Families, Parenting and Aggressive Preschoolers: A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Family Variables Related to Preschool Aggression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.1.1. Stage 1: Research Question

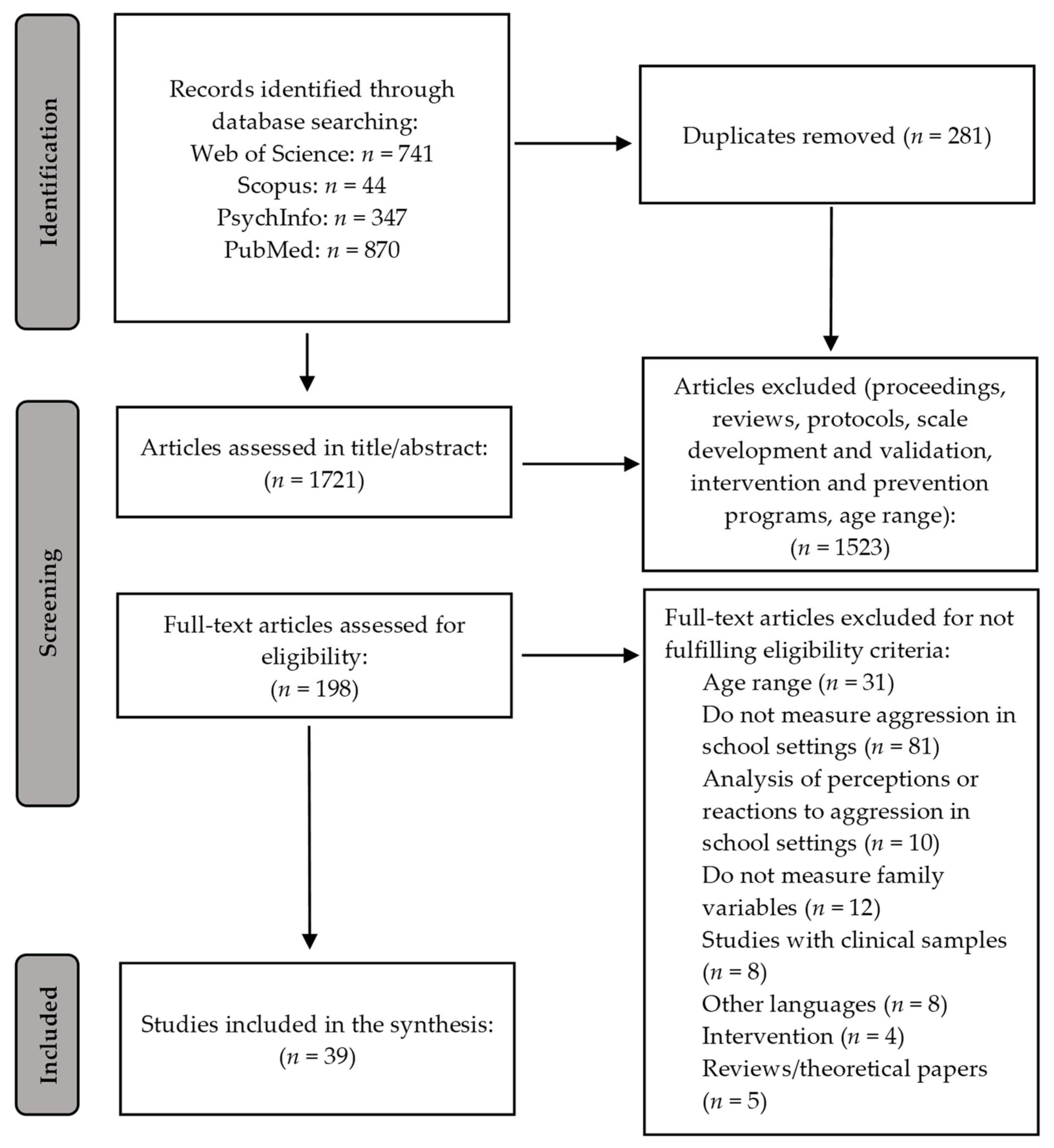

2.1.2. Stage 2: Identification of Studies

2.1.3. Stage 3: Study Selection

2.1.4. Stage 4. Charting and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Methodological Differences

3.3. Family Variables Included in the Studies

3.4. Primary Analysis

3.4.1. Sociodemographic Variables

Number of Siblings

Family Structure

Socioeconomic Level

Level of Educational Attainment

Parental Occupation

Unemployment

3.4.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences

Exposure to Violence

Parent–Child Conflict

Physical Abuse

Parental Criminality

Psychopathology

Chronic Disease within the Family

Death of a Family Member

Problems during Pregnancy

History of Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy

Family Stress

3.4.3. Parenting Practices

Parental Styles

Physical Coercion

Psychological Control

Neglect/Rejection

Warmth and Affection

Attachment

Parenting Self-Efficacy

Parental Values (Individualism, Collectivism and Verticalism)

Social Coaching Qualities (Elaboration, Emotion References and Rule Violation)

Other Emotional Variables

3.4.4. Other Factors

Daily Working Hours and Days of Work

Time Spent with the Child

4. Discussion

Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors (Year) Country | Sample and Main Characteristics | Aim of the Study | Study Design and Methodology Approach | Types of Preschool Aggression Examined | Preschool Aggression Assessment Tools | Family Variables Included | Statistical Analyses Included to Test the Association between Preschool Aggression and Family Variables | Key Findings about the Relationship between Preschool Aggression and Family Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeMulder, Denham, Schmidt and Mitchell [84]. United States. | 94 children and their mothers Children’s sex: 51 boys, 43 girls Age range: 38–58 months Ethnicity: 81% White | Investigate the relationships between preschoolers’ secure-base behavior at home, stressful family conditions and relationships with peers and teachers in preschool. | Cross-sectional | Anger/Aggression (perpetration) | “Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation”- Teacher reports (SCBE-30; LaFreniere and Dumas, 1996). | Security with mother, assessed through observations at home (AQS, Waters et al., 1994). Family stress, self-reported by mothers through the “Life Experiences Survey” (LES, Sarason et al., 1978). | Bivariate and multivariate analysis | Boys and girls less securely attached to their mothers expressed more anger/aggression in preschool. Higher levels of family stress were only significantly related to anger/aggression for boys. |

| Honig and Su [67]. Taiwan. | 90 children: 30 in mother’s custody, 30 in father’s custody, and 30 from two-parent families Children’s sex: 50% girls Mean age reported = 5.39 (SD = 1.00) Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the effects of divorce and custody arrangements on preschool children’s emotional adjustment. | Cross-sectional | Hostile, aggressive behavior(perpetration) | “Preschool Behavior Questionnaire”-Teacher reports (PBQ; Behar and Stringfield, 1974). | Effect of divorce and custody arrangements assessed through open-ended interviews with parents. | Bivariate and multivariate analysis | No significant differences were found between children from married families in comparison with children living in divorced families. Boys are more aggressive than females, regardless of family configuration. Children who were in custody with same-sex parents had significantly lower aggression scores. |

