A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in Spain in the COVID-19 Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Screening

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Assessment of Bias Risk

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Screening

3.2. Study Characteristics

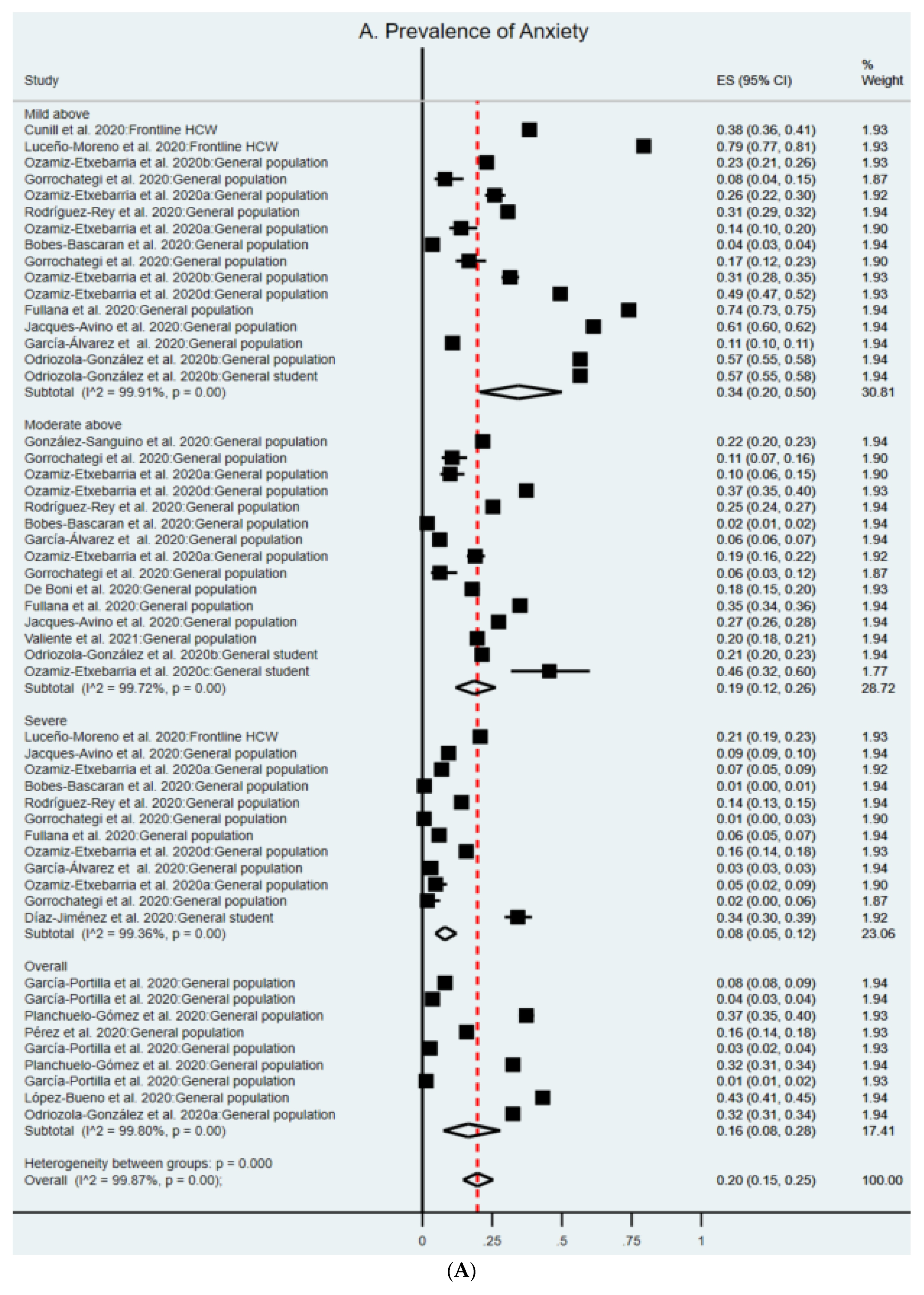

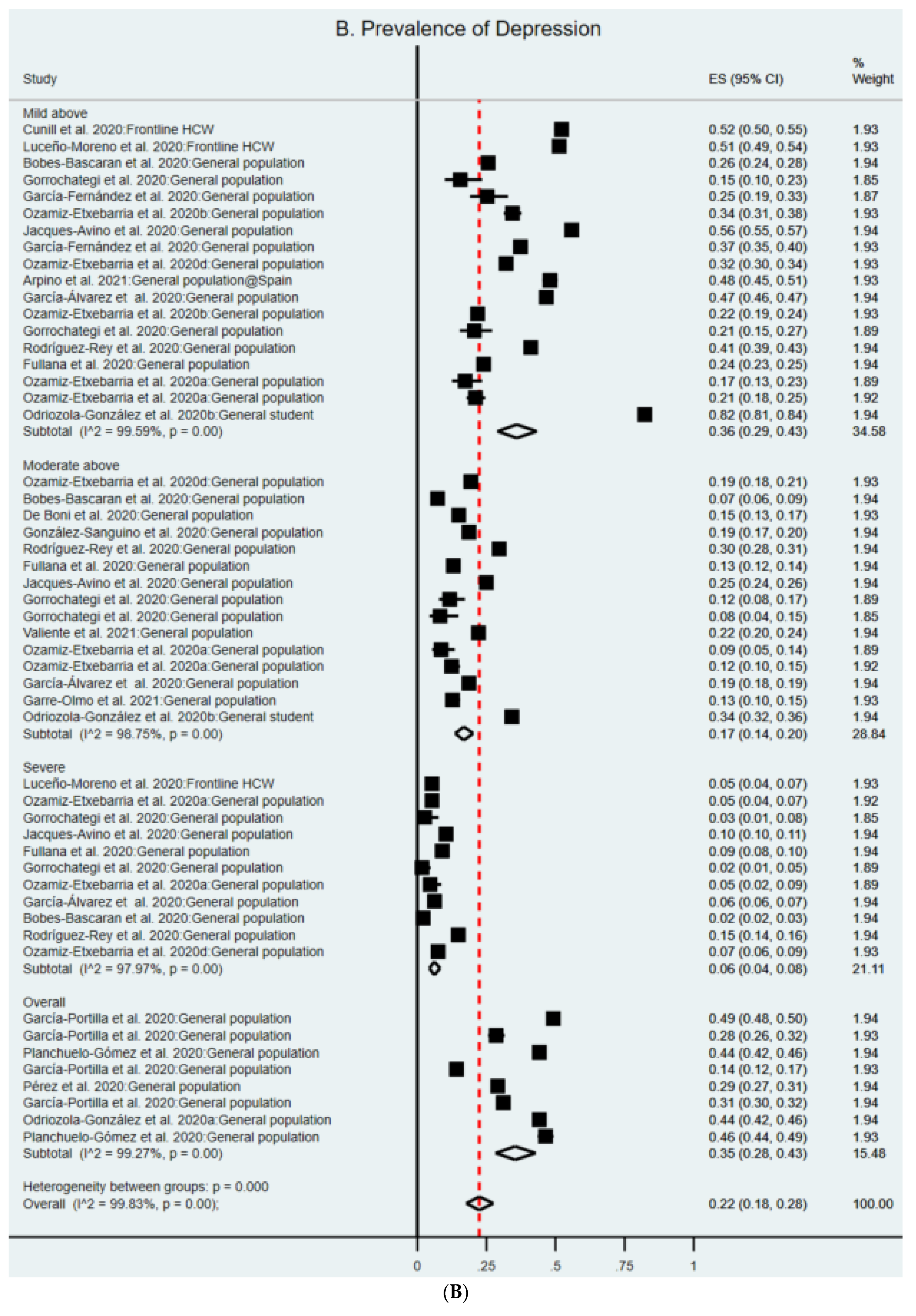

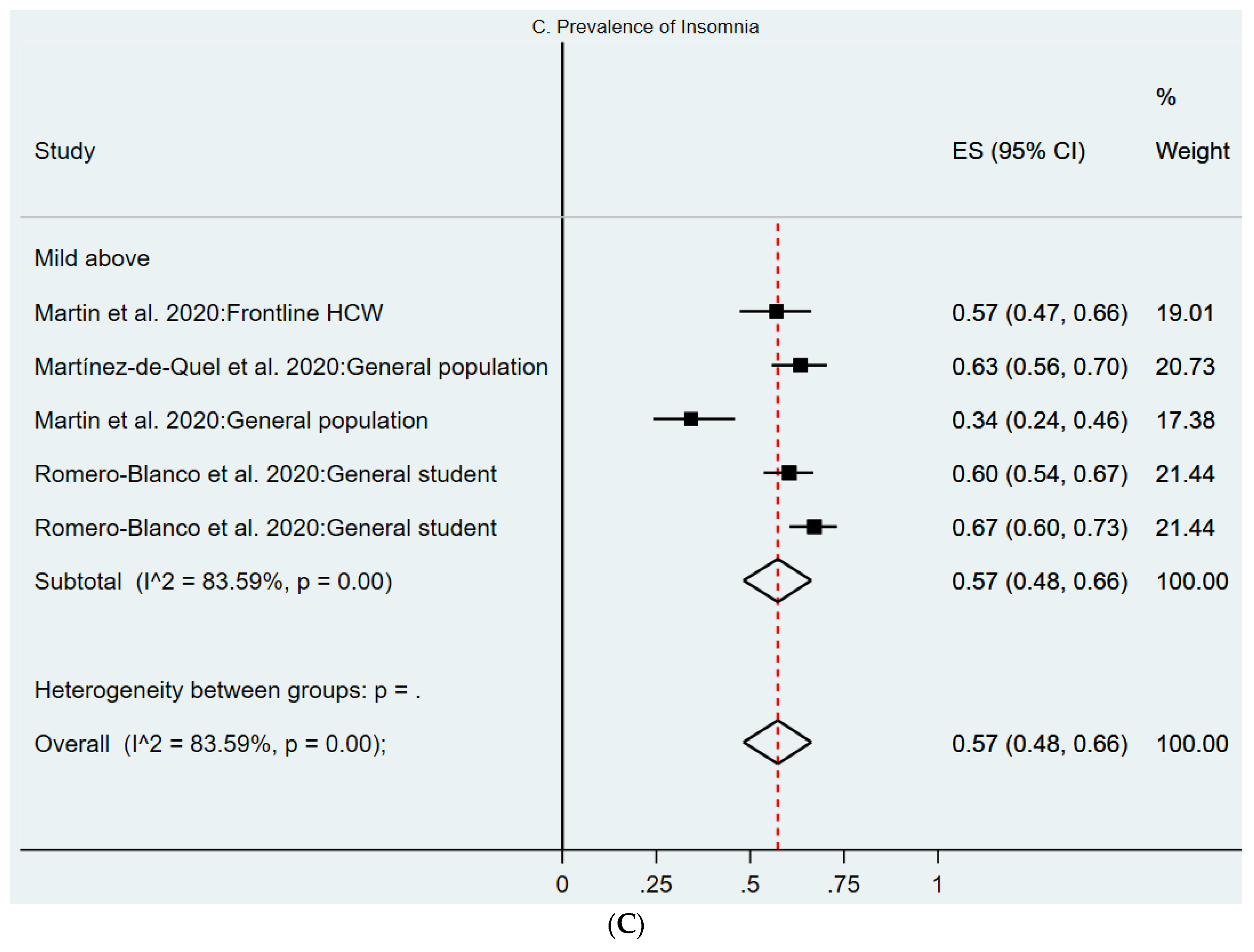

3.3. Pooled Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia

3.4. Quality of Articles

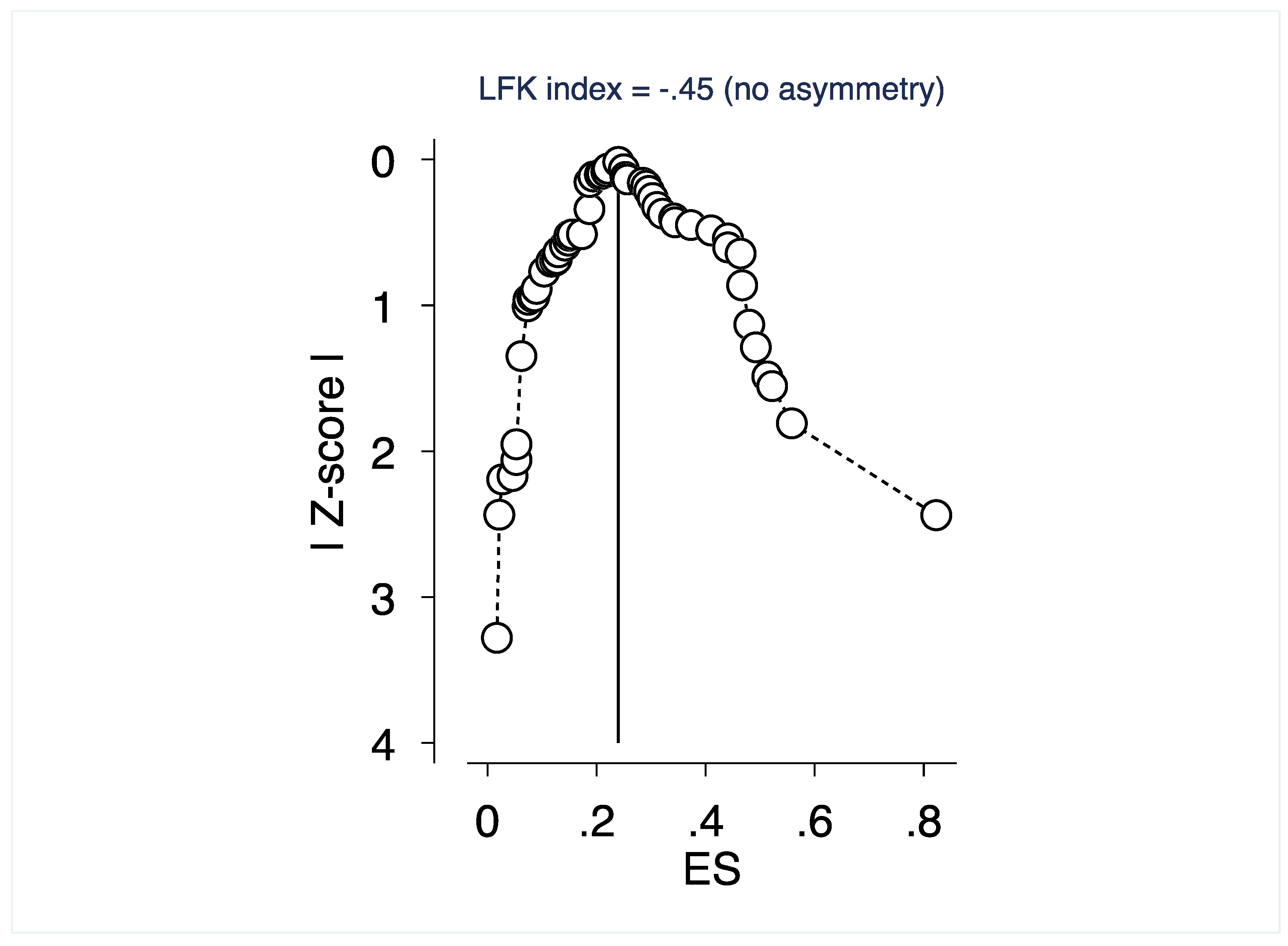

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Findings

4.2. Comparison with Prior Meta-Analyses

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliver, N.; Barber, X.; Roomp, K.; Roomp, K. Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Large-Scale, Online, Self-Reported Population Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 9, e21319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, C.; Autenrieth, L.K.; Asselmann, E.; Pané-Farré, C.A. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: Associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picaza Gorrochategi, M.; Eiguren Munitis, A.; Dosil Santamaria, M.; Ozamiz Etxebarria, N. Stress, anxiety, and depression in people aged over 60 in the COVID-19 outbreak in a sample collected in Northern Spain. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavra-Velasco, B.; García-Albuerne, Y.; Martín-García, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Farah, N.; Dong, R.K.; Chen, R.Z.; Xu, W.; Yin, A.; Chen, B.Z.; Delios, A.; Miller, S.; Wan, X.; et al. The Mental Health Under the COVID-19 Crisis in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Chen, J.; Barnet, J.; Zhang, A.; Dong, R.K.; Xu, W.; Yin, A.; Chen, B.Z.; Delios, A.; Chen, R.Z.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Mental Health Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Southeast Asia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Miller, S.O.; Xu, W.; Yin, A.; Chen, B.Z.; Delios, A.; Dong, R.K.; Chen, R.Z.; McIntyre, R.S.; Wan, X.; et al. Meta-Analytic Evidence of Depression and Anxiety in Eastern Europe during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Yang, B.X.; Luo, D.; Liu, Q.; Ma, S.; Huang, R.; Lu, W.; Majeed, A.; Lee, Y.; Lui, L.M.W.; et al. The Mental Health Effects of COVID-19 on Health Care Providers in China. