Reasons for Turnover of Kansas Public Health Officials during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Demographics of Participants

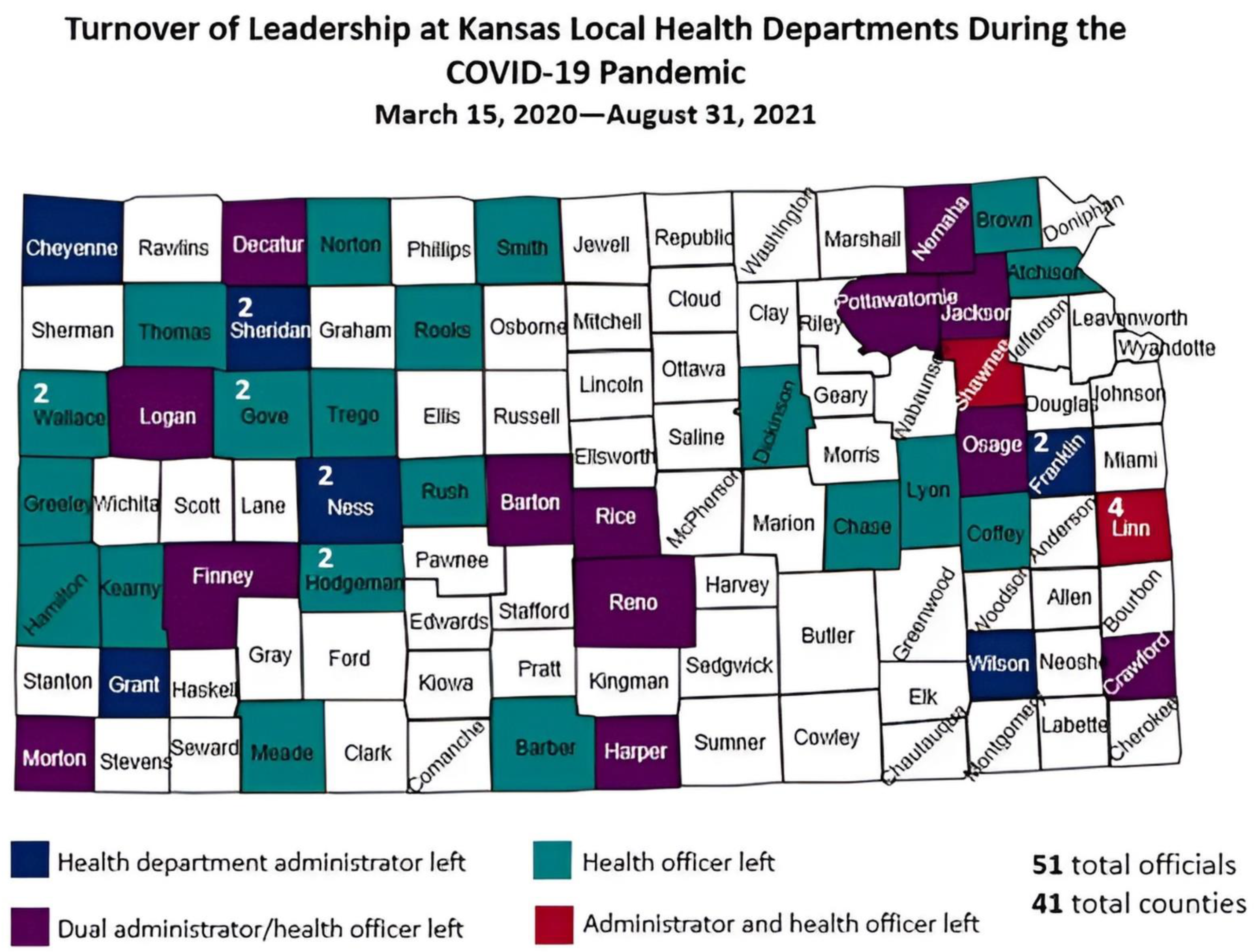

3. Results

3.1. Politicization of Public Health

3.1.1. Extreme Political Divisiveness

Threats

3.2. Lack of Support

3.2.1. Lack of Support from County Commissioners

Lack of Understanding about Public Health

“… when county commissioners become the county board of health, they know nothing about public health, or in a lot of cases, health in general. And on my commission, we had a farmer/rancher, a retired school administrator who substitute teaches, and a banker. No clue. They don’t even know how to read a study.”

“I think it became very apparent and very challenging very quickly when everything became political, and it emboldened politicians to begin to enter into the fray from a political standpoint, not a scientific standpoint. And it’s still continuing to happen today.”

“I can’t tell you how many times I went home crying, or even cried during the middle of the day while I was working. But really, most of that, if not honestly all of that, was feeling like I had absolutely no support, which really, I didn’t. But I just felt like I had none at all.”

