The Increasing Population Movements in the 21st Century: A Call for the E-Register of Health-Related Data Integrating Health Care Systems in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Crisis of Population Displacement in Europe

1.2. Transiting Borders by Vulnerable Individuals Who Require Health Assistance and Complex Care

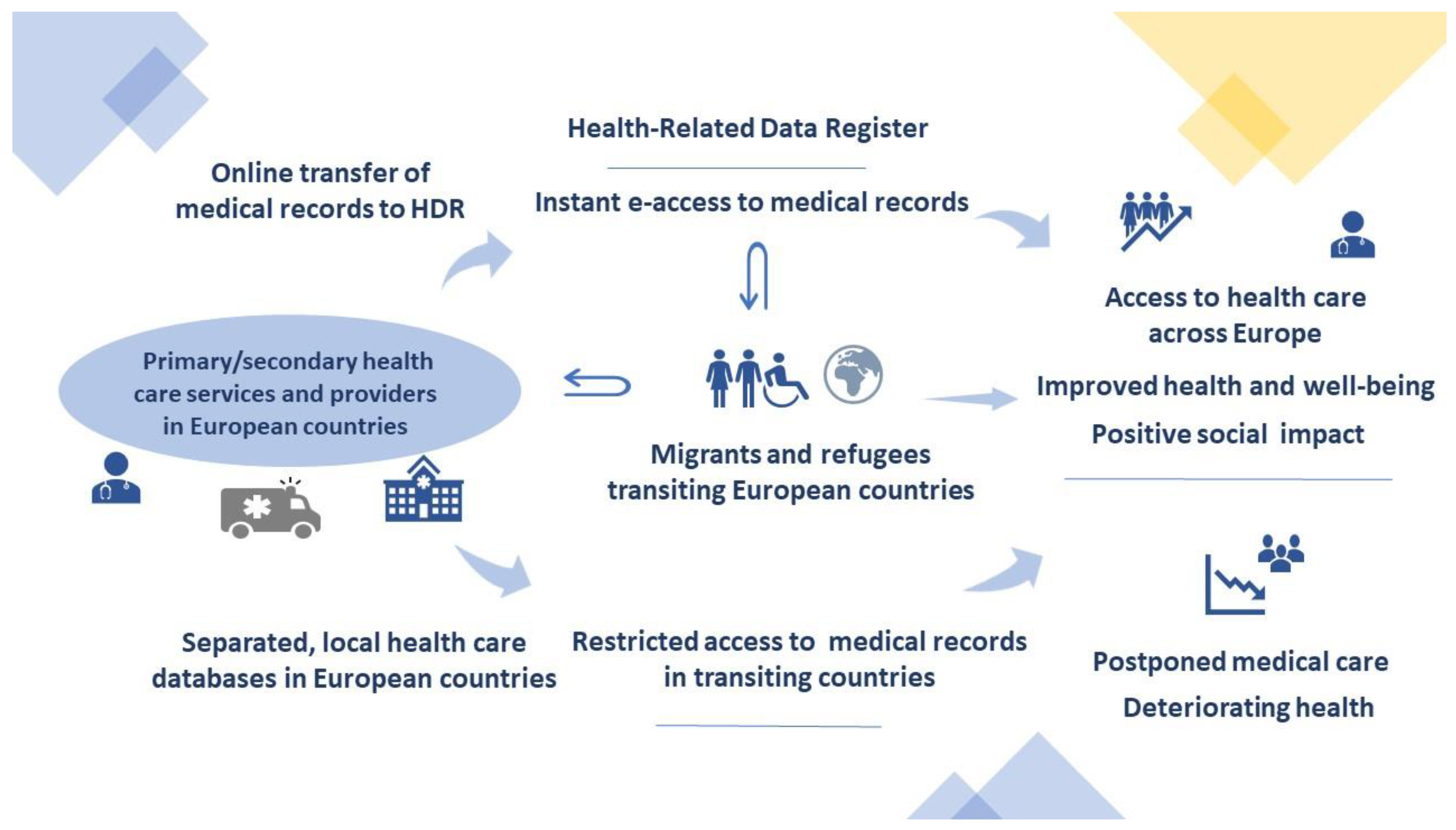

