A Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Australia, Developed during COVID-19

Abstract

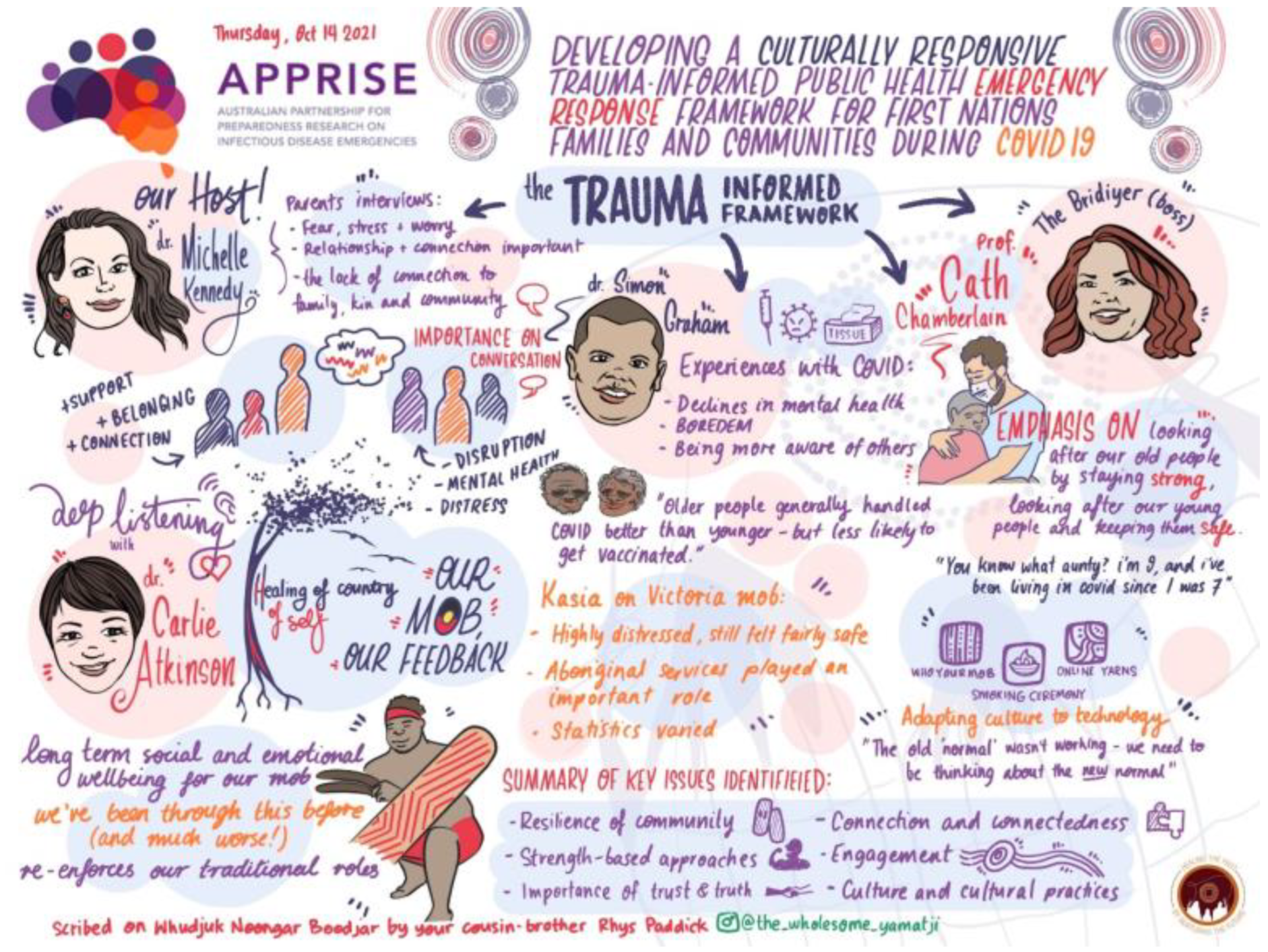

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Study Approach

2.2.1. Rapid Review of Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Frameworks

2.2.2. Interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Parents

2.2.3. A Workshop to Discuss Findings with Key Stakeholders

2.2.4. Workshop Planning to Create a Safe Environment

2.2.5. Workshop Procedure

2.2.6. Workshop Data Analysis

2.3. Ethics

3. Results

- Central goals

- Interdependent core concepts

- Supporting strategies

- Key enablers

- An overarching philosophy

3.1. Level 1: Central Goals

In NSW, many communities went straight from bushfires to COVID; there just wasn’t that time to grieve. Sorry business has been continuous, community still have not overcome the effect of the bushfires.