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 117, 635–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, R.Z.; Dong, R.K.; Dong, Z.; Ye, Y.; Tong, L.; Chen, B.Z.; Zhao, R.; et al. One Year of Evidence on Mental Health in China in the COVID-19 Crisis—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medrxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunter, J.P.; Saratzis, A.; Sutton, A.J.; Boucher, R.H.; Sayers, R.D.; Bowne, M.J. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Xu, C.; Lin, L.; Doan, T.; Chud, H.; Thalib, L.; Doi, S.A.R. P value—driven methods were underpowered to detect publication bias: Analysis of Cochrane review meta-analyses. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 118, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Barendregt, J.J.; Doi, S. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2018, 16, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullana, M.A.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Vieta, E.; Radua, J. Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M.; Bordone, V.; Solé-Auró, A. Older People’s Nonphysical Contacts and Depression During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Gerontologist 2020, 61, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobes-Bascarán, T.; Sáiz, P.A.; Velasco, A.; Martínez-Cao, C.; Psych, C.P.; Portilla, A.; de la Fuente-Tomas, L.; García-Alvarez, L.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. Early Psychological Correlates Associated With COVID-19 in A Spanish Older Adult Sample. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, R.B.D.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Correa, J.; Cardoso, T.D.A.; Ballester, P.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Bastos, F.I.; Kapczinski, F. Depression, Anxiety, and Lifestyle Among Essential Workers: A Web Survey From Brazil and Spain During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Jiménez, R.M.; Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Martín-Cano, M.C.; Fuente-Robles, Y.M.D.L. Anxiety levels among social work students during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Soc. Work Health Care 2020, 59, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Fuente-Tomás, L.d.l.; García-Portilla, M.P. Early psychological impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in a large Spanish sample. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; López-Roldán, P.D.; Padilla, S.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. Mental Health in Elderly Spanish People in Times of COVID-19 Outbreak. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Portilla, P.; Tomás, L.d.l.F.; Bobes-Bascarán, T.; Treviño, L.J.; Madera, P.Z.; Álvarez, M.S.; Miranda, I.M.; Álvarez, L.G.; Martínez, P.A.S.; Bobes, J. Are older adults also at higher psychological risk from COVID-19? Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre-Olmo, J.; Turró-Garriga, O.; Martí-Lluch, R.; Zacarías-Pons, L.; Alves-Cabratosa, L.; Serrano-Sarbosa, D.; Vilalta-Franch, J.; Ramos, R. Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: A cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 104, 152214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos, M.Á.; Saiz, J.; López-Gómez, A.; Ugidos, C.; Muñoz, M. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosil, M.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Redondo, I.; Picaza, M.; Jaureguizar, J. Psychological Symptoms in Health Professionals in Spain After the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 606121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques-Aviñódoi, C.; López-Jiménez, T.; Medina-Perucha, L.; de Bont, J.; Gonçalves, A.Q.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Berenguera, A. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. BMJ 2020, 10, e044617. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bueno, R.; Calatayud, J.; Ezzatvar, Y.; Casajús, J.A.; Smith, L.; Andersen, L.L.; López-Sánchez, G.F. Association Between Current Physical Activity and Current Perceived Anxiety and Mood in the Initial Phase of COVID-19 Confinement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.H.S.; Serrano, J.P.; Cambriles, T.D.; Arias, E.M.A.; Méndez, J.; del Yerro Álvarez, M.J.; Sánchez, M.G. Sleep characteristics in health workers exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-de-Quela, Ó.; Suárez-Iglesias, D.; López-Floresc, M.; Pérez, C.A. Physical activity, dietary habits and sleep quality before and during COVID-19 lockdown: A longitudinal study. Appetite 2021, 158, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; Padilla, S.; López-Roldán, P.D. Gender difference in emotional response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mònica, C.O.; Maria, A.A.; Bernat-Carles, S.F.; Josefina, P.M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Spanish Health Professionals: A Description of Physical and Psychological Effects. DUGiDocs Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2020, 22, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M.J.; Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 290, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia-Muñiz, M.J.; Luis-García, R.d. Psychological symptoms of the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis and confinement in the population of Spain. J. Health Psychol. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Picaza-Gorrochategui, M.; Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. SciELO 2020, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Mondragon, N.I.; Santamaría, M.D.; Gorrotxategi, M.P. Psychological Symptoms During the Two Stages of Lockdown in Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Investigation in a Sample of Citizens in Northern Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Santamaría, M.D.; Munitis, A.E.; Gorrotxategi, M.P. Reduction of COVID-19 Anxiety Levels Through Relaxation Techniques: A Study Carried Out in Northern Spain on a Sample of Young University Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Santxo, N.B.; Mondragon, N.I.; Santamaría, M.D. The Psychological State of Teachers During the COVID-19 Crisis: The Challenge of Returning to Face-to-Face Teaching. Front. Psychol. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Masegoso, A.; Hernández-Espeso, N. Levels and variables associated with psychological distress during confinement due to the coronavirus pandemic in a community sample of Spanish adults. Wiley 2020, 28, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Odriozola-González, P.; Irurtia, M.J.; Luis-García, R. Longitudinal evaluation of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Collado, S. Psychological Impact and Associated Factors During the Initial Stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Among the General Population in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Blanco, C.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Prado-Laguna, M.d.C.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Sleep Pattern Changes in Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiente, C.; Contreras, A.; Peinado, V.; Trucharte, A.; Martínez, A.P.; Vázquezdoi, C. Psychological Adjustment in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Positive and Negative Mental Health Outcomes in the General Population. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Batra, K.; Liu, T.; Dong, R.K.; Xu, W.; Yin, A.; Delios, A.Y.; Chen, B.Z.; Chen, R.Z.; Miller, S.; et al. Meta-Analytical Evidence on Mental Disorder Symptoms During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Latin America. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 12, 2001192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; APollak, T.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénata, J.M.; Blais-Rochettea, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.-E.; Dalexisc, R.D.; Goulet, M.-A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablo, G.S.; Serrano, J.V.; Catalan, A.; Arango, C.; Moreno, C.; Ferre, F.; Shin, J.I.; Sullivan, S.; Brondino, N.; Solmi, M. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Nagarajan, R.; Sayaa, G.K.; Menon, V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Silver, Z.; Wonga, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Drakos, A.; Zuo, Q.K.; Huang, E. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Jia, X.; Shi, H.; Niu, J.; Yin, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bareeqa, S.B.; Ahmed, S.I.; Samar, S.S.; Yasin, W.; Zehra, S.; Monese, G.M.; Gouthro, R.V. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in china during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 56, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Huang, W.; Pan, H.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Mental Health During the Covid-19 Outbreak in China: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chudzicka-Czupała, A.; Tee, M.L.; Núñez, M.I.L.; Tripp, C.; Fardin, M.A. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrasa, B.; Olaya, B.; Lopez-Anton, R.; Cámara, C.d.l.; Lobo, A.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of anxiety disorder among older adults in Spain: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; BaHammam, A.S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Saif, Z.; Faris, M.; Vitiello, M.V. Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic by population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 17, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheras, I.; Gracia-García, P.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; López-Antón, R.; de la Cámara, C.; Lob, A.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Anxiety in Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.Y.-M.; Yeung, W.-F.; Lam, J.C.-S.; Chun-SumYuen, S.; Lam, S.C.; Chi-HoChung, V.; Chung, K.-F.; Lee, P.H.; Ho, F.Y.-Y.; Ho, J.Y.-S. Prevalence of sleep disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak in an urban Chinese population: A cross-sectional study. Sleep Med. 2020, 74, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.; Purohit, N.; Sultan, A.; Ma, P.; Lisako, E.; McKyer, J.; Ahmed, H.U. Prevalence of mental disorders in South Asia: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Lee, Y. Preventing suicide in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnefeesi, Y.; Siegel, A.; Lui, L.M.W.; Teopiz, K.M.; Ho, R.C.M.; Lee, Y.; Nasri, F.; Gill, H.; Lin, K.; Cao, B.; et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Number of Studies/Samples * | Percent (%) | Level of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 28/38 | 100 | |

