Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

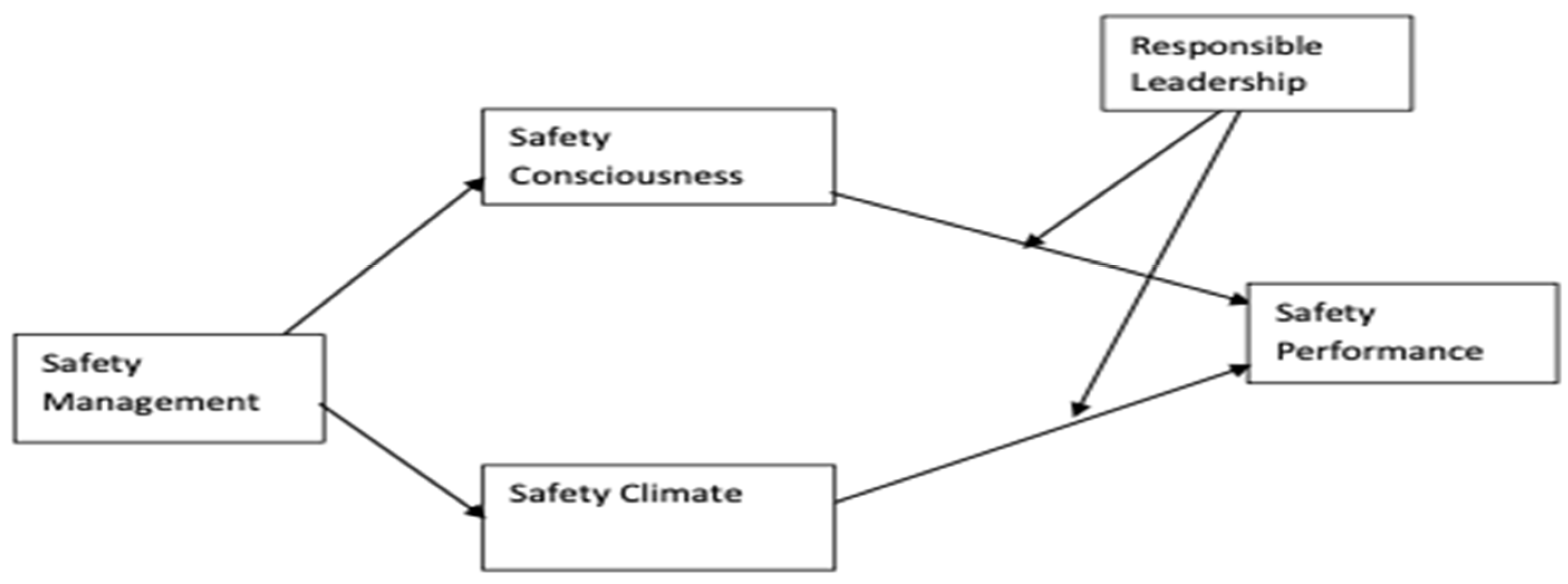

Theoretical Framework

2. Literature Review

2.1. Safety Management and Safety Consciousness

2.2. Safety Management and Safety Climate

2.3. Safety Climate and Safety Performance

2.4. Safety Consciousness and Safety Performance

2.5. Responsible Leadership as Moderator for Safety Consciousness and Safety Performance

2.6. Responsible Leadership as Moderator for Safety Climate and Safety Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Instrumentation