[It’s] important for young people to be involved in the response and have some control and responsibility. This will also build their resilience.

I think the relationship and the engagement part go really strongly with trust, so if you think about what forms a really strong relationship, trust is usually a key component to that.

[We] need to think about the impacts on adolescents and the impact on their self-esteem. Also, the impacts on the under 5 age group, including parental anxiety and loss of social connections. There needs to be recognition that different age groups are affected in different ways.

3.2. Level 2: Interdependent Core Concepts

The situation would have been less distressing if the hospital staff took the time to listen and understand and respect the family’s needs and wishes. If there was more compassion in their response.

I think one of the biggest challenges that we do have at the moment is with people being a bit hesitant about vaccines and having understandable lack of trust, is how do we keep them connected and not feel othered, …and the importance of having inclusive and not divisive language and ways of talking and way of being in this pandemic and helping everybody come through it together.

What was missing to some extent was discussion around the necessity for positive health messaging, particularly when a lot of the messaging since [the] outbreak has been focused on what people cannot do, which has an impact on self-determination and agency.

3.3. Level 3: Supporting Strategies

We need more on choice/the right for choice—important aspect of cultural integrity. Perhaps belongs between communication and equity and human rights.

3.4. Level 4: Key Enablers

It is important to capture the role of Elders in supporting the younger generation and also the role that the younger generation has in supporting Elders.

