Strengthening Equity and Inclusion in Urban Greenspace: Interrogating the Moral Management & Policing of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Toronto Parks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Greenspace Access as an Environmental Determinant of Health

2.2. Greenspace Access & Socio-Environmental Justice

2.3. Urban Parks and Greenspace as Political & Moral Landscapes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Key Informant Interviews

3.3. Key Document Content Analysis

3.4. Ground-Truthing

4. Results

4.1. Morality in Greenspace Management

I think one of the things in the municipal code is ‘any use of a park or public space that infringes on the enjoyment of another person’ [is an infraction]. Which is so problematic to me because, then you know you’re again deciding who’s enjoyment and use is correct and takes precedence over someone else’s enjoyment and use of a public space. And we see how that very kind of innocuous seeming language is kind of weaponized in these situations.(Environmental Planner)

I mean you know, for as long as humanity has existed parks and public spaces have been places for heterosexuals to meet, right? And you know, we can all think of pictures, you know in Paris of heterosexual couples kissing on the you know banks. Well you know why is it only okay for heterosexual couples to do that to have obvious you know sexual desire for each other in a public space?(Politician)

4.2. Policing & Exclusion of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Greenspace

I mean it was always policed, there were always police and there were always arrests. So that was the shadow hanging over the use of parks.(Politician)

I think about what happened in Marie Curtis park a couple of years ago. That wildly disproportionate sting operation that I don’t think resulted in any criminal charges. It was just a horrible display of homophobia by the Toronto police […] it brought up again, the sort of really bad history between the police and the queer community.(Queer Activist)

- Any officer is authorized to inform a person of the provisions of this chapter and request compliance with it.

- Any officer is authorized to order a person believed by the officer to be contravening or who has contravened any provision of this chapter to:

- (1)

- Stop the activity constituting or contributing to the contravention;

- (2)

- Remove from the park to a pound or storage facility any animal or thing owned by or in control of the person who the officer believes is or was involved in the contravention; or

- (3)

- Leave the park.

I’m scared of the police for sure, because I don’t trust them. And I never will, never have. Police are so out of place in a park.(Queer Activist)

Policing… doesn’t have a place in public park space, it seems to me.(Politician)

You know it’s sort of borderline okay if it’s heterosexual. But it’s absolutely not okay if it’s homosexual. So I mean I think there’s the fact that when we’ve used it the same way that straight people have used public spaces, it’s been criminalized in a way that heterosexuals using that space is not—I mean what is a cop’s reaction to kids making out, you know, in a public space on a beach let’s say? […] The difference between them and two men making out would be an arrest and still is apparently, right?(Politician)

4.3. 2SLGBTQ+ Inclusion in Greenspace Accessibility Policy & Practice

I think Toronto definitely is lacking in sort of the quality of accessibility that we have within the city. And that is to greenspace and transportation networks. I know there’s definitely things in the works to improve that for sure, but I think we should take it even further.(Urban Planner)

[We must consider]… whether the design and the amenities, and the programming in that space are ones that meet your needs. So that could be a physical accessibility limitation, there’s lots of those in parks. But it could also be, you know, like a cultural limitation as well…And, so when I think about accessibility, I think of those different levels.(Environmental Planner)

They don’t often think about accessibility in terms of sort of cultural or even social elements around who feels you know… welcome in a space or feeling like you know there’s something there that reflects the person, who you are and how you want to use the space.(Queer Activist)

What can happen in that space and who is meant to use it and what is the correct way of using a park or a public space and what is an incorrect way? I think, you know, people always talk about parks as these democratic spaces that are open for everyone, and you know, sometimes they’re talked about as neutral spaces in our cities and I think the more I’ve learned about parks and the more I’ve worked in this area, I realized that that’s that’s not true at all. They’re definitely not neutral spaces, they’re highly governed and they’re not open to everyone and that’s by design.(Environmental Planner)

I think there are lots of really great people who are thinking this way already. I don’t think it’s institutionalized in a city setting in terms of how we plan and operate parks, but you know there’s a lot of really amazing advocates and urban thinkers I think that are already kind of raising this. We need to think about the social as much as we need to think about or even more than we need to think about the physical because that’s such an important element of inclusion, equity and access.(Urban Planner)

