The Chinese Mandarin Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Evaluation of Linguistic and Content Validity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

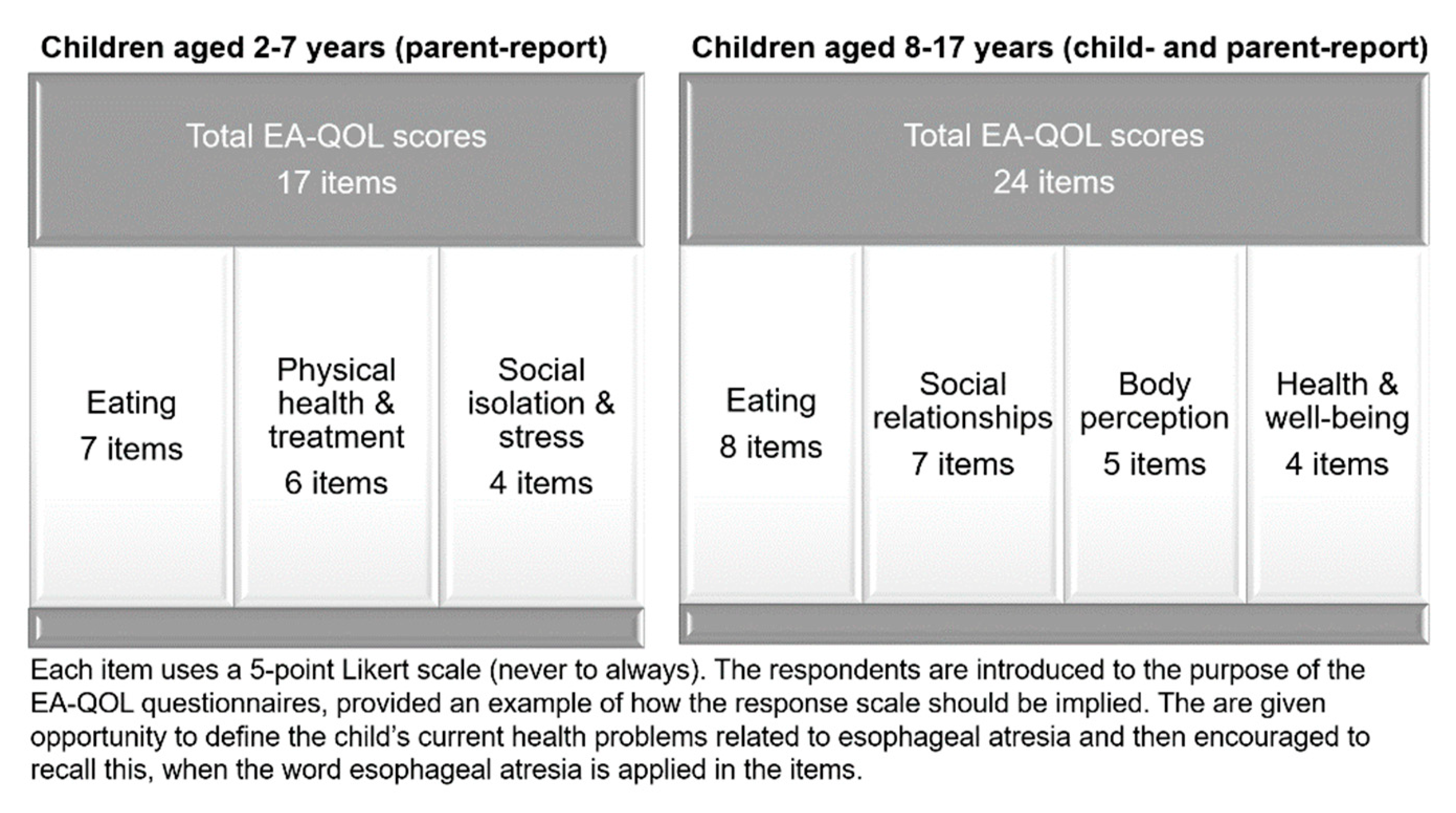

2.1. The EA-QOL Questionnaires

2.2. Framework

2.3. Preparation—Step 1

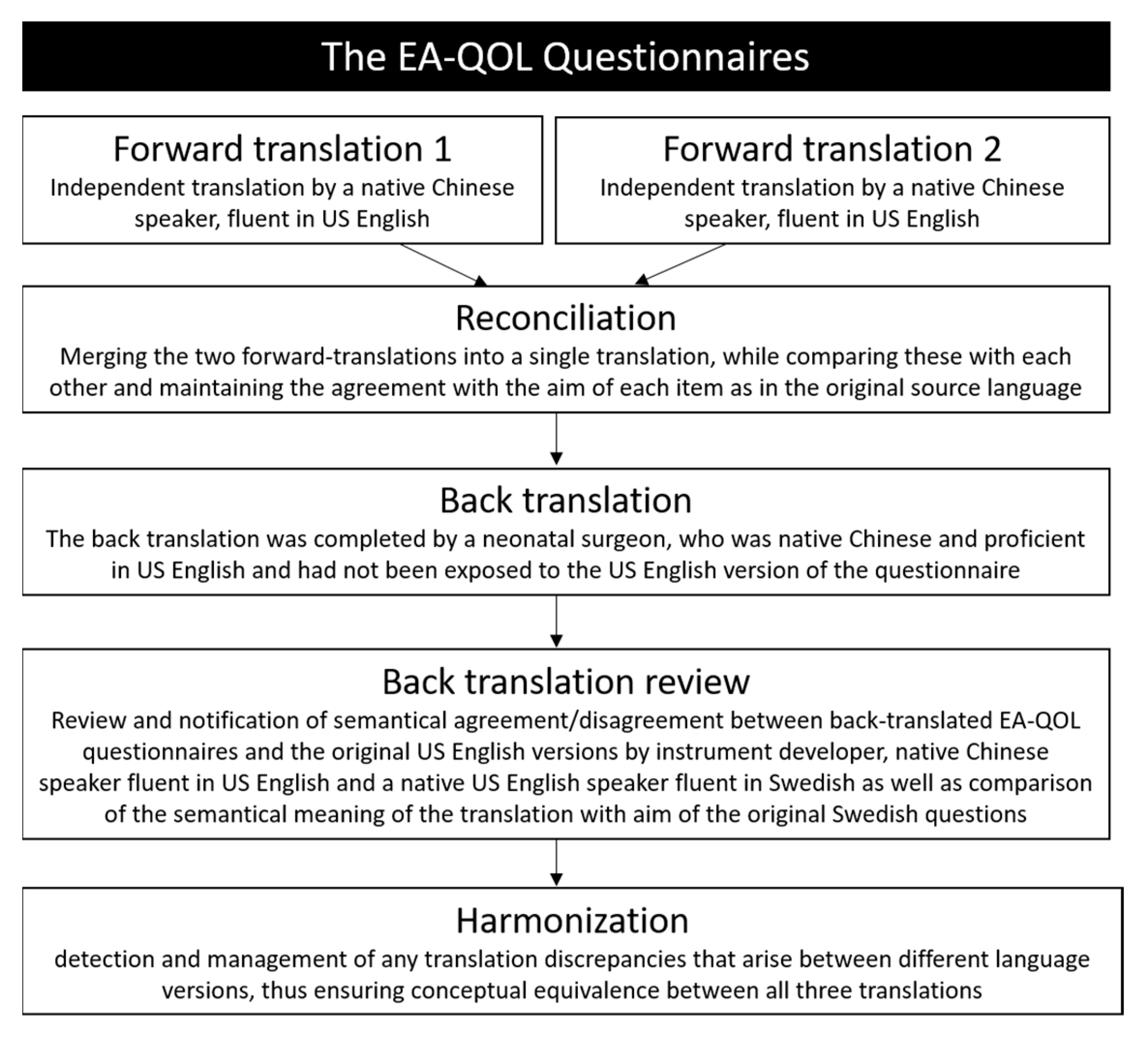

2.4. Translation—Step 2–6

2.5. Cognitive Debriefing—Step 7

2.6. Review of Cognitive Debriefing Results—Step 8

2.7. Finalization—Step 9

2.8. Proof-Reading and Final Results—Step 10

3. Results

3.1. Translation—Step 2–6

3.2. Cognitive Debriefing—Step 7

3.3. Review of Cognitive Debriefing Results—Step 8

- One item of the EA-QOL questionnaire for children with EA aged 2–7 (no 1, regarding impact on the child’s eating due to food sticking in the throat) and for children aged 8–17 years, respectively (no 1, regarding impact on the child’s eating due to food getting stuck in the throat), both include the expression “food gets stuck in the throat”, which were literally translated as “食物卡在喉咙里” in Chinese Mandarin language. However, most participants stated that food often gets stuck in the esophagus, not the throat. Since “food gets stuck in the throat” was an idiomatic expression, the final Chinese Mandarin translation was adjusted to “食物卡在食管里”.

