We designed six conversations to demonstrate how the RA would engage a user to accomplish the six main tasks identified in the previous study (Study 1). Since the success of the RA is dependent on the effectiveness (i.e., ability to accomplish the target task) of the conversations, the goal of this study was to improve the effectiveness of the designed conversations through feedback from the healthcare professionals (HCPs).

3.2. Proposed Conversations

The sample conversations used in this study were created in an iterative fashion using a combination of brainstorming amongst the designer and referencing the background research. During the brainstorming sessions, we closely reviewed participants’ comments from Study 1 to conceive dialogues between a patient and the RA. The conversations were refined several times before we landed upon a stable set of conversations that were then evaluated in this study. Our overall goal was to improve these proposed conversations by seeking input from the HCPs.

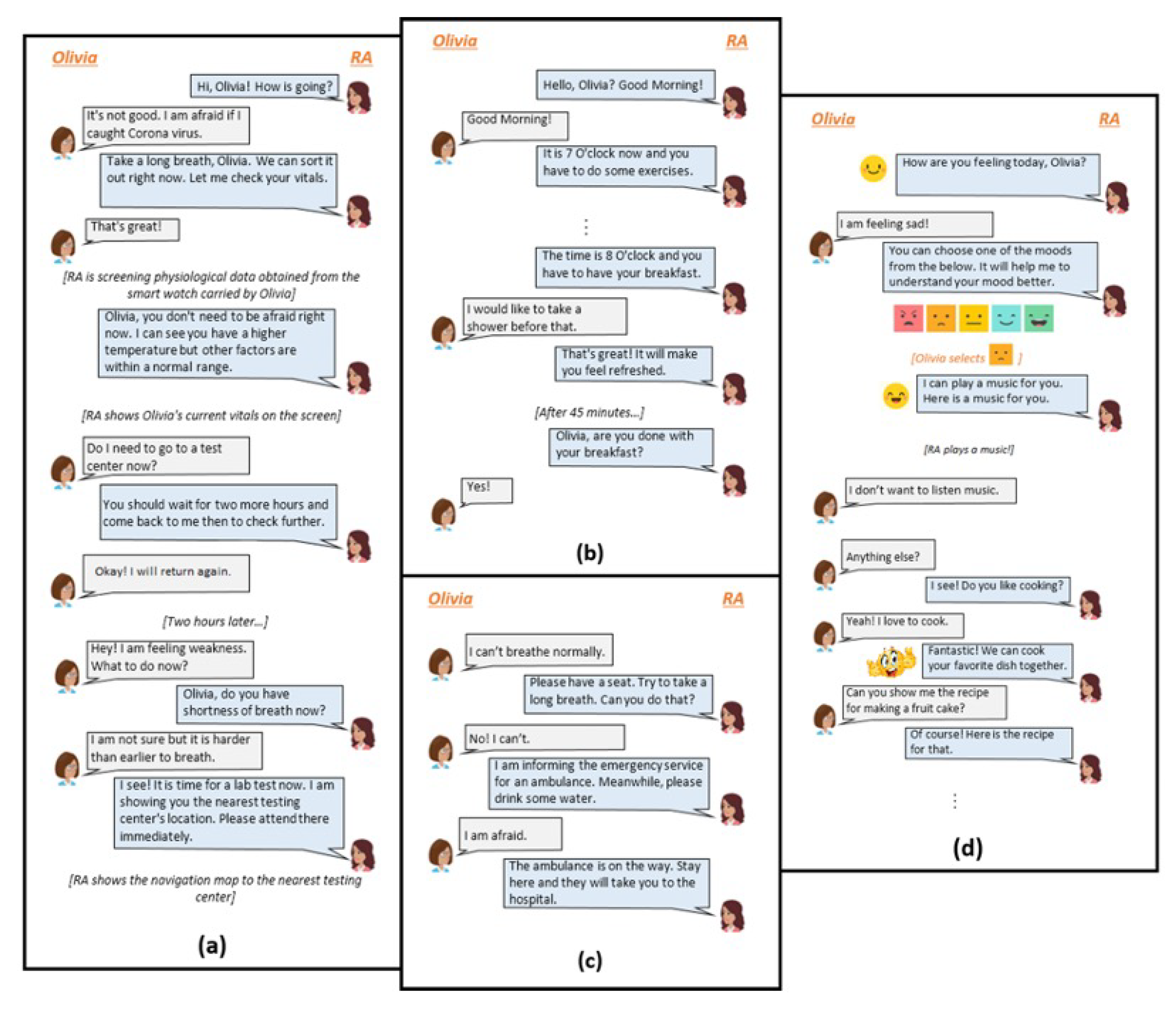

In each conversation, the RA is shown to be conversing with Oli Smith who is representing the target patient persona. Oli is assumed to be an expert user of smartphones and other digital tools such as tablet computers and voice assistants. It is also assumed that Oli has no underlying health conditions. The purpose of each conversation is to help Oli accomplish a certain task or provide a certain health service to Oli in response to an identified need. It is assumed that the RA has an underlying understanding of Oli and it is familiar with their preferences. A few snippets from the conversations have been included in

Figure 1.

Figure 1a illustrates conversations between Oli (Suspecting Infection) and the RA. In this conversation, Oli is not sure whether they have contracted the infection but they are anxious about their existing exasperating condition. They approach the RA to gain some clarify about their symptoms. The RA responds by retrieving their vitals via a smartwatch (Screening for Symptoms) and, based on the analysis of this data makes further recommendations. If the vitals are indicative of COVID-19, the RA provides directions to the nearest COVID-19 testing facility (Providing Testing Guidance). Otherwise, it encourages Oli to practice social distancing and other health promoting habits.

The second conversation (

