Research on the Impact of Pro-Environment Game and Guilt on Environmentally Sustainable Behaviour

Abstract

1. Introduction

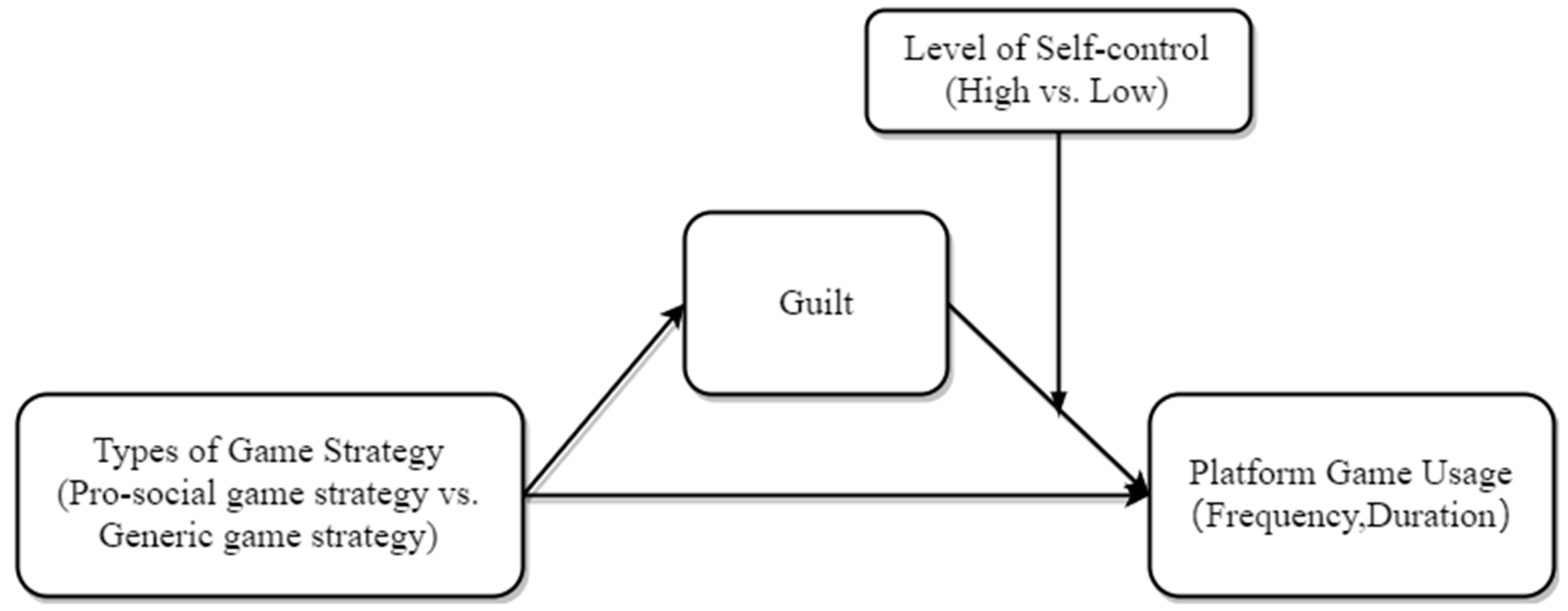

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Game

2.2. Game Strategy

2.3. Social Responsibility, Guilt, and Ethical License

2.4. Self-Control

3. Method and Results

3.1. Study 1

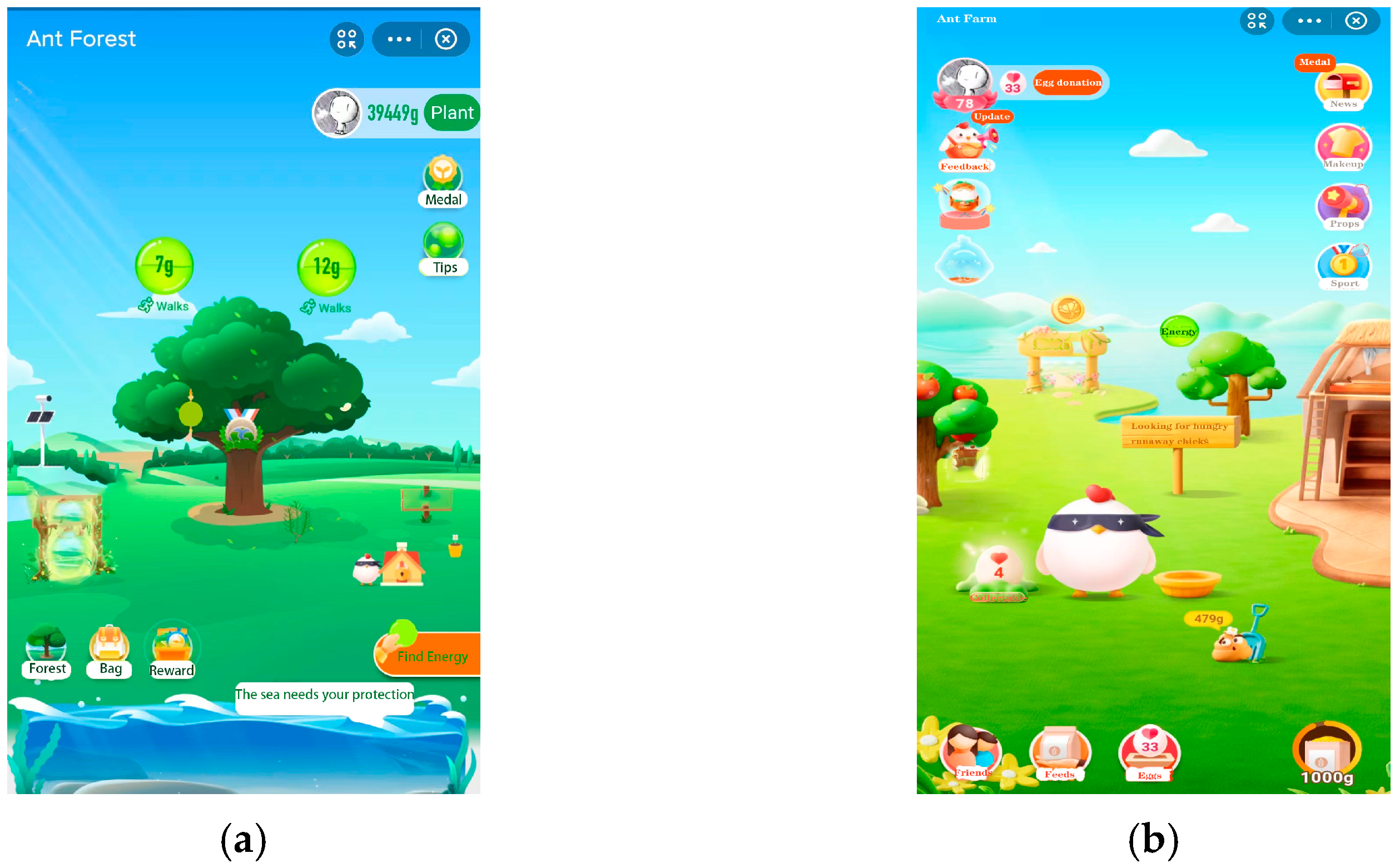

3.1.1. Materials

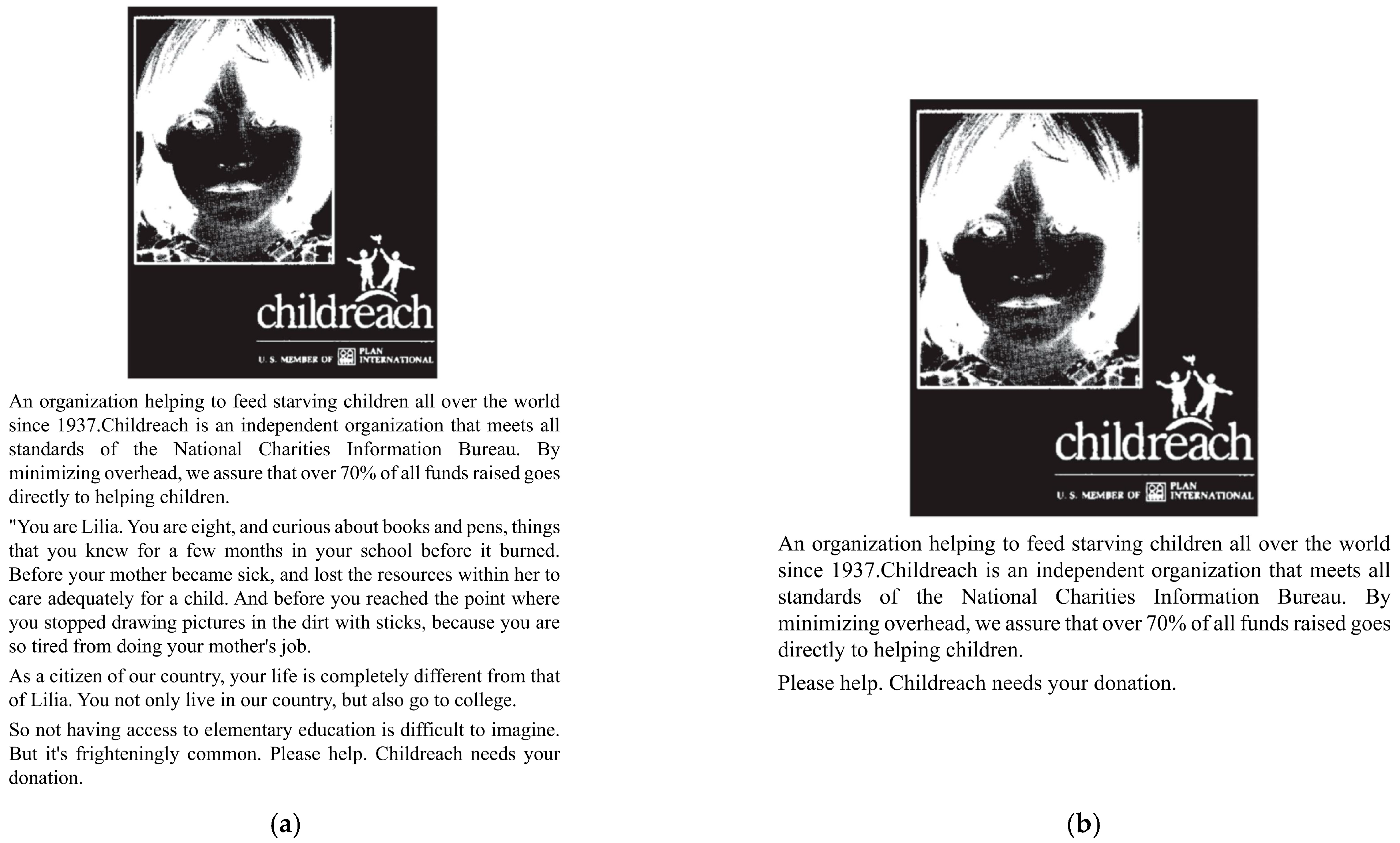

3.1.2. Procedures

3.1.3. Results

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Procedures

3.2.2. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mulcahy, R.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Iacobucci, D. Designing Gamified Apps for Sustainable Consumption: A Field Study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, J. New WeChat “Airplane War” Game Sending Addicted Players to Hospital. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/china-insider/article/1297108/new-wechat-airplane-game-sends-players-hospital (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Feng, W.; Tu, R.; Hsieh, P. Can Gamification Increases Consumers’ Engagement in Fitness Apps? The Moderating Role of Commensurability of the Game Elements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, Y.; Qian, M.; Guo, X.; Chen, R.; Xu, D.; Chen, Y. The Contribution of Fintech to Sustainable Development in the Digital Age: Ant Forest and Land Restoration in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Ministry of Environmental Protection. Research Report on Public Low-Carbon Lifestyle under the Background of Internet Platform Released by the Center for Political Research. Available online: http://www.prcee.org/yjcg/yjbg/201909/t20190909_733041.html (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- World Economic Forum. This App Plants Trees when People Make Lower-Carbon Choices; EcoWatch: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ali, F.; Waheed, A.; Nawaz, S. You Plant a Virtual Tree, We’ll Plant a Real Tree: Understanding Users’ Adoption of the Ant Forest Mobile Gaming Application from a Behavioral Reasoning Theory Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J. Why Do People Use Gamification Services? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammedi, W.; Leclercq, T.; Poncin, I.; Alkire, L. Uncovering the Dark Side of Gamification at Work: Impacts on Engagement and Well-Being. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Renwick, R.; Turner, N.E.; Kirsh, B. Understanding the Lives of Problem Gamers: The Meaning, Purpose, and Influences of Video Gaming. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaby, T.M. Beyond Play: A New Approach to Games. Games Cult. 2007, 2, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M. The ICD-11 Beta Draft Is Available Online. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 375–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Binnewies, C. “Achievement Unlocked!”—The Impact of Digital Achievements as a Gamification Element on Motivation and Performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Asaad, Y.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining the Impact of Gamification on Intention of Engagement and Brand Attitude in the Marketing Context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruano, M.; Frias-Jamilena, D.; Polo-Pena, A.; Peco-Torres, F. The Use of Gamification in Environmental Interpretation and Its Effect on Customer-Based Destination Brand Equity: The Moderating Role of Psychological Distance. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, R.; McAndrew, R.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Iacobucci, D. “Game on!” Pushing Consumer Buttons to Change Sustainable Behavior: A Gamification Field Study. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2593–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roy, R.; Zaman, B. Unravelling the Ambivalent Motivational Power of Gamification: A Basic Psychological Needs Perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 127, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemyss, D.; Cellina, F.; Lobsiger-Kägi, E.; de Luca, V.; Castri, R. Does It Last? Long-Term Impacts of an App-Based Behavior Change Intervention on Household Electricity Savings in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 47, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Kong, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Switching to Green Lifestyles: Behavior Change of Ant Forest Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Gu, M. Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviour through Social Media: An Empirical Study Based on Ant Forest. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Rigby, C.S.; Przybylski, A. The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Mugge, D. Video Games Do Affect Social Outcomes A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Violent and Prosocial Video Game Play. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.; Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.; Rowan, D.; Kubiak, M.A. An Attribution Model of Public Discrimination towards Persons with Mental Illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-Regulation Failure: An Overview. Psychol. Inq. 1996, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Qahri-Saremi, H. Problematic Use of Social Networking Sites: Antecedents and Consequence from a Dual-System Theory Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 1087–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. A Social Skill Account of Problematic Internet Use. J. Commun. 