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Common Method Variance

4.3. Scale Validation

4.4. Statistical Assumptions

4.4.1. Normality Analysis

4.4.2. Reliability Analysis

4.4.3. Validity Analysis

4.5. Hypotheses Testing

4.6. Mediation Model

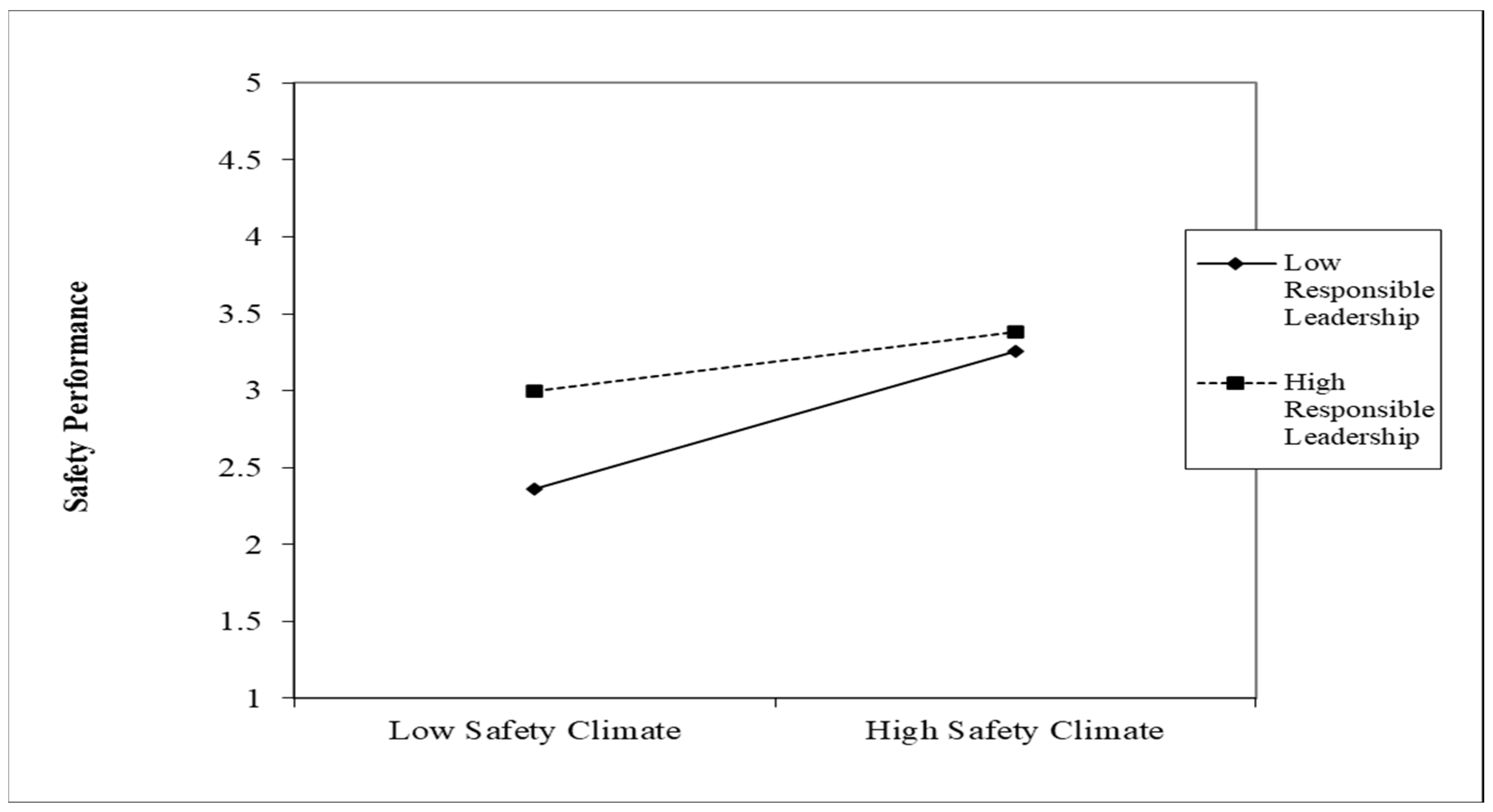

4.7. Moderation Analysis

4.8. Mediated Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications

8. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire

- I always take extra time to do things safely.

- People think of me as being an extremely safety-minded person.

- I always avoid dangerous situations.

- I take a lot of extra time to do something safely even if it slows my performance.

- I often find myself making sure that other people do things that are safe and healthy.

- I get upset when I see other people acting dangerously.

- Doing the safest possible thing is always the best thing.

- I always comply with the safety standards and procedures.

- I am convinced about the importance of the safety procedures.

- I use the personal protection equipment even if it is uncomfortable.

- I participate in setting objectives and drawing up plans to improve safety.

- I participate in evaluating risk.

- I participate in the safety inspections.

- I make suggestions about how to improve the working conditions.

- I frequently discuss safety problems with their superiors.

- Periodic checks conducted on execution of prevention plans and compliance level of regulations.

- Standards or pre-determined plans and actions are compared, evaluating implementation and efficacy in order to identify corrective action.

- Procedures in place (reports, periodic statistics) to check achievement of objectives allocated to managers.

- Systematic inspections conducted periodically to ensure effective functioning of whole system.

- Accidents and incidents reported, investigated, analyzed, and recorded.

- Firm’s accident rates regularly compared with those of other organizations from same sector using similar production processes.

- Firm’s techniques and management practices regularly compared with those of other organizations from all sectors, to obtain new ideas about management of similar problems.

