“To Be Treated as a Person and Not as a Disease Entity”—Expectations of People with Visual Impairments towards Primary Healthcare: Results of the Mixed-Method Survey in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Primary Health Care in Poland

1.2. Disabilities, including Visual Impairments, and Health Situation

1.3. Patients’ Expectations—Earlier Studies and a Gap in PVIs Surveying

1.4. Objectives

- assess the general level of PVIs’ expectations towards the Accessibility, Continuity, Equity, and Quality of PHC;

- determine if PVIs’ sociodemographic, health, and disability characteristics are associated with the level of their expectations towards the abovementioned PHC dimensions;

- identify aspects of PHC considered as the most important by PVIs;

- compare expectations of poor-sighted and blind people towards PHC;

- establish expectations of PVIs related to the specificity of functioning with blindness and low vision in PHC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Socio-Demographic, Disability, and Health Characteristics

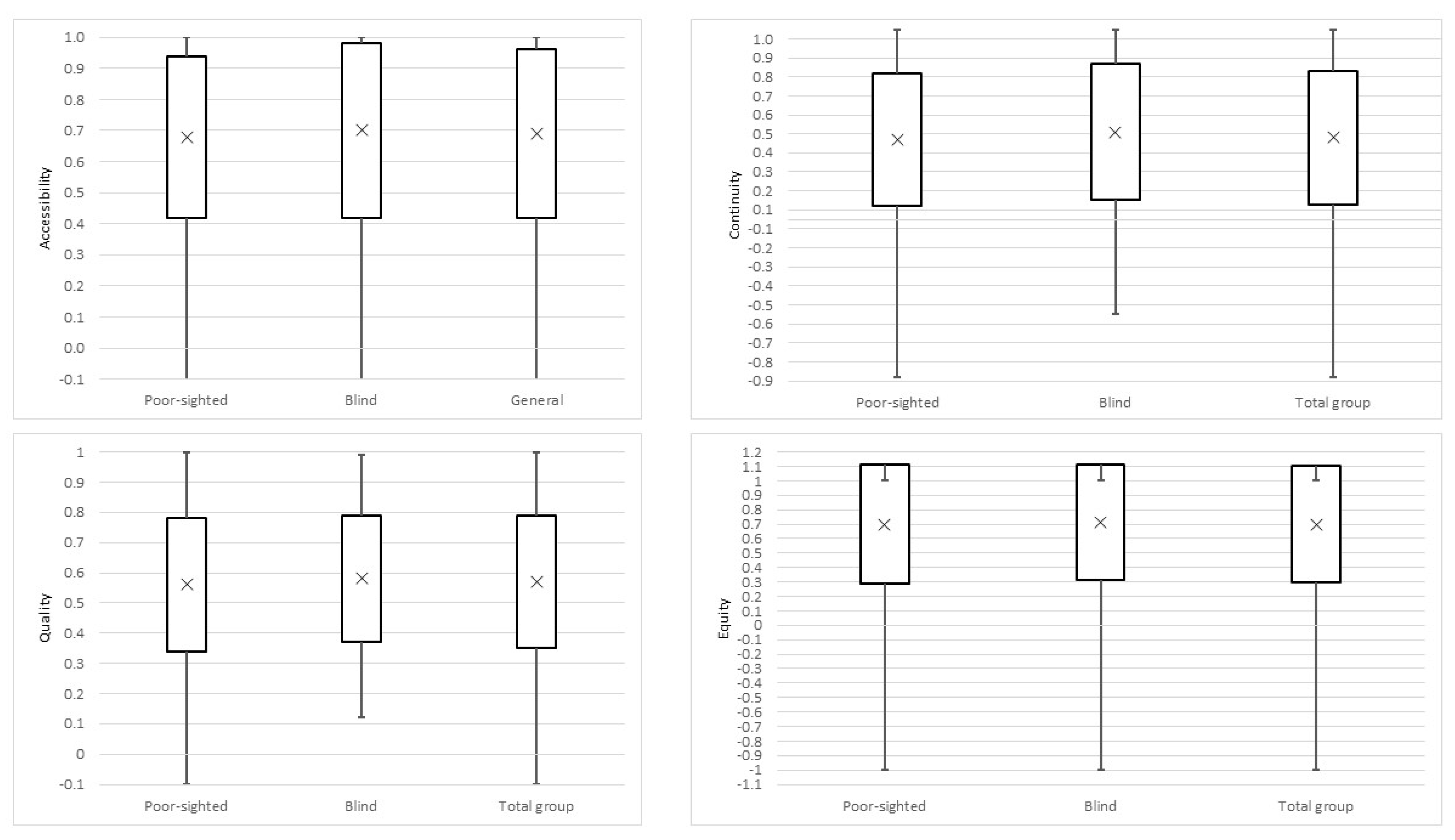

3.2. General Levels of PVIs Expectations towards the Main Dimensions of PHC

3.3. PVIs Characteristics and Expectations towards Four PHC Dimensions

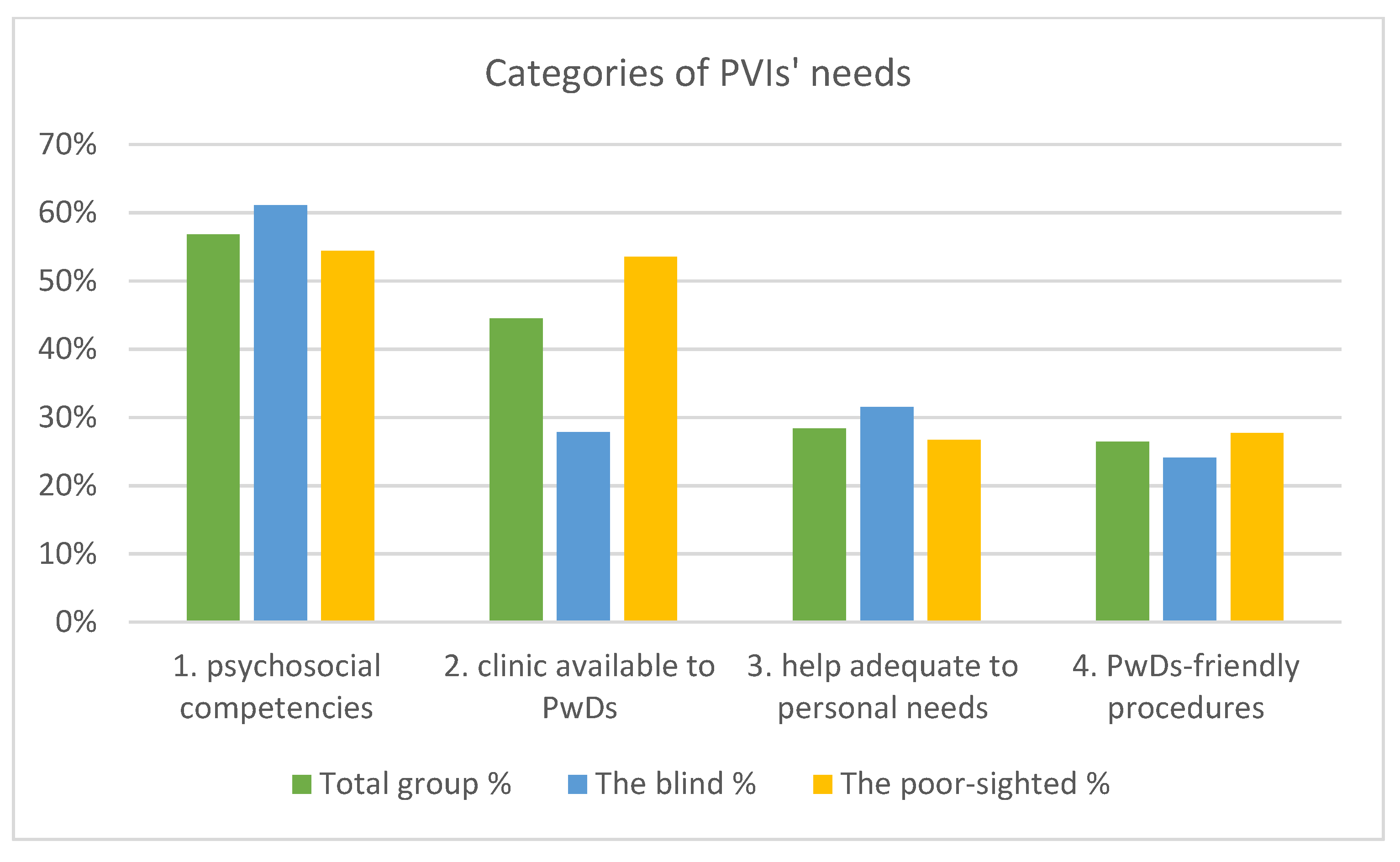

3.4. Hierarchy of PHC Values including the Level of Respondents’ VI

3.5. PVIs Expectations towards PHC—Voice of Respondents

“I recommend more cooperation with nongovernmental organizations working for PwDs, audits of architectural, communication and information accessibility. In addition to staff training and mystery clients with disabilities, social campaigns should be organized and employees of PHC should be controlled suddenly and unannounced.”