I think one of the aspects of public parks generally that could be changed is just to mark them as queer positive spaces, to have a pride symbol there and say this is a queer positive space and that signals to people who are going there looking to you know, like beat up queers or, like target queers, it signals to them that they’re not welcome doing that there, it makes it safer and welcoming to queers.(Urban Planner)

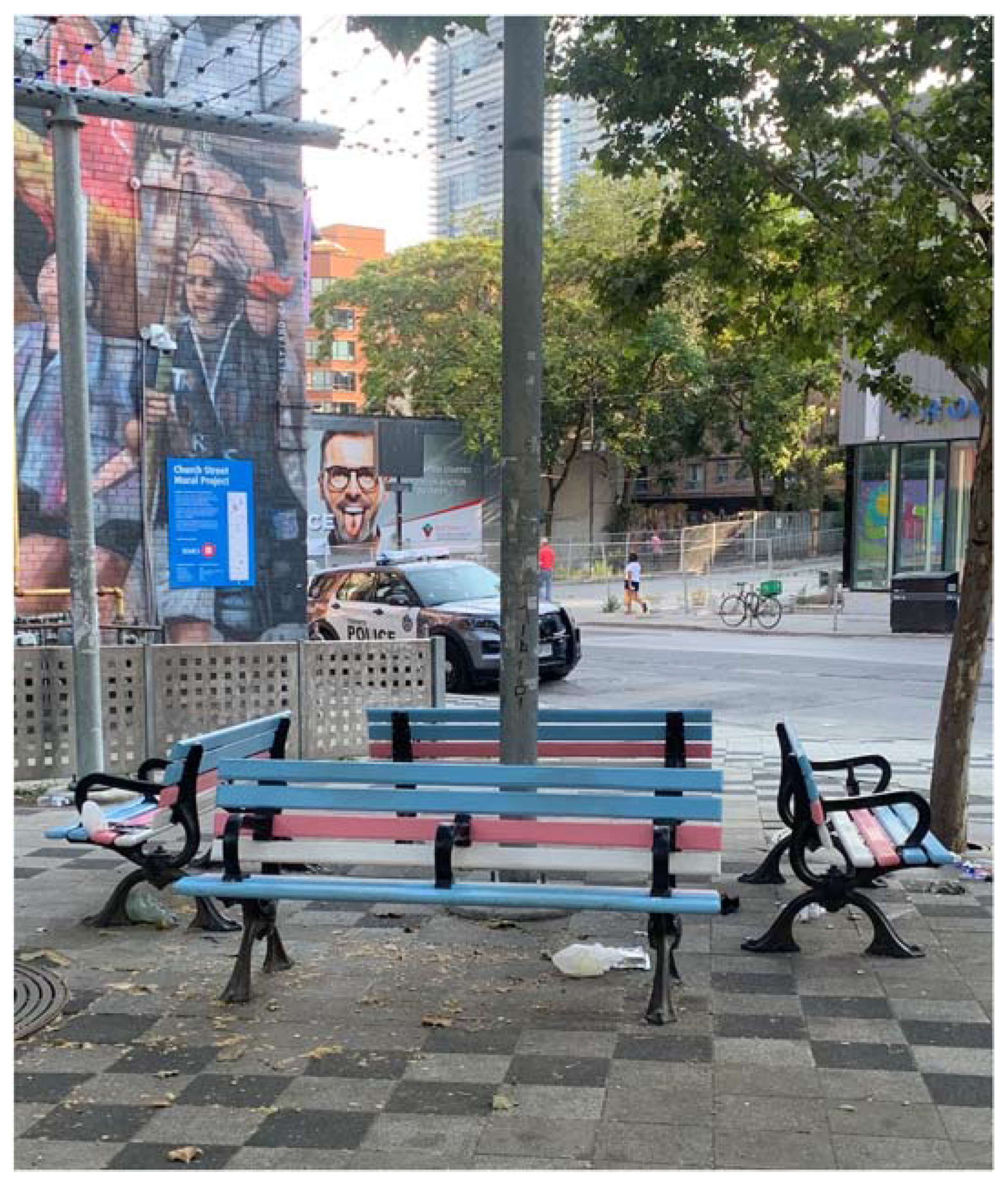

So we put some trans and rainbow benches in that park. You know the rainbow crosswalks, trans crosswalks, I was kind of part of the group that did some of that. So these are the symbols, right? So it’s a good way to say you are welcome, it’s clear, it’s coded, it’s feasible. But it’s kinda like pride [parades/celebrations], when people are still hungry and homeless the day after. So what about the day after, when people are still sleeping in parks? I find myself making contradictions in my life, trying to make a difference. But the benches do seem like a good symbolic thing.(Queer Activist)

