The Application of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model to Gambling Urge and Involvement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Gambling

1.2. The Roles of Emotion Regulation Difficulties

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Intolerance of Uncertainty

2.2.2. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation

2.2.3. Gambling Urge

2.2.4. Gambling Involvement

2.2.5. Demographics

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Hypothesis Testing (H1 to H5) by Correlation Analysis

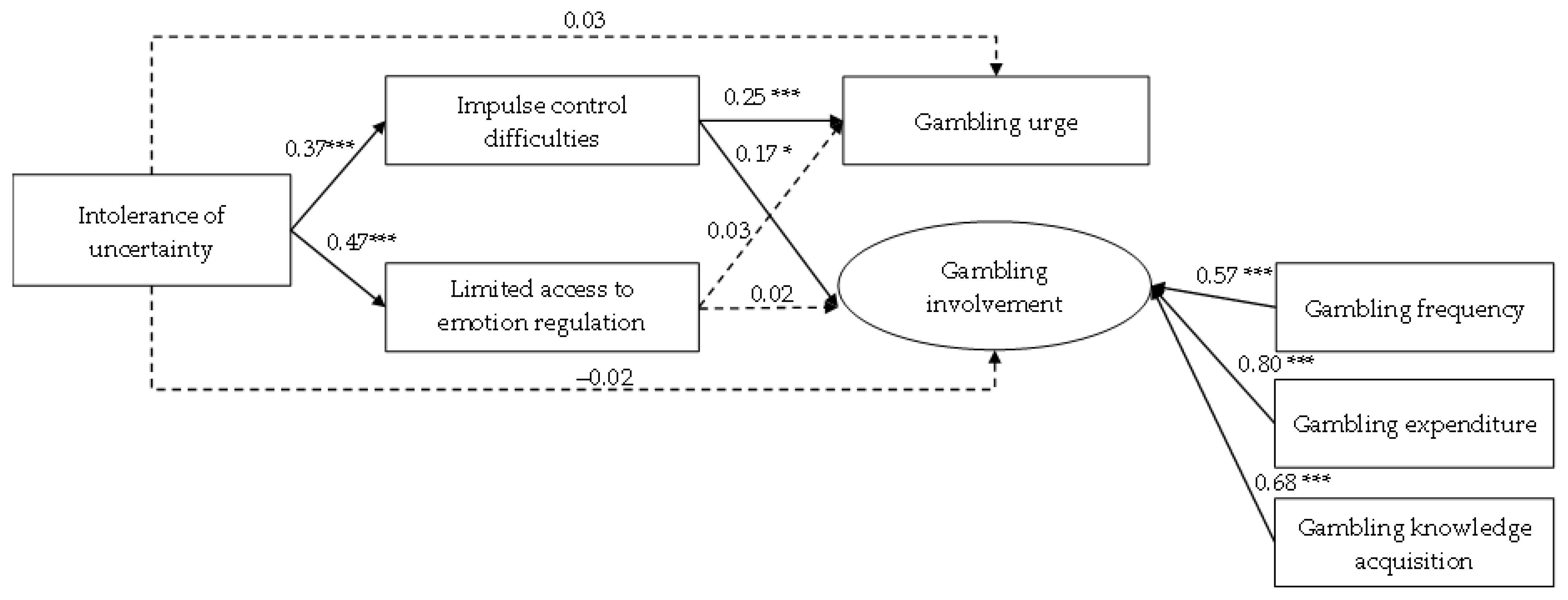

3.3. Hypothesis Testing (H6 and H7) by Path Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; The American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calado, F.; Griffiths, M.D. Problem Gambling Worldwide: An Update and Systematic Review of Empirical Research (2000–2015). J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.M.S.; Lau, J.T.F. Gambling in China: Socio-Historical Evolution and Current Challenges: Gambling in China. Addiction 2015, 110, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. Announcement of the Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China No. 26, 2022. Available online: http://zhs.mof.gov.cn/zhengcefabu/202208/t20220831_3837398.htm (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Abbott, M.W. Gambling and Gambling-Related Harm: Recent World Health Organization Initiatives. Public Health 2020, 184, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugas, M.J.; Gagnon, F.; Ladouceur, R.; Freeston, M.H. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Preliminary Test of a Conceptual Model. Behav. Res. Ther. 1998, 36, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Norton, M.A.P.J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Fearing the Unknown: A Short Version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.D.; Kessel, E.M.; Jackson, F.; Hajcak, G. The Impact of an Unpredictable Context and Intolerance of Uncertainty on the Electrocortical Response to Monetary Gains and Losses. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 16, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carleton, R.N.; Mulvogue, M.K.; Thibodeau, M.A.; McCabe, R.E.; Antony, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Increasingly Certain about Uncertainty: Intolerance of Uncertainty across Anxiety and Depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, A.E.J.; McEvoy, P.M. A Transdiagnostic Examination of Intolerance of Uncertainty Across Anxiety and Depressive Disorders. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2012, 41, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihata, S.; McEvoy, P.M.; Mullan, B.A.; Carleton, R.N. Intolerance of Uncertainty in Emotional Disorders: What Uncertainties Remain? J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 41, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, C.; Langlois, F.; Provencher, M.D.; Gosselin, P. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Difficulties in Emotion Regulation: Proposal for an Integrative Model of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 69, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, M.J.; Gosselin, P.; Ladouceur, R. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Worry: Investigating Specificity in a Nonclinical Sample. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2001, 25, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, M.J.; Hedayati, M.; Karavidas, A.; Buhr, K.; Francis, K.; Phillips, N.A. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Information Processing: Evidence of Biased Recall and Interpretations. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2005, 29, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Ghisi, M.; Carraro, E.; Barclay, N.; Payne, R.; Freeston, M.H. Revising the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Evidence from UK and Italian Undergraduate Samples. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, D.F.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Brigidi, B.D.; Foa, E.B. Intolerance of Uncertainty in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszczynski, A.; Nower, L. A Pathways Model of Problem and Pathological Gambling: Pathways Model of Gambling. Addiction 2002, 97, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.T.A.; Griffiths, M.D. A Qualitative Investigation of Problem Gambling as an Escape-Based Coping Strategy. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2007, 80, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornilov, S.A.; Krasnov, E.; Kornilova, T.V.; Chumakova, M.A. Individual Differences in Performance on Iowa Gambling Task Are Predicted by Tolerance and Intolerance for Uncertainty. EAPCogSci 2015, 728–731. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, C.C.; Ishida, K.; Hajcak, G. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Decisions About Delayed, Probabilistic Rewards. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Li, Q.; Meng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, X.; Dai, B.; Liu, X. The Association between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Internet Addiction during the Second Wave of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Multiple Mediation Model Considering Depression and Risk Perception. PsyCh J. 2022, 11, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D.; Elhai, J.D.; Täht, K.; Vassil, K.; Levine, J.C.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Non-Social Smartphone Use Mediates the Relationship between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Smartphone Use: Evidence from a Repeated-Measures Study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 96, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raylu, N.; Oei, T.P.S. The Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS): Development, Confirmatory Factor Validation and Psychometric Properties. Addiction 2004, 99, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugas, M.J.; Buhr, K.; Ladouceur, R. The Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty in Etiology and Maintenance. In Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice; Heimberg, R.G., Turk, C.L., Mennin, D.