“For me, independence is very important and I don’t like the confusion that an appearance of a person with a white cane causes. I would prefer to be independent of the lady at the front desk, reception desk or security when I need to find the office or reception desk.”

“I am satisfied with my primary care clinic—the people working there know me, they know about my disability, they help me in organizational matters, e.g., they drive me to the office, they watch my queue, they call me a cab after my visit.”

“inform patients what preventive examinations should be done, at what age and what is the closest locations for such examinations” and “take care of the same patients, because he knows them and their situation.”

“During the visit [it is important] that the doctor does not rush you, informs you exactly what is going to be done and how it is going to be done, e.g., examination, gives you the opportunity to feel the examination area, e.g., the place of the recliner and does not rush you to do it. And after the visit, the patient should be able to contact the doctor by phone or in person at any time during the treatment course.”

“It is also more difficult to weed out all sorts of questionnaires, statements, and documents on the spot. Thus, it is important that they be available in the electronic version and can be filled out before the visit.”

“The doctor who has written out documents to ZUS [Zakład Ubezpieczeń Społecznych, The Social Insurance Institution] should send them by e-mail so that the person with disabilities does not have to visit many specialists (e.g., ophthalmologist, neurologist, orthopedist, and finally ZUS).”

“I believe that it is highly important to design procedures which would make it easier for blind people to receive treatment at the primary care level, use specialized care, rehabilitation and sanatoriums.”