- Safety policy:

- (1)

- Firm coordinates its health and safety policies with other HR policies to ensure commitment and well-being of workers.

- (2)

- Written declaration is available to all workers reflecting management’s concern for safety, principles of action and objectives to achieve.

- (3)

- Safety policy contains commitment to continuous improvement, attempting to improve objectives already achieved.

- Training in safety:

- (1)

- Worker given sufficient training period when entering firm, changing jobs or using new technique.

- (2)

- Training actions continuous and periodic, integrated in formally established training plan.

- (3)

- Training plan decided jointly with workers or their representatives.

- (4)

- Firm helps workers to train in-house (leave, grants).

- (5)

- Instruction manuals or work procedures elaborated to aid in preventive action.

- Communication in prevention issues:

- (1)

- There is a fluent communication embodied in periodic and frequent meetings, campaigns or oral presentations to transmit principles and rules of action.

- (2)

- Information systems made available to affected workers prior to modifications and changes in production processes, job positions or expected investments.

- (3)

- Written circulars elaborated on and meetings organized to inform workers about risks associated with their work and how to prevent accidents.

- Preventive planning:

- (1)

- Prevention plans formulated setting measures to take on basis of information provided by risks assessment in all job positions.

- (2)

- Standards of action or work procedures elaborated on basis of risk evaluation.

- (3)

- Prevention plans circulated among all workers.

- (4)

- Firm has elaborated emergency plan for serious risks or catastrophes.

- (5)

- Firm has implemented its emergency plan.

- (6)

- All workers informed about emergency plan.

- (7)

- Periodic simulations carried out to check efficacy of emergency plan.

- My direct supervisor demonstrates awareness of the relevant stakeholder claims.

- My direct supervisor considers the consequences of decisions for the affected stakeholders.

- My direct supervisor involves the affected stakeholders in the decision-making process.

- My direct supervisor weighs different stakeholder claims before making a decision.

- My direct supervisor tries to achieve a consensus among the affected stakeholders.