3.2.2. Lack of Support from Other County Officials

“My sheriff wasn’t going to help me do quarantine and isolation at all because he felt that was infringing on civil liberties and he wasn’t going to do it. And my county administrator went behind my back and sought legal counsel and told me I was not qualified to be the health officer!”

3.2.3. Lack of Support from the General Public

“…when it feels like the community that you’re trying to protect and serve is turning against you for the very things you’re trying to do for them, it really calls into question everything that you’re doing. And whether it’s worth it or not.”

Public Health Officials under the Social Media Microscope

Unrealistic Expectations, Especially from Sports Parents

“It was tough. I will tell you that we had a lot of people in our community that silently supported us. They stopped in. They apologized for their family members. But they told us… ‘when you guys are getting absolutely lit up on social media, we can’t say anything because this is who we go to Christmas with, or this is who we do business with, or this is who we sell seed to. So we support you. Keep fighting the good fight. We cannot support you publicly.’ So that’s just small town politics.”

Stress and Burnout

“They’re down like 20 people, I think… 15 to 20… and so people are doing two jobs… that’s a tough place to be…. Morale’s low because they’re just exhausted, and it’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Working Extreme Hours

Perceived Pressure to Be Perfect and Accessible

Impact on Family

Public Health Infrastructure Not Working

Poor Communication

Reflecting on Decision to Leave

Recommendations from Participants

“One of the things I’ve learned during the pandemic is that the system doesn’t work. It didn’t work before the pandemic, and it certainly didn’t work during the pandemic. I mean, the fragmentation is absolutely not working. It’s not serving anybody. We’ve got to find a way to protect home ruling while making things more efficient and effective”.

Impact of Turnover

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Public Health in Kansas

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. 2021. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Statista. Death Rates from Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States as of 16 December 2021, by State (Per 100,000 People). 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109011/coronavirus-covid19-death-rates-us-by-state/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Statista. Rate of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cases in the United States as of 16 December 2021, by State (Per 100,000 People). 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109004/coronavirus-covid19-cases-rate-us-americans-by-state/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- White House COVID-19 Team. COVID-19 Community Profile Report. 2020. Available online: https://beta.healthdata.gov/Health/COVID-19-Community-Profile-Report/gqxm-d9w9 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. 2002. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221239/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Robin, N.; Castrucci, B.C.; McGinty, M.D.; Edmiston, A.; Bogaert, K. The first nationally representative benchmark of the local governmental public health workforce: Findings from the 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. J. Public. Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25, S26–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSalvo, K.; Hughes, B.; Bassett, M. Public health COVID-19 impact assessment: Lessons learned and compelling needs. NAM Perspect. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Public Health Governance: State and Local Health Department Governance Classification Map; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Public Health Gateway: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/docs/sitesgovernance/Public-Health-Governance-factsheet.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- County, City-County and Multicounty Units; Local Health Officers; Appointment, Tenure, Removal; Laws Applicable; Review, Amendment or Revocation of Local Health Officer Orders; 65–201. 2021. Available online: http://www.kslegislature.org/li/b2021_22/statute/065_000_0000_chapter/065_002_0000_article/065_002_0001_section/065_002_0001_k/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Local Public Health Program Dataset; Kansas Department of Health and Environment: Topeka, KS, USA, 2021; Unpublished dataset.

- Strochlic, N.; Champine, R.D. How Some Cities ‘Flattened the Curve’ during the 1918 Flu Pandemic; National Geographic: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/how-cities-flattened-curve-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-coronavirus (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Shah, H.B.; Beckman, W.J.; Hunt, D.C.; McClendon, S.; Barstad, P.F.; Sheppard, L.J.; StPeter, R.F. A Kansas Twist: Reopening Plans for Kansas Counties; Kansas Health Institute: Topeka, KS, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.khi.org/articles/a-kansas-twist-2020-reopening-plans-for-kansas-counties/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Howard, J. As Debate around School Mask Mandates Heats up, Local Health Officials Fear for Their Safety; CNN: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/04/health/public-health-officials-safety-threats/index.html (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Policy & Social Research. Population Density Classifications in Kansas by County, 2020; University of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.ipsr.ku.edu/ksdata/ksah/population/popden2.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Newman, S.J.; Ye, J.; Leep, C.J. Workforce turnover at local health departments: Nature, characteristics, and implications. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 5337–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.; Brumfiel, G. Pro-Trump Counties Now Have Far Higher COVID Death Rates. Misinformation is to Blame; National Public Radio: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/12/05/1059828993/data-vaccine-misinformation-trump-counties-covid-death-rate (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Kansas Legislature. About the Kansas Legislature. 2022. Available online: http://www.kslegislature.org/li/about/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Politico. Kansas Presidential Results. 2020. Available online: https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/kansas/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Weber, L.; Barry-Jester, A.M. Over Half of States Have Rolled Back Public Health Powers in Pandemic; Kaiser Health News: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.salon.com/2021/09/17/over-half-of-states-have-rolled-back-public-health-powers-in_partner/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Kansas Association of Local Health Departments. COVID-19 and Threats. 2020. Available online: https://www.kalhd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/COVID-Threats-Summary-10-14-2020.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Bryant-Genevier, J.; Rao, C.Y.; Lopes-Cardozo, B.; Kone, A.; Rose, C.; Thomas, I.; Orquiola, D.; Lynfield, R.; Shah, D.; Freeman, L.; et al. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, K.W.; Kintziger, K.W.; Jagger, M.A.; Horney, J.A. Public health workforce burnout in the COVID-19 response in the U.S. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association of County and City Health Officials. 2015 Local Board of Health National Profile. 2016. Available online: https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Local-Board-of-Health-Profile.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Vaida, B. Fixing the Public Health System for the Next Pandemic; Association of Health Care Journalists: Columbia, MO, USA, 2021; Available online: https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2021/04/fixing-the-public-health-system-for-the-next-pandemic/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Collins, T.; Akselrod, S.; Bloomfield, A.; Gamkrelidze, A.; Jakab, Z.; Placella, E. Rethinking the COVID-19 pandemic: Back to public health. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.; Rosenthal, J. How Investing in Public Health will Strengthen America’s Health; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-investing-in-public-health-will-strengthen-americas-health/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Self-selection bias. In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Kansas Public Health Workforce Assessment; Kansas Department of Health and Environment: Topeka, KS, USA, 2022; Unpublished dataset.