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, P.; Ladouceur, R.; Pelletier, O. Évaluation de l’attitude d’un Individu Face Aux Différents Problèmes de Vie: Le Questionnaire d’attitude Face Aux Problèmes (QAP). J. Thérapie Comport. Cogn. 2005, 15, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Tesini, V.; Cerea, S.; Ghisi, M. Are Difficulties in Emotion Regulation and Intolerance of Uncertainty Related to Negative Affect in Borderline Personality Disorder? Clin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Ghisi, M.; Caggiu, I.; Lauriola, M. How Is Intolerance of Uncertainty Related to Negative Affect in Individuals with Substance Use Disorders? The Role of the Inability to Control Behaviors When Experiencing Emotional Distress. Addict. Behav. 2021, 115, 106785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, K.; Taylor, A.J.G. Investigating How Intolerance of Uncertainty and Emotion Regulation Predict Experiential Avoidance in Non-Clinical Participants. Psychol. Stud. 2021, 66, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.; Frey, B.N.; Green, S.M. Validation of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale as a Screening Tool for Perinatal Anxiety. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Carraro, E.; Martignon, A.; Cerea, S.; Ghisi, M. “I’m Uncertain: What Should I Do?”: An Investigation of Behavioral Responses to Everyday Life Uncertain Situations. J. Cogn. Ther. 2019, 12, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, R.; Robinson, L.; Honey, E.; Freeston, M. ‘We Know Intolerance of Uncertainty Is a Transdiagnostic Factor but We Don’t Know What It Looks like in Everyday Life’: A Systematic Review of Intolerance of Uncertainty Behaviours. In Clinical Psychology Forum; Newcastle University: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017; Available online: https://shop.bps.org.uk/clinical-psychology-forum-no-296-august-2017 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Bomyea, J.; Ramsawh, H.; Ball, T.M.; Taylor, C.T.; Paulus, M.P.; Lang, A.J.; Stein, M.B. Intolerance of Uncertainty as a Mediator of Reductions in Worry in a Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Program for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 33, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriss, J.; McSorley, E. Intolerance of Uncertainty Is Associated with Reduced Attentional Inhibition in the Absence of Direct Threat. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.R.; Fergus, T.A.; Wu, K.D. The Interactive Effect of Worry and Intolerance of Uncertainty on Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2013, 37, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, S.; Gregory, D.F.; Stasiak, J.; Mitchell, W.J.; Helion, C.; Murty, V.P. Influence of Naturalistic, Emotional Context and Intolerance of Uncertainty on Arousal-Mediated Biases in Episodic Memory. PsyArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, M.; Nigro, G.; D’Olimpio, F.; Griffiths, M.D.; Cosenza, M. Mentalizing Failures, Emotional Dysregulation, and Cognitive Distortions Among Adolescent Problem Gamblers. J. Gambl. Stud. 2021, 37, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, P.; Estévez, A.; Urbiola, I. Pathological Gambling and Associated Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Emotion Regulation, and Anxious-Depressive Symptomatology. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurm, A.; Satel, J.; Montag, C.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pontes, H.M. The Relationship between Gambling Disorder, Stressful Life Events, Gambling-Related Cognitive Distortions, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation, and Self-Control. J. Gambl. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.D.; Grisham, J.R.; Erskine, A.; Cassedy, E. Deficits in Emotion Regulation Associated with Pathological Gambling: Gambling and Emotion Regulation. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 51, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Wu, A.M.S.; Tong, K. Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of the Inventory of Gambling Motives, Attitudes and Behaviors among Chinese Adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2015, 13, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shead, N.W.; Callan, M.J.; Hodgins, D.C. Probability Discounting among Gamblers: Differences across Problem Gambling Severity and Affect-Regulation Expectancies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.M.S.; Tao, V.Y.K.; Tong, K.; Cheung, S.F. Psychometric Evaluation of the Inventory of Gambling Motives, Attitudes and Behaviours (GMAB) among Chinese Gamblers. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2012, 12, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.H.C.; Wu, A.M.S.; Tong, K.K. Validation of the Gambling Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Chinese Undergraduate Students. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 31, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, P.; Estevez, A. Predictive Role of Attachment, Coping, and Emotion Regulation in Gambling Motives of Adolescents and Young People. J. Gambl. Stud. 2020, 36, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeston, M.H.; Rhéaume, J.; Letarte, H.; Dugas, M.J.; Ladouceur, R. Why Do People Worry? Personal. Individ. Differ. 1994, 17, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Psychometric Properties of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS) in a Chinese-Speaking Population. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2013, 41, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, L.; Wu, Q.; Le, H.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Ma, G.; Tao, H. COVID-19-Related Intolerance of Uncertainty and Mental Health among Back-To-School Students in Wuhan: The Moderation Effect of Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Du, W.; Li, Z. Test of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale in Chinese People. China J. Health Psychol. 2007, 15, 336–340. [Google Scholar]