4. Discussion

4.1. The Highest and the Lowest Valued PHC Dimensions by PVIs

4.2. PVIs Characteristics Associated with Their Expectations towards PHC Dimensions

4.3. The Most Valuable Aspects of PHC for PVIs Measured with PVQ

4.4. PVIs Voice about Their Needs When Using PHC

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. Declaration of Astana, Proceedings of the Global Conference on Primary Health Care from Alma-Ata towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals, Astana, Kazakhstan, 25–26 October 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Ustawa z 27.10.2017 r. o Podstawowej Opiece Zdrowotnej (Dz. U. 2017. poz. 2217). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170002217 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Statistics Poland. Health Status of Population in Poland in 2019. Warsaw 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/stan-zdrowia-ludnosci-polski-w-2019-r-,6,7.html (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Statistics Poland & Statistical Office in Kraków. Health and Health Care in 2020. Warszawa, Kraków 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/zdrowie-i-ochrona-zdrowia-w-2020-roku,1,11.html (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Ministerstwo Zdrowia; Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia; Departament Obsługi Pacjenta. Raport z Badania Satysfakcji Pacjentów Korzystających z Teleporad u Lekarza Podstawowej Opieki Zdrowotnej w Okresie Epidemii COVID-19; Report on Patient Satisfaction with Primary Care Physician Telehealth during the COVID-19 Epidemic; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Primary Health Care Measurement Framework and Indicators: Monitoring Health Systems through A Primary Health Care Lens; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240044210 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Konwencja o prawach osób niepełnosprawnych. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Dz.U. 2012 poz. 1169). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20120001169 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Kuper, H.; Mactaggart, I.; Dionicio, C.; Cañas, R.; Naber, J.; Polack, S. Can we achieve universal health coverage without a focus on disability? Results from a national case-control study in Guatemala. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization and the World Bank. World Report on Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 77–79. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Senjam, S.S.; Singh, A. Addressing the health needs of people with disabilities in India. Indian J. Public Health 2020, 64, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Campos, V.; Cartes-Velásquez, R. Estado actual de la atención sanitaria de personas con discapacidad auditiva y visual: Una revisión breve; Health care of people with visual or hearing disabilities. Rev. Med. Chil. 2019, 147, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupples, M.E.; Hart, P.M.; Johnston, A.; Jackson, A.J. Improving healthcare access for people with visual impairment and blindness. BMJ 2012, 344, e542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, C.; Frick, K.; Gower, E.W.; Kempen, J.H.; Wolff, J.L. Disparities in access to medical care for individuals with vision impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009, 16, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.M.; Wright, S.M. Severe vision impairment and blindness in hospitalized patients: A retrospective nationwide study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021, 21, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Spuling, S.M.; Heyl, V. Associations of self-reported vision problems with health and psychosocial functioning: A 9-year longitudinal perspective. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2021, 39, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, J.E.; Chou, C.F.; Sekar, S.; Saaddine, J.B. The prevalence of chronic conditions and poor health among people with and without vision impairment, aged ≥65 years, 2010–2014. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 182, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, H.; McLean, G.; Guthrie, B.; Mercer, S.W.; Smith, D.J. Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental comorbidities in older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Liljas, A.E.M. The relationship between self-reported sensory impairments and psychosocial health in older adults: A 4-year follow-up study using the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Public Health 2019, 169, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, J.E.; Chou, C.F.; Zack, M.M.; Zhang, X.; Bullard, K.M.; Morse, A.R.; Saaddine, J.B. The association of health-related quality of life with severity of visual impairment among people aged 40–64 years: Findings from the 2006–2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016, 23, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanefeld, J.; Powell-Jackson, T.; Balabanova, D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: Dealing with complexity. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, W.L.; Boerma, W.G.; Kringos, D.S.; De Maeseneer, J.; Gress, S.; Heinemann, S.; Rotar-Pavlic, D.; Seghieri, C.; Svab, I.; Van den Berg, M.J.; et al. QUALICOPC, a multi-country study evaluating quality, costs and equity in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszczyk, M.A. Jakość Podstawowej Opieki Zdrowotnej w Polsce w Ocenie Pacjentów. Quality of Primary Health Care in Poland as Perceived by Patients. Doctoral Dissertation, Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków, Poland, 2014. Available online: http://dl.cm-uj.krakow.pl:8080/dlibra/publication/3952/edition/3952?language=pl (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Krztoń-Królewiecka, A.; Oleszczyk, M.; Windak, A. Do Polish primary care physicians meet the expectations of their patients? An analysis of Polish QUALICOPC data. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K.; Sawicka, A. Analiza oczekiwań pacjentów objętych ambulatoryjną opieką medyczną w Podstawowej Opiece Zdrowotnej; Analysis of the patients expectations covered by the outpatient medical care in primary health care. Forum Med. Rodz. 2016, 10, 263–271. Available online: https://journals.viamedica.pl/forum_medycyny_rodzinnej/article/view/49640 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Alraddadi, K.S.; Al-Adwani, F.; Taher, Z.A.; Al-Mansour, M.; Khan, M. Factors influencing patients’ preferences for their treating physician. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.P.; Baerveldt, C.; Olesen, F.; Grol, R.; Wensing, M. Patient characteristics as predictors of primary health care preferences: A systematic literature analysis. Health Expect. 2003, 6, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, M.; Rzadkiewicz, M.; Adamus, M.; Chylinska, J.; Lazarewicz, M.; Haugan, G.; Lillefjell, M.; Espnes, G.A.; Wlodarczyk, D. Primary care patients’ expectations regarding medical appointments and their experiences during a visit: Does age matter? Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instytut Tyflologiczny Polskiego Związku Niewidomych. Raport Wydany w Ramach Projektu “Widzimy nie Tylko Oczami”; The Report Released as Part of the “We See with More Than Just Our Eyes” Project; EPEdruk Sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://pzn.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Raport-Widzimy-nie-tylko-oczam.