| Farver, Xu, Eppe, Fernandez and Schwartz [77]. United States. | 431 children, their mothers and their teachers Children’s sex: 50% girls Age range: 43–59 months Ethnicity: 85% African American; 15% Latino | Analyze relations among family conflict, community violence, mothers depressive symptoms and children’s socioemotional functioning. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression, including physical, verbal, relational and bullying (perpetration) | “Social Behavior Rating Scale”-Teacher reports (SBRS, Schwartz, 2000). | Family conflict, assessed through mothers’ scores on the Conflict Tactics Scale (Strauss, 1979). Mothers’ depressive symptoms, assessed through scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1996). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis Mediational path analysis: Mothers’ depressive symptoms y children’s social awareness were tested as mediators | Mothers’ reports of family conflict were not correlated with teachers’ ratings of aggressive behaviors. |

| Ngee Sim and Ping Ong [80]. Singapore. | 286 children, their parents and 35 teachers Children’s sex: 50% girls Age range: 4–6 years old Ethnicity: 100% Singapore Chinese | Examine the relationships between two forms physical punishment (caning and slapping) and child aggression, testing for moderation by authoritative control and rejection. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression, including physical, verbal, relational and bullying (perpetration) | Teacher reports of child aggression through items adapted and expanded from Dodge and Coie (1987). | Physical punishment and trough parents’ reports using the ”Conflict Tactics Scale” (Strauss, 1990). Authoritative control assessed through mothers’ and fathers’ reports using the Parental Authority Questionnaire (Buri, 1991). Perceived parental rejection through structured interviews with children using items from the “Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire” (Rohner, 1990). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis Moderation analyses conducted Authoritative control and perceived parental rejection were tested as moderators | Relations were found between each punishment type and aggression depending on the specific parent–child dyad. Father caning is related to aggression, regardless of child gender, whereas mother caning is related to child aggression only at low children’s perceived rejection. Mother slapping is related to sons’ aggression, whereas father slapping is related to daughters’ aggression only at low children’s’ perceived rejection values. Authoritative control did not play a moderate role. |

| Casas et al. [86]. United States. | 122 children and their parents (119 mothers and 85 fathers) Children’s sex: 57% girls Age range: 2 years and 6 months old to 5 years and 10 months old Ethnicity: 87% Anglo American | Analyse how children’s use of relational and physical aggression varies according to parent–child relationships. | Cross-sectional | Physical and relational aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). Parents’ reports through the “Children’s Social Experiences measure” (CSE, Crick, Casas et al., 1999). | Parental reports of parental styles using the “Parenting Practices Questionnaire” (PPQ, Robinson et al., 2001), psychological control using the “Psychological Control Measure (Olsen et al., 2022), attachment styles using the “Parent/Child Reunion Inventory (Marcus, 1991). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Authoritarian and permissive parenting styles were positively related to children’s relational aggression. Authoritative parenting style was associated with less children’s physical aggression. Parental psychological control was related with relational and physical aggression. Insecure attachment was associated with relational and physical aggression. Associations varies according to the sex composition of the parent–child dyad. |

| Nelson et al. [89]. China. | 215 children and their parents (180 mothers and 167 fathers) Children’s sex: 53% girls Age range: 46–76 months Ethnicity: not reported | Assess the combined and differential contributions of spouse reported parenting styles in physical and relational aggression. | Cross-sectional | Physical and relational aggression (perpetration) | Peer nomination procedure through the adaptation of the items from Crick, Casas and Mosher (1997). | Negative parenting (coercion and psychological control) assessed through parent’s reports of their partners practices using items adapted from previous measures (Robinson et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2004). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Combined parenting effects were more prevalent than differential effects in predicting aggression. Physical coercion was predictive of relational and physical aggression in boys, and psychological control was primarily associated with physical and relational aggression in girls. |

| Ostrov, Crick and Stauffacher [11]. United States. | 50 children (25 sibling dyads, 13 same-sex and 11 mixed-sex pairs) Children’s sex: 48% girls Age range: 27–61 months Ethnicity: 72% Europena American | Examine the relationship between the sibling relationship and school-based peer aggression. | Short-term longitudinal | Physical and relational aggression (perpetration) | Naturalistic observations in classrooms at two different points (fall and spring). | Sibling physical and relational aggressive behavior through naturalistic observations in classrooms. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Older sibling’s relational and physical aggression predicted younger sibling’s relational and physical aggression with peers. |

| Ostrov and Bishop [76]. United States. | 47 children and their parents (43 mothers and 4 fathers) Children’s sex: 63% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 43.54 months (SD = 8.02) Ethnicity: 63.8% Caucasian | Investigate the relationships between parent–child relationships qualities and physical and relational aggression with peers at school. | Cross-sectional | Physical and relational aggression (perpetration) | Naturalistic observations in classrooms. Teachers’ reports through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). Parents’ reports through the “Children’s Social Behavior” scale (CSB, Crick, 2006a). | Parent–child conflict and child’s use of physical aggression toward the parent, assessed through parent’s reports using the “Parent Qualities Measure (PQM, Crick, 2006b). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Parent–child conflict was associated with relational aggression, even when controlling for physical aggression and gender. |

| Shin and Kim [90]. South Korea. | 297 children, their parents, and teachers (data about number of parents and teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 44.1% girls Age range: 4–5 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Examine relationships between child characteristics (aggression and withdrawal), parenting behaviors, teacher–child relationships and peer victimization. | Cross-sectional | Relational and physical victimization Aggression and withdrawal (child characteristics) | Teachers’ reports about peer victimization based on previous studies (Schwartz et al., 2002). Teachers’ reports about aggression and withdrawal through the “Social Competence and Behaviour Evaluation” scale (SCBE, LaFreniere and Dumas, 1996). | Parenting behaviours (warmth, neglect/rejection, physical coercion), assessed through parents’ report on an adapted measure (Kim and Park, 2006). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Parental neglect/rejection increased the probability of being victimised by peers. Children who were characterised by withdrawal or aggressive behaviour were likely to be victimised by peers. |

| Amin, Behalik and El Soreety [72]. Egypt. | 50 children and their mothers Children’s sex: 50% girls Age range: 3–6 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Analyze the prevalence and factors associated with aggression in preschool settings. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression, including physical, verbal, and relational forms (perpetration) | Naturalistic observations in classrooms. | Mothers’ education and occupation (method of assessment not reported). | Bivariate analyses | Aggressive scores were lower among children whose mothers had university education. However, aggressive scores were higher among children whose mothers work out of home. |