- Oei, T.P.S.; Lin, J.; Raylu, N. Validation of the Chinese Version of the Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS-C). J. Gambl. Stud. 2007, 23, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovenko, I.; Hodgins, D.C.; el-Guebaly, N.; Casey, D.M.; Currie, S.R.; Smith, G.J.; Williams, R.J.; Schopflocher, D.P. Cognitive Distortions Predict Future Gambling Involvement. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 16, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, V.Y.K.; Wu, A.M.S.; Cheung, S.F.; Tong, K.K. Development of an Indigenous Inventory GMAB (Gambling Motives, Attitudes and Behaviors) for Chinese Gamblers: An Exploratory Study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2011, 27, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- Enders, C.; Bandalos, D. The Relative Performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation for Missing Data in Structural Equation Models. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2001, 8, 430–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, K.M.; McLeish, A.C.; O’Bryan, E.M. The Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty in Terms of Alcohol Use Motives among College Students. Addict. Behav. 2015, 42, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglesby, M.E.; Albanese, B.J.; Chavarria, J.; Schmidt, N.B. Intolerance of Uncertainty in Relation to Motives for Alcohol Use. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2015, 39, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, S.; Barrault, S.; Brunault, P.; Varescon, I. The Role of Gambling Type on Gambling Motives, Cognitive Distortions, and Gambling Severity in Gamblers Recruited Online. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, B.J.I.; McGrath, D.S.; Dechant, K. The Gambling Motives Questionnaire Financial: Factor Structure, Measurement Invariance, and Relationships with Gambling Behaviour. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radkovsky, A.; McArdle, J.J.; Bockting, C.L.H.; Berking, M. Successful Emotion Regulation Skills Application Predicts Subsequent Reduction of Symptom Severity during Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan-Glauser, E.S.; Scherer, K.R. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): Factor Structure and Consistency of a French Translation. Swiss J. Psychol. 2013, 72, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchica, L.A.; Mills, D.J.; Keough, M.T.; Montreuil, T.C.; Derevensky, J.L. Emotion Regulation in Emerging Adult Gamblers and Its Mediating Role with Depressive Symptomology. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 258, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Su, X.; Wu, A.M.S. Is Fast Life History Strategy Associated with Poorer Self-Regulation and Higher Vulnerability to Behavioral Addictions? A Cross-Sectional Study on Smartphone Addiction and Gaming Disorder. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intolerance of uncertainty | 34.41 | 6.94 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Impulse control difficulties | 13.55 | 3.89 | 0.37 *** | -- | ||||||