References

- Daito, A.; Riyanto, S.; Nusraningrum, D. Human Resource Management Strategy and Safety Culture as Competitive Advantages in Order to Improve Construction Company Performance. Bus. Entrep. Rev. 2020, 20, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, S.; Nugraha, A.; Sulistiyono, B.; Suryaningsih, L.; Widodo, S.; Kholdun, A.; Endri, E. The effect of safety risk management and airport personnel competency on aviation safety performance. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hua, X.; Huang, G.; Shi, X. How Does Leadership in Safety Management Affect Employees’ Safety Performance? A Case Study from Mining Enterprises in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Goh, Y.M.; Jensen, O.; Asmore, A.S. The impact of climate change on workplace safety and health hazard in facilities management: An in-depth review. Saf. Sci. 2022, 151, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.D.; Frost, D. Health at Work—An Independent Review of Sickness Absence; TSO: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Intini, P.; Berloco, N.; Coropulis, S.; Gentile, R.; Ranieri, V. The use of macro-level safety performance functions for province-wide road safety management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, B. Safety management assessment and task analysis—A missing link? In Safety Management: The Challenge of Change; Hale, A., Baram, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Westaby, J.D.; Lee, B.C. Antecedents of injury among youth in agricultural settings: A longitudinal examination of safety consciousness, dangerous risk taking, and safety knowledge. J. Saf. Res. 2003, 34, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheyne, A.; Cox, S.; Oliver, A.; Tomás, J.M. Modelling safety climate in the prediction of levels of safety activity. Work Stress 1998, 12, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Loughlin, C.; Kelloway, E.K. Development and test of a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koster, R.B.; Stam, D.; Balk, B.M. Accidents happen: The influence of safety-specific transformational leadership, safety consciousness, and hazard reducing systems on warehouse accidents. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeepers, N.C.; Charles, M. A study on the leadership behaviour, safety leadership and safety performance in the construction industry in South Africa. Proc. Manuf. 2015, 4, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, B.Z.; Schmidt, W.H. An updated look at the values and expectations of federal government executives. Public Adm. Rev. 1994, 54, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Nabeel, S. Tunneling: Evidence from family business groups of Pakistan. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, S.; Mahmood, W. Corporate governance and value of family-owned business: A case of emerging country. Corp. Gov. Sustain. Rev. 2018, 2, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of SMEs in Pakistan. Daily Pakistan. 29 May 2021. Available online: https://dailytimes.com.pk/763512/state-of-smes-in-pakistan/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Khan, M. Scenario of manufacturing pharmaceutical small and medium enterprises (smes) in Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Stud. 2015, 1, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.C. Social systems theory and practice: The need for a critical approach. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 1985, 10, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzels, J.W.; Egon, G.G. Social behavior and the administrative process. Sch. Rev. 1957, 65, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornstein, A.C.; Hunkins, F.P. Curriculum: Foundatıons. Principles and Issues, 2nd ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Skyttner, L. General Systems Theory: Problems, Perspectives, Practice; World Scientific: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Riehle, A.; Braun, B.I.; Hafiz, H. Improving patient and worker safety: Exploring opportunities for synergy. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2013, 28, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Törner, M. The “social-physiology” of safety. An integrative approach to understanding organisational psychological mechanisms behind safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeh, P. Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.S. Responsible leadership. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cieri, H.; Shea, T.; Pettit, T.; Clarke, M. Measuring the Leading Indicators of Occupational Health and Safety: A Snapshot Review. Institute of Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research. 2012, pp. 5–30. Available online: https://workplacehealthsafetyresearch.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/measuring-the-leading-indicators-of-ohs-snapshot-review-2012.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Waldman, D.A.; Balven, R.M. Responsible leadership: Theoretical issues and research directions. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, O.; McColl, J.; Pfefferkorn, T.; Hamadneh, S.; Alshurideh, M.; Kurdi, B. Consumer attitudes towards the use of autonomous vehicles: Evidence from United Kingdom taxi services. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ahmad, I.; Ilyas, M. Impact of ethical leadership on organizational safety performance: The mediating role of safety culture and safety consciousness. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 628–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Fu, S.; Weng, J. Analysis of safety climate effect on individual safety consciousness creation and safety behaviour improvement in shipping operations. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Isha, A.S.N.; Nordin, S.M.; Al-Mekhlafi, A.B.A. Safety-management practices and the occurrence of occupational accidents: Assessing the mediating role of safety compliance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Clarke, S.; Cooper, C.L. (Eds.) Occupational Health and Safety; Gower Publishing, Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J. Appl. Psyc. Olog. 2011, 96, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenke-Borgmann, L.; Digregorio, H.; Cantrell, M.A. Role clarity and interprofessional colleagues in psychological safety: A faculty reflection. Simul. Healthc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, J.K.; Yorio, P.L. A system of safety management practices and worker engagement for reducing and preventing accidents: An empirical and theoretical investigation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 68, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiken, L.G.; Shook, N.J. Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2011, 2, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, C. The influence of dispositional mindfulness on safety behaviors: A dual process perspective. Acci. Anal. Prev. 2014, 70, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahari, S.F. An Investigation of Safety Training, Safety Climate and Safety Outcomes: A Longitudinal Study in a Malaysian Manufacturing Plant; The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sawacha, E.; Naoum, S.; Fong, D. Factors affecting safety performance on construction sites. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1999, 17, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.G.; Cañamares, M.S.; Escribano, B.V.; Barriuso, A.R. Constructiońs health and safety Plan: The leading role of the main preventive management document on construction sites. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, B.; Albert, A.; Patil, Y.; Al-Bayati, A.J. Fostering safety communication among construction workers: Role of safety climate and crew-level cohesion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flin, R. Measuring safety culture in healthcare: A case for accurate diagnosis. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Lin, S.; Falwell, A.; Gaba, D.; Baker, L. Relationship of safety climate and safety performance in hospitals. Health Serv. Res. 2009, 44, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K.; Whitaker, S.M.; Flin, R. Safety climate, safety management practice and safety performance in offshore environments. Saf. Sci. 2003, 41, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.; Marchand, A. The behaviour of first-line supervisors in accident prevention and effectiveness in occupational safety. Saf. Sci. 1994, 17, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M. A study on the impact of management system certification on safety management. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.H.; Yiu, T.W.; González, V.A. Predicting safety behavior in the construction industry: Development and test of an integrative model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgheipour, H.; Eskandari, D.; Barkhordari, A.; Mavaji, M.; Tehrani, G.M. Predicting the relationship between safety climate and safety performance in cement industry. Work 2020, 66, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, M.D. Towards a model of safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2000, 36, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Stetzer, A. A cross-level investigation of factors influencing unsafe behaviors and accidents. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 307–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, M.F.; Santos, G.; Silva, R. A generic model for integration of quality, environment and safety management systems. TQM J. 2014, 26, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Tuuli, M.M.; Xia, B.; Koh, T.Y.; Rowlinson, S. Toward a model for forming psychological safety climate in construction project management. Inter. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.J.; Eskandari, D.; Valipour, F.; Mehrabi, Y.; Charkhand, H.; Mirghotbi, M. Development and validation of a new safety climate scale for petrochemical industries. Work 2017, 58, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, D.; Gharabagh, M.J.; Barkhordari, A.; Gharari, N.; Panahi, D.; Gholami, A.; Teimori-Boghsani, G. Development of a scale for assessing the organization’s safety performance based fuzzy ANP. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2021, 69, 104342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. The relationship between safety climate and safety performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imna, M.; Hassan, Z. Influence of human resource management practices on employee retention in Maldives retail industry. Int. J. Account. Bus. Manag. 2015, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhai, H.; Chan, A.H. Development of scales to measure and analyse the relationship of safety consciousness and safety citizenship behaviour of construction workers: An empirical study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Mullen, J.; Francis, L. Divergent effects of transformational and passive leadership on employee safety. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavik, A.; Bavik, y.L.; Tang, P.M. Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A. Creating safer workplaces: The role of ethical leadership. Saf. Sci. 2015, 73, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córcoles, M.; Gracia, F.; Tomás, I.; Peiró, J.M. Leadership and employees’ perceived safety behaviours in a nuclear power plant: A structural equation model. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, K.L.; Stock, G.N.; Gowen, C.R. Leadership, safety climate, and continuous quality improvement. J. Nurs. Admi. 2014, 44, S27–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarnati, J.T. Leaders as role models: 12 rules. Care. Dev. Inter. 2002, 7, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Chengang, Y.; Zhuo, S.; Manzoor, S.; Ullah, I.; Mughal, Y.H. Role of responsible leadership for organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in light of psychological ownership and employee environmental commitment: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 756570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Shahjehan, A.; Afridi, S.A.; Nawaz, A.; Fazliani, H. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peon, J.M.; Vazquez-Ordas, C.J. Safety management system: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. J. Loss Prev. Proc. Ind. 2007, 7, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Safety leadership, risk management and safety performance in Spanish firms. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C. Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership. In Responsible Leadership; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 885, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, T. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 2005; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Kapp, E.A. Ethical climates and workplace safety behaviors: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.K.M.; Man, S.S.; Chan, A.H.S. Exploring the acceptance of PPE by construction workers: An extension of the technology acceptance model with safety management practices and safety consciousness. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Yeo, S.K.; Go, S.S. A study on the improving safety management by analyzing safety consciousness of construction labors. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2009, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhong, L. Responsible leadership fuels innovative behavior: The mediating roles of socially responsible human resource management and organizational pride. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 787833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A. The COVID-19 pandemic and the role of responsible leadership in health care: Thinking beyond employee well-being and organisational sustainability. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2021, 34, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gond, J.P.; El-Akremi, A.; Igalens, J.; Swaen, V. Corporate social responsibility influence on employees. Int. Cent. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2010, 54, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