- The term “choke” has two meanings in Chinese Mandarin language, namely “food gets stuck in the esophagus and compresses the airway, preventing the child from breathing normally (窒息)” and “cough caused by inhalation of food into the trachea while eating (呛咳)”. The word “choke” is used in one item of the EA-QOL questionnaire for children aged 2–7 years (no 5, regarding the child’s experiences of worry when choking on food) and two items of the EA-QOL questionnaire for children aged 8–17 years (no 5 regarding the child’s feelings of fear when choking during eating, and no 6 regarding the child’s difficulties to eat a meal due to choking experiences). Since most participants recognized the second situation and this maintained the conceptual equivalence, we retained this wording.

- In one item of the EA-QOL questionnaire for children aged 2–7 years (no 7, regarding limitations of social activities and events which include eating with peers), parents are asked about their child’s experience of having problems to eat food at a party or when he/she is out with friends. Few parents in the cognitive debriefing would let their child go to parties or eat with friends, because their child’s food needs to be prepared by themselves. This would make it unfeasible for parents of children who have not dined outside home to reply to this item. It was therefore adjusted in wording to increase clarity in a Chinese setting, to ask about problems for the child to attend parties or being out with friends due to eating difficulties. The final Chinese Mandarin translation was adjusted to “您的孩子参加聚会或与朋友外出吃饭时是否有问题”.