| Buyse, Verschueren and Doumen [93]. Belgium. | 127 children, their mothers, and teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 50.3% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 4.11 years old (SD = 4) Ethnicity: not reported | Evaluate the moderating role of teacher–child closeness for the association between mother-child attachment quality. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the aggressive behavior subscale of the “Child Behavior Scale” (CBS, Ladd and Profilet, 1996). | Mother-child attachment assessed through a semi-structured observation in the home environment. | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis Moderation analyses conducted Teacher–Child Closeness was tested as moderator | Children with lower quality attachment to their mother showed higher scores of aggressive behaviours. Teacher–child closeness moderates the relationships between lower quality of attachment and aggressive behaviour. |

| Olson et al. [79]. United States. | 199 children, their mothers, and teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 59.2% girls Age range = 32–45 months Ethnicity: 91% European American heritage | Identify preschool-age self-regulatory, social-cognitive and parenting precursors of children’s peer aggression following the transition to school. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression, including physical, verbal, and object aggression forms (perpetration) | Naturalistic observations in classrooms at two different points (at age 3 and 6 years). Teachers ratings at 3 years using the “Caregiver/Teacher Report Form” (Achenbach, 1997). Teacher ratings at 6 years using the “Inventory of Peer Relations” (Dodge and Coie, 1987). | Parenting risk (corporal punishment and low warmth/responsiveness) assessed using interview-based and questionnaire (Parenting Dimensions Inventory; Power, 1993). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Interaction analyses conducted between the study variables | Children showing high levels of aggressive peer interaction in school also showed higher levels of adverse parenting than others did. Early corporal punishment was associated with higher peer aggression across the transition from preschool to school. Regarding interaction, low warm responsiveness was the best precursors of later peer aggression in children with low levels of theory of mind. |

| Jansen et al. [68]. Netherlands. | 6376 children, their parents, and teachers (number mother, parents and teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 49% girls Age range = 5–6 years old Ethnicity: 57% Dutch | Examine the prevalence and socioeconomic disparities in bullying behaviour among young elementary school children. | Cross-sectional | Bullying, including physical, verbal, relational and material forms (perpetration and victimization) | Teachers reports of bullying by means of questionnaires (Perren and Alsaker, 2006). | Family socioeconomic status assessed by a parental report in an ad hoc questionnaire. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families had a particular risk of involvement as bully or bully victim. Parental education level was the only indicative of socioeconomic status associated with victimization. |

| Katsurada [63]. Japan. | 175 children, their parents, and teachers (175 mothers, 124 fathers, while teachers were not reported) Children’s sex: 45% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 62.24 months (SD = 5.05) Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the relationships between parents’ physical affection and children behavior in preschool settings. | Cross-sectional | Hostile, aggressive behavior (perpetration) | “Preschool Behavior Questionnaire”, Teacher report (PBQ; Behar and Stringfield, 1974). | Parental physical affection assessed by mothers’ and father’s reports in an ad hoc questionnaire. | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Children who received more physical affection from mothers or fathers were less likely to be aggressive at preschool. Only fathers’ physical affection was related with less aggressive behaviours when mothers’ physical affection was controlled. |

| Seçer, Gülay Ogerlman, Önder and Berengi [94]. Turkey. | 200 children, their mothers, and their teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 45% girls Age range = 5–6 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Investigate the relationship between mothers’ self-efficacy perception toward parenting and peer relations in school settings. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) Composite measure of peer victimization | Teachers’ reports through the aggressive behavior subscale of the “Child Behavior Scale” (CBS, Ladd and Profilet, 1996). Teachers’ reports through the “Peer Victimization Scale (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002). | Parenting self-efficacy perception assessed by mothers’ responses to the “Parenting Sense of Competence Scale” (Gibaud-Wallston and Wandersman, 1978). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Low parenting self-efficacy perception among mothers was associated with higher levels of peer aggression and peer victimization in schools’ settings. |

| Hammes, Crepaldi and Bigras [75]. Canada. | 278 children, their families, and teachers (79 teachers; the number of mothers and fathers not reported) Children’s sex: 50.7% girls Age range not reported. Mean age reported = 5.6 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Test the association between family functioning of preschoolers and their socioaffective competencies at the end of the first grade. | Short-term longitudinal | Anger/Aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports at two different points (at age 5 and 7 years), through the “Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation”, Teacher report (SCBE-30; LaFreniere and Dumas, 1996). | Family functioning reported by parents through the “Self-Report Family Inventory” (SFI; Beavers and Hampson, 1990). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Children with higher family harmony (less conflicting family relationships in the preschool period), display less aggressive behaviors in school settings during first grade. |

| Ziv [74]. United States. | 256 children, their families (242 mothers, and 14 grandmothers) and teachers number not reported) Children’s sex: 50.7% girls Age range = 48–63 months old Ethnicity: 43% black, 37% white, 11% Asian, 9% Latino | Examine the links between exposure to violence in the family/home and maladjusted behaviour in preschool. | Short-term longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports at two different points (three months apart), through the problem behavior scale used in the ACYF (2006) study. | Violence exposure in the family/home reported by mothers through the same measure used in the Family and Child Experiences Study (ACYF, 2006). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis Mediational path analysis Children’s’ social information process was tested as mediators | Children who reported witnessing and/or experiencing violence were more likely to behave aggressively with peers in the school setting. Children exposed to violence behave aggressively, at least in part, because they believe that aggression is appropriate in challenging peer situations. |

| Bigras and Crepaldi [96]. Canada. | 278 children, their families (217 mothers and 172 fathers), and teachers (n = 151) Children’s sex: not reported Age range not reported Mean age reported = 68.02 months old Ethnicity: not reported | Clarify the relationships between parental values and children’s social behaviours. | Cross-sectional | Anger/Aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports through the “Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation”- Teacher report (SCBE-30; LaFreniere and Dumas, 1996). | Parental values (individualism, collectivism and verticalism) reported by parents through an ad hoc questionnaire. | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Combinations of individualistic and collectivistic values (more observed in mothers that in parents), were associated with greater social competence in children and, therefore, less aggressive behaviours. |

| Jung, Raikes and Chazan-Cohen [83]. United States. | 914 children, their mothers and teachers (914 mother-teacher dyads) Children’s sex: 50.2% girls. Age range = 36–73 months old. Ethnicity: 38.1% European-American; 34% African American; 24.5 Hispanic American. | Compare behaviour problems of children of mothers with elevated depressive symptoms and non-elevated depressive symptoms. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Mothers’ and teachers reports through the “Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES) interview” (Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, 1998). | Maternal depression reported by mothers through the “Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scales” (CES-D-SF, Ross et al. 1983). | Bivariate and Multivariate analysis | Children of mothers with non-elevated depressive symptoms were reported to have more aggressive behaviors than children of mother with non-elevated depressive symptoms by their mothers’ rating of aggression. However, there were no differences in teachers’ rating of aggressive behaviors. |

