Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Energy

3. Environment and Society (Thermal Comfort and IAQ)

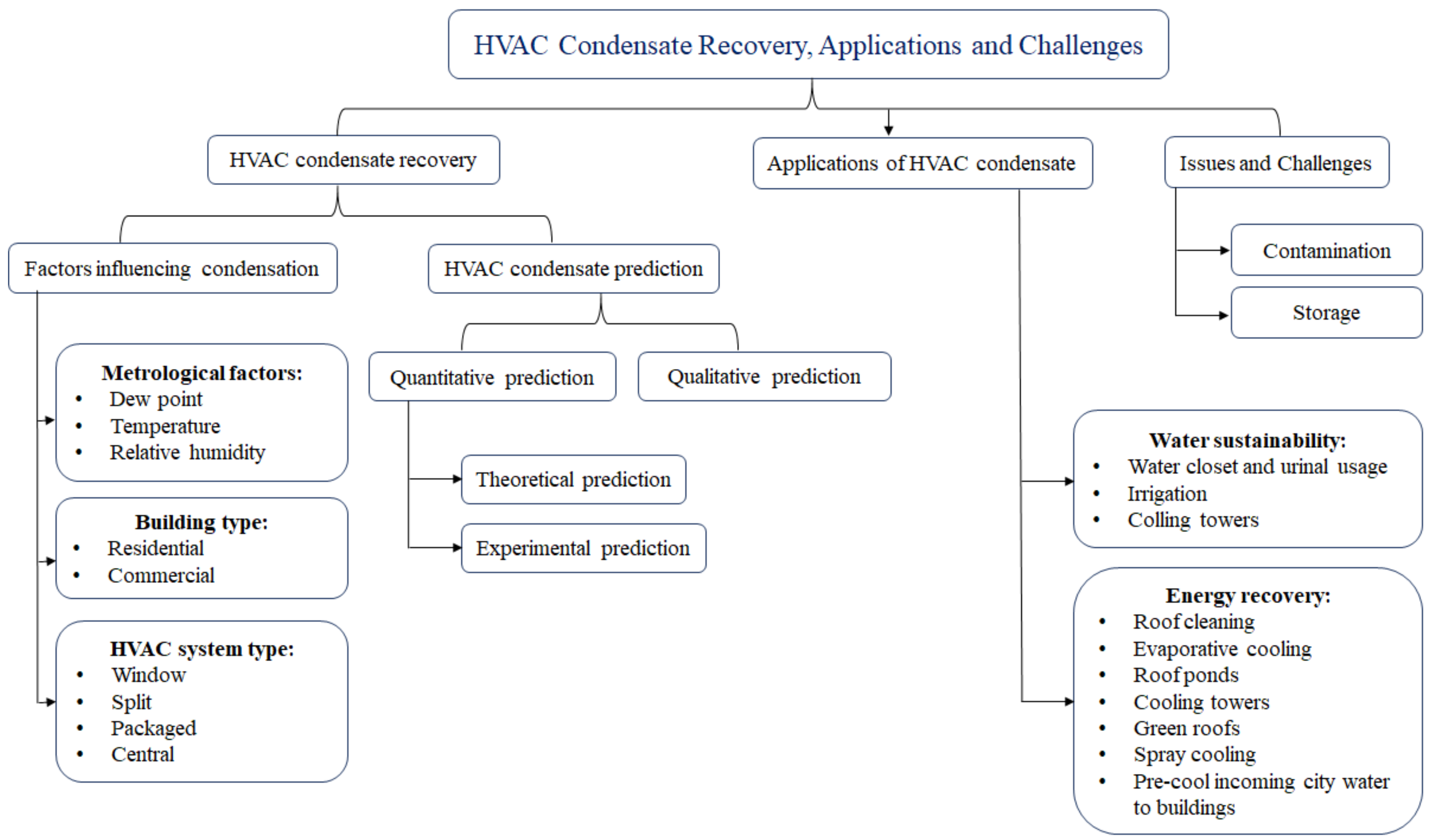

4. Water Recovery

5. Retrofitting of Existing HVAC Systems (Modification of Old HVAC Systems)

- Measurement of HVAC system performance.

- Identification of potential retrofit alternatives, such as smart controlling systems, upgrading mechanical systems, energy and water recovery, and utilization of renewable energy sources.

- Establishment of the relation between the investment of retrofitting and the sustainability performance.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- Improvement and retrofitting of the building design are very effective for improving the performance of HVAC systems.

- All decision-making parameters for the planning of sustainable HVAC systems, such as occupancy, comfort, health, building type, and cost must be extensively studied.

- Important parameters must be considered in using renewable technologies in HVAC systems to achieve sustainability.

- The use of developed and advanced designs and control strategies in the HVAC systems could increase their sustainability remarkably.

- Improving IAQ and occupants’ health by focusing on ventilation systems and microbial contamination prevention in HVAC systems.

- Water and energy recovery in HVAC systems are crucial parameters for improving sustainability.

- The retrofitting of the existing HVAC system is a vital action in the current situation.

- Optimum plans need to take into account all the advantages and disadvantages of various options while considering the available facilities, conditions, risks, and cost.

