The Effect of Collectivism on Mental Health during COVID-19: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

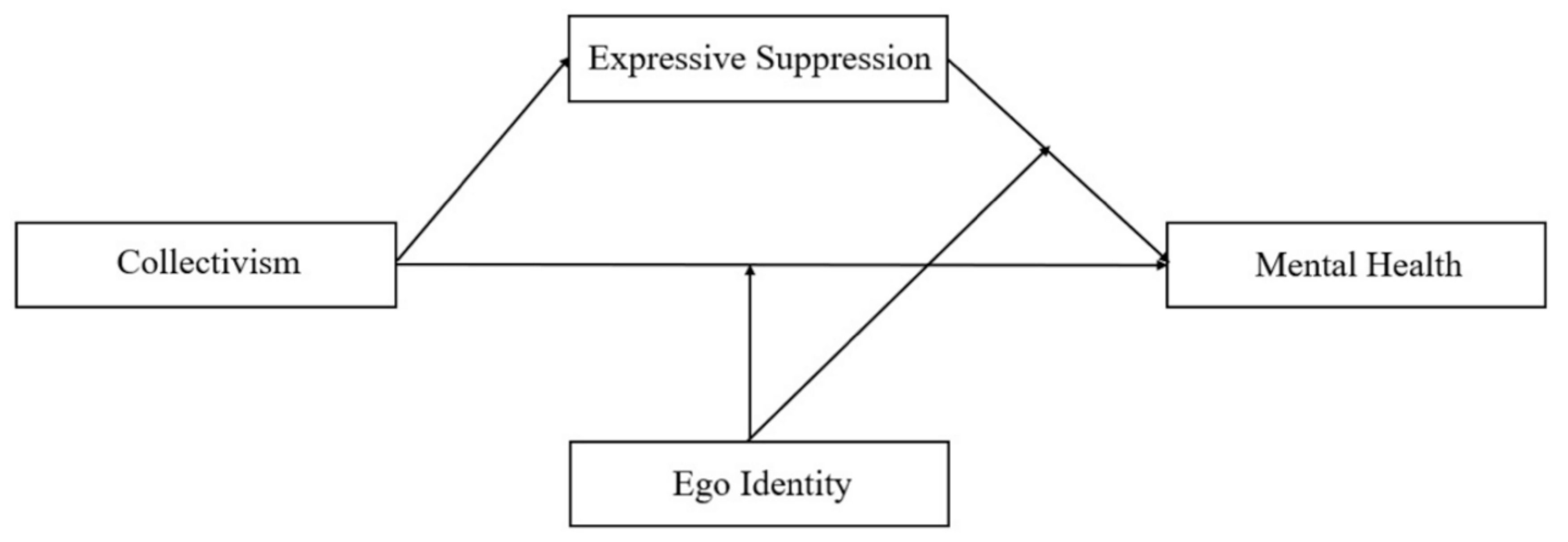

1.1. The Impact of Cultural Differences on Mental Health

1.2. The Mediating Role of Expressive Suppression

1.3. The Moderating Role of Ego Identity

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Mental Health during COVID-19