| Meysamie et al. [65]. Iran. | 1403 children, their parents, and teachers (number mother, parents and teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 48% girls Age range = 3–6 years old Ethnicity: 38.1% Eurpean-American; 34% African American; 24.5 Hispanic-American | Estimate the prevalence and associated factors of childhood aggression. | Cross-sectional | Physical, verbal and relational aggression forms (perpetration) | Parents’ and teachers’ reports through the “Aggression Scale” developed by Shahim (2006). | Occupation and level of education of parents, history of smoking in mother during pregnancy, number of siblings, living with one or both parents, chronic disease in family and death of child relatives, reported by parents and teachers through an ad hoc questionnaire. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Results differ according to parents’ and teachers’ reports. Focusing on teachers’ reports of aggression in school settings, physical aggression was not associated with any family factor examined. Verbal aggression was associated with chronic disease in family members, and defeat of a family member. Relational aggression was associated with chronic disease in family members and maternal occupational status (employee). |

| Nelson et al. [61]. Russia. | 207 children, their parents, and teachers (204 mothers, 164 fathers, number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 52,1% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 5.1 years old (SD = 0.72) Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the relationship between parental psychological control and childhood physical and relational aggression. | Cross-sectional | Physical and relational aggression forms (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Psychological control dimensions (shaming/disappointment; constraining verbal expression; invalidating feelings, love withdrawal; guilt induction) reported by partners using items derived from the “Parental Psychological Control” scale (PPC, Hart and Robinson, 1995). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | All dimensions of psychological control, except for invalidating feelings, were associated with physical and relational aggression, although predominantly in same-sex parent–child dyads. |

| Seçer, Gülay Ogerlman and Önder [95]. Turkey. | 200 children, their fathers, and teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 48% girls Age range = 5–6 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Investigate the relationship between fathers’ self-efficacy perception toward parenting and peer relations in school settings. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) Composite measure of peer victimization | Teachers’ reports through the aggressive behavior subscale of the “Child Behavior Scale” (CBS, Ladd and Profilet, 1996). Teachers’ reports through the “Peer Victimization Scale (Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002). | Parenting self-efficacy perception assessed by fathers’ responses to the “Parenting Sense of Competence Scale” (Gibaud-Wallston and Wandersman, 1978). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Low parenting self-efficacy perception among fathers was associated with higher levels of peer aggression and peer victimization in schools settings. This relationship was stronger between fathers’ self-efficacy and peer victimization. |

| Jia, Wang and Shi [66]. China. | 1164 children, their parents, and teachers (53 teachers) Children’s sex: 45.1% girls Age range = 3–6 years old Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the relationship between parenting and proactive versus reactive aggression in preschool. | Cross-sectional | Proactive and reactive aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Aggressive Behavior-Teacher’s Checklist” (Dodge and Coie, 1987). | Parenting behavior covering two type of practices (supportive/engaged and hostile/coercive) assessed by parent’s responses to the “Parent Behavior Inventory” (PBI, Lovejoy et al., 1999). Family characteristics: family structure, household income, education and occupation (self-reported by parents). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Hostile/coercive parenting and less educated fathers were independent risk factors of both proactive and reactive aggression in the preschool setting. |

| Werner et al. [97]. United States. | 175 children, their mothers, and teachers (11 teachers) Children’s sex: 52% girls Age range not reported. Mean age reported = 4.30 years (SD = 0.62) Ethnicity: 85% white | Evaluate whether the quality of mothers’ conversation (coaching qualities) with preschoolers impacts the development of relational aggression in school. | Short-term longitudinal | Relational and physical aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports at two different points (twelve months apart), through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Social Coaching Qualities (elaboration, emotion references and rule violation) assessed through coding of mothers’ conversations with children during a coaching task in a laboratory session. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | After controlling for physical aggression, children whose mothers used average or high levels of elaborative, emotion-focuses social coaching abut relational conflicts were less relationally aggressive the following year. |

| Paschall et al. [85]. United States. | 1101 children, their mothers and teachers (number of teachers not reported Children’s sex: 50% girls Age range or Mean age not reported Ethnicity: 36% European American, 34.7% African American, 24.6% Hispanic American | Examine how maternal parenting behaviors at 3 years old were associated with children’s classroom aggression in pre-kindergarten. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of physical and verbal aggression (perpetration) | Teacher reports of aggressive behavior through the “Teacher Report Form of the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (TRF, Achenbach, 1991). | Maternal behaviors (supportiveness, negative regard, intrusiveness and detachment) were observationally assessed during a “Three-Bag” 10 min videotaped mother-child interaction task at 3-year-old child (Love et al., 2005). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Children exposed to detached parenting at 3 years old showed higher levels of classroom aggression in pre-kindergarten than children exposed to supportiveness parenting. |

| Jiménez et al. [103]. United States. | 1007 children, their mothers, and teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 51% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 61 months old Ethnicity: 46% African American, 36% White, 24% Latino | Examine relationships between adverse childhood experiences in early childhood and teacher reported behavioral problems in preschool. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Teacher reports of aggressive behavior through the “Teacher Report Form of the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (TRF, Achenbach, 1991). | Adverse childhood experiences (child maltreatment, parental substance use incarceration, caregiver treated violently) assessed through maternal reports at 5 years follow-up interview with ad hoc interview script, before conducting the teachers interviews about aggression. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Children who suffered three or more adverse childhood experiences were at higher risk of being involved in classroom aggression perpetration. |

| Narayana and Naerde [82]. Norway. | 1007 children, their mothers, and teachers (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 51% girls Age range not reported. Mean age reported = 61 months old Ethnicity: 46% African American, 36% White, 24% Latino | Analyze the associations between parental depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in preschool. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Mothers and Fathers reports of aggressive behavior on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and teachers’ reports of aggressive behavior through the “Teacher Report Form of the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist” (C_TRF, Achenbach and Rescolar, 2000), at 48 months after childbirth. | Parental depressive symptoms at 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 months after childbirth, assessed through the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-10). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Mothers’ depressive symptoms at 6 months after childbirth predicted aggressive behaviors at 48 months after childbirth, while fathers’ did not. Increase in paternal depression symptoms from 6 to 48 months were associated with more aggressive problems, while a corresponding maternal rise over the months did not predict aggressive behavior. |