3.4. Finalization—Step 9

3.5. Final Review and Final Report—Step 10

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Lennep, M.; Singendonk, M.M.J.; Dall’Oglio, L.; Gottrand, F.; Krishnan, U.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.W.J.; Omari, T.I.; Benninga, M.A.; van Wijk, M.P. Oesophageal atresia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tashiro, J.; Allan, B.J.; Sola, J.E.; Parikh, P.P.; Hogan, A.R.; Neville, H.L.; Perez, E.A. A nationwide analysis of clinical outcomes among newborns with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistulas in the United States. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 190, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulkowski, J.P.; Cooper, J.N.; Lopez, J.J.; Jadcherla, Y.; Cuenot, A.; Mattei, P.; Deans, K.J.; Minneci, P.C. Morbidity and mortality in patients with esophageal atresia. Surgery 2014, 156, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liao, J.; Li, S.; Hua, K.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, J. Risk Factors and Reasons for Treatment Abandonment for Patients With Esophageal Atresia: A Study From a Tertiary Care Hospital in Beijing, China. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 634573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyken, W.; Orley, J.; Power, M.; Herrman, H.; Vandam, F. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL)—Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, S.; Blömeke, J.; Bullinger, M.; Dingemann, J.; Quitmann, J. Basic Principles of Health-Related Quality of Life in Parents and Caregivers of Pediatric Surgical Patients with Rare Congenital Malformations—A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 30, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverman, L.; Limperg, P.F.; Young, N.L.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Klaassen, R.J. Paediatric health-related quality of life: What is it and why should we measure it? Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmil, L.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Herdman, M. Quality of life and rare diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 686, 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Matza, L.S.; Patrick, D.L.; Riley, A.W.; Alexander, J.J.; Rajmil, L.; Pleil, A.M.; Bullinger, M. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: Report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health 2013, 16, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Quitmann, J.; Dingemann, C. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients after Repair of Esophageal Atresia: A Review of Current Literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 30, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan Tanny, S.P.; Comella, A.; Hutson, J.M.; Omari, T.I.; Teague, W.J.; King, S.K. Quality of life assessment in esophageal atresia patients: A systematic review focusing on long-gap esophageal atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 2473–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Chaplin, J.E.; Gatzinsky, V.; Jönsson, L.; Abrahamson, K. Health-related quality of life among children, young people and adults with esophageal atresia: A review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 2433–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flieder, S.; Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Witt, S.; Dingemann, C.; Quitmann, J.H.; Jönsson, L.; Gatzinsky, V.; Chaplin, J.E.; Dammeier, B.G.; Bullinger, M.; et al. Generic Health-Related Quality of Life after Repair of Esophageal Atresia and Its Determinants within a German-Swedish Cohort. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 29, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Knezevich, M.; Lingongo, M.; Szabo, A.; Yin, Z.; Oldham, K.T.; Calkins, C.M.; Sato, T.T.; Arca, M.J. Long-term Quality of Life in Neonatal Surgical Disease. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, C.; Michaud, L.; Salleron, J.; Neut, D.; Sfeir, R.; Thumerelle, C.; Bonnevalle, M.; Turck, D.; Gottrand, F. Long-term outcome of children with oesophageal atresia type III. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeytre, C.; De Lagausie, P.; Merrot, T.; Baumstarck, K.; Oudyi, M.; Dubus, J.C. Medium-term outcome, follow-up, and quality of life in children treated for type III esophageal atresia. Arch. Pediatr. 2013, 20, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Dingemann, J.; Witt, S.; Quitmann, J.H.; Jönsson, L.; Gatzinsky, V.; Chaplin, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Flieder, S.; Ure, B.M.; et al. The Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-life Questionnaires: Feasibility, Validity and Reliability in Sweden and Germany. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Abrahamsson, K.; Quitmann, J.H.; Sommer, R.; Witt, S.; Dingemann, J.; Flieder, S.; Jönsson, L.; Gatzinsky, V.; Bullinger, M.; et al. Development and pilot-testing of a condition-specific instrument to assess the quality-of-life in children and adolescents born with esophageal atresia. Dis. Esophagus 2017, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Chaplin, J.E.; Gatzinsky, V.; Jönsson, L.; Wigert, H.; Apell, J.; Sillén, U.; Abrahamsson, K. Health-related quality of life experiences among children and adolescents born with esophageal atresia: Development of a condition-specific questionnaire for pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 51, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, T.; Arslan, U.E.; Ulukaya Durakbaşa, Ç.; Aydöner, S.; Boybeyi-Türer, Ö.; Quitmann, J.H.; Dingemann, J.; Dellenmark-Blom, M. Feasibility, Reliability, and Validity of the Turkish Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires to Assess Condition-Specific Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents Born with Esophageal Atresia. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 32, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozensztrauch, A.; Śmigiel, R.; Patkowski, D.; Gerus, S.; Kłaniewska, M.; Quitmann, J.H.; Dellenmark-Blom, M. Reliability and Validity of the Polish Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires to Assess Condition-Specific Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents Born with Esophageal Atresia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Kate, C.A.; IJsselstijn, H.; Dellenmark-Blom, M.; van Tuyll van Serooskerken, E.S.; Joosten, M.; Wijnen, R.M.H.; van Wijk, M.P.; On Behalf of the Dcea Study Group. Psychometric Performance of a Condition-Specific Quality-of-Life Instrument for Dutch Children Born with Esophageal Atresia. Children 2022, 9, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Song, N.; Zhu, G.; Wang, B.; Qin, M.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese mandarin version of PedsQL™ 3.0 transplant module. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.H.; Wu, F.Q.; Li, Y.; Lai, J.M.; Su, G.X.; Cui, S.H.; Chen, Z.; Li, H. The quality of life in Chinese juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients: Psychometric properties of the pediatric quality of life inventor generic core scales and rheumatology module. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-B.; Jin, Y.-X.; Wu, Y.-H.; Hou, Z.-K.; Chen, X.-L. Translation and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014, 59, 390–420. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X.; Osman, A.M.Y.; Pompili, C.; Koller, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ge, J.; et al. Translation and adaptation of the EORTC QLQ-LC 29 for use in Chinese patients with lung cancer. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2021, 5, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alelayan, H.; Liang, L.; Ye, R.; Meng, J.; Liao, X. Assessing health-related quality of life in Chinese children and adolescents with cancer: Validation of the DISABKIDS chronic generic module (DCGM-37). BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, L.; Hong, S.; Cheng, L.; Kong, M.; Ye, Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Pediatric Quality Of Life InventoryTM (PedsQLTM) 3.0 neuromuscular module in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xie, L.; Shang, S.; Dong, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Han, F. Narcolepsy Quality-of-Life Instrument with 21 Questions: A Translation and Validation Study in Chinese Pediatric Narcoleptics. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2021, 13, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMuro, C.J.; Lewis, S.A.; DiBenedetti, D.B.; Price, M.A.; Fehnel, S.E. Successful implementation of cognitive interviews in special populations. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, H. The value of WeChat application in chronic diseases management in China. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 196, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, D.L.; Burke, L.B.; Gwaltney, C.J.; Leidy, N.K.; Martin, M.L.; Molsen, E.; Ring, L. Content validity—Establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: Part 1—Eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011, 14, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, A.; Isa, F.; Kyte, D.; Pankhurst, T.; Kerecuk, L.; Ferguson, J.; Lipkin, G.; Calvert, M. Patient reported outcome measures in rare diseases: A narrative review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, V.E.; Klaassen, R.J.; Bolton-Maggs, P.H.; Grainger, J.D.; Curtis, C.; Wakefield, C.; Dufort, G.; Riedlinger, A.; Soltner, C.; Blanchette, V.S.; et al. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in rare populations: A practical approach to cross-cultural translation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, K.; Vernon, M.K.; Patrick, D.L.; Perfetto, E.; Nestler-Parr, S.; Burke, L. Patient-Reported Outcome and Observer-Reported Outcome Assessment in Rare Disease Clinical Trials: An ISPOR COA Emerging Good Practices Task Force Report. Value Health 2017, 20, 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, D.L.; Burke, L.B.; Gwaltney, C.J.; Leidy, N.K.; Martin, M.L.; Molsen, E.; Ring, L. Content validity—Establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: Part 2—Assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011, 14, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, C.; Huus, K.; Åkesson, K.; Enskär, K. Children’s experiences about a structured assessment of health-related quality of life during a patient encounter. Child. Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, V.; Detmar, S.; Koopman, H.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Caron, H.; Hoogerbrugge, P.; Egeler, R.M.; Kaspers, G.; Grootenhuis, M. Reporting health-related quality of life scores to physicians during routine follow-up visits of pediatric oncology patients: Is it effective? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 5, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, C.; Varni, J.W. Health-related quality of life and symptom reporting: Similarities and differences between children and their parents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2013, 172, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Characteristics of the Patient | |