- Gittins, B.G.; Paterson, M.H.; Sharpe, L. How does immediate recall of a stressful event affect psychological response to it? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2015, 46, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 10 | 83% |

| Male | 2 | 17% | |

| Age (in years) | 18 to 29 | 0 | 0% |

| 30 to 39 | 1 | 8% | |

| 40 to 45 | 2 | 17% | |

| 46 to 50 | 4 | 33% | |

| 51 to 55 | 2 | 17% | |

| 56 to 60 | 0 | 0% | |

| 61 to 65 | 1 | 8% | |

| 65 or older | 2 | 17% | |

| Race | Caucasian, White | 12 | 100% |

| African American, Black | 0 | 0% | |

| Asian American, Pacific Islander | 0 | 0% | |

| American Indian, Alaskan Native | 0 | 0% | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic or Latino | 12 | 100% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | 0% | |

| Current region of residence in Kansas | Northeast | 5 | 42% |

| Southeast | 3 | 25% | |

| South Central | 2 | 17% | |

| Northwest | 1 | 8% | |

| Southwest | 1 | 8% | |

| North Central | 0 | 0% | |

| No longer live in Kansas | 0 | 0% | |

| County type | Rural | 6 | 50% |

| Semi-urban | 3 | 25% | |

| Urban | 2 | 17% | |

| Frontier | 1 | 8% | |

| Highest level of education | High school diploma or GED | 0 | 0% |

| Some college credit--no degree | 0 | 0% | |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 0 | 0% | |

| Associate degree | 3 | 25% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 3 | 25% | |

| Master’s degree | 2 | 17% | |

| Professional degree | 0 | 0% | |

| Doctorate degree | 4 | 33% | |

| Registered nurse status | Yes | 7 | 58% |

| No | 5 | 42% | |

| Health department leadership role | Health department administrator | 5 | 42% |

| Dual role as health department administrator and health officer | 5 | 42% | |

| Health officer | 2 | 17% | |

| Reason for departure | Resigned | 9 | 75% |

| Retired | 2 | 18% | |

| Asked to resign | 1 | 8% | |

| Currently employed | Yes | 8 | 67% |

| No | 4 | 33% | |

| Currently in public health, amongst those who were currently employed | Yes | 6 | 75% |

| No | 2 | 25% | |

| Current public health leadership role status | Yes | 4 | 67% |

| No | 2 | 33% | |

| Political affiliation | Republican | 5 | 42% |

| Independent | 3 | 25% | |

| Democrat | 1 | 8% | |

| Something else | 0 | 0% | |

| Preferred not to answer | 3 | 25% |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Politicization of Public Health |

|

Lack of Support from

|

|

| Stress and Burnout |

|

| Public Health Infrastructure Not Working |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cain, C.; Hunt, D.C.; Armstrong, M.; Collie-Akers, V.L.; Ablah, E. Reasons for Turnover of Kansas Public Health Officials during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114321

Cain C, Hunt DC, Armstrong M, Collie-Akers VL, Ablah E. Reasons for Turnover of Kansas Public Health Officials during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114321

Chicago/Turabian StyleCain, Cristi, D. Charles Hunt, Melissa Armstrong, Vicki L. Collie-Akers, and Elizabeth Ablah. 2022. "Reasons for Turnover of Kansas Public Health Officials during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 14321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114321

APA StyleCain, C., Hunt, D. C., Armstrong, M., Collie-Akers, V. L., & Ablah, E. (2022). Reasons for Turnover of Kansas Public Health Officials during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114321