The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Serial Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Intolerance of Uncertainty

2.2.2. Maladaptive Coping Strategies

2.2.3. Fear of Missing Out

2.2.4. Problematic Social Media Use

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

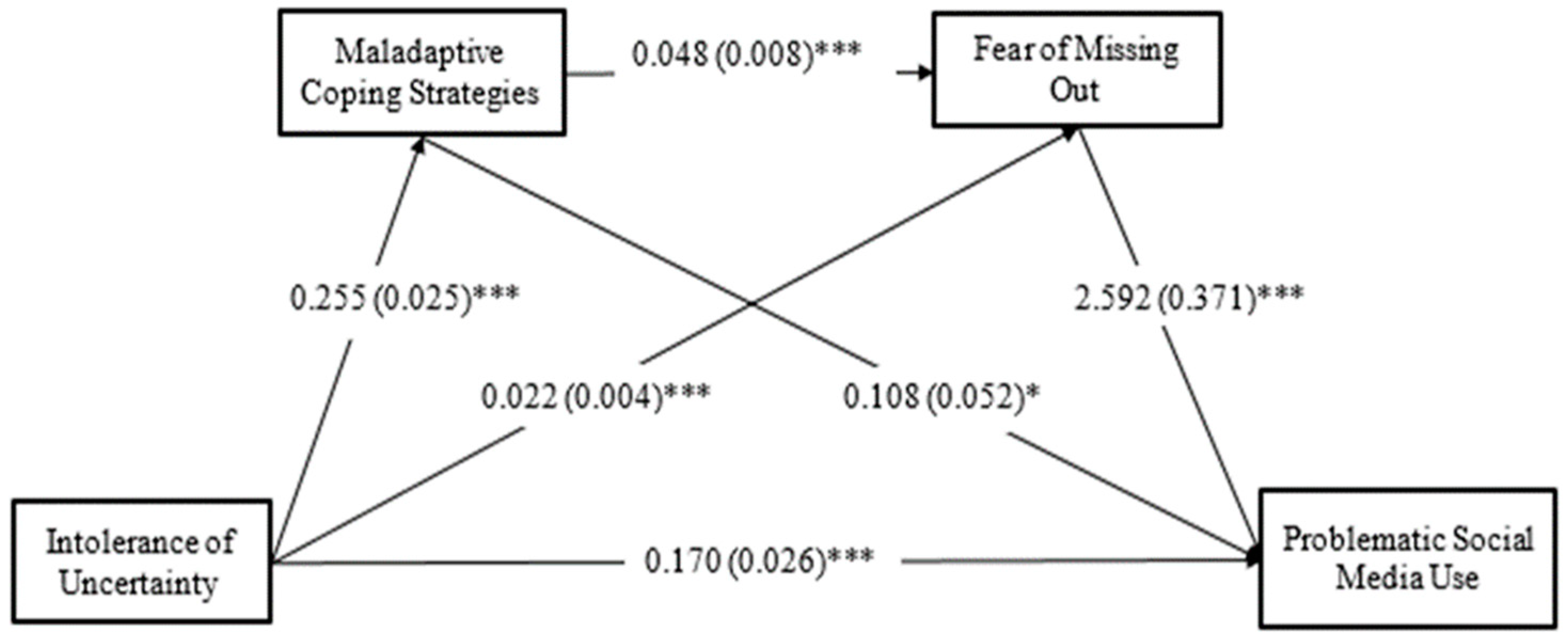

3.2. The Mediating Roles of Maladaptive Coping Strategies and Fear of Missing Out

3.3. Exploring the Serial Mediation Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goel, A.; Gupta, L. Social media in the times of COVID-19. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 26, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K. From social networks to publishing platforms: A review of the history and scholarship of academic social network sites. Front. Digit. Humanit. 2019, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, S.-F.; Chen, H.; Tisseverasinghe, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Butt, Z.A. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: A scoping review. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e175–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Ho, S.; Olusanya, O.; Antonini, M.V.; Lyness, D. The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2021, 22, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Z. Why some countries win and others loose from the COVID-19 pandemic? navigating the uncertainty. Eur. Res. Stud. 2021, 24, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Z. The strategy of vaccination and global pandemic: How framing may thrive on strategy during and after COVID-19. Eur. Res. Stud. 2021, 24, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Lee, D.S.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, R. Social media use, psychological well-being and physical health during lockdown. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Torsheim, T.; Brunborg, G.S.; Pallesen, S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.; Finkenauer, C.; Eijnden, R. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder-symptoms, social media use intensity, and social media use problems in adolescents: Investigating directionality. Child. Dev. 2020, 91, e853–e865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Cao, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Excessive social media use at work: Exploring the effects of social media overload on job performance. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Elhai, J.D.; Täht, K.; Vassil, K.; Levine, J.C.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Non-social smartphone use mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: Evidence from a repeated-measures study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.F.; Eaton, N.R. Transdiagnostic factors of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Mulvogue, M.K.; Thibodeau, M.A.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J. Increasingly certain about uncertainty: Intolerance of uncertainty across anxiety and depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N. Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.A.; King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Maladaptive coping styles in adolescents with internet gaming disorder symptoms. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 16, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Desgagné, G.; Krakauer, R.; Hong, R.Y. Increasing intolerance of uncertainty over time: The potential influence of increasing connectivity. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 48, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, G.; Gerritsen, L.; Duijndam, S.; Salemink, E.; Engelhard, I.M. Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19): Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercengiz, M.; Yildiz, B.; Savci, M.; Griffiths, M.D. Differentiation of self, emotion management skills, and nomophobia among smartphone users: The mediating and moderating roles of intolerance of uncertainty. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsido, A.N.; Arato, N.; Lang, A.; Labadi, B.; Stecina, D.; Bandi, S.A. The role of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and social anxiety in problematic smartphone and social media use. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 173, 110647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wolfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Muller, A.; Wolfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S. Stress: Appraisal and Coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1913–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Doruk, A.; Dugenci, M.; Ersoz, F.; Oznur, T. Intolerance of uncertainty and coping mechanisms in nonclinical young subjects. Nöro Psikiyatr. Arşivi 2015, 52, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.C.Y.; Shao, I.Y.T.; Liu, Y. This is not what I wanted. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loton, D.; Borkoles, E.; Lubman, D.; Polman, R. Video game addiction, engagement and symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety: The mediating role of coping. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2015, 14, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettie, H.; Daniels, J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.P. Avoidance/emotion-focused coping mediates the relationship between distress tolerance and problematic Internet use in a representative sample of adolescents in Taiwan: One-year follow-up. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, F.; Fioravanti, G.; Casale, S.; Boursier, V. The effects of the fear of missing out on people’s social networking sites use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of online relational closeness and individuals’ online communication attitude. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 620442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delongis, A.; Preece, M. Coping Skills. In Encyclopedia of Stress; Fink, G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; McAuliffe, C.; Keeley, H.; Perry, I.J.; Arensman, E. Mediating effects of coping style on associations between mental health factors and self-harm among adolescents. Crisis J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2013, 34, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Gallinari, E.F.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Yang, H. Depression, anxiety and fear of missing out as correlates of social, non-social and problematic smartphone use. Addict. Behav. 2020, 105, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Montag, C. Using machine learning to model problematic smartphone use severity: The significant role of fear of missing out. Addict. Behav. 2020, 103, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniewicz, C.A.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Elhai, J.D. Boredom proneness and fear of missing out mediate relations between depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use. Hum. Behav. Emerg. 2020, 2, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanello, A.W.; Gardner, F.L. The role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and worry. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2007, 31, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, P.J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, N.; Qian, M.; Jiang, Y.; Elhai, J.D. The influence of intolerance of uncertainty on anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese-speaking samples: Structure and validity of the Chinese translation of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 2021, 103, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.N.S.; Chan, C.S.; Ng, J.; Yip, C.-H. Action type-based factorial structure of Brief COPE among Hong Kong Chinese. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 38, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Dou, K. Validation and psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Fear of Missing Out Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Billieux, J.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mazzoni, E.; Pallesen, S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.H.; Strong, C.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.C.; Leung, H.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D. Time invariance of three ultra-brief internet-related instruments: Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS), Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS), and the nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale- Short Form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part B). Addict. Behav. 2020, 101, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Duan, W.; He, L. Peer relationship increasing the risk of social media addiction among Chinese adolescents who have negative emotions. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I.S. Social media addiction in romantic relationships: Does user’s age influence vulnerability to social media infidelity? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Han, X.; Yu, H.; Wu, Y.; Potenza, M.N. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinckrodt, B.; Abraham, W.T.; Wei, M.; Russell, D.W. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garami, J.; Haber, P.; Myers, C.E.; Allen, M.T.; Misiak, B.; Frydecka, D.; Moustafa, A.A. Intolerance of uncertainty in opioid dependency—Relationship with trait anxiety and impulsivity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Lyu, H. Future expectations and internet addiction among adolescents: The roles of intolerance of uncertainty and perceived social support. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 727106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Li, Q.; Meng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, X.; Dai, B.; Liu, X. The association between intolerance of uncertainty and Internet addiction during the second wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A multiple mediation model considering depression and risk perception. PsyCh. J. 2022, 11, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, K.; Hook, R.W.; Grant, J.E.; Czabanowska, K.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Chamberlain, S.R. Eating disorders with over-exercise: A cross-sectional analysis of the mediational role of problematic usage of the internet in young people. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 132, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, N.O.; Ivanova, E.; Knäuper, B. Differentiating intolerance of uncertainty from three related but distinct constructs. Anxiety Stress Coping 2014, 27, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Yang, G.; Li, B.; Deng, Q.; Guo, L. The impact of intolerance of uncertainty on test anxiety: Student athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luhmann, C.C.; Ishida, K.; Hajcak, G. Intolerance of uncertainty and decisions about delayed, probabilistic rewards. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, E.; DiMarco, I.D.; Hekler, E.B.; Mohlman, J.; Staples, A.M. Current theoretical models of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): Conceptual review and treatment implications. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, M.A.; Antwi, C.O.; Ntim, S.Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Ren, J. Am I gonna get a job? Graduating students’ psychological capital, coping styles, and employment anxiety. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M. Understanding the relationship between distress intolerance and problematic Internet use: The mediating role of coping motives and the moderating role of need frustration. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentes, E.L.; Ruscio, A.M. A meta-analysis of the relation of intolerance of uncertainty to symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, M.G.; Messner, G.R.; Marks, J.B. Intolerance of uncertainty as a factor linking obsessive-compulsive symptoms, health anxiety and concerns about the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2021, 28, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korte, C.; Friedberg, R.D.; Wilgenbusch, T.; Paternostro, J.K.; Brown, K.; Kakolu, A.; Tiller-Ormord, J.; Baweja, R.; Cassar, M.; Barnowski, A. Intolerance of uncertainty and health-related anxiety in youth amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding and weathering the continuing storm. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. 2021, 29, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Li, C.; Meng, C.; Guo, X.; Lv, J.; Fei, J.; Mei, S. Psychological distress and internet addiction following the COVID-19 outbreak: Fear of missing out and boredom proneness as mediators. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 40, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacher, H.; Rudolph, C.W. Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lábadi, B.; Arató, N.; Budai, T.; Inhóf, O.; Stecina, D.T.; Sík, A.; Zsidó, A.N. Psychological well-being and coping strategies of elderly people during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary. Aging. Ment. Health 2022, 26, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J.; Tadros, N.; Khalaf, T.; Ego, V.; Eisenbeck, N.; Carreno, D.F.; Nassar, E. Trait emotional intelligence and wellbeing during the pandemic: The mediating role of meaning-centered coping. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D. Students’ wellbeing, fear of missing out, and social media engagement for leisure in higher education learning environments. Curr. Psychol. 2016, 37, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, P.; Mikaeili, N.; Ghaseminejad, M.A.; Kazemi, Z.; Pourdonya, M. Social anxiety and benign and toxic online self-disclosures: An investigation into the role of rejection sensitivity, self-regulation, and internet addiction in college students. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augner, C.; Vlasak, T.; Aichhorn, W.; Barth, A. Tackling the ‘digital pandemic’: The effectiveness of psychological intervention strategies in problematic Internet and smartphone use-A meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 56, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriss, J.; Wake, S.; Elizabeth, C.; Van Reekum, C.M. I doubt it is safe: A meta-analysis of self-reported intolerance of uncertainty and threat extinction training. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2021, 1, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, A.; Williams, D. Why people use social media: A uses and gratifications approach. Qual. Mark. Res. 2013, 16, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishel, M.H.; Germino, B.B.; Gil, K.M.; Belyea, M.; Laney, I.C.; Stewart, J.; Porter, L.; Clayton, M. Benefits from an uncertainty management intervention for African–American and Caucasian older long-term breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2005, 14, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.P.; Barber, L.K. Addressing FoMO and telepressure among university students: Could a technology intervention help with social media use and sleep disruption? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, Z.; Drozdowski, G.; Panait, M. Understanding the impact of Generation Z on risk management—A preliminary views on values, competencies, and ethics of the Generation Z in public administration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Intolerance of Uncertainty | Maladaptive Coping Strategies | Fear of Missing Out | Problematic Social Media Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Intolerance of Uncertainty | 1 | |||