|---|---|

| Severe | Clinically significant dysphagia |

| Clinically significant gastro-esophageal reflux disease | |

| Received dilatation of esophagus | |

| Airway disease | |

| Clinical significant associated anomaly | |

| Moderate | Clinically significant dysphagia, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, received dilatation of esophagus |

| OR | |

| Clinically significant airway disease | |

| With associated anomaly | |

| Mild | Dysphagia OR gastroesophageal reflux disease OR airway disease |

| No associated anomaly |

| The EA-QOL Questionnaires | Total Number of Items | Number of Items with Conceptual Agreement | Number of Items with Conceptual Inconsistences | Need for Minor Revisions in the Chinese Translation after Discussion in the Research Team | Minor Revisions in the Chinese Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children aged 2–7 (parent report) | |||||

| Eating | 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 | “difficulty swallowing food” was changed to “difficulty to eat” “a regular meal” was changed to “a full meal” Removed extra examples in two items |

| Physical health & treatment | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | “high respiratory infections”—“high” was omitted |

| Social isolation & stress | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Item wording of school absence modified |

| Children aged 8–17 (child report/parent report) | |||||

| Eating | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 | |

| Social relationship | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | Do you “think” was corrected to “feel” in an item asking about feelings about the child feeling like the only one with esophageal atresia |

| Body perception | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Health and well-being | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | Item wording was shortened from, esophageal atresia makes me “sad or upset” to using only “sad” |

| Children Aged 2–7 (n = 8) | Children Aged 8–17 Years (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Child background information | ||

| Male (n, %) | 6 (66.7) | 5 (83.3) |

| Gestational age (median and P25/P75, weeks) | 37.2 (37.0, 38.2) | 37 (37.0, 39.7) |

| Birth weight (median and P25/P75, grams) | 2600 (2275, 3003) | 3100 (2375, 3200) |

| Primary esophageal repair (n, %) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (83.3) |

| Revisional surgery (n, %) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Associated anomalies (n, %) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Child age (median and P25/P75, year) | 3 (2.3, 4.5) | 9.5 (8, 11.5) |

| Parental information | ||

| Mother (n, %) | 8 (100.0) | 3 (50.0) |

| Parental age (median and P25/P75, year) | 33.0 (33.0, 36.0) | 39.5 (37.8, 46.5) |

| Cohabitant partner (n, %) | 8 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) |

| College/University educated (n, %) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Dellenmark-Blom, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Quitmann, J.H.; Huang, J. The Chinese Mandarin Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Evaluation of Linguistic and Content Validity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214923

Li S, Dellenmark-Blom M, Zhao Y, Gu Y, Li S, Yang S, Quitmann JH, Huang J. The Chinese Mandarin Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Evaluation of Linguistic and Content Validity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214923

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Siqi, Michaela Dellenmark-Blom, Yong Zhao, Yichao Gu, Shuangshuang Li, Shen Yang, Julia H. Quitmann, and Jinshi Huang. 2022. "The Chinese Mandarin Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Evaluation of Linguistic and Content Validity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214923

APA StyleLi, S., Dellenmark-Blom, M., Zhao, Y., Gu, Y., Li, S., Yang, S., Quitmann, J. H., & Huang, J. (2022). The Chinese Mandarin Version of the Esophageal-Atresia-Quality-of-Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents: Evaluation of Linguistic and Content Validity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214923