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Ren, H.; Lin, W. A review of heating, ventilation and air conditioning technologies and innovations used in solar-powered net zero energy Solar Decathlon houses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishna, I.V.; Manickam, V. Chapter Two—Sustainable Development. In Environmental Management; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

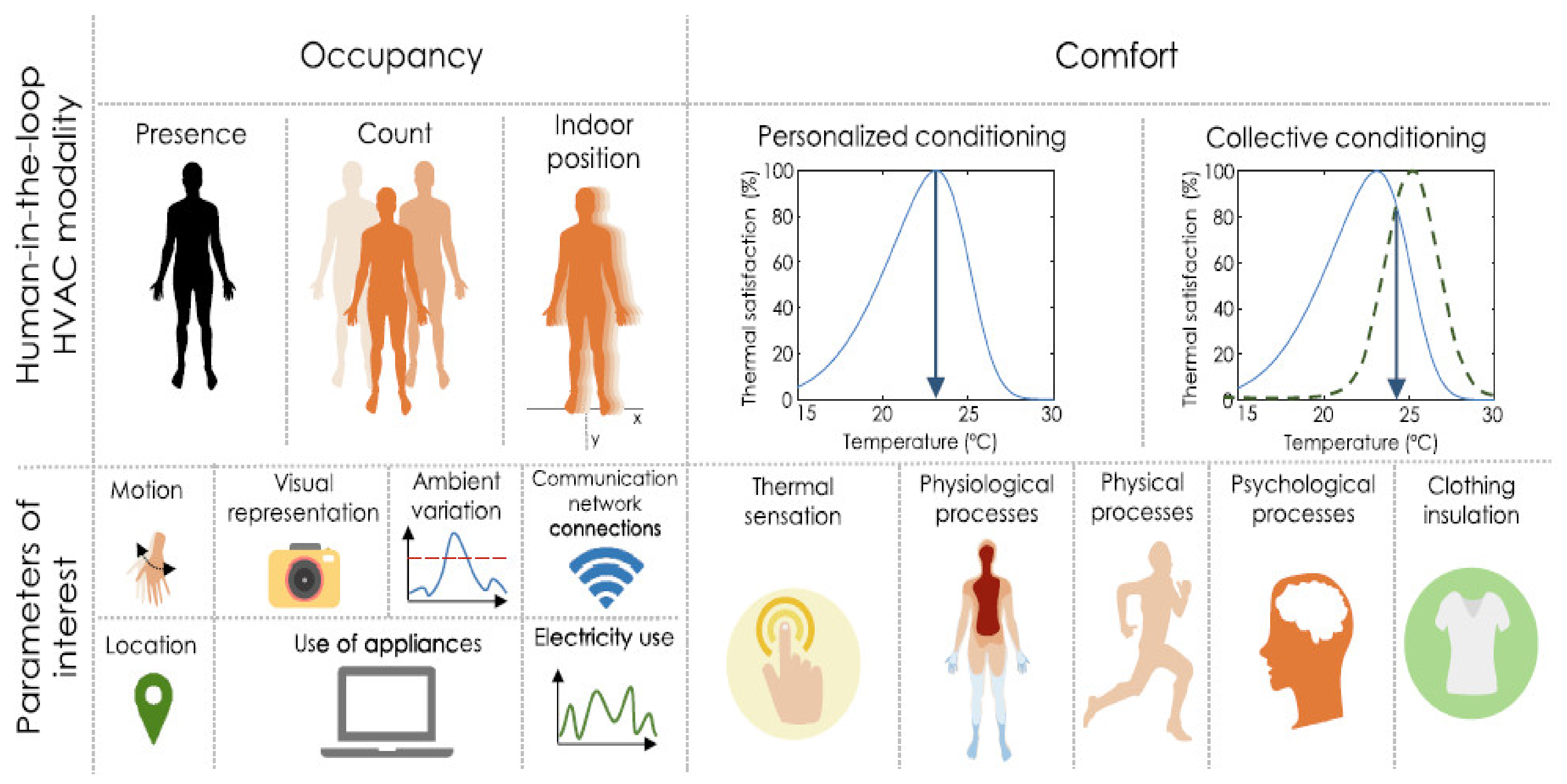

- Jung, W.; Jazizadeh, F. Human-in-the-loop HVAC operations: A quantitative review on occupancy, comfort, and energy-efficiency dimensions. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1471–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchaei, A.G.; Hosseini, M.; Akbari, H. Energy savings potentials of commercial buildings by urban heat island reduction strategies in Montreal (Canada). Energy Build. 2016, 110, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