Figure 1b) demonstrates interactions between Oli and the RA while Oli is in self-isolation at home as a result of being tested positive for COVID-19 (Quarantining at Home). Here, the RA is encouraging Oli to practice healthy habits to speed up recovery and prevent further health declines (Encouraging Healthy Behaviors). The conversation snippet in

Figure 1c demonstrates how the RA handles an emergency, i.e., Oli reporting a severe breathing problem to the RA (Handling Emergency Situations).

Figure 1d shows how the RA will help Oli, who has just recovered from the infection (Recovering after Infection), regulate her mental health issue (Promoting Mental Well-being), regain confidence, and recover from the trauma they had experienced during their hospital stay. Here the RA is assumed to be familiar with the source of Oli’s trauma.

3.3. Participants

The following criteria were used to determine the eligibility for participation: (a) age of at least 18 years, (b) working in a healthcare setting, (c) familiarity with COVID-19-related guidelines and health concerns, (d) ability to speak, write and understand English, and (e) familiarity with mHealth technology. Forty-three HCPs (female = 29) ended up completing the survey in its entirety. In terms of occupation, 18 HCPs were providers (primary care, specialist, etc.), 21 were health care workers (registered nurse, nurse assistant, physician assistant, therapist, paramedic, etc.), 2 were medical students, and the remaining 2 were clinical social workers. Participants were of various ages ranging from 20 years to 60 years, with mean age 30.94 years (SD = 11.01). In terms of COVID-19 infection and symptoms, 28 had never been infected, 7 had recovered from the mild infection, 4 had recovered from severe infection, and the rest were asymptomatic. 19 HCPs had experience caring for a COVID-19 patient and everyone was staying abreast with the recent developments in COVID-19 by the virtue of reading research articles, newspapers, following changes in work protocols, and working in the COVID-19 intensive care unit, etc.

3.5. Results

Irrespective of their prior experience in caring for the COVID-19 patients, HCPs were proficient in terms of making suggestions for improving the proposed conversations. All nineteen HCPs who had cared for the COVID-19 patients believed that the proposed conversations with improvements would be sufficient for helping the patients with the three disease stages explored in this study.