2005, 55, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J.; Hamari, J. The Rise of Motivational Information Systems: A Review of Gamification Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining “Gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Ranney, M.; Hartig, T.; Bowler, P.A. Ecological Behavior, Environmental Attitude, and Feelings of Responsibility for the Environment. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Shimoda, T.A. Responsibility as a Predictor of Ecological Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. ISBN 978-0-12-015210-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Theories of Motivation from an Attributional Perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.J.; Stegge, H. Chapter 2—Measuring Guilt in Children: A Rose by Any Other Name Still Has Thorns. In Guilt and Children; Bybee, J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 19–74. ISBN 978-0-12-148610-5. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F. The Self; Handbook of Social Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eyal, N. Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products; Penguin: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 0-698-19066-1. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.; Yaya, L.; Manolis, C. The Invisible Addiction: Cell-Phone Activities and Addiction among Male and Female College Students. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.; Mullen, E.; Murnighan, J.K. Striving for the Moral Self: The Effects of Recalling Past Moral Actions on Future Moral Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, E.; Monin, B. Consistency Versus Licensing Effects of Past Moral Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsson, P.; Myrseth, K.O.R.; Wollbrant, C. Reconciling Pro-Social vs. Selfish Behavior: On the Role of Self-Control. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2012, 7, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Basil, D.Z.; Ridgway, N.M.; Basil, M.D. Guilt Appeals: The Mediating Effect of Responsibility. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. Applying Cognitive Evaluation Theory to Analyze the Impact of Gamification Mechanics on User Engagement in Resource Recycling. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Ghosh, T.; Dwivedi, Y. Moving beyond the Content: The Role of Contextual Cues in the Effectiveness of Gamification of Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wise, K. How Playable Ads Influence Consumer Attitude: Exploring the Mediation Effects of Perceived Control and Freedom Threat. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoue, E.; Ju, Q.; Hallifax, S.; Serna, A. Analyzing the Relationships between Learners’ Motivation and Observable Engaged Behaviors in a Gamified Learning Environment. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2021, 154, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, D.; Bisschops, I.; Knoop, L.; Tulu, L.; Kujawa-Roeleveld, K.; Masresha, N.; Houtkamp, J. Game over or Play Again? Deploying Games for Promoting Water Recycling and Hygienic Practices at Schools in Ethiopia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 111, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, X. Fueling Pro-Environmental Behaviors with Gamification Design: Identifying Key Elements in Ant Forest with the Kano Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong-Tawiah, D.; Webster, J.; Staples, S.; Cameron, A.; de Guinea, A.; Hung, T. Developing a Gamified Mobile Application to Encourage Sustainable Energy Use in the Office. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias-Jamilena, D.; Fernandez-Ruano, M.; Polo-Pena, A. Gamified Environmental Interpretation as a Strategy for Improving Tourist Behavior in Support of Sustainable Tourism: The Moderating Role of Psychological Distance. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, M.; Brauer, M.; Kuntz, K.; Shukla, R.; Bensch, I. Making Cool Choices for Sustainability: Testing the Effectiveness of a Game-Based Approach to Promoting pro-Environmental Behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, C.; Cheong, F.; Filippou, J. Quick Quiz: A Gamified Approach for Enhancing Learning. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2013 Proceedings, Jeju Island, Korea, 18–22 June 2013; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, N.; Huang, Y.-T. Why Do People Play Games on Mobile Commerce Platforms? An Empirical Study on the Influence of Gamification on Purchase Intention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 106991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item |

|---|---|

| guilt |

|

| |

| Self-control |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Game withdrawal |

|

|

| The Guilt of Normal Games | The Guilt of Environmental Play | Self-Control |

|---|---|---|

| 0.837 | 0.862 | 0.885 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Zhang, G.; Hu, Q. Research on the Impact of Pro-Environment Game and Guilt on Environmentally Sustainable Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013406

Chen J, Zhang G, Hu Q. Research on the Impact of Pro-Environment Game and Guilt on Environmentally Sustainable Behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20):13406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013406

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiaxing, Guangling Zhang, and Qinfang Hu. 2022. "Research on the Impact of Pro-Environment Game and Guilt on Environmentally Sustainable Behaviour" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 20: 13406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013406

APA StyleChen, J., Zhang, G., & Hu, Q. (2022). Research on the Impact of Pro-Environment Game and Guilt on Environmentally Sustainable Behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13406. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013406