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2014/en#/H54 (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Skiba, P. Niewidomy, Ociemniały, Słabowidzący, Tracący Wzrok. Definicje, Różnice; Polish Association of the Blind: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; Available online: https://pzn.org.pl/niewidomy-ociemnialy-slabowidzacy-tracacy-wzrok-definicje-roznice/ (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Schäfer, W.L.; Boerma, W.G.; Kringos, D.S.; De Ryck, E.; Greß, S.; Heinemann, S.; Murante, A.M.; Rotar-Pavlic, D.; Schellevis, F.G.; Seghieri, C.; et al. Measures of quality, costs and equity in primary health care instruments developed to analyse and compare primary care in 35 countries. Qual. Prim. Care 2013, 21, 67–79. Available online: https://www.primescholars.com/articles/measures-of-quality-costs-and-equity-in-primary-health-care-instruments-developed-to-analyse-and-compare-primary-health-care-in-35-countries.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Stanisz, A. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL na Przykładach z Medycyny. Tom 1. Statystyki Podstawowe; An Affordable Statistics Course with Applications of STATISTICA PL on Examples from Medicine; StatSoft: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Volume 1, Basic Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cathain, A.; Thomas, K.J. Any other comments? Open questions on questionnaires—A bane or a bonus to research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2004, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej The Constitution of the Republic of Poland. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/polski/kon1.htm (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Czauderna, P.; Gałązka-Sobotka, M.; Górski, P.; Hryniewiecki, T. Strategiczne Kierunki Rozwoju Systemu Ochrony Zdrowia w Polsce; Strategic Directions of Health Care System Development in Poland; Ministerstwo Zdrowia: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; Available online: http://oipip.elblag.pl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Wsp%C3%B3lnie-dla-zdrowia_dokument-podsumowuj%C4%85cy.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Tomczyk, U. Raport Tematyczny nt. Wdrażania art. 25 ”Zdrowie” Opracowany w Ramach Projektu “Wdrażanie Konwencji o Prawach osób Niepełnosprawnych—Wspólna Sprawa”. Thematic Report on the Implementation of Article 25 “Health” Developed within the Framework of the Project “Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—A Common Cause”. 2017. Available online: https://www.dzp.pl/files/shares/Publikacje/Raport_tematyczny_art.25.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Wołoszyn-Cichocka, A. Konstytucyjny obowiązek zapewnienia szczególnej opieki zdrowotnej dzieciom, kobietom ciężarnym, osobom niepełnosprawnym i osobom w podeszłym wieku przez władze publiczne. Constitutional Duty of Providing High-Quality Health Care for Children, Pregnant Women, Disabled People and Elderly People by Public Authorities. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. G-Ius 2017, 64, 225–241. Available online: https://journals.umcs.pl/g/article/view/5009 (accessed on 6 June 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Day, B.L.; Killeen, M.; Iezzoni, L.I. Improving health care experiences of persons who are blind or have low vision: Suggestions from focus groups. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2004, 19, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droz, M.; Senn, N.; Cohidon, C. Communication, continuity and coordination of care are the most important patients’ values for family medicine in a fee-for-services health system. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, P.; De Abreu Lourenco, R.; Wong, C.Y.; Haas, M.; Goodall, S. Community preferences in general practice: Important factors for choosing a general practitioner. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violan, C.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Flores-Mateo, G.; Salisbury, C.; Blom, J.; Freitag, M.; Glynn, L.; Muth, C.; Valderas, J.M. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: A systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Díez, J.M.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Poncel-Falcó, A.; Poblador-Plou, B.; Calderón-Meza, J.M.; Sicras-Mainar, A.; Clerencia-Sierra, M.; Prados-Torres, A. Age and gender differences in the prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in the older population. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nánási, A.; Ungvári, T.; Kolozsvári, L.R.; Harsányi, S.; Jancsó, Z.; Lánczi, L.I.; Mester, L.; Móczár, C.; Semanova, C.; Schmidt, P.; et al. Expectations, values, preferences and experiences of Hungarian primary care population when accessing services: Evaluation of the patient’s questionnaires of the international QUALICOPC study. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertakis, K.D. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 76, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, H.; Baker, M. Continuity of care: Still important in modern-day general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, 396–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkelmans, P.G.; Berendsen, A.J.; Verhaak, P.F.; van der Meer, K. Characteristics of general practice care: What do senior citizens value? A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, D. Multimorbidity in the Elderly: A Systematic Bibliometric Analysis of Research Output. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, K.; Pac, A.; Skalska, A.; Mossakowska, M.; Chudek, J.; Zdrojewski, T.; Więcek, A.; Grodzicki, T.; Gąsowski, J. Patterns of multimorbidity in 4588 older adults: Implications for a nongeriatrician specialist. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2021, 131, 16128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mold, J.W.; Fryer, G.E.; Roberts, A.M. When do older patients change primary care physicians? J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2004, 17, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Tarrant, C.; Windridge, K.; Bryan, S.; Boulton, M.; Freeman, G.; Baker, R. Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2007, 12, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, L.L.; Parish, J.T.; Janakiraman, R.; Ogburn-Russell, L.; Couchman, G.R.; Rayburn, W.L.; Grisel, J. Patients’ commitment to their primary physician and why it matters. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobów, T. Przestrzeganie zaleceń medycznych przez pacjentów w wieku podeszłym; Adherence to medication among elderly patients. Postępy Nauk. Med. 2011, XXIV, 8. Available online: http://www.pnmedycznych.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pnm_2011_682_687.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Drainoni, M.-L.; Lee-Hood, E.; Tobias, C.; Bachman, S.S.; Andrew, J.; Maisels, L. Cross-Disability Experiences of Barriers to Health-Care Access: Consumer Perspectives. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2006, 17, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, N.; Södergård, B. Access to Healthcare among People with Physical Disabilities in Rural Louisiana. Soc. Work Public Health 2016, 31, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, V.S.; Burman, M.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D. Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Freeman, G.K.; Haggerty, J.L.; Bankart, M.J.; Nockels, K.H. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e600–e611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, D.J.P.; Sidaway-Lee, K.; White, E.; Thorne, A.; Evans, P.H. Continuity of care with doctors—A matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlenk-Czyczerska, E.; Guzek, M.; Bielska, D.E.; Ławnik, A.; Polański, P.; Kurpas, D. The Analysis of the Relationship between the Quality of Life Level and Expectations of Patients with Cardiovascular Diseases under the Home Care of Primary Care Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionis, C.; Papadakis, S.; Tatsi, C.; Bertsias, A.; Duijker, G.; Mekouris, P.B.; Boerma, W.; Schäfer, W.; Greek QUALICOPC Team. Informing primary care reform in Greece: Patient expectations and experiences (the QUALICOPC study). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batbaatar, E.; Dorjdagva, J.; Luvsannyam, A.; Savino, M.M.; Amenta, P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A systematic review. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, T.B.; Straand, J.; Braend, A.M. Good communication was valued as more important than accessibility according to 707 Nordic primary care patients: A report from the QUALICOPC study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2021, 39, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, N.; Morera, O.; Frankowski, S. Developing a measure of blind patients’ interactions with their healthcare providers. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.H.; George, V.; Mosqueda, L. Primary care for adults with physical disabilities: Perceptions from consumer and provider focus groups. Fam. Med. 2008, 40, 645–651. Available online: https://fammedarchives.blob.core.windows.net/imagesandpdfs/fmhub/fm2008/October/Elizabeth645.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Sharts-Hopko, N.C.; Smeltzer, S.; Ott, B.B.; Zimmerman, V.; Duffin, J. Healthcare experiences of women with visual impairment. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2010, 24, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaronnik, N.; Campbell, E.G.; Ressalam, J.; Iezzoni, L.I. Communicating with patients with disability: Perspectives of practicing physicians. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N. Understanding of how older adults with low vision obtain, process, and understand health information and services. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2019, 44, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, V.; Cartes-Velásquez, R. Developing competencies for the dental care of people with sensory disabilities: A pilot inclusive approach. Cumhur. Dent. J. 2020, 23, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder-Olibrowska, K.W.; Wrzesińska, M.A.; Godycki-Ćwirko, M. Is Telemedicine in Primary Care a Good Option for Polish Patients with Visual Impairments Outside of a Pandemic? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder-Olibrowska, K. Telemedycyna a niepełnosprawność wzrokowa–szanse, zagrożenia, wyzwania; Telemedicine and visual impairment—Opportunities, threats, challenges. In Wirtualizacja Życia Osób z Niepełnosprawnością; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.; van Royen, P.; Baker, R. Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2002, 11, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinowicz, L.; Chlabicz, S.; Grebowski, R. Open-ended questions in surveys of patients’ satisfaction with family doctors. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2007, 12, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semyonov-Tal, K.; Lewin-Epstein, N. The importance of combining open-ended and closed-ended questions when conducting patient satisfaction surveys in hospitals. Health Policy Open 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasik, J.; Mróz, A. Jakość Życia i Sposób Funkcjonowania osób Niepełnosprawnych w Szpitalu A Zarządzanie Informacją. Quality of Life and How People with Disabilities Function in the Hospital Versus Information Management. Available online: http://idn.org.pl/lodz/Mken/MKEN%202003/referaty/Dr%20J%C3%B3zef%20Jasik%20pop.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Ordway, A.; Garbaccio, C.; Richardson, M.; Matrone, K.; Johnson, K.L. Health care access and the Americans with Disabilities Act: A mixed methods study. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 14, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Long-Bellil, L.M. Training physicians about caring for persons with disabilities: “Nothing about us without us!”. Disabil. Health J. 2012, 5, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaronnik, N.; Campbell, E.G.; Ressalam, J.; Iezzoni, L.I. Exploring issues relating to disability cultural competence among practicing physicians. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshblum, S.; Murray, R.; Potpally, N.; Foye, P.M.; Dyson-Hudson, T.; DallaPiazza, M. An introductory educational session improves medical student knowledge and comfort levels in caring for patients with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Agaronnik, N.D. Healthcare Disparities for Individuals with Disability: Informing the Practice. In Disability as Diversity; Meeks, L., Neal-Boylan, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Rao, S.R.; Ressalam, J.; Bolcic-Jankovic, D.; Agaronnik, N.D.; Donelan, K.; Lagu, T.; Campbell, E.G. Physicians’ Perceptions of People with Disability and Their Health Care. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A.R.; Polsunas, P.; Borecky, K.; Brane, L.; Day, J.; Ferber, G.; Harris, K.; Hickman, C.; Olsen, J.; Sherrier, M.; et al. Reaching for equitable care: High levels of disability-related knowledge and cultural competence only get us so far. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 11, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleij, K.S.; Tangermann, U.; Amelung, V.E.; Krauth, C. Patients’ preferences for primary health care—A systematic literature review of discrete choice experiments. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaźmierczak, D.; Bogusz-Czerniewicz, M. Identification of patient’s requirements in quality management system in health care institutions. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2011, 17, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schäfer, W.L.; Boerma, W.G.; Murante AMSixma, H.J.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P.P. Assessing the potential for improvement of primary care in 34 countries: A cross-sectional survey. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, N.; Olumolade, O.; Aittama, M.; Samoray, O.; Khan, M.; Wasserman, J.A.; Weber, K.; Ragina, N. Access barriers to healthcare for people living with disabilities. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, P.; Babicki, M.; Krawczyk, J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. War in Ukraine and the challenges it brings to the Polish healthcare system. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 15, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishori, R.; Aleinikoff, S.; Davis, D. Primary Care for Refugees: Challenges and Opportunities. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 112–120. Available online: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0715/p112.html (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Sackey, D.; Jones, M.; Farley, R. Reconceptualising specialisation: Integrating refugee health in primary care. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2020, 26, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accessibility | Continuity | Quality of Care | Equity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Overall | 0.69 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.40 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 0.72 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.37 |