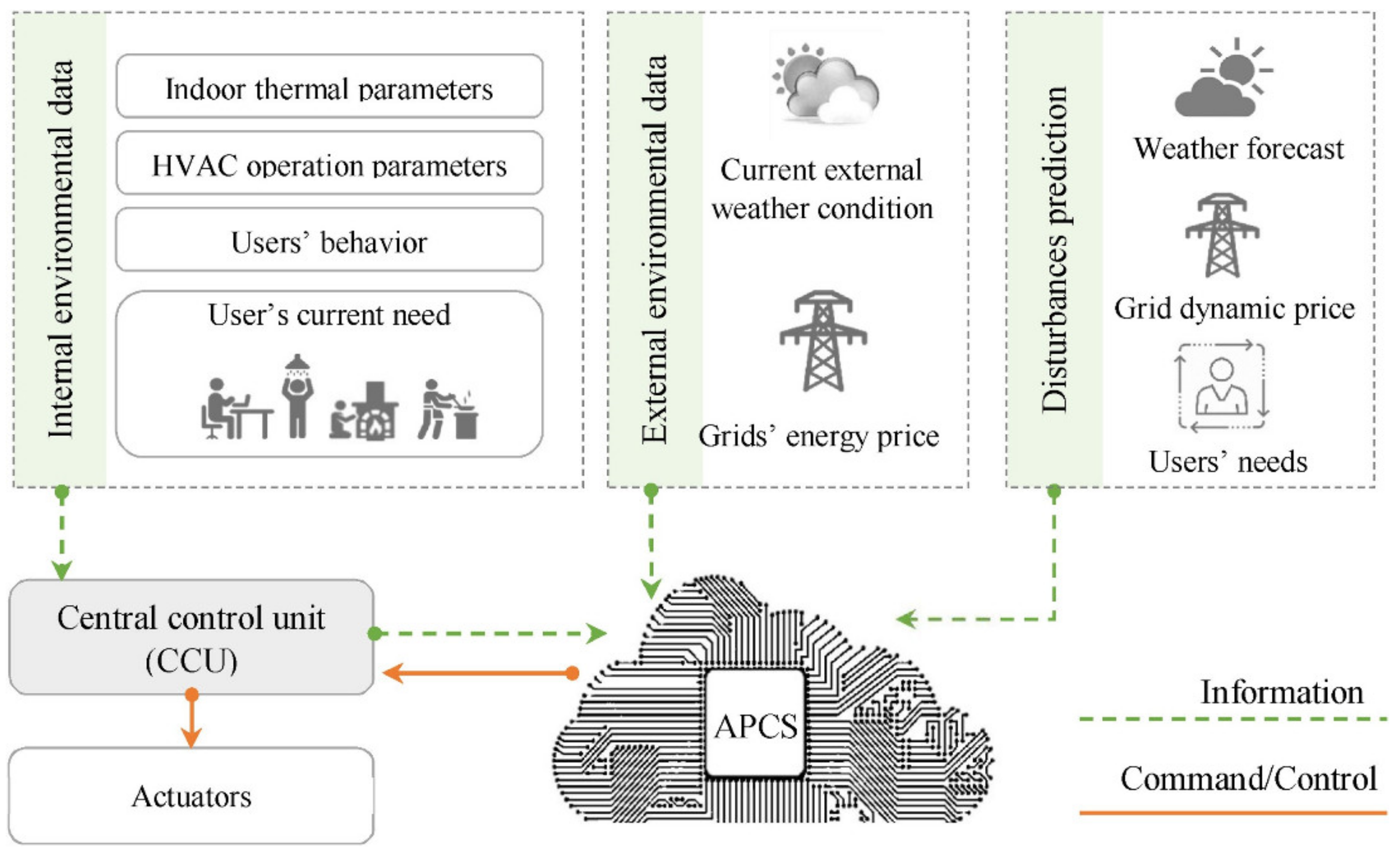

- Gholamzadehmir, M.; Del Pero, C.; Buffa, S.; Fedrizzi, R.; Aste, N. Adaptive-predictive control strategy for HVAC systems in smart buildings—A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfouli, M.M.S.; Moghimi, S.; Azizpour, F.; Mat, S.; Sopian, K. Feasibility of saving energy by using VSD in HVAC system, a case study of large scale hospital in Malaysia. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2014, 10, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Huang, G.; Wang, Y. HVAC system design under peak load prediction uncertainty using multiple-criterion decision making technique. Energy Build. 2015, 91, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ma, Z.; Wang, F. A multi-objective design optimization strategy for vertical ground heat exchangers. Energy Build. 2015, 87, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R. A review of HVAC systems requirements in building energy regulations. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, N.; Amin, M.H.; Alghoul, M.; Badiei, M.; Mohammad, M.; Gasaymeh, S.S.; Amin, N.; Sopian, K. Key factors of desiccant-based cooling systems: Materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 159, 113946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.M.; Rehman, S. Renewable and Sustainable Air Conditioning. In Sustainable Air Conditioning Systems; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Enteria, N.; Awbi, H.; Yoshino, H. Advancement of the Desiccant Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning (DHVAC) Systems. In Desiccant Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pottathara, Y.B.; Tiyyagura, H.R.; Ahmad, Z.; Sadasivuni, K.K. Graphene Based Aerogels: Fundamentals and Applications as Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2020, 30, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdadi, Z.; Maleki, A.; Azizi, M.; Asim, N. Evaporative Passive Cooling Designs for Buildings. Strat. Plan. Energy Environ. 2019, 38, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdadi, Z.; Maleki, A.; Mohammad, M.; Asim, N.; Azizi, M. Coupled Evaporative and Desiccant Cooling Systems for Tropical Climate. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 2, 262–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. Solar Heating and Cooling Systems: Fundamentals, Experiments and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Xu, Z.; Ge, T. Introduction to solar heating and cooling systems. In Advances in Solar Heating and Cooling; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2016; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Kashkooli, F.M.; Dehghani-Sanij, A.; Kazemi, A.; Bordbar, N.; Farshchi, M.; Elmi, M.; Gharali, K.; Dusseault, M.B. A comprehensive study of geothermal heating and cooling systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 44, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, M.; Malmquist, A.; Isalgue, A.; Martin, A. Biomass-fired combined cooling, heating and power for small scale applications—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.X.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, L.W.; Du, S.; Fang, C. Performance Analysis on a Novel Micro-Scale Combined Cooling, Heating and Power (Cchp) System for Domestic Utilization Driven by Biomass Energy. Renew. Energy 2018, 96, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Dincer, I.; Rosen, M. Development and analysis of sustainable energy systems for building HVAC applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 87, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucentini, M.; Naso, V.; Borreca, M. Parametric Performance Analysis of Renewable Energy Sources HVAC Systems for Buildings. Energy Procedia 2014, 45, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nassif, N. Performance analysis of supply and return fans for HVAC systems under different operating strategies of economizer dampers. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kialashaki, Y. Energy and economic analysis of model-based air dampers strategies on a VAV system. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 4687–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavy, M.; Li, T.; Siegel, J.A. Energy use in residential buildings: Analyses of high-efficiency filters and HVAC fans. Energy Build. 2020, 209, 109697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainge, Z. HVAC efficiency: Can filter selection reduce HVAC energy costs? Filtr. Sep. 2007, 44, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, J.A.; Hsu, W.-L.; Paul, S.; Yu, L.; Daiguji, H. A review of solid desiccant dehumidifiers: Current status and near-term development goals in the context of net zero energy buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.; Chou, S.; Islam, M. Integrating Composite Desiccant and Membrane Dehumidifier to Enhance Building Energy Efficiency. Energy Procedia 2017, 143, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Cai, W.J.; Soh, Y.C.; Li, S.J.; Lu, L.; Xie, L. A simplified modeling of cooling coils for control and optimization of HVAC systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 2915–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Ersöz, M.A. The effect of wind speed on the economical optimum insulation thickness for HVAC duct applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukarno, R.; Putra, N.; Hakim, I.I.; Rachman, F.F.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Utilizing heat pipe heat exchanger to reduce the energy consumption of airborne infection isolation hospital room HVAC system. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, A.; Yağlı, H.; Bilgic, H.H.; Koç, Y.; Özdemir, A. Performance analysis of a novel organic fluid filled regenerative heat exchanger used heat recovery ventilation (OHeX-HRV) system. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 41, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eades, W.G. Energy and water recovery using air-handling unit condensate from laboratory HVAC systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldanlou, A.S.; Kalbasi, R.; Afrand, M. Energy usage reduction in an air handling unit by incorporating two heat recovery units. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Kalbasi, R.; Afrand, M. Solutions for enhancement of energy and exergy efficiencies in air handling units. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Baky, M.A.A. Heat pipe heat exchanger for heat recovery in air conditioning. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2007, 27, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardiana-Idayu, A.; Riffat, S. Review on heat recovery technologies for building applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.; Winarta, S.M.A. Experimental Study of Heat Pipe Heat Exchanger Multi Fin for Energy Efficiency Effort in Operating Room Air System. Int. J. Technol. 2018, 9, 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadzadehtalatapeh, M.; Yau, Y. The application of heat pipe heat exchangers to improve the air quality and reduce the energy consumption of the air conditioning system in a hospital ward—A full year model simulation. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2344–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, P.M.; Riffat, S. A comprehensive review of heat recovery systems for building applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, B.; Sofia, E.; Putra, N. Experimental analysis of a multistage direct-indirect evaporative cooler using a straight heat pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 171, 115133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumah, A.S.; Hakim, I.I.; Sukarno, R.; Rachman, F.F.; Putra, N. The Application of U-shape Heat Pipe Heat Exchanger to Reduce Relative Humidity for Energy Conservation in Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) Systems. Int. J. Technol. 2019, 10, 291–319. [Google Scholar]