3.5. Level 5: Overarching Philosophy

3.6. Elements which Weave through Each Layer

3.6.1. Time—Past, Present and Future

3.6.2. Trauma—Individual, Collective and Historical

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Implications for Policy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, S.; Blaxland, M.; Bolt, R.; Beadman, M.; Gardner, K.; Martin, K.; Doyle, M.; Beetson, K.; Murphy, D.; Bell, S.; et al. Aboriginal peoples’ perspectives about COVID-19 vaccines and motivations to seek vaccination: A qualitative study. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyammahi, S.K.; Abdin, S.M.; Alhamad, D.W.; Elgendy, S.M.; Altell, A.T.; Omar, H.A. The dynamic association between COVID-19 and chronic disorders: An updated insight into prevalence, mechanisms and therapeutic modalities. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 87, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW. Australia’s Welfare 2021 Data Insights. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/ef5c05ee-1e4a-4b72-a2cd-184c2ea5516e/aihw-aus-236.pdf.aspx (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Cloitre, M.; Stolbach, B.C.; Herman, J.L.; van der Kolk, B.; Pynoos, R.; Wang, J.; Petkova, E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, J.L. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1992, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (Ed.) International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M.; Garvert, D.W.; Brewin, C.R.; Bryant, R.A.; Maercker, A. Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2013, 4, 20706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kezelman, C.; Stavropoulos, P. ‘The Last Frontier’–Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Complex Trauma and Trauma Informed Care and Service Delivery. 2012. Available online: https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/IND.0521.001.0001.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Bridgland, V.M.E.; Moeck, E.K.; Green, D.M.; Swain, T.L.; Nayda, D.M.; Matson, L.A.; Hutchison, N.P.; Takarangi, M.K.T. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0240146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiri, D.; Moccia, L.; Dattoli, L.; Pepe, M.; Molinaro, M.; De Martin, V.; Chieffo, D.; Di Nicola, M.; Fiorillo, A.; Janiri, L.; et al. Emotional dysregulation mediates the impact of childhood trauma on psychological distress: First Italian data during the early phase of COVID-19 outbreak. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 55, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.; Lahav, Y. Emotion regulation and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of childhood abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, L.M.D.; Millman, Z.B.; Öngür, D.; Shinn, A.K. The intersection between childhood trauma, the COVID-19 pandemic, and trauma-related and psychotic symptoms in people with psychotic disorders. Schizophr. Bull. Open 2021, 2, sgab050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, G.; Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Fernández, M.E. Finding theory- and evidence-based alternatives to fear appeals: Intervention Mapping. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speight, J. Why the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Fear Appeal to Sydney Residents Won’t Work. The Conversation 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-the-federal-governments-covid-19-fear-appeal-to-sydney-residents-wont-work-164317 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Tannenbaum, M.B.; Hepler, J.; Zimmerman, R.S.; Saul, L.; Jacobs, S.; Wilson, K.; Albarracín, D. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, V.; Knauft, K.; Hayatbini, N. Cognitive flexibility and perceived threat from COVID-19 mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and state anxiety. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, B. The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kulk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and the Body in the Healing of Trauma; Penguin Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, P.; Minton, K.; Pain, C. Trauma and the Body: A Sensory Motor Approach to Psychotherapy; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, R.M.; Ronald, M.; Tonkinson, R. Australian Aboriginal Peoples; Encyclopedia Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Australian-Aboriginal (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Thurber, K.A.; Barrett, E.M.; Agostino, J.; Chamberlain, C.; Ward, J.; Wade, V.; Belfrage, M.; Maddox, R.; Peiris, D.; Walker, J.; et al. Risk of severe illness from COVID-19 among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults: The construct of ‘vulnerable populations’ obscures the root causes of health inequities. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2021, 45, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. Trauma Trails, Recreating Song Lines: The Transgenerational Effects of Trauma in Indigenous Australia; Spinifex Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies, K. Understanding the Australian Aboriginal experience of collective, historical and intergenerational trauma. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.; Casey, D.; Ward, J.S. First Nations people leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, D.; Mellor, D. Reconciliation between Aboriginal and Other Australians: The “Stolen Generations”. J. Soc. Issues 2006, 62, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunneen, C.; Libesman, T. Postcolonial trauma: The contemporary removal of Indigenous children and young people from their families in Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 35, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwick, A.; Ansari, Z.; Clinch, D.; McNeil, J. Experiences of racism among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults living in the Australian state of Victoria: A cross-sectional population-based study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairuz, C.A.; Casanelia, L.M.; Bennett-Brook, K.; Coombes, J.; Yadav, U.N. Impact of racism and discrimination on physical and mental health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples living in Australia: A systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P. Violence against Aboriginal women in Australia: Possibilities for redress within the international human rights framework. Albany Law Rev. 1996, 60, 917–941. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Cultural Safety in Health Care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring Framework. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/cultural-safety-health-care-framework/contents/summary (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Haokip, T. IV: Glimpses from villages in the Northeast: Traditional quarantine measures came alive during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contrib. Indian Sociol. 2022, 56, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.; Taylor, K.; Law, C.; Campbell, S.; Miller, A. Engage, understand, listen and act: Evaluation of Community Panels to privilege First Nations voices in pandemic planning and response in Australia. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, S.M.; Davis, J.S.; Su, J.; Oliver-Landry, E.P.; Rogers, B.A.; Goldstein, A.; Thomas, J.H.; Parameswaran, U.; Bigham, C.; Freeman, K.; et al. Disproportionate impact of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza on Indigenous people in the Top End of Australia’s Northern Territory. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lowitja Institute. Closing the Gap Report: We Nurture Our Culture for the Future, and Our Culture Nurtures Us; The Lowtija Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, V.; Adams, J.; Champion, D.; Hogarth, G.; Mahony, A.; Monck, R.; Pinnegar, T.; dos Santos, N.S.; Watson, C. The role of Aboriginal leadership in community health programmes. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durey, A.; McEvoy, S.; Swift-Otero, V.; Taylor, K.; Katzenellenbogen, J.; Bessarab, D. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: Beyond education and training of practitioners. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2014, 38, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durey, A.; McEvoy, S.; Swift-Otero, V.; Taylor, K.; Katzenellenbogen, J.; Bessarab, D. Improving healthcare for Aboriginal Australians through effective engagement between community and health services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Gee, G.; Brown, S.J.; Atkinson, J.; Herrman, H.; Gartland, D.; Glover, K.; Clark, Y.; Campbell, S.; Mensah, F.K.; et al. Healing the past by nurturing the future—Co-designing perinatal strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander parents experiencing complex trauma: Framework and protocol for a community-based participatory action research study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L.M.; Jacquez, F. Participatory Research Methods—Choice Points in the Research Process. J. Particip. Res. Methods 2020, 1, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heris, C.; Kennedy, M.; Graham, S.; Bennetts, K.S.; Atkinson, C.; Mohamed, J.; Woods, C.; Chennall, R.; Chamberlain, C. Key features of a trauma-informed public health emergency approach: A rapid review. Front. Public Health 2022, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heris, C.; Chamberlain, C.; Woods, C.; Herrman, H.; Mohamed, J.; Kennedy, M.; Bennetts, S.K.; Graham, S. 10 Ways We Can Better Respond to the Pandemic in a Trauma-Informed Way. The Conversation 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/10-ways-we-can-better-respond-to-the-pandemic-in-a-trauma-informed-way-168486 (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Y.; Gee, G.; Ralph, N.; Atkinson, C.; Brown, S.; Glover, K.; McLachlan, H.; Gartland, D.; Hirvoven, T.; Andrews, S.; et al. The healing the past by nurturing the future: Cultural and emotional safety framework. J. Indig. Wellbeing 2020, 5, 38–57. [Google Scholar]