The thematic analysis resulted in fifty-seven codes related to improving the proposed conversations (

Table 3). These codes were clustered into four major themes and twelve categories. A substantial (22) number of codes were about improving the system’s robustness, i.e., redesigning it to more accurately mimic the clinical protocols and patient-provider interactions. For example, HCPs wanted to improve system’s robustness by having it model clinical interactions, providing care based on patient-centered principles, and incorporating evidence-based mental health interventions. The HCPs thought that the users would be more willing to trust an RA that is able to meet users’ realistic expectations and facilitate connections with actual HCPs. They believed that socio-emotional support must be shown by the RA through demonstration of empathy, validation of users’ emotions, and incorporating peer support. The study participants also recommended that the RA should be able to engage patients in their care by conducting periodic mood and health assessments. They also thought that education and reminders can also increase patient’s engagement with self-care. In addition, HCPs believed that age, income, and language differences would have an impact on the RA’s widespread acceptance. Hence, they recommended that the proposed system should be validated with a diverse population.

3.5.1. Model Clinical Protocols

Three participants recommended improving the RA’s screening mechanism and accuracy by incorporating additional questions and a triage process. Triage is a medical practice that is used for the prioritization of care when there is a lack of resources [

51]. It first determines the severity of a condition and then recommends appropriate actions based on identified needs. The participants recommended that the RA should start the screening process by asking questions about the presence and severity of symptoms. This would help identify those patients for whom COVID-19 testing or medical care (e.g., shortness of breath, fever) is urgently needed. Next, patients who have had direct contact with other COVID-19 positive individuals should be identified. These patients may not report concerning symptoms but require laboratory tests. Finally, patients who report no concerning symptoms or contact should have their vital signs evaluated.

“... A lot of questions could have been asked initially before giving the reassurance that everything was okay because most of her vitals were okay. The high temperature should have been enough of a reason to test. Also, should have asked if she had been exposed to someone who was positive, if she has lost taste/smell, what symptoms she was having, etc.” (HCP-14, Screening for Symptoms).

This theme shows that HCPs recognize that an RA can screen patients for the COVID-19 infection. However, the screener must be accurate, comprehensive, and robust, and based on established medical practices. Additional devices such as an oximeter, a thermometer, a heart rate monitor, etc., may be required to achieve this goal. Hence, such devices must be easily accessible to patients, and/or patients have the capability to interface such devices with the RA.

3.5.2. Provide Person-Centered Care

Even though the conversations demonstrated that the RA had been designed to provide person-centered care to the user, participants recommended that the personalization feature of the system should be further refined. They explained that patients’ personal preferences and interests change based on the severity of their condition. They recommended that the health information and self-management strategies recommended by the RA must be aligned with disease symptoms instead of only with patients’ preferences. The HCPs explained that the symptoms of depression and anxiety aggravate with the progression of the COVID-19, which directly impacts patients’ engagement with the tasks and activities they had once enjoyed.

“If someone is truly depressed or suffering from a mental disorder, they likely won’t have the motivation to do a complicated task like cooking, even if they enjoyed doing it before.” (HCP-12, Supporting Mental Well-being)

The codes belonging to this theme appeared with the highest frequency, indicating that taking a person-centered approach needs to be at the forefront of RA-based care. This theme also indicates that the RA needs to stay updated with patients’ current health status and update its recommendation algorithm accordingly.

3.5.3. Integrate Diverse and Evidence-Based Mental Health Interventions

Participants appreciated that the system was sensitive to patients’ mental health needs, and it tried to address them by suggesting coping strategies inspired by patients’ values at every stage of COVID-19 disease. However, they stressed the importance of incorporating evidence-based mental health interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy, positive psychology, etc.

“... have evidence-based interventions in place for mental health or behavioral issues for people who are having mild cases. The anxiety of isolation as well as the anxiety of not knowing how severe the disease process is going to be is intense. Fatigue can also cause intense depression. It’s important for these symptoms to be normalized with tried and tested methods.” (HCP-6, Supporting Mental Wellbeing).

Participants also recommended that the RA should include evidence-based educational content that help help patients cope with anxiety, depression, and other common mental health issues that are likely to manifest due to the infection.

“I’ve cared for many patients who are suffering from COVID at home alone, and something that they all crave is mental health support. This is essential, especially for the elderly and those living at home on their own. Perhaps the bot may suggest an anxiety scale 1-5 and depression scale 1-5 and suggest telehealth psychologists or social workers for support.” (HCP-11, Encouraging Healthy Behaviors).