| Construct/Variable | βeta | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety Management | 0.973 | 0.975 | 0.740 | |

| SM1 | 0.775 | |||

| SM2 | 0.863 | |||

| SM3 | 0.866 | |||

| SM4 | 0.829 | |||

| SM5 | 0.831 | |||

| SM6 | 0.877 | |||

| SM7 | 0.833 | |||

| SM8 | 0.833 | |||

| SM9 | 0.778 | |||

| SM10 | 0.762 | |||

| SM11 | 0.787 | |||

| SM12 | 0.825 | |||

| SM13 | 0.853 | |||

| SM14 | 0.846 | |||

| SM15 | 0.862 | |||

| SM16 | 0.830 | |||

| SM17 | 0.780 | |||

| SM18 | ||||

| Safety Consciousness | 0.948 | 0.949 | 0.728 | |

| SC1 | 0.766 | |||

| SC2 | 0.843 | |||

| SC3 | 0.889 | |||

| SC4 | 0.858 | |||

| SC5 | 0.868 | |||

| SC6 | 0.895 | |||

| SC7 | 0.847 | |||

| Safety Climate | 0.959 | 0.960 | 0.774 | |

| SCL1 | 0.830 | |||

| SCL2 | 0.867 | |||

| SCL3 | 0.889 | |||

| SCL4 | 0.889 | |||

| SCL5 | 0.906 | |||

| SCL6 | 0.897 | |||

| SCL7 | 0.880 | |||

| Responsible Leadership | 0.903 | 0.907 | 0.662 | |

| RL1 | 0.744 | |||

| RL2 | 0.841 | |||

| RL3 | 0.886 | |||

| RL4 | 0.834 | |||

| RL5 | 0.753 | |||

| Safety Performance | 0.948 | 0.949 | 0.728 | |

| SP1 | 0.848 | |||

| SP2 | 0.864 | |||

| SP3 | 0.862 | |||

| SP4 | 0.831 | |||

| SP5 | 0.859 | |||

| SP6 | 0.819 | |||

| SP8 | 0.887 | |||

| Goodness of fit indices | ||||

| χ2 = 1482; d.f. = 845; χ2/d.f. = 1.75; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.93; GFI = 0.76; AGFI = 0.73; RMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.06 | ||||