2. A Central Electronic Register Integrating Health-Related Data in Europe

Potential Constraints and Implications of Broad Online Data Sharing

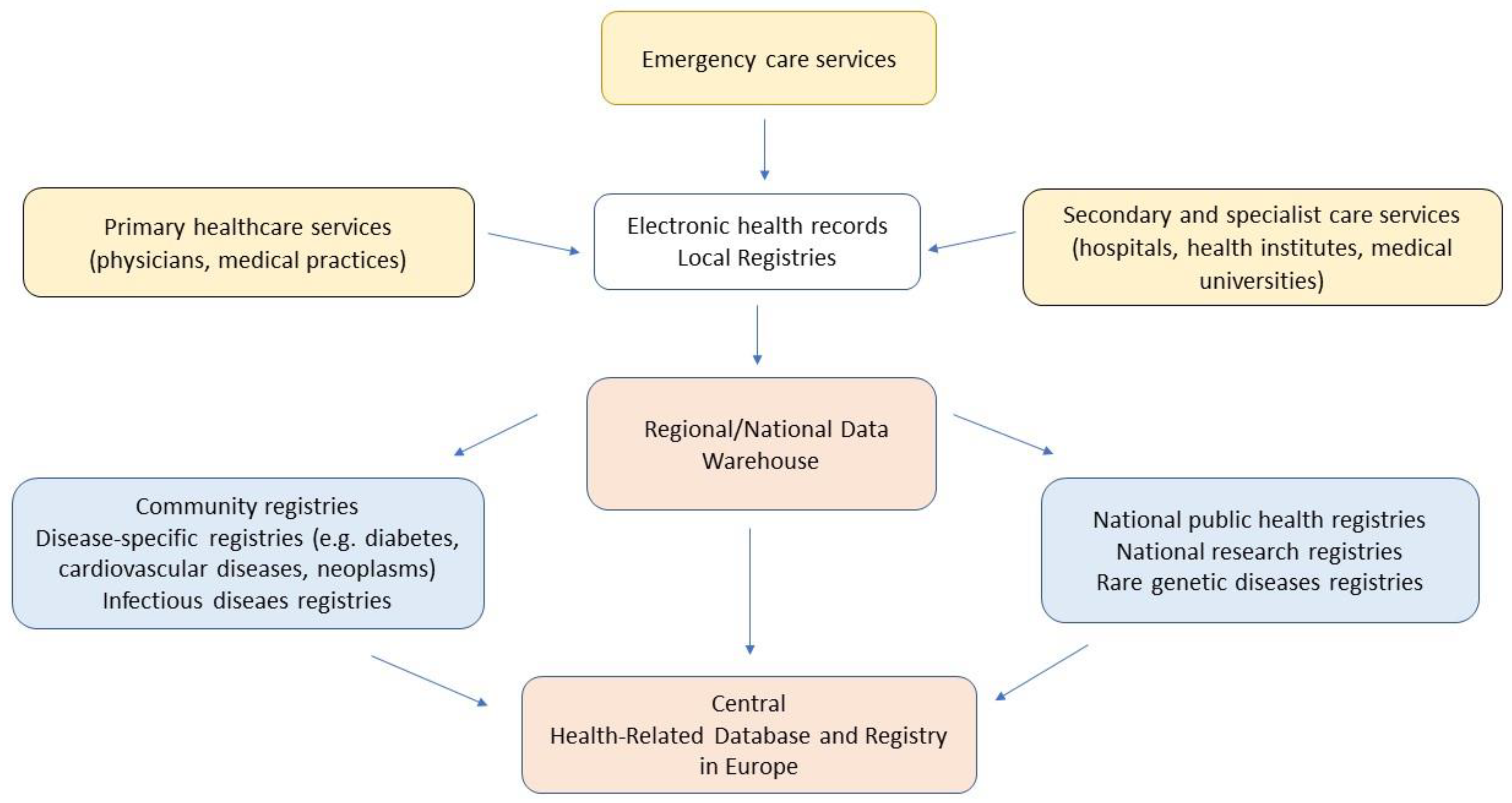

3. Proposed Action to Initiate a Central European E-Health Database Rollout

- Wide-scale upgrade of currently functioning health registries and e-systems in European countries on local, regional, and national levels.

