A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. A Job Demands–Resources Model for Principals’ Well-Being

2.2. Emotional Labor and Emotion Regulation

2.3. Emotion Regulation as Personal Resource in the JD-R Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Emotional Job Demands and Trust in Colleagues

3.2.2. Emotion Regulation Strategies

3.2.3. Kindergarten Principals’ Well-Being

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Construct Validity of the Scales

4.2. Descriptive Results

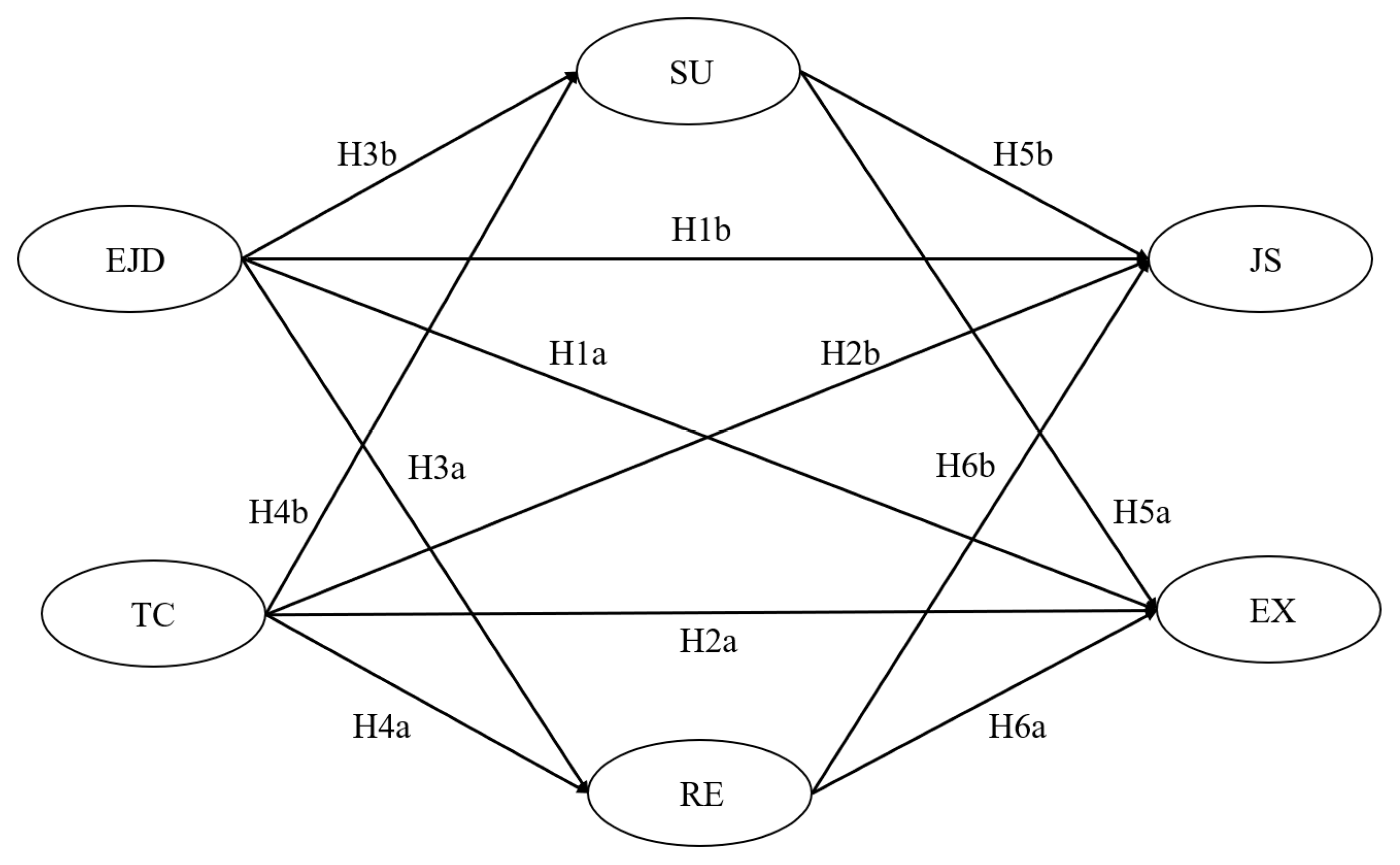

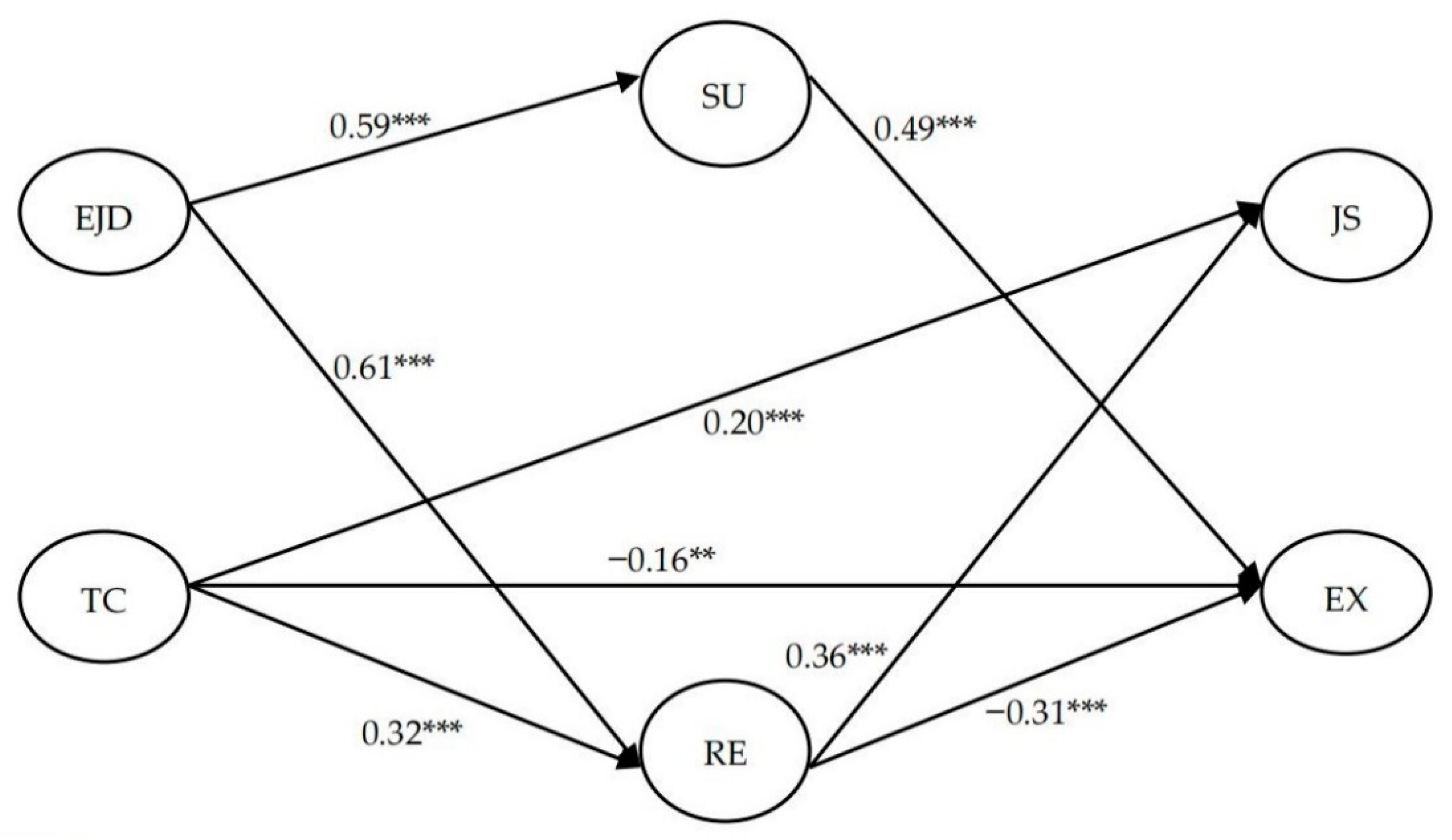

4.3. SEM Results

4.4. Mediation Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Influences of Job Resources and Job Demands on Principal Emotion Regulation and OWB