| Baker, Jensen and Tisak [69]. United States. | 143 children, their parents, and teachers (number not reported) Children’s sex: 49.6% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 51.7 months (SD = 8.52) Ethnicity: 84.8% Caucasian | Test relations between proactive and reactive aggression, executive function and single-parent status. | Cross-sectional | Proactive physical/relational and reactive physical/relational aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Preschool Proactive and Reactive Aggression-Teacher Repot” (PPRA-TR, Ostrov and Crick, 2007). | Single-parent status self-reported by parents. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Children of single parents exhibit greater levels of both types of relational aggression (proactive and reactive), and reactive-physical aggression. |

| Matheson et al. [78]. Australia. | 69116 children, and teachers (number not reported) Children’s sex: 49.5% girls Age range not reported. Mean age reported = 5.6 years old (SD = 0.4) Ethnicity: not reported | Establish the independent and moderating effect of childhood maltreatment and parental schizophrenia disorders on early childhood social-emotional functioning. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression including physical aggression, bullying, among others (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Australian Early Development Census” (AEDC, Australian Government, 2009) at children’s aged 5 years old. | Child maltreatment and parental schizophrenia disorders assessed by government records. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Childhood maltreatment and parental schizophrenia disorders were related independently with higher aggressive behaviors in preschool. However, childhood maltreatment effect of aggressive behavior is greater in comparison to parental schizophrenia disorders. |

| Tzoumakis et al. [81]. Australia. | 69116 children, and teachers (number not reported) Children’s sex: 49.5% girls Age range not reported Mean age reported = 5.6 years old (SD = 0.4) Ethnicity: not reported | Analyze the impact of parental criminal offending on preschool aggression at age 5 years old. | Longitudinal | Composite measure of aggression including physical aggression, bullying, among others (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Australian Early Development Census” (AEDC, Australian Government, 2009) at children’s aged 5 years old. | Maternal and paternal criminal offending assessed by government records. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Maternal and paternal criminal offending was associated with high levels of aggression at 5 years old. Strength of the relationship was greater when parents were involved frequently in offences. |

| Baker et al. [70]. United States. | 89 children, their parents, and teachers (number not reported) Children’s sex: 48.5% girls Age range = 3–5 years old Mean age reported = 51.27 months (SD = 7.77) Ethnicity: not reported | Explore the associations between family socioeconomic level, theory of mind and aggressive behavior in preschool. | Cross-sectional | Relational and physical aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Socioeconomic status reported by parents. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Moderation analyses conducted: Theory of mind tested as moderator | Low socioeconomic status was related with higher scores on relational aggression. However, theory of mind moderated this relationships and children with high levels of theory of mind did not receive higher scores on relational aggression regardless the socioeconomic status of their families. |

| Kokanović and Opić [64]. Croatia | 669 children, their parents and teachers (numbers not reported) Children’s sex: 50.3% girls Age range = not reported Mean age = not reported Ethnicity: not reported | Study differences in aggressive and prosocial behaviours among preschool children in relation to family differences. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Teachers reports through the “Aggressive and Prosocial Behavior in Preschool Children” (PROS/AG, Žužul and Vlahović- Štetić, 1992) | Parents’ reports of sociodemographic data (family roles, number of siblings and single-parent status). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | There were no differences in aggressive behaviours among only children and children with siblings, and also between single-parent and two-parent families. |

| Navarro et al. [71]. Spain. | 577 children, their parents (mothers, 67.6%; fathers, 7.6%; both, 24.8%) and teachers (n = 577) Children’s sex: 49.9% girls Age = 5 years old, in the last assessment Ethnicity: not reported | Identify early individual and family risk factors (at age 3) of being peer victimised during preschool (ages of 4 and 5). | Longitudinal | Composite measure of peer victimization | Parents’ and teachers’ reports at age 4 and 5 through the “Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire” (SDQ, Goodman, 1997). | Parents’ reports at age 3 of problems during pregnancy (emotional problems, conflict, economic problems), history of abuse, parental practices (APQ-Pr, de la Osa et al., 2014), psychopathology (ASR, Achenbach and Rescorla, 2003). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Low socioeconomic status family, and parental practices characterised by lower norms at age 3 increased the risk of parents and teachers reporting persistent victimization at age 4 and 5. |

| Güngör et al. [99]. Turkey. | 90 children, their father (n = 90), and teachers (n = 35). Children’s sex: 46.7% girls Age range = 5–6 years old Mean age = not reported Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the relationships between peer aggression in preschool and fathers’ duration of work and time spent with children. | Cross-sectional | Composite measure of aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the aggressive behavior subscale of the “Child Behavior Scale” (CBS, Ladd and Profilet, 1996). | Fathers’ reports of educational background, occupation, working hour during weekdays and weekends, number of working days, duration of spending time with the child and activities do together assessed by an ad hoc form. | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Long working hours of fathers, decreased free days in a week, and not spending time with children increased the likelihood that children behave aggressively with their peers at school. |

| Yu et al., [91]. United States. | 133 children and their mothers (n = 133), and teachers (n = 35) Children’s sex: 47% girls Age range = not reported Mean age = 4.48 (SD = 0.91) Ethnicity: 100% Chinese American | Analyse the effects of two psychological control dimensions (love withdrawal and guilt induction) on children’s bullying behavior in preschool. | Short-term Longitudinal | Composite measure of bullying, including physical, verbal and relational bullying (perpetration) | Teachers reports at two different points (six months apart), through the “Teachers Rating Scale” (Hart and Robinson, 1996). | Mothers’ report of low withdrawal and guild induction assessed through the ”Psychological Control Measure” (Olsen et al., 2002). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses | Maternal love withdrawal predicted more bullying aggressive behavior, whereas guild induction predicted less preschool bullying 6 months later. |

| Mizokawa and Hamana [98]. Japan | 51 children and their mothers (n = 44), and teachers (n = 8) Children’s sex: 54.9% girls Age range = 58.71 months old Mean age = 65.14 months (SD = 3.73) Ethnicity: not reported | Examine the association between theory of mind, maternal emotional expressiveness and preschoolers’ aggressive behaviors. | Cross-sectional | Physical and relational aggression (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Mothers’ reports of positive and negative emotion towards their children assessed through a measure of self-expressiveness in mother-child relationship (Mizokawa, 2013). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Interact in analyses conducted with gender and theory mind | Boys with higher levels of theory of mind and mother showing high negative emotional expressiveness, shower higher relational aggression in the preschool setting. No effect was found for girls. |