4.4. Perspectives on Strengthening Equity in Sustainable Greenspace Management

It would be really great if there’s no police in parks, but then you need some kind of emergency, you know, people with healthcare training, for example, who were there on call or wandering around so there’s some way of accessing some help.(Greenspace Activism Organization Employee)

There are other ways of making that safe. When we look at defunding police maybe some of the money could go to much more sensitive managers of public spaces that could be kind of there to help people if something goes awry. They would be first aid trained, you know, have naloxone training or whatever like someone who is looking out for the health of the people using the space, rather than someone that’s looking at policing the space, I mean that would be a huge step forward. It seems to me in public spaces a way better use of the public purse than to have police ride through on their horses or just walk through. Those are scary. And with good reason, because you know they kill people, they hurt people and they imprison people.(Politician)

[Removal of police presence] signals to queers that it’s okay to be here and then back it up by keeping the police away from there, and having someone that can, you know, somebody who is looking after the safety of everybody involved, but that’s not the police. And that’s traditionally not the police, it won’t be the police, …this is about safety of the people using the park, it’s not about policing the people in the park.(Queer Activist)

I think it involves many different partners, it has to involve the community. Otherwise, you’re not going to really be creating truly accessible inclusive places for people. But a lot of it has to come from the city. They hold a lot of the power in public spaces, they write the rules. They divvy up the funding. And so there’s a lot of responsibility on the city to, I think, initiate some of these conversations. It’s important for community members and advocates to push on things, but ultimately, the city has to be the one to be flexible and courageous enough to try something new.(Environmental Planner)

Ultimately it belongs to us… It’s our space… so let us use it… And that’s a community decision, and I think the more local, in a sense, the better, because we know our own communities, and we know what we need. Let’s have more greenspace, let’s make space safe by keeping police out of it, and let’s sign it and make it safe, by the way it’s managed for everyone, including people that have nothing.(Queer Activist)

Systems that are in place that are often harmful and often possess several gaps which lead to the exclusion and often discriminatory development practices that we see today within the City of Toronto… For example, when talking about acknowledging that there are different genders that exist, and not just leaving it to woman or man or mom or father and stuff like that within policies. That needs to be more diverse and not just talking about the nuclear family because that’s a very outdated concept and the nuclear family is also something that is not really prominent in today’s times right? Families look different. Policy is just so behind… not only the language needs to be updated, but the concepts and ideas surrounding it as well.(Urban Planner)