- The Healing Foundation. Who Are the Stolen Generations? Available online: https://healingfoundation.org.au/resources/who-are-the-stolen-generations/ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- QSR International. NVivo. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. Available online: http://biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/117 (accessed on 2 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Update—23 September 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-update-23-september-2022 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Akem Dimala, C.; Kadia, B.M.; Nguyen, H.; Donato, A. Community and Provider Acceptability of the COVID-19 Vaccine: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Adv. Clin. Med. Res. Healthc. Deliv. 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, J.; Laycock, A.F.; Conte, K.P.; Matthews, V.; Peiris, D.; Bailie, R.S.; Abimbola, S.; Passey, M.E.; Cunningham, F.C.; Harkin, K.; et al. Principles guiding ethical research in a collaboration to strengthen Indigenous primary healthcare in Australia: Learning from experience. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e003852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfield, S.; Davy, C.; Dawson, A.; Mulholland, E.; Braunack-Mayer, A.; Brown, A. Building Indigenous health workforce capacity and capability through leadership–the Miwatj health leadership model. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Buergelt, P.T.; Paton, D.; Smith, J.A.; Maypilama, E.L.; Yuŋgirrŋa, D.; Dhamarrandji, S.; Gundjarranbuy, R. Facilitating sustainable disaster risk reduction in Indigenous communities: Reviving Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and practices through two-way partnering. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, E.A.; Murshid, N.S. Trauma-informed social policy: A conceptual framework for policy analysis and advocacy. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Généreux, M.; Lafontaine, M.; Eykelbosh, A. From science to policy and practice: A critical assessment of knowledge management before, during, and after environmental public health disasters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, C.S.; Pfefferbaum, B. Mental health response to community disasters: A systematic review. JAMA 2013, 310, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, R.J. Trauma and public mental health: A focused review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, B.; Epstein, K.; Dauria, E.F.; Dolce, L. Implementing a trauma-informed public health system in San Francisco, California. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, O.L.; Perry, C.; Azur, M.; Taylor, H.G.; Gwon, H.; Mosley, A.S.; Semon, N.; Links, J.M. Guided preparedness planning with lay communities: Enhancing capacity of rural emergency response through a systems-based partnership. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2013, 28, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C. In the Eye of the Storm: Community-Led Indigenous Informed Responses during a Natural Disaster. Available online: https://mspgh.unimelb.edu.au/centres-institutes/centre-for-health-equity/research-group/indigenous-health-equity-unit/research/apprise-grant/activities/northern-rivers-community-healing-hub (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Fulloon, S. The Indigenous Trauma Specialists Working to Ease a Growing Mental Health Crisis in Flood-Affected NSW. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/small-business-secrets/article/the-indigenous-trauma-counsellors-working-to-prevent-a-mental-health-crisis-in-flood-affected-nsw/c5map6g1f (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Australian Associated Press. Australia’s COVID Lockdown Rules Found to Have Lacked Fairness and Compassion. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/oct/20/australia-covid-lockdown-rules-restrictions-lacked-fairness-compassion-school-closures-unnecessary-report (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Graham, S.; Stelkia, K.; Wieman, C.; Adams, E. Mental health interventions for First Nations, Inuit, and Metis Peoples in Canada: A systematic review. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Graham, S.; Kamitsis, I.; Kennedy, M.; Heris, C.; Bright, T.; Bennetts, S.K.; Jones, K.A.; Fiolet, R.; Mohamed, J.; Atkinson, C.; et al. A Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Australia, Developed during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315626

Graham S, Kamitsis I, Kennedy M, Heris C, Bright T, Bennetts SK, Jones KA, Fiolet R, Mohamed J, Atkinson C, et al. A Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Australia, Developed during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315626

Chicago/Turabian StyleGraham, Simon, Ilias Kamitsis, Michelle Kennedy, Christina Heris, Tess Bright, Shannon K. Bennetts, Kimberley A Jones, Renee Fiolet, Janine Mohamed, Caroline Atkinson, and et al. 2022. "A Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Australia, Developed during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315626

APA StyleGraham, S., Kamitsis, I., Kennedy, M., Heris, C., Bright, T., Bennetts, S. K., Jones, K. A., Fiolet, R., Mohamed, J., Atkinson, C., & Chamberlain, C. (2022). A Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Public Health Emergency Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities in Australia, Developed during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315626