| Ziv and Arbel [87]. Israel. | 115 children and their parents, and their teacher (number of teachers not reported) Children’s sex: 53.9% girls Age range = not reported Mean age = 68,5 months (SD = 6.04) Ethnicity: not reported | Study whether there are differences between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and their children’s social difficulties in preschool settings. | Cross-sectional | Author did not specifically analyse aggressive behaviors in school. Perpetration was included in a composite measure of socioemotional difficulties (including emotional difficulties, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention and peer relationship problems) | Teachers’ reports through the “Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire” (SDQ, Goodman, 1997). | Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian and permissive) assessed through the ”Parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (Robinson et al., 2001). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Mediational path analysis: Aggressive decision-making process was tested as mediator. | Both parents’ authoritative parenting style was associated with less social difficulties in preschool. Association between fathers authoritative parenting style and child social difficulties was not significant after aggressive decision-making process was entered into the equation. |

| Lau and Williams [88]. Hong Kong. | 168 children and their parents (158 mothers, 154 fathers), and their teacher (n = 167) Children’s sex: 52% girls Age range = 4–5 years old Mean age = 61 months (SD = 5.51) Ethnicity: 100% Hong Kong Chinese | Explore associations among emotional regulation in mothers and fathers and preschool children’s physical and relational aggression. | Short-term Longitudinal | Physical and relational aggression forms (perpetration) | Teachers’ reports at two different points (six months apart) through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Parents’ repots of emotional regulation (reappraisal, suppression) assessed through the “Emotional Regulation Questionnaire” (Gross and John, 2003). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Moderation analyses conducted: Child sex was tested as moderator | Higher levels of reappraisal and lower levels of suppression by mother were associated with higher child relational aggression. There were not significant association with fathers’ emotional regulation or moderation effect by child’s sex. |

| Lau, Chang and Casas [92]. Hong Kong. | 168 children and their parents (158 mothers, 154 fathers), and their teacher (n = 167) Children’s sex: 52% girls Age range = 4–5 years old Mean age = 61 months (SD = 5.51) Ethnicity: 100% Hong Kong Chinese | Analyse relationships between mothers’ and fathers’ physical coercion and psychological control and preschoolers’ use of physical and relational aggression in the school setting. | Short-term Longitudinal | Physical and relational aggression forms (perpetration) | Teachers’, mothers’ and fathers’ reports at two different points (six months apart) through the “Preschool Social Behavior Scale” (Crick et al., 1997). | Self-reports and partners’ reports of psychological control using items of the “Psychological Control Scale” adapted from previous measures (Nelson et al., 2013). Self-reports and partners’ reports of physical coercion using items derived from the “the “Parental Psychological Control” scale (PPC, Hart and Robinson, 1995). | Bivariate and Multivariate analyses Moderation analyses conducted: Children’s effortful control was tested as a moderator | Mothers’ and fathers’ physical coercion predicted children’s physical aggression and relational aggression, except fathers’ physical coercion which was unrelated to children’s relational aggression. Child effortful control moderated the effects of fathers’ (but not mothers’) physical coercion on child physical aggression and relational aggression. |

References

- Berkowitz, L. Aggression: Its Causes, Consequences, and Control; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ettekal, I.; Ladd, G.W. Developmental continuity and change in physical, verbal, and relational aggression and peer victimization from childhood to adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, L.C.; Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.; Côté, S.M. Development of aggression subtypes from childhood to adolescence: A group-based multi-trajectory modelling perspective. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, D.M.; Card, N.A. Overt and relational victimization: A meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social–psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrenkohl, T.I.; Catalano, R.F.; Hemphill, S.A.; Toumbourou, J.W. Longitudinal examination of physical and relational aggression as precursors to later problem behaviors in adolescents. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.C.; Frazer, A.L.; Blossom, J.B.; Fite, P.J. Forms and functions of aggression in early childhood. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.; Monks, C. Agresividad injustificada entre preescolares. Psicothema 2005, 17, 453–458. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8348 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Alink, L.R.A.; Mesman, J.; Van Zeijl, J.; Stolk, M.N.; Juffer, F.; Koot, H.M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van IJzendoorn, M.H. The early childhood aggression curve: Development of physical aggression in 10-to 50-month-old children. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E. Aggression. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Available online: http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/sites/default/files/dossiers-complets/en/aggression.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Campbell, S.B.; Shaw, D.S.; Gilliom, M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Crick, N.R.; Stauffacher, K. Relational aggression in sibling and peer relationships during early childhood. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 27, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N.R.; Ostrov, J.M.; Burr, J.E.; Cullerton-Sen, C.; Jansen-Yeh, E.; Ralston, P. A longitudinal study of relational and physical aggression in preschool. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 27, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Keating, C.F. Gender differences in preschool aggression during free play and structured interactions: An observational study. Soc. Dev. 2004, 13, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Taraschi, E. Like father, like son? The link between parents’ moral disengagement and children’s externalizing behaviors. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2015, 61, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersan, C. Physical aggression, relational aggression and anger in preschool children: The mediating role of emotion regulation. J. Gen. Psychol. 2020, 147, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Murray-Close, D.; Godleski, S.A.; Hart, E.J. Prospective associations between forms and functions of aggression and social and affective processes during early childhood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2013, 116, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseth, C.J.; Pellegrini, A.D. Methods for assessing bullying and victimization in schools and other settings: Some empirical comparisons and recommendations. In Preventing and Treating Bullying and Victimization; Vernberg, E.M., Biggs, B.K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou, M.; Andreou, E.; Botsoglou, K.; Didaskalou, E. Bully/victim problems among preschool children: A review of current research evidence. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, P.M.; Gutiérrez Rodríguez, H.; Checa Romero, M. Perception of bullying among prescholeers and primary school students. Rev. Educ. 2017, 377, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Adriany, V. ‘I don’t want to play with the Barbie boy’: Understanding Gender-Based Bullying in a Kindergarten in Indonesia. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.-j.; Lee, S.-h. Mothers’ Perceptions of the Phenomenon of Bullying among Young Children in South Korea. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Coppola, G. Bullying, empathic concern, and internalization of rules among preschool children: The role of emotion understanding. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 40, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, C.P.; Palermiti, A.; Ortega, R.; Costabile, A. A Cross-National Comparison of Aggressors, Victims and Defenders in Preschools in England, Spain and Italy. Span. J. Psychol. 2011, 14, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucaba, K.; Monks, C.P. Peer relations and friendships in early childhood: The association with peer victimization. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, C.; Smith, P. Peer, self and teacher nominations of participant roles taken in victimisation by five- and eight-year-olds. J. Aggress. Confl. Peac. Res. 2010, 2, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.D.; Boivin, M.; Brendgen, M.; Fontaine, N.; Arseneault, L.; Vitaro, F.; Bissonnette, C.; Tremblay, R.E. Predictive validity and early predictors of peer-victimization trajectories in preschool. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingault, J.B.; Côté, S.M.; Lacourse, E.; Galéra, C.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E. Childhood hyperactivity, physical aggression and criminality: A 19-year prospective population-based study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, R.E. Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: The “original sin” hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huitsing, G.; Monks, C.P. Who victimizes whom and who defends whom? A multivariate social network analysis of victimization, aggression, and defending in early childhood. Aggress. Behav. 2018, 44, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Smith, P.K.; Monks, C.P. Participant roles in peer-victimization among young children in South Korea: Peer-, Self-, and Teacher-nominations. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, S.; Monks, C.P.; Tsermentseli, S. Development of cool and hot executive function and theory of mind across early to middle childhood. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Kamper, K.E. Future directions for research on the development of relational and physical peer victimization. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, S.E.; Monks, C.P.; Tsermentseli, S. Cool and hot executive function as predictors of aggression in early childhood: Differentiating between the function and form of aggression. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 34, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Musitu, G. Family relationships and cyberbullying. In Cyberbullying Across the Globe; Navarro, R., Yubero, S., Larrañaga, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, M.-J.; Ayllón, E.; Tomás, I. Coping Strategies against Peer Victimization: Differences According to Gender, Grade, Victimization Status and Perceived Classroom Social Climate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godleski, S.A.; Kamper, K.E.; Ostrov, J.M.; Hart, E.J.; Blakely-McClure, S.J. Peer victimization and peer rejection during early childhood. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S.; Carrascosa, L. Cyber-control and cyber-aggression toward the partner in adolescent students: Prevalence and relationships with cyberbullying. Rev. Educ. 2022, 397, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, H.J.; Kendall, G.E.; Burns, S.K.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A. A scoping review of self-report measures of aggression and bullying for use with preadolescent children. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 33, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.K.; Koegler, E.; Johnson, S.D.; Murugan, V.; Wamser-Nanney, R. Guns and Intimate Partner Violence among Adolescents: A Scoping Review. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.P.; Arumugam, C.; Rangeela, E.; Raghavan, V.; Padmavati, R. Bullying among children and adolescents in the SAARC countries: A scoping review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Development. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/preschoolers.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Navarro, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S.; Víllora, B. Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.L. Are parents reliable in reporting child victimization? Comparison of parental and adolescent reports in a matched Chinese household sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 44, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrad, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy. The Matrix Method, 5th ed.; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, N.R.; Casas, J.F.; Mosher, M. Preschool Social Behavior Scale--Teacher Form. PsycTESTS Dataset 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFreniere, P.J.; Dumas, J.E. Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: The short form (SCBE-30). Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Profilet, S.M. The child behavior scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A.; Coie, J.D. Social-information-processing factors inreactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N.R.; Casas, J.F.; Ku, H.-C. Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, N.R. (University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, Minneapolis, USA). Children’s Social Behavior–Parent Report. Unpublished work.