| Design | Study | ||

| Cohort | 4 | 14.29 | |

| Cross-sectional | 24 | 85.71 | |

| Publication status | Study | ||

| Preprint | 2 | 7.14 | |

| Published | 26 | 92.86 | |

| Quality | Study | ||

| >6 | 7 | 25.0 | |

| Between 5 and 6 | 21 | 75.0 | |

| <5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Population | Sample | ||

| Frontline HCW | 3 | 7.89 | |

| General population | 30 | 78.95 | |

| Student | 5 | 13.16 | |

| Outcome # | Prevalence | ||

| Anxiety | 52 | 47.1 | |

| Depression | 52 | 47.1 | |

| Insomnia | 5 | 4.59 | |

| Severity # | Prevalence | ||

| Above mild | 39 | 35.78 | |

| Above moderate | 30 | 27.52 | |

| Severe | 23 | 21.1 | |

| Overall | 17 | 15.6 | |

| Median (mean) | Range | ||

| Sample size | 1199 (2272) | 44–21207 | Sample |

| Response rate | 70.3% (73.9%) | 20.0–98.0% | Sample |

| Female portion | 70.25% (64.7%) | 0–100% | Sample |

| First-Level Subgroup | Second-Level Subgroup | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregated prevalence | 22% | 18–26% | |

| Population | Frontline HCW | 42% | 22–64% |

| General population | 19% | 16–23% | |

| Student | 50% | 32–69% | |

| Outcome | Anxiety | 20% | 15–25% |

| Depression | 22% | 18–28% | |

| Insomnia | 57% | 48–66% | |

| Severity | Above mild | 38% | 30–46% |

| Above moderate | 18% | 14–21% | |

| Severe | 7% | 5–9% | |

| Overall | 25% | 16–34% | |

| Quality | Studies with high quality | 21% | 15–27% |

| Studies with medium quality | 23% | 19–27% |

| Groups | Subgroups | Anxiety | Depression | Insomnia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | 22 | 22 | 3 | |

| Number of samples | 29 | 30 | 5 | |

| Total # participants | 82,024 | 82,890 | 745 | |

| Aggregated prevalence | 20%, 95% CI: 15–25% | 22%, 95% CI: 18–28% | 57%, 95% CI: 48–66% | |

| Population | Frontline HCW | 46%, 95% CI: 14–80% | 33%, 95% CI: 06–69% | 57%, 95% CI: 47–66% |

| General population | 17%, 95% CI: 12–22% | 20%, 95% CI: 16–25% | 55%, 95% CI: 48–61% | |

| Student | 39%, 95% CI: 18–62% | 59%, 95% CI: 58–61% | 64%, 95% CI: 59–68% | |

| Severity | Above mild | 34%, 95% CI: 20–50% | 36%, 95% CI: 29–43% | 57%, 95% CI: 48–66% * |

| Above moderate | 19%, 95% CI: 12–26% | 17%, 95% CI: 14–20% | ||

| Severe | 8%, 95% CI: 5–12% | 6%, 95% CI: 4–8% | ||

| Overall | 16%, 95% CI: 5–12% | 35%, 95% CI: 28–43% | ||

| Instrument | DASS-21 | 15%, 95% CI: 11–20% | 21%, 95% CI: 15–28% | |

| GAD-7/PHQ-9 | 31%, 95% CI: 17–46% | 22%, 95% CI: 13–32% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.X.; Chen, R.Z.; Xu, W.; Yin, A.; Dong, R.K.; Chen, B.Z.; Delios, A.Y.; Miller, S.; McIntyre, R.S.; Ye, W.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in Spain in the COVID-19 Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021018

Zhang SX, Chen RZ, Xu W, Yin A, Dong RK, Chen BZ, Delios AY, Miller S, McIntyre RS, Ye W, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in Spain in the COVID-19 Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021018

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Stephen X., Richard Z. Chen, Wen Xu, Allen Yin, Rebecca Kechen Dong, Bryan Z. Chen, Andrew Yilong Delios, Saylor Miller, Roger S. McIntyre, Wenping Ye, and et al. 2022. "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in Spain in the COVID-19 Crisis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021018

APA StyleZhang, S. X., Chen, R. Z., Xu, W., Yin, A., Dong, R. K., Chen, B. Z., Delios, A. Y., Miller, S., McIntyre, R. S., Ye, W., & Wan, X. (2022). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in Spain in the COVID-19 Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021018