- Identification of crucial, compatible IT infrastructures to allow a unification of data exchange.

- EU legislation approving a centralized health-related data storage system, with an open collaboration of all European countries, also not formally members of European Union.

- Allocation of individual health care numbers allowing the access to public health care for persons with formal migrant/refugee status.

- Implementation of individual e-health account and/or mobile appt, including copies of medical records (translation options).

- Integration of local health care providers’ databases linked to the EU; legally approved and commissioned central online storage database of healthcare records. Data can be imported and exported between EU countries.

- Optimization and standardization of e-data exchange between countries based on advanced IT infrastructure.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamenshchikova, A.; Margineau, I.; Munir, S.; Knights, F.; Carter, J.; Requena-Mendez, A.; Ciftci, Y.; James, R.A.; Orcutt, M.; Blanchet, K.; et al. Health-care provision for displaced populations arriving from Ukraine. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Fuhr, D.; Roberts, B.; Jarvis, C.I.; Tarasenko, A.; McKee, M. The health needs of refugees from Ukraine. BMJ 2022, 377, o864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewtak, K.; Kanecki, K.; Tyszko, P.; Goryński, P.; Bogdan, M.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Ukraine war refugees—Threats and new challenges for healthcare in Poland. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 125, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Operational Data Portal. Ukraine Refugees Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/Ukraine (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- European Migration Network. Annual Report on Migration and Asylum in 2021. June 2022. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/european-migration-network-emn/emn-publications/emn-annual-reports_en (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Chiesa, V.; Chiarenza, A.; Mosca, D.; Rechel, B. Health records for migrants and refugees: A systematic review. Health Policy 2019, 123, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, M.; Gujski, M. Editorial: The Public Health Implications for the Refugee Population, Particularly in Poland, Due to the War in Ukraine. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e936808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; McDonnell, D.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Ahmad, J.; Šegalo, S.; Pereira da Veiga, C.; Xiang, Y.T. Public health crises and Ukrainian refugees. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 103, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platform on International Communication on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM). Available online: www.picum.org/publications (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Holt, E. Growing concern over Ukrainian refugee health. Lancet 2022, 399, 1213–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odone, A.; Buttigieg, S.; Ricciardi, W.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Staines, A. Public health digitalization in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29 (Suppl. 3), 28–35, Erratum in Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaxe, E.; Czypionka, T.; Kraus, M.; Reiss, M.; Askildsen, J.E.; Grenkovic, R.; Lindén, T.S.; Pitter, J.G.; Rutten-van Molken, M.; Solans, O.; et al. Digital Health Transformation of Integrated Care in Europe: Overarching Analysis of 17 Integrated Care Programs. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.N.; James, R.; Hargreaves, S.; Bozorgmehr, K.; Mosca, D.; Hosseinalipour, S.M.; AlDeen, K.N.; Tatsi, C.; Mussa, R.; Veizis, A.; et al. Meeting the health needs of displaced people fleeing Ukraine: Drawing on existing technical guidance and evidence. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 17, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Loboda, A. Systematic review of health and disease in Ukrainian children highlights poor child health and challenges for those treating refugees. Acta Paediatr. 2022, 111, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenop, J.; Brake, T.; Mauder, S.; Razum, O. Gesundheitliche Lage in der Ukraine vor Kriegsbeginn und ihre Relevanz für die Versorgung ukrainischer Geflüchteter in Deutschland: Literaturdurchsicht, Risikoanalyse und Prioritätensetzung [Health Situation in Ukraine Before Onset of War and Its Relevance for Health Care for Ukrainian Refugees in Germany: Literature Review, Risk Analysis, and Priority Setting]. Gesundheitswesen 2022, 84, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mapping Health Systems’ Responsiveness to Refugee and Migrant Health Needs. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030640 (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- World Health Organisation. WHO Report Shows Poorer Health Outcomes for Many Vulnerable Refugees and Migrants. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-07-2022-who-report-shows-poorer-health-outcomes-for-many-vulnerable-refugees-and-migrants (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Zenner, D.; Méndez, A.R.; Schillinger, S.; Val, E.; Wickramage, K. Health and illness in migrants and refugees arriving in Europe: Analysis of the electronic personal health record system. J. Travel Med. 2022, 2, taac035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenstein, V.; Kharrazi, H.; Lehmann, H.; Taylor, C.O. Obtaining Data from Electronic Health Records. In Tools and Technologies for Registry Interoperability, Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide, 3rd ed.; Gliklich, R.E., Leavy, M.B., Dreyer, N.A., Eds.; Chapter 4; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551878/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), Department of Health and Human Services. Health information technology: Standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology, 2014 edition; revisions to the permanent certification program for health information technology. Final rule. Fed. Regist. 2012, 77, 54163–54292. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.S.; Fowles, J.B.; Weiner, J.P. Review: Electronic health records and the reliability and validity of quality measures: A review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2010, 67, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, E.V.; Haines, A.; Tomson, G.; Ghaffar, A. Refugees: Towards better access to health-care services. Lancet 2016, 387, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Makes It Easier for Citizens to Access Health Data Securely across Borders. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_842 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- European Commission. Digital Health Europe. Citizens’ Secure Access to and Sharing of Health Data across Borders. Available online: https://digitalhealtheurope.eu/multi-stakeholder-communities/citizens-access/ (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- United Nations Sustainable Development. Department of Social and Economic Affairs. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- European Commission. Electronic Cross Border Health Services. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/electronic-cross-border-health-services_en (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Xiang, D.; Cai, W. Privacy Protection and Secondary Use of Health Data: Strategies and Methods. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6967166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, D.; Mandl, K.D. Privacy protections to encourage use of health-relevant digital data in a learning health system. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.B.; Jensen, L.J.; Brunak, S. Mining electronic health records: Towards better research applications and clinical care. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostick-Quenet, K.; Mandl, K.D.; Minssen, T.; Cohen, I.G.; Gasser, U.; Kohane, I.; McGuire, A.L. How NFTs could transform health information exchange. Science 2022, 375, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Lin, X. Towards Secure and Privacy-Preserving Data Sharing in e-Health Systems via Consortium Blockchain. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernian, A.; Tiganoaia, B.; Sacala, I.; Pavel, A.; Iftemi, A. PatientDataChain: A Blockchain-Based Approach to Integrate Personal Health Records. Sensors 2020, 20, 6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dziedzic, A.; Riad, A.; Tanasiewicz, M.; Attia, S. The Increasing Population Movements in the 21st Century: A Call for the E-Register of Health-Related Data Integrating Health Care Systems in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113720

Dziedzic A, Riad A, Tanasiewicz M, Attia S. The Increasing Population Movements in the 21st Century: A Call for the E-Register of Health-Related Data Integrating Health Care Systems in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113720

Chicago/Turabian StyleDziedzic, Arkadiusz, Abanoub Riad, Marta Tanasiewicz, and Sameh Attia. 2022. "The Increasing Population Movements in the 21st Century: A Call for the E-Register of Health-Related Data Integrating Health Care Systems in Europe" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113720

APA StyleDziedzic, A., Riad, A., Tanasiewicz, M., & Attia, S. (2022). The Increasing Population Movements in the 21st Century: A Call for the E-Register of Health-Related Data Integrating Health Care Systems in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113720