2.2.2. Collectivism Tendency

2.2.3. Gross Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

2.2.4. The Identity Status Scale (ISS)

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Biases

3.2. Description and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Test of Moderated Mediation

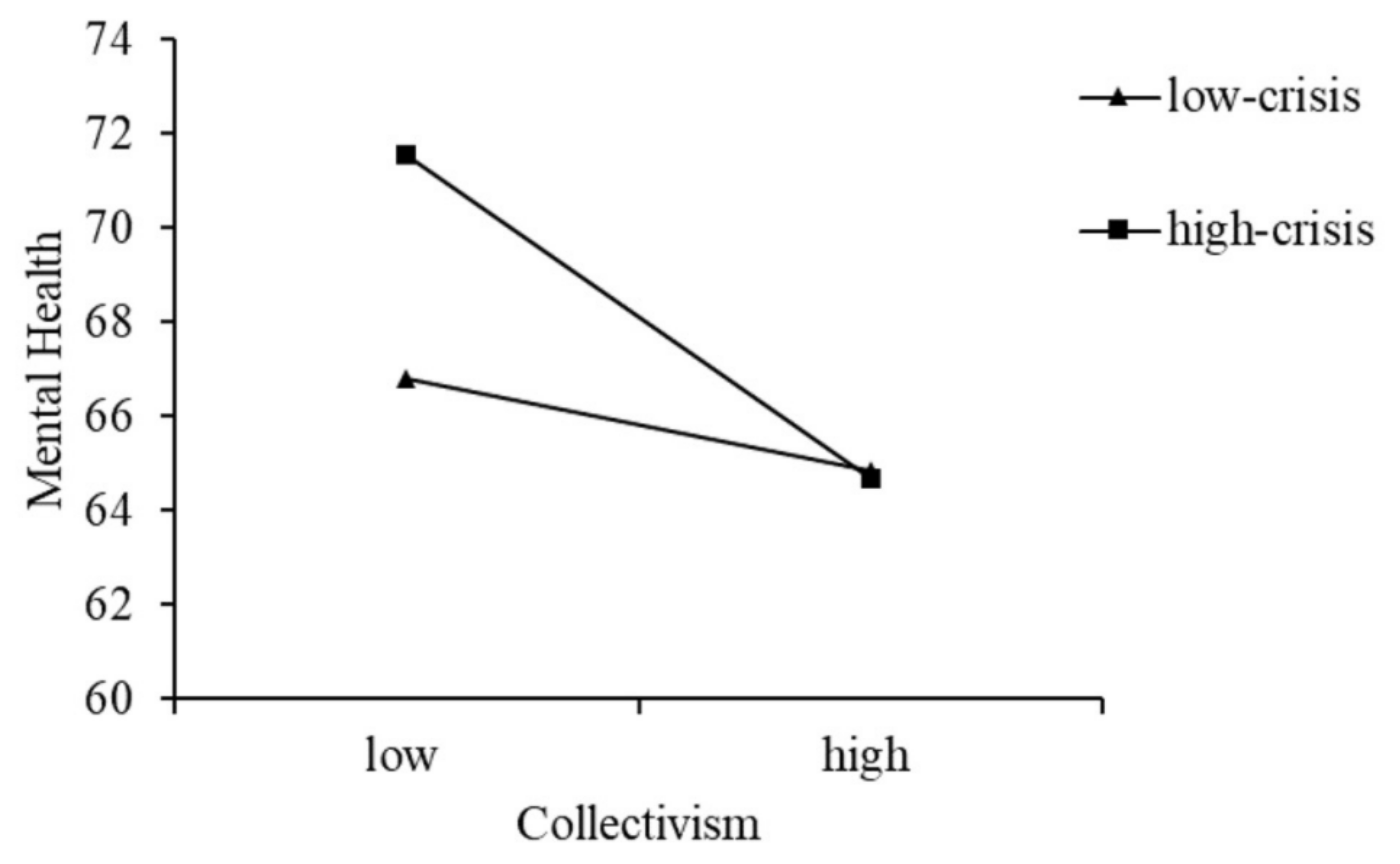

3.3.1. Crisis as a Moderating Variable

3.3.2. Commitment as a Moderating Variable

3.3.3. Exploration as a Moderating Variable

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Expressive Suppression

4.2. The Moderating Role of Ego Identity between Expressive Suppression and Mental Health

4.3. The Moderating Role of Ego Identity between Collectivism and Mental Health

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. World Health Organization Declares COVID-19 a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”: Travel and Trade Restrictions against China Not Recommended. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/gjhzs/s7952/202001/b196e4f678bc4447a0e4440f92dac81b.shtml (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Meng, X.H.; Li, Q.; Tu, Y.B.; Zhou, Y.B. A Qualitative research on the psychological aspects of facing death during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 44, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Research Group on Public Awareness and Individual Preventive Behavior of the COVID-19. COVID-19 Awareness Survey Report|More Than 70% of Respondents Give Full Marks to Frontline Medical Personnel. Available online: https://news.sina.com.cn/o/2020-01-29/doc-iihnzhha5208367.shtml (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Otu, A.; Charles, C.H.; Yaya, S. Mental health and psychosocial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Invisible Elephant in the room. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.H.; Chen, H.P.; Hu, W.W.; Li, J.W.; Zeng, M.; Ren, X.; Yang, J. Cultural values affect the perceived stress in general health public in China COVID-19. China J. Heath Psychol. 2021, 29, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Brougham, D.; Haar, J. Individualism and collectivism: Evidence of compatibility in Iran and the United States. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 114, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, N.; Bing, M.N.; Watson, P.; Kristl Davison, H.; LeBreton, D.L. Individualist and collectivist values: Evidence of compatibility in Iran and the United States. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knyazev, G.G.; Kuznetsova, V.B.; Savostyanov, A.N.; Dorosheva, E.A. Does collectivism act as a protective factor for depression in Russia? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 108, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, R.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Hong, W.; Wu, Y. The influence of communication on college students’ self–other risk perceptions of COVID-19: A comparative study of china and the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.C.; Oyserman, D. Seeing meaning even when none may exist: Collectivism increases belief in empty claims. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 122, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloitre, M.; Khan, C.; Mackintosh, M.A.; Garvert, D.W.; Henn-Haase, C.M.; Falvey, E.C.; Saito, J. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ACES and physical and mental health. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopp, H.; Troy, A.S.; Mauss, I.B. The unconscious pursuit of emotion regulation: Implications for psychological health. Cogn. Emot. 2011, 25, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.A.; Perez, C.R.; Kim, Y.; Lee, E.A.; Minnick, M.R. Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion 2011, 11, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, K.; Nie, Y.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.B. Adolescent’s regulatory emotional self-efficacy and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of regulatory emotional style. J. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 36, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, D.F. Usage of emotion suppression and its relationship with mental health. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 1, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, E.A.; Lee, T.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion 2007, 7, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. Are cultural differences in emotion regulation mediated by personality traits? J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2006, 37, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.A.; Egloff, B.; Wlhelm, F.H.; Smith, N.C.; Erickson, E.A.; Gross, J.J. The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion 2003, 3, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Liu, K.Y.; Li, T.T.; Lu, L. The impact of mindfulness on subjective well-being of college students: The mediating effects of emotion regulation and resilience. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Li, H.H.; Zhou, K.; Xu, R.H.; Fu, Y.X. Social adjustment and emotion regulation in college students with depression-trait. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 799–803. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, R. A Study on the Influence Mechanism of Ego-Identity of Junior High School Students—Based on the Analysis of Individual Level and Peer Group Level. Master’s Thesis, Wenzhou University, Wenzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A. A study of identity statuses and their structure in university students. Japn. J. Educ. Psychol. 1983, 31, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shirai, T.; Nakamura, T.; Katsuma, K. Identity development in relation to time beliefs in emerging adulthood: A long-term longitudinal study. Identity 2016, 16, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Ego-Identity and Mental Health of College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Ego Identity Development in Adolescence—Research on Identity Status and Its Related Factors. Master’s Thesis, He Bei University, Baoding, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, D.Y. Relationship between existential anxiety and depression: Self-identity’s double effects. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 3, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Cui, Y.; Pang, Y.J. The correlative research between ego identity and mental health and personality of college students. J. Educ. Instit. Jilin Prov. 2014, 9, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. Research on the Mental Health Measurement and Current Situation of People under the COVID-19. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hooft, E.A.; Jong, M. Predicting job seeking for temporary employment using the theory of planned behaviour: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, H.C.; Li, Z.Q.; Du, W. Reliability and validity of emotion regulation questionnaire Chinese revised version. China J. Heath Psychol. 2007, 1, 503–505. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, F.; Schulz, P. Multiple correlations and bonferroni’s correction. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 44, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramzan, N.; Amjad, N. Cross cultural variation in emotion regulation: A systematic review. Ann. King Edw. Med. Univ. 2017, 23, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Tang, G.; Huang, M. Expressive suppression, confucian Zhong Yong thinking, and psychosocial adjustment among Chinese young adults. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 25, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, D.J.; Lei, C.X. Anxiety regulation: Comparing the strategy of acceptance to expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Psychol. Exp. 2011, 31, 372–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J. Discussions on Ego Identity; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Dufour, G.; Sun, Z.; Galante, J.; Xing, C.; Zhan, J.; Wu, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of young people: A comparison between China and the United Kingdom. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/table/ (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K.; Updegraff, J.A. Fear of ebola. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Güler, A. Positivity explains how covid-19 perceived risk increases death distress and reduces happiness. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyckx, K.; Soenens, B.; Berzonsky, M.D.; Smits, I.; Goossens, L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Information-oriented identity processing, identity consolidation, and well-being: The moderating role of autonomy, self-reflection, and self-rumination. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.63 | 0.48 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Age | 21.25 | 6.58 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Mental health (revised) | 66.88 | 13.01 | −0.18 * | −0.07 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Fear (revised) | 22.84 | 6.06 | −0.27 *** | −0.04 | 0.91 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| Depression (revised) | 20.49 | 3.125 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.58 *** | 0.45 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Anxiety (revised) | 14.02 | 4.47 | −0.05 | −0.14 | 0.79 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.19 ** | 1 | |||||||