Mental health interventions are very important for COVID-19 patients. There are multiple ways to incorporate and deliver these interventions using an RA. HCPs recommend flexibility (offering multiple modes) and compatibility (matching user’s needs) when delivering these interventions. Since COVID-19 patients encounter mental health issues at every disease stage, it is important to incorporate a diverse array of interventions to ensure patients’ long-term engagement with the RA.

3.5.4. Validate Patient’s Feelings

Participants also emphasized the importance of validating patients’ fears and concerns whenever they expressed their anxieties to the RA or whenever the RA detected changes in the patients’ mental health status through surveys.

“Telling someone not to be afraid when they are afraid is useless. Validate them and perhaps guide them through techniques to lower anxiety.” (HCP-5, Handling Emergency Situations).

“The RA should acknowledge that this is a tough illness and more will be coming down the pike. And, it should encourage the patients to learn to manage themselves over time.” (HCP-35, Handling Emergency Situations).

There are specific and sensitive approaches to communicating with those who are recovering from a challenging disease such as COVID-19. HCPs advised that specific approaches must be adopted in conversations to support the building of patients’ trust in the system.

3.5.5. Set Realistic Expectations

Participants pointed out that the RA should not make a promote that it cannot deliver on. They believed that an important principle of building user’s trust in the RA should be about making sure that the user is not disappointed with the services offered by the system.

“Do not promise people they will be okay. Offer reassurance but don’t lie. Better to say, ‘you will get the best care possible’.” (HCP-10, Handling Emergency Situations).

Participants advocated for the RA to be autonomous in recognizing critical conditions and seeking emergency assistance, i.e., circumstances in which the patient may be unable to communicate and ask for help. They believed that RA’s ability to act autonomously is a realistic expectation, which users should be able to bank on in times of need.

“In some cases, patients can not respond and the guide should act independently to contact emergency services.” (HCP-12, Handling Emergency Situations).

The HCPs’ comments suggest that a clear understanding of the system’s capabilities has the potential to increase users’ trust in the system and make it more appealing to use. Moreover, the system must make its capabilities and services as transparent to the patient as possible.

3.5.6. Facilitate Professional Connections

Participants suggested that besides designing the RA to provide mental health service, the RA should also allow patients to schedule remote consultation with human psychologists. Specifically, participants thought that this would be valuable for patients recovering from the infection and for those facing emergencies at home. They also recommended that the system should allow patients to connect with their primary or urgent care providers, in case they require consultation.

“Connect to a physician too if patient too afraid.” (HCP-7, Handling Emergency Situations)

HCPs believe that patients would feel more comfortable using a system that puts them in the vicinity of HCPs. In addition, such a system is likely to improve patient’s belief that the system can help them in emergencies. However, this suggestion conflicts with the original aim of the system, which is to minimize patients’ reliance on traditional healthcare facilities. If professional support is to be incorporated into the system, then it must be offered as the last resort after the users have exhausted all the resources offered by the system itself.

3.5.7. Incorporate Peer Support

Participants unanimously agreed that the RA should allow patients to communicate with their loved ones. They believed that connection with their peers could be a very valuable for addressing patients’ mental health needs during the quarantine and the recovery periods.

“The requirement of physical and social distancing means we are no longer social beings. This has led to a lot of issues with isolation. When we are sick, we want to alleviate the burden of disease on our loved ones. The patients should be engaging their contacts 1-2 times a day to report their symptoms are okay.” (HCP-38, Encouraging Healthy Habits).

“Communication with loved ones may help in reducing PTSD. Inclusion of this feature is highly appreciated.” (HCP-9, Supporting Mental Well-being).

Moreover, participants thought that giving patients the ability to share their disease and recovery experiences with other COVID-19 positive patients would be an important step in improving patients’ mental health when they are scared.

“Communication should be encouraged among people who had COVID-19 to share their experiences.” (HCP-12, Encouraging Healthy Behaviors and Supporting Mental Well-being).

The HCPs believe that peer and family support is essential for improving the mental well-being of patients. HCPs encouraged that the patients not only share their previous experiences (related to COVID-19) with each other but also build new experiences together (e.g., by doing a psychological intervention session together). The RA should be able to create social network support and encourage the adoption of health-promoting behaviors in patient groups.