| Male | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.37 a | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.44 b |

| Gender in the poor-sighted group | ||||||||

| Female | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.74 | 0.37 |

| Male | 0.61 | 0.32 c | 0.32 | 0.32 d | 0.50 | 0.25 e | 0.61 | 0.45 f |

| Gender in the blind group | ||||||||

| Female | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.77 | 0.35 |

| Male | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.66 | 0.43 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–39 | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| 40–59 | 0.66 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.75 | 0.35 |

| 60 and more | 0.72 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.31 g | 0.61 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.35 |

| Place of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.40 |

| Urban to 50 k of inhabitants | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.40 |

| Urban from 50 k to 100 k of inhabitants | 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.35 |

| Urban from 100 k to 500 k of inhabitants | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.31 |

| Urban over 500 k of inhabitants | 0.74 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.48 |

| Education level | ||||||||

| Primary | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.61 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.38 |

| Secondary | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.39 |

| Higher | 0.65 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 0.43 |

| Level of disability | ||||||||

| Poor-sighted | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.41 |

| The blind | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.71 | 0.40 |

| Subjective health status | ||||||||

| Very good | 0.70 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.77 | 0.37 |

| Good | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.23 | 0.60 | 0.50 |

| Average | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.33 |

| Poor | 0.66 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 0.81 | 0.25 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.37 |

| No | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.37 h | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.46 |

| Other disability than VI | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.36 |

| No | 0.69 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.43 |

| Quality of life | ||||||||

| Very poor and poor | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.42 |

| Average | 0.68 | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.59 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.43 |

| Good | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.40 |

| Very good | 0.79 | 0.21 i | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.73 | 0.35 |

| Assistant of PwD | ||||||||

| Often | 0.75 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.76 | 0.37 |

| Seldom | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.49 |

| Never | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.20 j | 0.73 | 0.37 |

| Moving around with help | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.69 | 0.44 |

| No | 0.63 | 0.29 k | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.73 | 0.30 |

| Total Group n = 219 | Poor-Sighted n = 156 | Blind n = 63 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Important | Rather Not Important | Important | Very Important | Very Important | ||

| Accessibility | ||||||

| I can get appointment easily | 0.5 | 0.5 | 27.4 | 71.6 | 68.6 | 79.4 |

| Short waiting time on the phone | - | 1.4 | 34.2 | 64.4 | 66.0 | 60.3 |

| I know how to seek health services at night or weekend | 0.9 | 4.6 | 37.0 | 57.5 | 56.4 | 60.3 |

| PHC clinic is close to where I live or work | 1.8 | 11.4 | 38.8 | 48.0 | 44.9 | 55.6 |

| PHC clinic has long opening hours | 3.7 | 15.1 | 47.9 | 33.3 | 32.1 | 36.5 |

| Continuity | ||||||

| PCP has access to prior medical records | 0.9 | 4.6 | 35.1 | 59.4 | 58.3 | 61.9 |

| PCP is aware of my medical history | - | 4.6 | 51.1 | 44.3 | 41.7 | 50.8 |

| PCP knows about my living situation | 17.8 | 40.6 | 29.2 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 14.3 |