- Martı́nez, F.J.R.; Plasencia, M.A.Á.-G.; Gómez, E.V.; Dı́ez, F.V.; Martı́n, R.H. Design and experimental study of a mixed energy recovery system, heat pipes and indirect evaporative equipment for air conditioning. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, M.R.; Fauchoux, M.; Ge, G.; Besant, R.W.; Simonson, C.J. Expected energy and economic benefits, and environmental impacts for liquid-to-air membrane energy exchangers (LAMEEs) in HVAC systems: A review. Appl. Energy 2014, 127, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, M.R.; Besant, R.W.; Simonson, C.J. Performance Testing of 2-Fluid and 3-Fluid Liquid-to-Air Membrane Energy Exchangers for Hvac Applications in Cold–Dry Climates. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer. 2016, 106, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruneru, S.T.W.; Vafai, K.; Sauret, E.; Gu, Y. Application of porous metal foam heat exchangers and the implications of particulate fouling for energy-intensive industries. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 228, 115968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Ullah, N.; Ahmad, J.; Sikandar, F.; Ehsan, M.M.; Salehin, S.; Bhuiyan, A.A. Heat transfer and pressure drop performance of Nanofluid: A state-of- the-art review. Int. J. Thermofluids 2021, 9, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Darkwa, J.; Kokogiannakis, G. Review of phase change emulsions (PCMEs) and their applications in HVAC systems. Energy Build. 2015, 94, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abu-Hamdeh, N.H.; Melaibari, A.A.; Alquthami, T.S.; Khoshaim, A.; Oztop, H.F.; Karimipour, A. Efficacy of incorporating PCM into the building envelope on the energy saving and AHU power usage in winter. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 43, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of double-layer PCM radiant floor system containing two types of inorganic composite PCMs. Energy Build. 2020, 211, 109806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nariman, A.; Kalbasi, R.; Rostami, S. Sensitivity of AHU power consumption to PCM implementation in the wall-considering the solar radiation. J. Therm. Anal. 2021, 143, 2789–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasif, M.; Al-Waked, R.; Morrison, G.; Behnia, M. Membrane heat exchanger in HVAC energy recovery systems, systems energy analysis. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, M.; Akbari, S.; Simonson, C.J.; Besant, R.W. Energetic, economic and environmental analysis of a health-care facility HVAC system equipped with a run-around membrane energy exchanger. Energy Build. 2014, 69, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albdoor, A.K.; Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Al-Ghazzawi, F.; Liu, J.; Richardson, C.; Wagner, P. Air-to-air enthalpy exchangers: Membrane modification using metal-organic frameworks, characterisation and performance assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T’Joen, C.; Park, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sommers, A.; Han, X.; Jacobi, A. A review on polymer heat exchangers for HVAC&R applications. Int. J. Refrig. 2009, 32, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, J.; Russeil, S.; Mobtil, M.; Bougeard, D.; Lacrampe, M.-F.; Krawczak, P. High performance finned-tube heat exchangers based on filled polymer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 155, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, E.; Seguro, F.; Filippi, M. Integrated HVAC and DHW production systems for Zero Energy Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 515–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. Research and applications of ultrasound in HVAC field: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Martínez, P.; Martín, Í.; Lucas, M. Numerical Characterization of an Ultrasonic Mist Generator as an Evaporative Cooler. Energies 2020, 13, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Ruiz, J.; Martín, Í.; Lucas, M. Experimental study of an ultrasonic mist generator as an evaporative cooler. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 181, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, B.S.; Mariappan, V.; Maisotsenko, V. Experimental study on combined low temperature regeneration of liquid desiccant and evaporative cooling by ultrasonic atomization. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 112, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Tian, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Thermal performance of a novel ultrasonic evaporator based on machine learning algorithms. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 148, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenari, B.; Carrilho, J.D.; da Silva, M.G. Towards sustainable, energy-efficient and healthy ventilation strategies in buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1426–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Aviv, D.; Guo, H.; Braham, W.W. Measuring the right factors: A review of variables and models for thermal comfort and indoor air quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, D.; Franzitta, V.; Longo, S.; Montana, F.; Sanseverino, E.R. Investigating energy saving potential in a big shopping center through ventilation control. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis, L.L.; Fiorentini, M.; Daly, D. Potential and practical management of hybrid ventilation in buildings. Energy Build. 2021, 231, 110597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.D.; Suh, H.S. Heating and cooling energy consumption prediction model for high-rise apartment buildings considering design parameters. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Chen, Q. Building energy management decision-making in the real world: A comparative study of HVAC cooling strategies. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 33, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Ooka, R.; Kim, J.T.; Nam, Y. Optimization of the HVAC system design to minimize primary energy demand. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; O’Neill, Z.; Cheng, H.; Dong, B. Nationwide HVAC energy-saving potential quantification for office buildings with occupant-centric controls in various climates. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopps, H.; Huchuk, B.; Touchie, M.F.; O’Brien, W. Is anyone home? A critical review of occupant-centric smart HVAC controls implementations in residential buildings. Build. Environ. 2021, 187, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