| 2 | Maladaptive Coping Strategies | 0.516 *** | 1 | ||

| 3 | Fear of Missing Out | 0.489 *** | 0.507 *** | 1 | |

| 4 | Problematic Social Media Use | 0.566 *** | 0.462 *** | 0.581 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 35.72 | 14.49 | 3.31 | 19.12 | |

| SD | 11.27 | 5.70 | 0.789 | 5.66 | |

| Skewness | −0.088 | −0.079 | −0.600 | −0.351 | |

| Kurtosis | −1.041 | −0.482 | −0.047 | −0.508 |

| Model Pathways | Effect | 95% Boot CI |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Path | ||

| IU → PSMU | 0.226 | [0.174, 0.279] |

| Indirect Path | ||

| IU → Maladaptive Coping Strategies → PSMU | 0.059 | [0.030, 0.095] |

| Direct Path | ||

| IU → PSMU | 0.188 | [0.140, 0.237] |

| Indirect Path | ||

| IU → Fear of Missing Out → PSMU | 0.097 | [0.058, 0.143] |

| Model Pathways | Effect | 95% Boot CI |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Path | ||

| IU → PSMU | 0.170 | [0.118, 0.221] |

| Indirect Path | ||

| Total: IU → PSMU | 0.116 | [0.070, 0.168] |

| IU → Maladaptive Coping Strategies → PSMU | 0.028 | [0.002, 0.059] |

| IU → Fear of Missing Out → PSMU | 0.057 | [0.025, 0.095] |

| IU → Maladaptive Coping Strategies → Fear of Missing Out → PSMU | 0.032 | [0.015, 0.054] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Li, Y.; Kwok, S.Y.C.L.; Mu, W. The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Serial Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214924

Sun C, Li Y, Kwok SYCL, Mu W. The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214924

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chaoran, Yumei Li, Sylvia Y. C. L. Kwok, and Wenlong Mu. 2022. "The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Serial Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214924

APA StyleSun, C., Li, Y., Kwok, S. Y. C. L., & Mu, W. (2022). The Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Social Media Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Serial Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214924