5.2. Mediation of Principals’ Emotion Regulation

6. Implications for Practice

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results: Students’ Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley, D.; Hargreaves, A.; Washington-Wangia, S. The sustainability and unsustainability of teachers’ and leaders’ well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 92, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.; Riley, P. Emotional demands, emotional labour and occupational outcomes in school principals: Modelling the relationships. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Development and validation of the Principal Emotion Inventory: A mixed-methods approach. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, J.E.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P.J. The structure of occupational well-being: A study among Dutch teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, T. Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Child. Educ. J. 2017, 45, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.; Crawford, M.; Oplatka, I. An affective paradigm for educational leadership theory and practice: Connecting affect, actions, power and influence. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 22, 617–628. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Beatty, B. Leading with Teacher Emotions in Mind; Crowin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- To, K.; Yin, H. Being the weather gauge of mood: Demystifying the emotion regulation of kindergarten principals. Asia-Pac. Edu. Res. 2021, 30, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, W. Work environment characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of emotion regulation strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Stebner, F.; Linninger, C.; Kunter, M.; Leutner, D. A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: Applying the job demands-resources model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovich, I.; Eyal, O. Educational leaders and emotions: An international review of empirical evidence 1992–2012. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 129–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M. Emotional coherence in primary school headship. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oplatka, I. Empathy regulation among Israeli school principals: Expression and suppression of major emotions in educational leadership. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2017, 27, 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I.; Eyal, O. Good cop, bad cop: Exploring school principals’ emotionally manipulative behaviours. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Professional standards for teachers and school leaders: Interrogating the entanglement of affect and biopower in standardizing processes. J. Prof. Cap. Commu. 2018, 3, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U.; Kunter, M.; Trautwein, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Baumert, J. Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach burnout inventory. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources, 3rd ed.; Zalaquett, C.P., Wood, R.J., Eds.; The Scarecrow Press: London, UK, 1997; pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labour. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.J.; Dore, T.P.; O’Donovan, K.M. Associations of personality and emotional intelligence with display rule perceptions and emotional labour. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2008, 44, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, J.; Weisz, R. Emotional Intelligence as a Moderator of Affectivity/Emotional Labor and Emotional Labor/Psychological Distress Relationships. Psychol. Stud. 2011, 56, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Melloy, R.C. The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A.; Schneider, B. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Schewe, A.F. On the costs and benefits of emotional labour: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Tran, V.; Brotheridge, C.M.; Gross, J.J. Using an emotion regulation framework to predict the outcomes of emotional labor. In Emotions in Groups, Organizations and Cultures; Härtel, C.J., Ashkanasy, N.M., Zerbe, W.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 5, pp. 245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A. Smiling for a wage: What emotional labor teaches us about emotion regulation. Psycho. Inq. 2015, 26, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J.; Mac Ruairc, G. Different worlds: The cadences of context, exploring the emotional terrain of school principals’ practice in schools in challenging circumstances. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K. Emotional expression at different managerial career stages: Female principals in Arab schools in Israel. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Yin, H.; Ke, Z. Employees’ emotional labor and emotional exhaustion: Trust and gender as moderators. Soc. Beh. Pers. 2018, 46, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; DeChurch, L.A.; Wax, A. Moving emotional labour beyond surface and deep acting: A discordance-congruence perspective. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 6–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.M.; Wang, X.Q. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, F.; Lun, V.M.-C. Emotional labor and occupational well-being: A latent profile analytic approach. J. Individ. Dif. 2015, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Wray, S.; Strange, C. Emotional labour, burnout and job satisfaction in UK teachers: The role of workplace social support. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarotti, S.; Biassoni, F.; Villani, D.; Prunas, A.; Velotti, P. Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: Implications for subjective and psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Louis, A.C.; Rapaport, M.; Poirier, L.C.; Vallerand, R.J.; Dandeneau, S. On emotion regulation strategies and well-being: The role of passion. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 1791–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. The effect of teachers’ emotional labour on teaching satisfaction: Moderation of emotional intelligence. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Trust matters: Leadership for Successful Schools, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.L.; Au, W.T. Teaching satisfaction scale: Measuring job satisfaction of teachers. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling andconfirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Walker, A. Building emotional principal-teacher relationships in Chinese schools reflflecting on paternalistic leadership. Asia-Pac. Edu. Res. 2021, 30, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y. Leading teachers’ emotions like parents: Relationships between paternalistic leadership, emotional labor and teacher commitment in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Yoo, S.H.; Nakagawa, S. Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Miles, E.; Sheeran, P. Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 775–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, B.R. The emotions of educational leadership: Breaking the silence. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2000, 3, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, H.; Wang, M. Leading with teachers’ emotional labour: Relationships between leadership practices, emotional labour strategies and efficacy in China. Teach. Teach. 2018, 24, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leader. Manag. 2020, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ye, J. Teacher leadership for professional development in a networked learning community: A Chinese case study. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the relationships among instructional leadership, professional learning communities and teacher self-efficacy in China. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional job demands | 4.32 | 0.64 | (0.82) | |||||

| 2. Trust in colleagues | 5.62 | 0.52 | 0.39 ** | (0.95) | ||||

| 3. Reappraisal | 4.44 | 0.51 | 0.60 ** | 0.55 ** | (0.86) | |||

| 4. Suppression | 3.91 | 0.80 | 0.42 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.49 ** | (0.70) | ||

| 5. Emotional exhaustion | 2.41 | 1.23 | 0.02 | −0.21 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.21 ** | (0.91) | |

| 6. Job satisfaction | 4.29 | 0.70 | 0.36 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.07 | (0.94) |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Mediation Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation Variable | Estimates (SE) | p | 95% CI | ||

| EJD | EX | SU | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.000 | [0.34, 0.88] |

| RE | −0.19 (0.06) | 0.003 | [−0.73, −0.18] | ||

| JS | RE | 0.22 (0.04) | 0.000 | [0.13, 0.31] | |

| TC | JS | RE | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.000 | [0.09, 0.27] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, X.; Dan, Q.; Wu, Z.; Luo, S.; Peng, X. A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215030

Zheng X, Dan Q, Wu Z, Luo S, Peng X. A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215030

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Xin, Qinyuan Dan, Zhimin Wu, Shengquan Luo, and Xinying Peng. 2022. "A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 15030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215030

APA StyleZheng, X., Dan, Q., Wu, Z., Luo, S., & Peng, X. (2022). A Job Demands–Resources Perspective on Kindergarten Principals’ Occupational Well-Being: The Role of Emotion Regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215030