- Administration on Children, Youth, and Families. Head Start Program Performance Measures: Second Progress Report; Department of Health and Human Servicies: Washington, DC, USA, 1998.

- Shahim, S. Overt and Relational Aggression among Elementary School Children. Psychol. Res. 2006, 9, 27–44. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=102134 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.C.; Mandleco, B.; Frost Olsen, S.; Hart, C.H. The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ). In Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques. Vol. 2: Instruments and Index; Perlmutter, B.F., Touliatos, J., Holden, G.W., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Gibaud-Wallston, J.; Wandersman, L.P. Parenting Sense of Competence Scale. PsycTESTS Dataset 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.A.; Yang, C.; Coyne, S.M.; Olsen, J.A.; Hart, C.H. Parental psychological control dimensions: Connections with Russian preschoolers’ physical and relational aggression. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.H. (Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA); Robinson, C.C. (Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA). Parental Psychological Control: An Instrument for Early Childhood. Unpublished work.

- Katsurada, E. The relationship between parental physical affection and child physical aggression among Japanese preschoolers. Child Stud. Asia-Pac. Contexts 2012, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokanović, T.; Opić, S.; Sisak Stari, K. Prevalence of Aggressive and Prosocial Behavior of Preschool Children in Relation to Family Structure. Croat. J. Educ. 2018, 20, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meysamie, A.; Ghalehtaki, R.; Ghazanfari, A.; Daneshvar-Fard, M.; Mohammadi, M.R. Prevalence and associated factors of physical, verbal and relational aggression among Iranian preschoolers. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2013, 8, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y. Relationship between parenting and proactive versus reactive aggression among Chinese preschool children. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 28, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, A.S.; Su, P.C. Mother vs. Father custody effects for Taiwanese preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 2000, 164, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.W.; Verlinden, M.; Berkel, A.D.V.; Mieloo, C.; van der Ende, J.; Veenstra, R.; Verhulst, F.C.; Jansen, W.; Tiemeier, H. Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: Do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter? BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.R.; Jensen, C.J.; Tisak, M.S. A closer examination of aggressive subtypes in early childhood: Contributions of executive function and single-parent status. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.R.; Jensen, C.J.; Moeyaert, M.; Bordoff, S. Socioeconomic status and early childhood aggression: Moderation by theory of mind for relational, but not physical, aggression. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 190, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.B.; Fernández, M.; De La Osa, N.; Penelo, E.; Ezpeleta, L. Warning signs of preschool victimization using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire: Prevalence and individual and family risk factors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.M.; Behalik, S.G.; El Soreety, W.H. Prevalence and factors associated with aggression among preschool age children at Baraem Bader Nursery School in Al-Asher 10th of Ramadan city, Egypt. Life Sci. J. 2011, 8, 929–938. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M.E.; Wade, R.; Lin, Y.; Morrow, L.M.; Reichman, N.E. Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20151839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziv, Y. Exposure to violence, social information processing, and problem behavior in preschool children. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes, P.S.; Crepaldi, M.A.; Bigras, M. Family functioning and socioaffective competencies of children in the beginning of schooling. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Bishop, C.M. Preschoolers’ aggression and parent–child conflict: A multiinformant and multimethod study. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2008, 99, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farver, J.A.M.; Xu, Y.; Eppe, S.; Fernandez, A.; Schwartz, D. Community violence, family conflict, and preschoolers’ socioemotional functioning. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, S.L.; Kariuki, M.; Green, M.J.; Dean, K.; Harris, F.; Tzoumakis, S.; Tarren-Sweeney, M.; Brinkman, S.; Chilvers, M.; Sprague, T.; et al. Effects of maltreatment and parental schizophrenia spectrum disorders on early childhood social-emotional functioning: A population record linkage study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L.; Lopez-Duran, N.; Lunkenheimer, E.S.; Chang, H.; Sameroff, A.J. Individual differences in the development of early peer aggression: Integrating contributions of self-regulation, theory of mind, and parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011, 23, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngee Sim, T.; Ping Ong, L. Parent physical punishment and child aggression in a Singapore Chinese preschool sample. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoumakis, S.; Dean, K.; Green, M.J.; Zheng, C.; Kariuki, M.; Harris, F.; Carr, V.J.; Laurens, K.R. The impact of parental offending on offspring aggression in early childhood: A population-based record linkage study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.K.; Nærde, A. Associations between maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and early child behavior problems: Testing a mutually adjusted prospective longitudinal model. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 196, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Raikes, H.H.; Chazan-Cohen, R. Maternal depressive symptoms and behavior problems in preschool children from low-income families: Comparison of reports from mothers and teachers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMulder, E.K.; Denham, S.; Schmidt, M.; Mitchell, J. Q-sort assessment of attachment security during the preschool years: Links from home to school. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschall, K.W.; Gonzalez, H.; Mortensen, J.A.; Barnett, M.A.; Mastergeorge, A.M. Children’s negative emotionality moderates influence of parenting styles on preschool classroom adjustment. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, J.F.; Weigel, S.M.; Crick, N.R.; Ostrov, J.M.; Woods, K.E.; Yeh, E.A.J.; Huddleston-Casas, C.A. Early parenting and children’s relational and physical aggression in the preschool and home contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 27, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, Y.; Arbel, R. Parenting practices, aggressive response evaluation and decision, and social difficulties in kindergarten children: The role of fathers. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Williams, K. Emotional regulation in mothers and fathers and relations to aggression in Hong Kong preschool children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.A.; Hart, C.H.; Yang, C.; Olsen, J.A.; Jin, S. Aversive parenting in China: Associations with child physical and relational aggression. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, H.Y. Peer victimization in Korean preschool children: The effects of child characteristics, parenting behaviours and teacher-child relationships. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2008, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Hart, C.H.; Yang, C.; Olsen, J.A. Longitudinal effects of maternal love withdrawal and guilt induction on Chinese American preschoolers’ bullying aggressive behavior. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Chang, L.; Casas, J.F. Examining effortful control as a moderator in the association of negative parenting and aggression among Hong Kong Chinese preschoolers. Early Educ. Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyse, E.; Verschueren, K.; Doumen, S. Preschoolers’ attachment to mother and risk for adjustment problems in kindergarten: Can teachers make a difference? Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secer, Z.; Gulay Ogelman, H.; Onder, A.; Berengi, S. Analysing Mothers’ Self-Efficacy Perception towards Parenting in Relation to Peer Relationships of 5–6-year-old Preschool Children. Educ. Sci.-Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 2001–2008. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1000906 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Seçer, Z.; Gülay Ogelman, H.; Önder, A. The analysis of the relationship between fathers’ parenting self-efficacy and the peer relations of preschool children. Early Child Dev. Care 2013, 183, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigras, M.; Crepaldi, M.A. The differential contribution of maternal and paternal values to social competence of preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 2013, 183, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, N.E.; Eaton, A.D.; Lyle, K.; Tseng, H.; Holst, B. Maternal social coaching quality interrupts the development of relational aggression during early childhood. Soc. Dev. 2014, 23, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizokawa, A.; Hamana, M. The relationship of theory of mind and maternal emotional expressiveness with aggressive behaviours in young Japanese children: A gender-differentiated effect. Infant Child Dev. 2020, 29, e2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, H.; Gülay Ogelman, H.; Körükçü, Ö.; Erten Sarikaya, H. The predictive effect of fathers’ durations of working and spending time with their children on the aggression level of five–six year-old children. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol 1. Attachment; Basic: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, D.G.; Hodges, E.V.; Egan, S.K. Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and a new model of family influence. In Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized; Juvonen, J., Graham, S., Eds.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Estévez, E.; Murgui, S. Ambiente comunitario y actitud hacia la autoridad: Relaciones con la calidad de las relaciones familiares y con la agresión hacia los iguales en adolescentes. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.; Alsaker, F.D. Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, C.P.; Smith, P.K.; Kucaba, K. Peer Victimisation in Early Childhood; Observations of Participant Roles and Sex Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno, P.M.; del Castillo, H.; Abril-López, D. Perceptions of Bullying amongst Spanish Preschool and Primary Schoolchildren with the Use of Comic Strips: Practical and Theoretical Implications. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Espelage, D.L.; Polanin, J.R.; Hong, J.S. A meta-analytic review of school-based anti-bullying programs with a parent component. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machimbarrena, J.M.; González-Cabrera, J.; Garaigordobil, M. Variables familiares relacionadas con el bullying y el cyberbullying: Una revisión sistemática. Pensam. Psicol. 2019, 17, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, J.D.; Thompson, M.D. Adaptive and maladaptive parenting: Perspectives on risk and protective factors. In Handbook of Early Childhood Intervention, 2nd ed.; Shonkoff, J.P., Meisels, S.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Buelga, S.; Cava, M.J.; Iranzo, B. Efficacy of the Prev@cib 2.0 program in cyberbullying, helping behaviors and perception of help from the teacher. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 20, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Terms |

|---|

| 1. (“preschool *” OR “preschool children” OR “preschool-aged children” OR “early child*” OR “2–6 yrs”).ti |

| 2. (“victim *” OR “perpetrat *” OR “aggress *” OR “bullying” OR “bully” OR “bully/victim” OR “peer aggress *” OR “peer violen *” OR “peer victim *” OR “peer abus *”).ti |

| 3. (“family” OR “families” OR “family context” OR “parent *” OR “mother” OR “father”).ti |

| 4. Searches 1, 2 and 3 were performed in each database. |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Qualitative and quantitative research published in peer-reviewed journals. | Articles describing interventions or prevention programmes, literature reviews, systematic reviews, conference papers, doctoral theses and newspaper articles. |

| Participants aged two to six years old. | Participants who were less than two or more than six years old. |

| Participants in the study had to belong to general populations. | Clinical samples or subgroups. |

| Research analysing aggressive peer interactions in school environments. | Research analysing aggressive interactions beyond peer relationships in school settings. |

| Research examining the relationship of preschool aggression using family or parental variables as predictor variables. | Research examining the relationship of preschool aggression not using family or parental variables as predictor variables. |

| Published in English and Spanish. | Published in languages other than English and Spanish. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Navarro, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S.; Víllora, B. Families, Parenting and Aggressive Preschoolers: A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Family Variables Related to Preschool Aggression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315556

Navarro R, Larrañaga E, Yubero S, Víllora B. Families, Parenting and Aggressive Preschoolers: A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Family Variables Related to Preschool Aggression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315556

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavarro, Raúl, Elisa Larrañaga, Santiago Yubero, and Beatriz Víllora. 2022. "Families, Parenting and Aggressive Preschoolers: A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Family Variables Related to Preschool Aggression" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315556

APA StyleNavarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2022). Families, Parenting and Aggressive Preschoolers: A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Family Variables Related to Preschool Aggression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315556