| Variable | No of Items | Mean | s.d. | SM | SC | SCL | RL | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SM | 17 | 3.84 | 0.88 | 0.740 | ||||

| 2 | SC | 7 | 3.15 | 1.04 | 0.241 ** (0.058) | 0.728 | |||

| 3 | SCL | 7 | 3.44 | 1.06 | 0.159 * (0.025) | 0.800 ** (0.640) | 0.774 | ||

| 4 | RL | 5 | 2.93 | 1.01 | 0.005 (0.0002) | 0.233 ** (0.054) | 0.181 ** (0.033) | 0.662 | |

| 5 | SP | 7 | 3.91 | 0.89 | 0.024 (0.0005) | 0.343 ** (0.1180 | 0.431 ** (0.186) | −0.286 ** (0.082) | 0.728 |

| Path | Estimate | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM→SP (Direct Effect) | −0.0641 | 0.07 | ||

| SM→SC | 0.285 * | 0.08 | ||

| SC→SP | 0.310 * | 0.06 | ||

| Standardized Direct and Indirect Effects using 5000 Bootstrap 95% CI | ||||

| Path | Effect | SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

| Direct Effect | −0.641 | 0.07 | −0.199 | 0.071 |

| Indirect Effect (SM→SC→SP) | 0.086 * | 0.04 | 0.025 | 0.164 |

| Path | Estimate | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM→SP (Direct Effect) | −0.047 | 0.06 | ||

| SM→SCL | 0.192 * | 0.08 | ||

| SCL→SP | 0.371 * | 0.05 | ||

| Standardized Direct and Indirect Effects using 5000 Bootstrap 95% CI | ||||

| Path | Effect | SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

| Direct Effect | −0.047 | 0.06 | −0.175 | 0.081 |

| Indirect Effect (SM→SCL→SP) | 0.069 * | 0.04 | 0.066 | 0.144 |

| DV: SP | DV: SP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | Estimate | SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | |

| SC | 0.241 * | 0.055 | 0.131 | 0.351 | ||||

| RL | 0.174 * | 0.057 | 0.061 | 0.287 | ||||

| SC*RL | −0.163 * | 0.057 | −0.265 | −0.061 | ||||

| SCL | 0.302 * | 0.053 | 0.196 | 0.407 | ||||

| RL | 0.186 * | 0.054 | 0.078 | 0.293 | ||||

| SCL*RL | −0.117 ** | 0.048 | −0.212 | −0.022 | ||||

| Model Fit | ||||||||

| F-value | 17.22 * | 23.02 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.25 | ||||||

| R2 Change | 0.04 * | 0.02 ** | ||||||

| Path | Estimate | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM→SP (conditional direct Effect) | −0.025 | 0.06 | ||

| SM→SC | 0.285 * | 0.08 | ||

| SC→SP | 0.247 * | 0.06 | ||

| RL→SP | 0.1730 * | 0.06 | ||

| RL*SC→SP | −0.161 * | 0.05 | ||

| SM→SP (conditional direct Effect) | −0.016 | 0.06 | ||

| SM→SCL | 0.3045 * | 0.05 | ||

| SCL→SP | 0.192 ** | 0.08 | ||

| RL→SP | 0.1856 * | 0.05 | ||

| RL*SCL→SP | −0.167 ** | 0.07 | ||

| Conditional indirect effects of X on Y in presence of moderator using 5000 bootstrap 95% CI | ||||

| Path | Effect | SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

| SA→SC→SP | 0.4096 * | 0.07 | 0.263 | 0.556 |

| SA→SCL→SP | 0.4214 * | 0.06 | 0.296 | 0.547 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saleem, F.; Malik, M.I. Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013686

Saleem F, Malik MI. Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013686

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaleem, Farida, and Muhammad Imran Malik. 2022. "Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013686

APA StyleSaleem, F., & Malik, M. I. (2022). Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13686. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013686