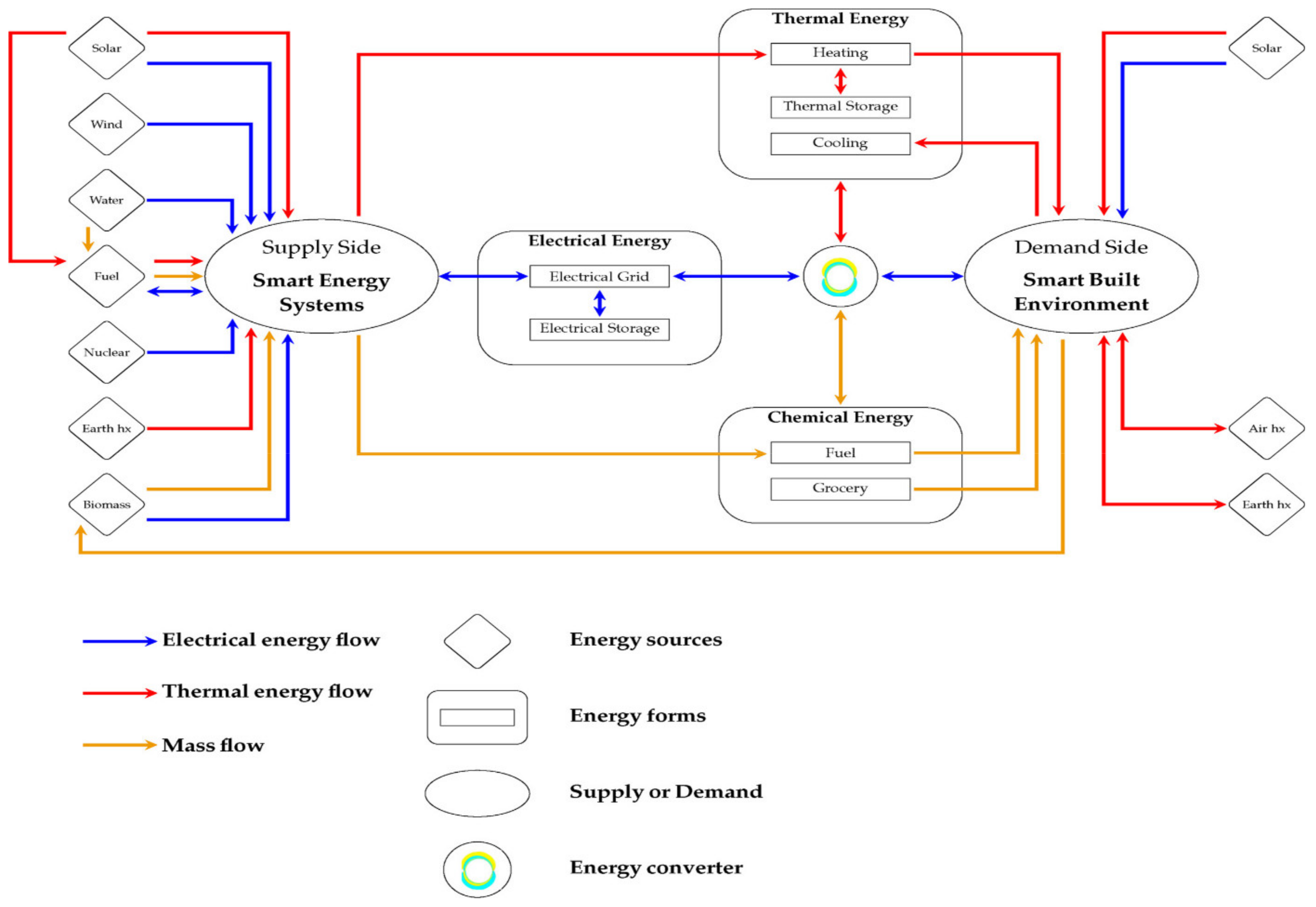

- Su, Y. Smart energy for smart built environment: A review for combined objectives of affordable sustainable green. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bac, U.; Alaloosi, K.A.M.S.; Turhan, C. A comprehensive evaluation of the most suitable HVAC system for an industrial building by using a hybrid building energy simulation and multi criteria decision making framework. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 37, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porowski, M. Energy optimization of HVAC system from a holistic perspective: Operating theater application. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 461–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, Z.; Shafiullah, G.; Urmee, T.; Higgins, G. Modeling techniques used in building HVAC control systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 83, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A.; Wargocki, P.; Rismanchi, B. Ten questions concerning green buildings and indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 2017, 112, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EPA. Indoor Air Quality and Student Performance; United States Environmental Protection Agency, Indoor Environments Division Office of Radiation and Indoor Air: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Katafygiotou, M.; Mazroei, A.; Kaushik, A.; Elsarrag, E. Impact of indoor environmental quality on occupant well-being and comfort: A review of the literature. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che-Ani, A.I.; Tawil, N.M.; Musa, A.R.; Yahaya, H.; Tahir, M.M. The Architecture Studio of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM): Has the Indoor Environmental Quality Standard Been Achieved? Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

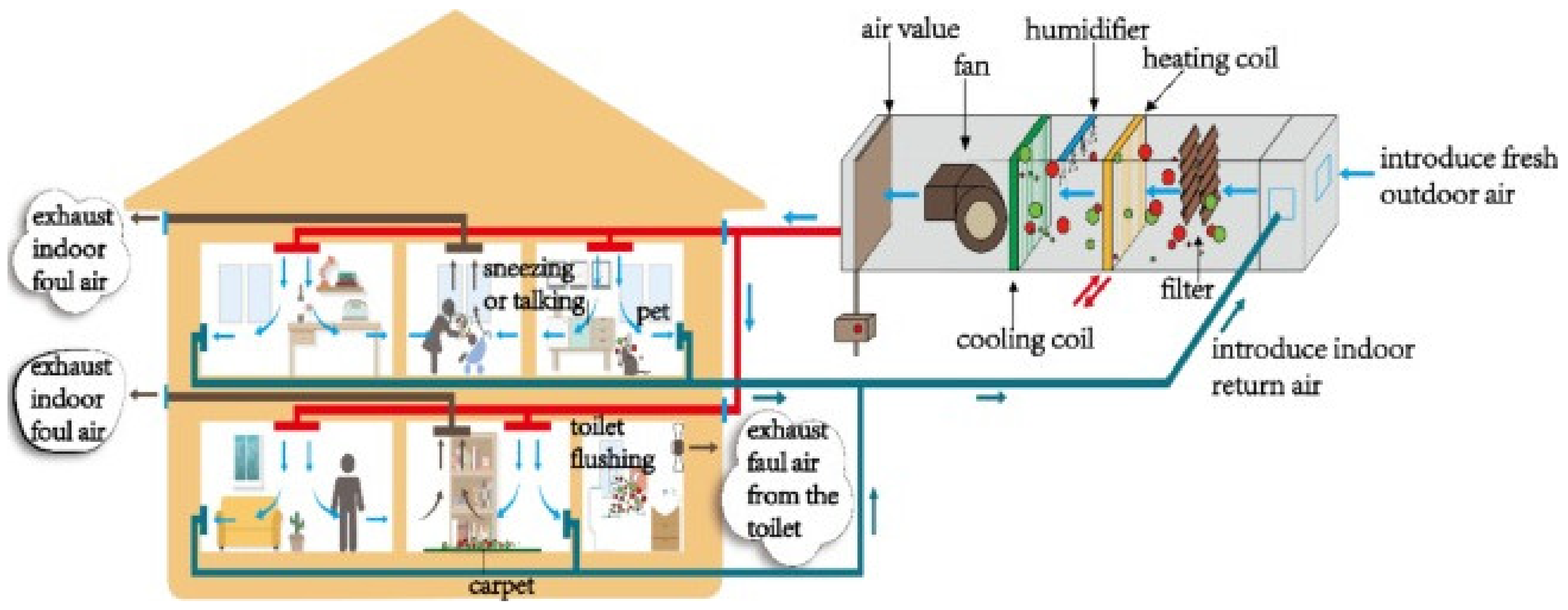

- Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Cao, G.; Meng, C.; He, B.-J. Distribution characteristics, growth, reproduction and transmission modes and control strategies for microbial contamination in HVAC systems: A literature review. Energy Build. 2018, 177, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaali, H.S.; Usman, I.M.S.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Abdulhasan, M.J.; Hamzah, M.T.; Nazal, A.A. Impact of poor indoor environmental quality (Ieq) to inhabitants health, wellbeing and satisfaction. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Roll, I.B.; Halden, R.U.; Pycke, B.F. Indoor air condensate as a novel matrix for monitoring inhalable organic contaminants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 288, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Golpe, M.; Ramil, M.; Cela, R.; Rodríguez, I. Portable dehumidifiers condensed water: A novel matrix for the screening of semi-volatile compounds in indoor air. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.F.O.; Pinto, D.; Enders, M.S.P.; Hower, J.C.; Flores, E.M.M.; Müller, E.I.; Dotto, G.L. Portable dehumidifiers as an original matrix for the study of inhalable nanoparticles in school. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

