOL-17 Item Number | Items | r * | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feeding | 0.637 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Bathing | 0.684 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Grooming | 0.620 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Dressing | 0.677 | <0.001 |

| 5 | Toilet use | 0.655 | <0.001 |

| 6 | Mobility | 0.711 | <0.001 |

| 7 | Do you forget taking your medication? | 0.355 | <0.001 |

| 8 | Do you stop taking your medications if they are expensive? | 0.311 | <0.001 |

| 9 | I felt tired most of the time. | 0.714 | <0.001 |

| 10 | I didn’t join in activities just for fun with my family. | 0.749 | <0.001 |

| 11 | Did you have trouble speaking? For example, get stuck, stutter, stammer, or slur your words? | 0.706 | <0.001 |

| 12 | I was discouraged about my future. | 0.599 | <0.001 |

| 13 | I was irritable. | 0.520 | <0.001 |

| 14 | I didn’t go out as often as I would like. | 0.754 | <0.001 |

| 15 | My physical condition interfered with my social life. | 0.761 | <0.001 |

| 16 | It was hard for me to concentrate. | 0.701 | <0.001 |

| 17 | Did you have trouble doing the work you used to do? | 0.771 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Category | Mean | SD | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 40.49 | 12.67 | 0.928 |

| Female | 40.67 | 11.81 | ||

| Marital status | Divorced | 35.25 | 8.43 | 0.612 |

| Married | 41.1 | 12.3 | ||

| Single | 40.27 | 13.19 | ||

| Widowed | 39.7 | 12.94 | ||

| Number of children (N = 142) | 1 to 2 | 38.38 | 11.69 | 0.385 |

| 3 to 4 | 42.09 | 13.24 | ||

| More than 4 | 40.43 | 11.97 | ||

| Level of education | Illiterate | 38.08 | 11.59 | 0.007 a |

| School level | 39.33 | 11.93 | ||

| University level | 45.5 | 12.65 | ||

| Employment | Employed | 45.22 | 12.98 | 0.009 b |

| Unemployed | 38.19 | 10.37 | ||

| Retired | 39.32 | 12.53 | ||

| Household income | LBP < 2,000,000 | 40.1 | 13.72 | 0.001 c |

| LBP 2,000,000–3,500,000 | 38.04 | 9.52 | ||

| LBP 3,500,000–5,000,000 | 39.88 | 11.18 | ||

| LBP 5,000,000–6,500,000 | 36.82 | 10.35 | ||

| LBP 6,500,000–8,000,000 | 42 | 10.32 | ||

| LBP > 8,000,000 | 50.33 | 14.33 | ||

| Medical coverage/insurance | No | 36.64 | 11.99 | <0.001 d |

| Yes, NSSF * | 37.17 | 9.61 | ||

| Yes, private medical insurance or private mutual fund (with or without NSSF *) | 47.9 | 13.14 | ||

| Yes, coverage through the public or military sector (other than NSSF *) | 41.82 | 11.04 | ||

| Living: | Alone | 39.63 | 14.01 | 0.751 |

| With family (nuclear or extended) | 40.65 | 12.17 | ||

| Medications coverage by third-party payers | No | 40.63 | 13.93 | 0.996 |

| Yes, completely | 40.6 | 12.72 | ||

| Yes, partially | 40.46 | 10.17 | ||

| Financial difficulties to obtain medications | No | 42.17 | 12.57 | 0.06 |

| Yes, mild difficulty | 43.96 | 12.44 | ||

| Yes, severe difficulty | 38.85 | 13.36 | ||

| Yes, moderate difficulty | 38.2 | 10.19 | ||

| Obtaining medications from outside the country due to their unavailability in Lebanon | No | 38.15 | 12.41 | 0.088 |

| Yes, sometime | 41.75 | 10.33 | ||

| Yes, always | 42.5 | 7.15 | ||

| Yes, most of the time | 44.91 | 16.89 | ||

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient ** | p Value | ||

| Age | −0.161 | 0.035 | ||

| IFDFW * score | 0.265 | <0.001 | ||

| Number of medications | −0.343 | <0.001 | ||

| LMAS-14 * score | 0.344 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 1 Including Socioeconomic Characteristics * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unstandardized Beta | Standardized Beta | p Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| IFDFW‡ score | 0.093 | 0.142 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.149 |

| Household income (reference: LBP > 8,000,000) LBP <2,000,000 LBP 2,000,000–3,500,000 LBP 3,500,000–5,000,000 LBP 5,000,000–6,500,000 | −4.683 −5.476 −3.903 −2.897 | −0.137 −0.183 −0.118 −0.084 | 0.008 <0.001 0.018 0.088 | −8.132 −8.54 −7.124 −6.225 | −1.234 −2.412 −0.681 0.432 |

| Model 2 Including Sociodemographic Characteristics ** | |||||

| Variable | Unstandardized Beta | Standardized Beta | pValue | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | −0.117 | −0.112 | 0.014 | −0.209 | −0.024 |

| Level of Education (Illiterate vs. University level) | −6.428 | −0.184 | <0.001 | −9.38 | −3.477 |

| Employment (reference: Employed) Unemployed Retired | −6.170 −2.142 | −0.177 −0.083 | <0.001 0.080 | −9.543 −4.542 | −2.797 0.258 |

| Model 3 Including the Therapeutic Characteristics and Significant Variables in Models 1 and 2 *** | |||||

| Variable | Unstandardized Beta | Standardized Beta | pValue | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Number of medications | −1.148 | −0.289 | <0.001 | −1.701 | −0.595 |

| LMAS-14‡score | 0.305 | 0.217 | 0.004 | 0.099 | 0.511 |

| IFDFW‡score | 0.123 | 0.194 | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.213 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakr, F.; Dabbous, M.; Akel, M.; Salameh, P.; Hosseini, H. Construction and Validation of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL-17): A Comprehensive Short Scale to Assess the Functional, Psychosocial, and Therapeutic Factors of QOL among Stroke Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315668

Sakr F, Dabbous M, Akel M, Salameh P, Hosseini H. Construction and Validation of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL-17): A Comprehensive Short Scale to Assess the Functional, Psychosocial, and Therapeutic Factors of QOL among Stroke Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315668

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakr, Fouad, Mariam Dabbous, Marwan Akel, Pascale Salameh, and Hassan Hosseini. 2022. "Construction and Validation of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL-17): A Comprehensive Short Scale to Assess the Functional, Psychosocial, and Therapeutic Factors of QOL among Stroke Survivors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315668

APA StyleSakr, F., Dabbous, M., Akel, M., Salameh, P., & Hosseini, H. (2022). Construction and Validation of the 17-Item Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale (SS-QOL-17): A Comprehensive Short Scale to Assess the Functional, Psychosocial, and Therapeutic Factors of QOL among Stroke Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315668