| 3. Limited access to emotion regulation strategies | 19.38 | 5.32 | 0.47 *** | 0.74 *** | -- | |||||

| 4. Gambling urge | 13.52 | 7.19 | 0.11 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.21 *** | -- | ||||

| 5. Gambling frequency | 2.56 | 0.79 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.30 *** | -- | |||

| 6. Gambling expenditure | 1.44 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.21 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.44 *** | 0.38 *** | -- | ||

| 7. Gambling knowledge acquisition | 1.74 | 0.87 | 0.06 | 0.15 *** | 0.10 * | 0.45 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.53 *** | -- | |

| 8. Age | 34.07 | 13.36 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.29 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.28 *** | -- |

| 9. Gender # | -- | -- | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.21 *** | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.16 *** | −0.34 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, H.; Hung, E.P.W.; Xie, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, A.M.S. The Application of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model to Gambling Urge and Involvement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214738

Zhou H, Hung EPW, Xie L, Yuan Z, Wu AMS. The Application of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model to Gambling Urge and Involvement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):14738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214738

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Hui, Eva P. W. Hung, Li Xie, Zhen Yuan, and Anise M. S. Wu. 2022. "The Application of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model to Gambling Urge and Involvement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 22: 14738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214738

APA StyleZhou, H., Hung, E. P. W., Xie, L., Yuan, Z., & Wu, A. M. S. (2022). The Application of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Model to Gambling Urge and Involvement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214738