3.5.8. Conduct Periodic Assessments

There was a consensus among the participants that the RA should be able to conduct periodic assessments of patients’ mental and physical health. This was considered necessary at all stages of COVID-19. HCP-2 recommended that the RA should periodically screen the patients for COVID-19 symptoms during the pre-diagnosis stage, regardless of whether the previous screening attempt resulted in a recommendation for testing or not. In both cases, the RA should ensure that the patient has received appropriate care and is not in any danger.

“Ask about more frequently symptoms, check in within 1 h vs. 2 h when patients are suspecting infection.” (HCP-2, Screening for Symptoms).

Participants suggested that during quarantine and post-infection periods, the RA should frequently be asking the patient about their health status, asking them to focus on their symptoms, monitoring their vital signs, and surveying them about the severity and presence of symptoms. The goal of these frequent check-ins is to figure out the care required by the patient and to provide them socio-emotional support. Another goal is to ensure that the patients receive care before their illness becomes too severe.

HCPs’ proposals clarify that periodic assessments by the RA would be beneficial for patients through all stages of the COVID-19 disease. Both passive (with the help of connected medical devices such as a pulse oximeter, a blood pressure, and a heart rate monitor) and active check-ins methods (i.e., surveys) were supported by the HCPs with the belief that having this would increase patient’s engagement with the system. However, it is also possible that constantly requiring feedback will increase patient fatigue and burden, causing them to abandon the use of the system altogether. Therefore, it is important to understand and adjust the frequency of these check-ins according to user’s response.

3.5.9. Inform, Motivate, Remind

Participants suggested that the RA should provide accurate and up-to-date information about the pandemic. They recommended that the RA should deliver various kinds of educational content to the user. For example, they recommended that the RA should educate the user about how to manage the disease, such as learning to identify the alarming symptoms, how to do breathing/lung exercises to prevent exasperating conditions, encouraging patients to eat healthily and stay hydrated, and encouraging them to perform physical activities.

“Even if patients have normal vital signs and guidance is subsequently given for testing, it would conclude with an educational message with warning/alarm symptoms to look out for. If they feel bad, then do a critical assessment of not only your symptoms but also vital signs.” (HCP-6, Screening for Symptoms and Providing Testing Guidance).

“Patients should be taught the risk of not taking preventative measures. If they are not coughing, not moving, not taking deep breaths, then they are at risk of secondary infection.” (HCP-28, Encouraging Healthy Habits).

“Every hour, on the hour, remind them to get up and walk through the house for no good reason other than just to move. Motivating them is important.” (HCP-32, Encouraging Healthy Habits).

Participants indicated that the presentation of the educational content is important as it can have an influence on a patient’s ability to comprehend it and implement it in their lives. They thought that multimedia content would appeal to a wider audience.

“Including diagrams and images of COVID-19 test procedures and adding some helpline number.” (HCP-3, Screening for Symptoms and Providing Testing Guidance).

Health education and informational social support are important in the self- management of any disease. This theme suggests that HCPs believed that the RA has the potential to educate patients. It is important to understand how information is being presented to the users, since this can have a huge impact on a patient’s ability to understand and implement what is being presented to them.

3.5.10. Accommodate Diverse Patients

The HCPs suggested that three factors (i.e., age, income, and language) should be considered in the design of the RA. Older adults, for example, usually have specific needs and limitations, which have an impact on their abilities to interact with the digital technology. For example, they might have hearing and visual impairment that can impact their ability to effectively use the RA.

The HCPs also stressed the importance of accommodating low-income patients because they felt that some features of the RA may pose a burden on them. For example, in the original conversations, the RA offers to order breakfast from a nearby café. The HCP pointed out that this might pose a burden on the patients. Moreover, income level also has an implication on what input and output devices the RA should be interfacing with, since low-income users may not be able to afford expensive external devices. However, acquiring income information from the user may be awkward and indirect methods could be used to obtain this data from the user.

Moving forward, it will be important to assess the feasibility of the proposed RA with different patient populations.