When you read the Provincial Policy Statement, for instance it’s a very interesting document in a way that it’s quite idealistic. First time I read it, it was just like oh my God, this is amazing, let’s implement it as written. And then you realize how this is translated into municipal policies in a way that is like whatever we’re not going to really pay attention, or we’re just going to pretend that we’re listening to it and not going to do anything about it… to have any effective change in any way. I know there’s a lot of people that are very critical to planning as a science as a whole, because at the end of the day, we’re just upholding status quo.(Environmental Planner)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jennings, V.; Gaither, C.J.; Gragg, R.S. Promoting Environmental Justice Through Urban Green Space Access: A Synopsis. Environ. Justice 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Larson, L.; Yun, J. Advancing Sustainability through Urban Green Space: Cultural Ecosystem Services, Equity, and Social Determinants of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mears, M.; Brindley, P. Measuring Urban Greenspace Distribution Equity: The Importance of Appropriate Methodological Approaches. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2019, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijl, R. Never waste a good crisis: Towards social sustainable development. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 102, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, J.M.; Cook, S. Seizing the opportunity to do things differently: Feminist ideas, policies and actors in UN Women’s ‘Feminist plan for sustainability and social justice. Glob. Soc. Policy 2022, 22, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, C.S. Just sustainability? sustainability and social justice in professional codes of ethics for engineers. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2013, 19, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.W.; Grineski, S.E.; Morales, D.X. Environmental injustice and sexual minority health disparities: A national study of inequitable health risks from air pollution among same-sex partners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga-Teran, A.; Gerlak, A. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Analyzing Questions of Justice Issues in Urban Greenspace. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, S.; Davis, C.; Dean, J.; Onilude, Y.; Rishworth, A.; Wilson, K. Exploring immigrant wellbeing and settlement in urban and rural greenspaces of encounter. Wellbeing Sp. Soc. 2022; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, M. Anti-gay attack near Hanlan’s Point leaves victim unconscious. DH News. 2021. Available online: https://dailyhive.com/toronto/anti-gay-attack-hanlans-point (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Grozelle, R. The Rise of Gay Liberation in Toronto: From Vilification to Validation. Inq. J. 2017, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Janus, A. Some Charges Dropped in ‘Project Marie’ Etobicoke Park Sex Sting. CBC. 2017. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-marie-charges-dropped-1.4379087 (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Byrne, J.; Wolch, J. Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future directions for geographic research. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 743–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Towards a better understanding of the relationship between greenspace and health: Development of a theoretical framework. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 118, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.S.; Robinson, P.J.; Millward, A.A. Canopy of advantage: Who benefits most from city trees? J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 208, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, R.; Zhou, S. The spatial heterogeneity of urban green space inequity from a perspective of the vulnerable: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Cities 2022, 130, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, F.; Nygaard, A.; Stone, W.M.; Levin, I. Accessing green space in Melbourne: Measuring inequity and household mobility. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 207, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffimann, E.; Barros, H.; Ribeiro, A. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Green Space Quality and Accessibility-Evidence from a Southern European City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 15, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heynen, N. Urban political ecology III: The feminist and queer century. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2017, 41, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.M.; Chakraborty, J. Street trees and equity: Evaluating the spatial distribution of an urban amenity. Environ. Plan. 2009, 41, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, A. An archaeology of fear and environmental change in Philadelphia. Geoforum 2006, 37, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, S.; Ryan, B.; Jalbert, Y.; Rowe, B. Reclaiming Space-Regaining Health. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2002, 14, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritaworn, J. Queering Urban Justice: Queer of Colour Formations in Toronto; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hern, M.; Couture, S.; Couture, D.; Couture, S. On This Patch of Grass: City Parks on Occupied Land; Fernwood Publishing: Black Point, NS, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Catungal, J.P.; McCann, E.J. Governing sexuality and park space: Acts of regulation in Vancouver, BC. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2010, 11, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, K. Rethinking the nature of urban environmental politics: Security, subjectivity, and the non-human. Geoforum 2009, 40, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.L.; Avlonitis, G.; Ernstson, H. Ecological outcomes of civic and expert-led urban greening projects using indigenous plant species in Cape Town, South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 127, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Lessard, D.; Heston, L.; Nordmaken, S. Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies; University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, N.J.; Cope, M.; Gillespie, T.W.; French, S. Key Methods in Geography; SAGE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Review. Most Diverse City in the World. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-city-rankings/most-diverse-city-in-the-world (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- City of Toronto. Population Demographics. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/99b4-TOHealthCheck_2019Chapter1.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. Pride in Canada. Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/world-pride-2014-toronto (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Archer, B. The evolution of Toronto’s Church Street Gaybourhood. 