| Anger (revised) | 9.52 | 2.9 | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.76 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.55 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Crisis | 14.25 | 2.17 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 1 | |||||

| Commitment | 14.55 | 2.98 | −0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.38 *** | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.31 *** | 1 | ||||

| Exploration | 13.68 | 1.68 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.30 *** | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.32 *** | 0.53 *** | 1 | |||

| Collectivism | 33.25 | 4.68 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.20 ** | −0.13 | 0.02 | −0.28 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.01 | 0.21 *** | 0.18 ** | 1 | ||

| Cognitive reappraisal | 26.06 | 3.98 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.16 | −0.14 | −0.14 | 0.22 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.45 *** | 1 | |

| Expressive suppression | 13.62 | 3.56 | −0.20 ** | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.02 | −0.15 | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.22 *** | 0.24 *** | 1 |

| Variable | Outcome Variable: Expressive Suppression | Outcome Variable: Mental Health | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | se | t | LLCI | ULCI | β | se | t | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Age | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.432 | −0.038 | 0.059 | −0.094 | 0.090 | −1.045 | −0.272 | 0.083 |

| Collectivism | 0.169 | 0.035 | 4.848 *** | 0.100 | 0.237 | 1.256 | 0.818 | 1.535 | −0.352 | 2.863 |

| Expressive suppression | −3.418 | 1.145 | −2.986 ** | −5.668 | −1.168 | |||||

| Crisis | 1.602 | 1.870 | 0.857 | −2.074 | 5.277 | |||||

| Interaction 1 | −0.121 | 0.057 | −2.137 * | −0.233 | −0.010 | |||||

| Interaction 2 | 0.217 | 0.078 | 2.774 ** | 0.063 | 0.371 | |||||

| R2 | 0.050 | 0.077 | ||||||||

| F | 12.074 *** | 6.262 *** | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Yao, W.; Guo, Y.; Liao, Z. The Effect of Collectivism on Mental Health during COVID-19: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315570

Gao Y, Yao W, Guo Y, Liao Z. The Effect of Collectivism on Mental Health during COVID-19: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315570

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yixuan, Wenjie Yao, Yi Guo, and Zongqing Liao. 2022. "The Effect of Collectivism on Mental Health during COVID-19: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315570

APA StyleGao, Y., Yao, W., Guo, Y., & Liao, Z. (2022). The Effect of Collectivism on Mental Health during COVID-19: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315570