| Quality of care | ||||||

| socio-emotional behaviors | ||||||

| I understand what the PCP explains | - | 0.9 | 21.9 | 77.2 | 73.7 | 85.7 |

| I feel more comfortable to manage my medical problem after visit | 0.4 | 3.2 | 47.5 | 48.9 | 45.5 | 57.1 |

| PCP is polite | - | 2.7 | 43.4 | 53.9 | 50.6 | 61.9 |

| People working at reception desk are polite and helpful | - | 3.2 | 32.9 | 63.9 | 60.9 | 71.4 |

| PCP asks about my health problem | - | 1.4 | 37.0 | 61.6 | 57.7 | 71.4 |

| PCP asks about other patients’ problems | 0.4 | 8.2 | 48.9 | 42.5 | 37.8 | 54.0 a |

| preparation for consultation | ||||||

| I keep to my appointment | 0.9 | 1.4 | 38.8 | 58.9 | 60.0 | 57.1 |

| I know which PCP I will see | 3.7 | 5.0 | 42.9 | 48.4 | 48.7 | 47.6 |

| It is not neccessary to tell a receptionist or nurse about details of my health problem before seeing my doctor | 3.2 | 13.2 | 47.5 | 36.0 | 35.9 | 36.5 |

| PCP knows my medical background | 1.4 | 9.6 | 46.6 | 42.5 | 39.7 | 49.2 |

| I can bring my family/friends/assistant to the consultation | 11.9 | 20.5 | 40.6 | 27.0 | 24.4 | 33.3 |

| I have prepared for the visit, prepared a list of my symptoms and possible questions | 4.1 | 28.3 | 44.7 | 22.4 | 20.7 | 27.0 |

| during medical consultation with PCP | ||||||

| I do not feel pressure of time | - | 3.7 | 45.2 | 51.1 | 49.4 | 55.6 |

| PCP listens attentively | - | 0.5 | 35.6 | 63.9 | 57.7 | 79.4 b |

| PCP takes me seriously | 0.4 | 0.9 | 26.9 | 71.7 | 73.7 | 66.7 |

| PCP understands me well | - | 0.5 | 37.4 | 62.1 | 63.5 | 58.7 |

| PCP is respectful during physical examination and does not interrupt me | - | 2.3 | 32.4 | 65.3 | 62.2 | 73.0 |

| PCP knows when to refer | - | - | 24.7 | 75.3 | 76.3 | 73.0 |

| PCP treats me as a person, not just medical problem | - | 1.8 | 37.0 | 61.2 | 58.3 | 68.3 |

| I am honest and do not feel embarassed | - | 2.7 | 41.6 | 55.7 | 51.9 | 65.1 |

| PCP asks if I have understood everything | 0.4 | 7.8 | 47.5 | 44.3 | 44.2 | 44.4 |

| PCP aks if I have questions | - | 8.2 | 52.5 | 39.3 | 37.8 | 43.9 |

| PCP makes eye contact | 14.6 | 17.8 | 45.2 | 22.4 | 24.4 | 17.5 |

| PCP asks how I prefer to be treated | 2.3 | 14.6 | 47.0 | 36.1 | 34.6 | 39.7 |

| PCP avoids disturbance by call, etc. | 1.4 | 10.5 | 52.5 | 35.6 | 33.3 | 41.3 |

| PCP is not prejudiced (age, gender, religion, culture, disability) | 1.4 | 10.5 | 36.5 | 51.6 | 51.3 | 52.4 |

| I am open to talk about the use of other treatments | 13.7 | 24.2 | 41.1 | 21.0 | 20.5 | 22.2 |

| PCP gives me additional info about health problem | 9.1 | 26.0 | 40.7 | 24.2 | 22.4 | 28.6 |

| I am prepared to ask quesitons and take notes | 9.1 | 29.7 | 38.4 | 22.8 | 21.8 | 25.4 |

| I tell the PCP what I want to discuss in the consultation | 1.3 | 11.0 | 58.0 | 29.7 | 27.6 | 34.9 |

| Psychosocial problems can be discussed | 23.7 | 36.1 | 27.4 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 14.3 |

| PCP informs me about reliable source of information e.g., websites | 15.1 | 29.2 | 34.2 | 21.5 | 16.7 | 33.3 c |

| PCP is aware of my personal and socio-cultural background | 12.8 | 26.0 | 38.8 | 22.4 | 22.4 | 22.2 |

| After the consultation with PCP | ||||||

| I have clear instructions from PCP what to do when things go wrong | 0.5 | 1.4 | 26.0 | 72.1 | 73.1 | 69.8 |

| I adhere to agreed treatment | - | 4.6 | 41.5 | 53.9 | 52.6 | 57.1 |

| I inform the PCP how the treatment goes | 1.4 | 6.9 | 47.9 | 43.8 | 44.2 | 42.9 |

| I can see another PCP if I think it is necessary | 1.4 | 12.8 | 41.6 | 44.3 | 44.2 | 44.4 |

| PCP offers telephone or mail contact in case of further questions | 2.3 | 13.7 | 50.2 | 33.8 | 34.6 | 31.8 |

| PCP gives me all test results | 5.0 | 6.8 | 40.6 | 47.6 | 50.6 | 39.7 |

| Equity | ||||||

| PCP involves me in decision making | 0.9 | 5.0 | 41.6 | 52.5 | 52.6 | 52.4 |

| Non-Verbal Aspects of Communication |

|---|

| An eye contact “I will feel that the doctor is discounting me unless he looks at my eyes.” |