2010. Available online: http://www.yongestreetmedia.ca/features/churchstreet0623.aspx (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Xtra Spark. Project Marie is the Latest Chapter in Toronto Police’s Long History of Targeting Queer Sex. 2016. Available online: https://xtramagazine.com/sponsored-post/project-marie-is-the-latest-chapter-in-toronto-polices-long-history-of-targeting-queer-sex-72525 (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Wong-Tam, K. Statement on Project Marie. 2016. Available online: https://www.kristynwongtam.ca/statement_on_project_marie (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Rieti, J.; Toronto Police Should Drop Project Marie Charges, City and Provincial Politicians Say. CBC. 2016. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-marie-reaction-1.3858328 (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Burla, L.; Knierim, B.; Barth, J.; Liewald, K.; Duetz, M.; Abel, T. From Text to Codings. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labuschagne, A. Qualitative Research-Airy Fairy or Fundamental? Qual. Rep. 2015, 8, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaton, F. Assessing biases, relaxing moralism: On ground-truthing practices in machine learning design and application. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 20539517211013569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, E.; Meier, P. Good Symbolic Representation: The Relevance of Inclusion. PS Politi. Sci. Politi. 2018, 51, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. Municipal Code Chapter 608: Parks. 2018. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/municode/1184_608.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- City of Toronto. Parkland Strategy (Final Report). 2019. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/97fb-parkland-strategy-full-report-final.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- City of Toronto. Parks Plan. 2013–2017. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/98f1-parksplan.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- City of Toronto. Toronto Parks and Recreation Facilities Master Plan, 2019–2038. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2017/ex/bgrd/backgroundfile-107775.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Agyeman, J. Toward a ‘just’ sustainability? Contin. J. Media Cult. Stud. 2008, 22, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M. Just sustainability in urban parks. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Arons, W. Queer Ecology/Contemporary Plays. Theatre J. 2012, 64, 565–582. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41819890 (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Foster, J.; Sandberg, L.A. Post-industrial urban greenspace: Justice, quality of life and environmental aesthetics in rapidly changing urban environments. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, M.; Rice, C. Gender and Women’s Studies: Critical Terrain, 2nd ed.; Women’s Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, P.; Collins, A.; Gorman-Murray, A. Introduction: Sex, consumption and commerce in the contemporary city. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, O.H. Má-ka Juk Yuh: A Genealogy of Black Queer Liveability in Toronto. In Queering Urban Justice; Haritwaron, J., Moussa, G., Ware, S., Rodríguez, R., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M. Publics and Counterpublics; Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M. Citizen participation in urban governance in the context of democratization: Evidence from low-income neighbourhoods in Mexico. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G. ‘Why can’t they meet in bars and clubs like normal people?’: The protective state and bioregulating gay public sex spaces. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018, 19, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C.G.; Buckley, G.L.; Grove, J.M.; Sister, C. Parks and People: An Environmental Justice Inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Public Sp. Read. 2021, 99, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J. Vauxhall’s post-industrial pleasure gardens: ‘death wish’ and hedonism in 21st-century London. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; McLeod, M. Is Public Sex in Parks a Public Safety Concern? Spacing Magazine. 2016. Available online: http://spacing.ca/national/2016/11/28/public-sex-parks-public-safety-concern/ (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Plaster, J. Imagined Conversations and Activist Lineages: Public Histories of Queer Homeless Youth Organizing and the Policing of Public Space in San Franciscos Tenderloin, 1960s and Present. Radic. Hist. Rev. 2012, 113, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, J. “Ground-truthing” representations of social space: Using lefebvre’s conceptual triad. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2008, 28, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, H.V.S.; Lamarca, M.G.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Anguelovski, I. Are green cities healthy and equitable? unpacking the relationship between health, green space and gentrification. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2017, 71, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A. Inclusive planning of urban nature. Ecol. Restor. 2008, 26, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnik, P. Urban Green: Innovative Parks for Resurgent Cities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Key Documents Analyzed |

|---|

| Toronto Parks Plan (2013) |

| Planning Act (2018) |

| Toronto Parks and Recreation Facilities Master Plan (2017) |

| City of Toronto Parkland Strategy (Final Report) (2019) |

| City of Toronto Municipal Code Chapter 608: Parks (2018) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, C.; Edge, S. Strengthening Equity and Inclusion in Urban Greenspace: Interrogating the Moral Management & Policing of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Toronto Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315505

Davis C, Edge S. Strengthening Equity and Inclusion in Urban Greenspace: Interrogating the Moral Management & Policing of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Toronto Parks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):15505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315505

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Claire, and Sara Edge. 2022. "Strengthening Equity and Inclusion in Urban Greenspace: Interrogating the Moral Management & Policing of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Toronto Parks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 15505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315505

APA StyleDavis, C., & Edge, S. (2022). Strengthening Equity and Inclusion in Urban Greenspace: Interrogating the Moral Management & Policing of 2SLGBTQ+ Communities in Toronto Parks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315505