| Touch “I have a very good PCP doctor—when he says “good morning” to me he shakes my hand or touches my shoulder—then I know he is talking to me.” |

| Voice messages and their quality “(…) I remember one appointment I went to with my wife. The doctor did not speak at all until I had to ask my wife if the doctor was in the office. But he was. After that, he started to speak.” “[it is important] for the doctor to speak carefully. People with good vision do not realize that eye contact during a conversation plays a big role in understanding what the speaker is saying (…).” “I read the other person’s lips so the current situation where the doctor wears a mask at the appointment [in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic] is uncomfortable for me, I don’t often understand, the sound then is also different and I ask the doctor to repeat”(deaf-blind woman). |

| Communication through written words—PVIs need: “PCP to print out all information on a computer in black and white rather than write it down on a piece of paper by hand.” “PCP to fully explain the treatment procedure and clearly write (or print) the dosage and names of medications taken during the treatment.” “Well done website and detailed description.” |

| Medical staff attitude toward patients with VIs |

| Equal treatment by direct communication “I wish doctors would talk to us—the blind and not ignore us and instead talk about us to the person we came with. When I am at the doctor’s with my son—I can understand it, but if I am with an assistant—I cannot stand it. They treat us as if we are mentally handicapped, as if we have mental limitations. I feel like an invalid patient, it’s embarrassing and humiliating. Assistants do not want to enter the office with us, so that we are not treated in such a way. When we are left alone with the doctors, they have no choice but talk to us. But this is not a solution either. If I have a lot of different documents on me and I do not know which ones I am supposed to hand in and, in which order, I need such a person [an assistant of PwDs]. Doctors should learn how to treat patients who are poor-sighted or blind; after all, they have psychology classes as part of their studies.” |

| Serious, empathetic and not indulgent treatment of the patient “I once heard from a doctor <<Thousands of people live with such myopia>>. It was not pleasant, it took me a long time to come to terms with it and such a message was not helpful.” “(…) it is important that a person with visual impairment be treated normally and equally well as other patients. This refers not only to discrimination but excessive attention, signs of pity.” |

| Focus on the current patient’s problem and not on the disability “(…) the doctor should concentrate on the matter with which the patient came, and not ask about the reason why he lost their eyesight and not be disappointed with the patient.” |

| Understanding PVIs limitations and incapabilities related to their disability “Doctors don’t know how to behave when dealing with a blind person, they don’t know the problem e.g., the doctor shows me the door but it would be better if he walked me to the door.” “[It is important] that the physicians know how to ask how to help (avoiding pushing, pulling, etc.). 1. They should be taught this at university; 2. they should be taught that it is not embarrassing not to know, it is embarrassing not to know how to ask.” “(…) [important is] the form and language of the doctor e.g., [he says] “let’s see” and he shows me results of the tests and I have to remind him that I cannot see.” “Blind people are characterized with greater sensitivity to external stimuli (touch, pain), which is misunderstood and misperceived by medical personnel. There are no procedures to eliminate this misperception.” |

| Architectural Adaptation of the Clinic Space and Surrounding | Equipment and Technologies |

|---|---|

|

|

| Help with Orientation and Spatial Navigation e.g., showing the way to the office, from the couch to the chair, walking to the office, walking to the door, helping to go out of the building. |

| Help with Queuing “At the clinic, I get a number but I can’t see it, someone has to tell me who I’m after, what my number is—so that there is a person who would help.” “Being informed by a lady at the reception desk that I can now enter the surgery.” |

| Support with Documents Support in reading and completing medical records. “Support with paperwork, arranging, gathering, signing, etc.” “Handling documents directly into my hand.” |

| Assisting with any Activities Required for the Examination Assistance from both clinic staff and an assistant of PwDs “It is important there be someone in the clinic who knows about my disability and takes care of me there because, for example, in the office the physician only says: “Please sit down and I don’t know where.” “Before the visit it is important to introduce in Poland a free assistant of a person with disability who would take me to the clinic, direct me and drive me home.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Binder-Olibrowska, K.W.; Godycki-Ćwirko, M.; Wrzesińska, M.A. “To Be Treated as a Person and Not as a Disease Entity”—Expectations of People with Visual Impairments towards Primary Healthcare: Results of the Mixed-Method Survey in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013519

Binder-Olibrowska KW, Godycki-Ćwirko M, Wrzesińska MA. “To Be Treated as a Person and Not as a Disease Entity”—Expectations of People with Visual Impairments towards Primary Healthcare: Results of the Mixed-Method Survey in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013519

Chicago/Turabian StyleBinder-Olibrowska, Katarzyna Weronika, Maciek Godycki-Ćwirko, and Magdalena Agnieszka Wrzesińska. 2022. "“To Be Treated as a Person and Not as a Disease Entity”—Expectations of People with Visual Impairments towards Primary Healthcare: Results of the Mixed-Method Survey in Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013519

APA StyleBinder-Olibrowska, K. W., Godycki-Ćwirko, M., & Wrzesińska, M. A. (2022). “To Be Treated as a Person and Not as a Disease Entity”—Expectations of People with Visual Impairments towards Primary Healthcare: Results of the Mixed-Method Survey in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013519