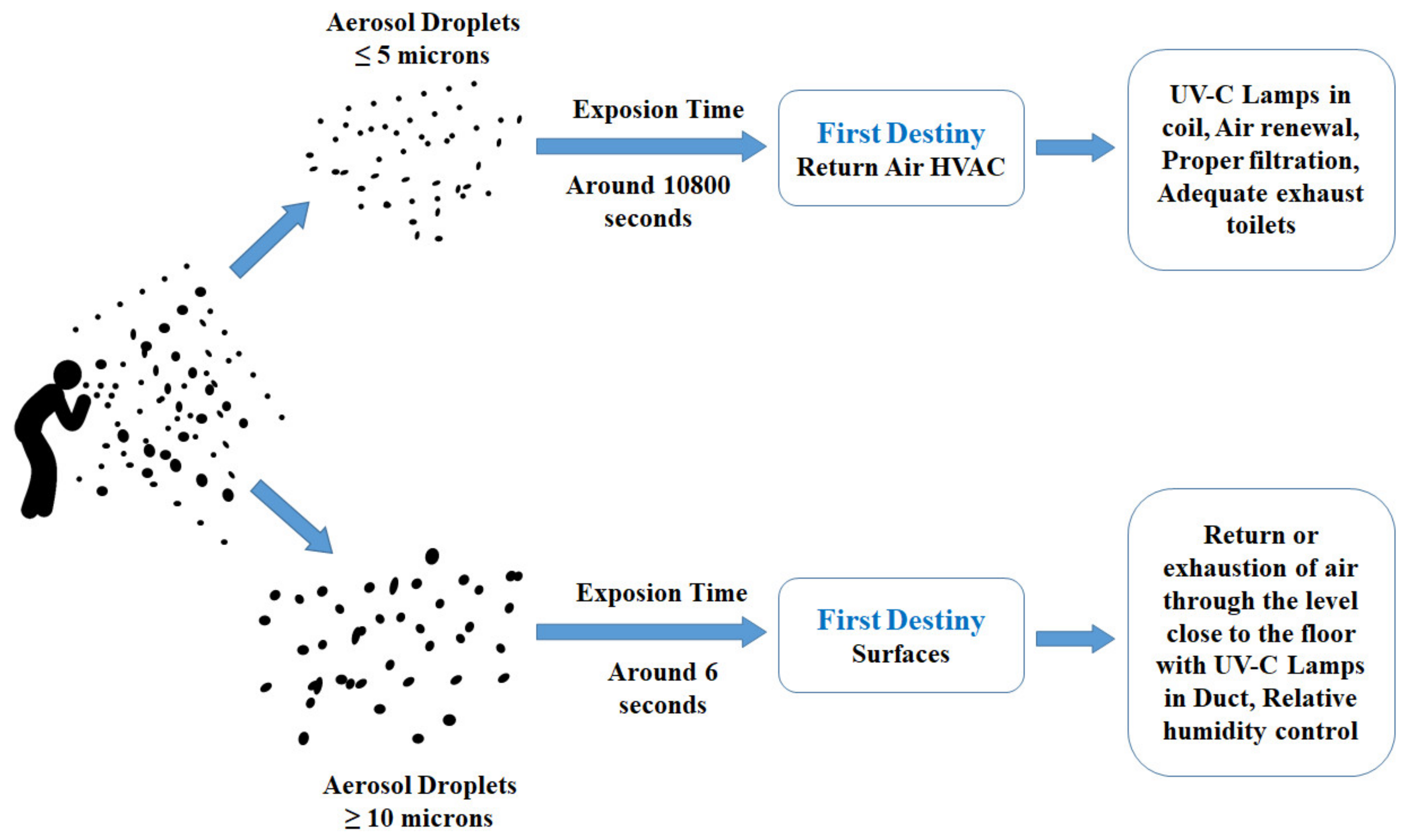

- Santos, A.F.; Gaspar, P.D.; Hamandosh, A.; de Aguiar, E.B.; Filho, A.C.G.; de Souza, H.J.L. Best Practices on HVAC Design to Minimize the Risk of COVID-19 Infection within Indoor Environments. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2020, 63, e20200335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaali, H.S.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Usman, I.M.; Nizam, N.U.M.; Abdulhasan, M.J. A review on green hotel rating tools, indoor environmental quality (Ieq) and human comfort. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 128–157. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Siegel, J.A. Assessing the Impact of Filtration Systems in Indoor Environments with Effectiveness. Build. Environ. 2021, 187, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.K.; Zain, M.; Jamil, M. An environment-friendly solution for indoor air purification by using renewable photocatalysts in concrete: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, X.; Gál, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Pan, S.; Wu, J.; Tang, L.; Clements-Croome, D. A review of air filtration technologies for sustainable and healthy building ventilation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Progress and Expectation of Atmospheric Water Harvesting. Joule 2018, 2, 1452–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, H.M. The Amount of Fresh Water Wasted as by Product of Air Conditioning Systems: Case Study in the Kingdom of Bahrain. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Fourth Industrial Revolution (ICFIR), Manama, Bahrain, 19–21 February 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Algarni, S.; Saleel, C.; Mujeebu, M.A. Air-conditioning condensate recovery and applications—Current developments and challenges ahead. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeebullah, B.A. Potential use of evaporator coils for water extraction in hot and humid areas. Desalination 2009, 237, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, J. Air Conditioning Condensate Recovery. 2021. Available online: https://www.environmentalleader.com/2013/01/air-conditioning-condensate-recovery (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Scalize, P.S.; Soares, S.S.; Alves, A.C.F.; Marques, T.A.; Mesquita, G.G.M.; Ballaminut, N.; Albuquerque, A.C.J. Use of condensed water from air conditioning systems. Open Eng. 2018, 8, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, A.; Cartesegna, M.; Magnani, L.; Cattani, L. Production of Water from the Air: The Environmental Sustainability of Air-conditioning Systems through a More Intelligent Use of Resources. The Advantages of an Integrated System. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magrini, A.; Cattani, L.; Cartesegna, M.; Magnani, L. Water Production from Air Conditioning Systems: Some Evaluations about a Sustainable use of Resources. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tu, R.; Hwang, Y. Performance analyses of a new system for water harvesting from moist air that combines multi-stage desiccant wheels and vapor compression cycles. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 198, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, A.; Cattani, L.; Cartesegna, M.; Magnani, L. Integrated Systems for Air Conditioning and Production of Drinking Water—Preliminary Considerations. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuviella-Suárez, C.; Colmenar-Santos, A.; Borge-Diez, D.; López-Rey, Á. Reduction of water and energy consumption in the sanitary ware industry by an absorption machine operated with recovered heat. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, L.; Magrini, A.; Cattani, P. Water Extraction from Air by Refrigeration—Experimental Results from an Integrated System Application. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghimire, S.R.; Johnston, J.M.; Garland, J.; Edelen, A.; Ma, X.C.; Jahne, M. Life cycle assessment of a rainwater harvesting system compared with an AC condensate harvesting system. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, S.; Morelli, B.; Cashman, S.; Ma, X.; Jahne, M.; Garland, J. Onsite Non-potable Reuse for Large Buildings: Environmental and Economic Suitability as a Function of Building Characteristics and Location. Water Res. 2020, 191, 116635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurubalan, A.; Maiya, M.; Geoghegan, P.J. Tri-generation of air conditioning, refrigeration and potable water by a novel absorption refrigeration system equipped with membrane dehumidifier. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 181, 115861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, A.; Seçkiner, S.U. Optimization of biomass to bioenergy supply chain with tri-generation and district heating and cooling network systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.J.; Son, C.H.; Moon, C.G.; Kong, J.Y. Performance characteristics of portable air conditioner with condensate-water spray. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 675, 12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Z.; Han, L.; Chew, N.G.P.; Chow, W.H.; Wang, R.; Chew, J.W. Membrane distillation hybridized with a thermoelectric heat pump for energy-efficient water treatment and space cooling. Appl. Energy 2018, 231, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, A.; Garcia-Martinez, A.; Sanchez-Montañes, B. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of building refurbishment: A literature review. Energy Build. 2017, 135, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, M.; Baldassarri, C.; Campioli, A.; Giorgi, S.; Valle, A.D.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Benchmarks for environmental impact of housing in Europe: Definition of archetypes and LCA of the residential building stock. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Valentin, V. An Investment Allocation Approach for Building Energy Retrofits. In Construction Research Congress; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2016; pp. 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosi, H.A.; Lavagna, M.; Leonforte, F.; Del Pero, C.; Aste, N. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment in Building Energy Retrofitting; A Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Beccali, M.; Cellura, M.; Mistretta, M. Energy and environmental benefits in public buildings as a result of retrofit actions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, A.; Gabrielli, L.; Scarpa, M. Energy Retrofit in European Building Portfolios: A Review of Five Key Aspects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Valentin, V. An optimization framework for building energy retrofits decision-making. Build. Environ. 2017, 115, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. Energy saving by modification in hvac as a cost saving opportunity for industries. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2013, 4, 3347–3356. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W.; Wei, Z.; Sun, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zang, H.; Chen, S. A conditional value-at-risk-based dispatch approach for the energy management of smart buildings with HVAC systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 188, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Jin, X.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of energy saving potential of HVAC system by operation data with uncertainties. Energy Build. 2019, 204, 109513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technologies | Target | Advantages | Disadvantages | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber filtration | Particles, microorganisms | Low cost, convenient installation | Resistance related to the purification efficiency, mid- and high efficiency of high-resistance filters | Can achieve 99.99% |

| Electrostatic dust removal | Particles, microorganisms | High efficiency and wide range of particle size, small pressure loss | High investment, efficiency decline after dust discharge, easy to breakdown electric field | 50% (some only 20%) |

| Ultraviolet sterilization | Microorganisms | High efficiency, safe and convenient, short reactive time, no residual toxicity, no pollution, low resistance, low cost | Poor dynamic sterilization effect, short service life, UV lamp should be close to the irradiated material, can be influenced by environmental factors, and suspended particles greatly produce secondary pollution | 82.90% |

| Activated carbon adsorption | Nearly all pollutants except biological ones | Wild sources, wide pollutant purifying range, does not easily cause secondary pollution | Saturated regeneration problems, high resistance, poor mineral processing | |

| Plasma | All indoor pollutants | Wide range of pollutants | Cannot completely degrade pollutants, high energy consumption, and production of by-products (ozone and nitrogen oxides) | 66.70%; Cold plasma air filter: 85–98% |

| Negative ions | Particles, microorganisms | Accelerate metabolism, strengthen cell function, effective to some disease | Produce ozone, cause secondary pollution, dust deposition damages walls | 73.40% |

| Photocatalysis | TVOC, microorganisms, and other inorganic gaseous pollutants | Wide range of purification, mild reaction conditions, no adsorption saturation phenomenon, long service life | Compared with the activated carbon adsorption technology, purification process is slower, easily causes secondary pollution if response is not completed, unable to remove particulate pollutants | 75% (some may only 30% or even negative) |

| Trombe wall | Effective particles (diameter) >10 μm and <0.01 μm | 60-year service life | Useless for 0.1–1 μm | 99.4% for PM10 |

| Biofilter | Mixture of VOCs | Effective odor control method | Dynamic botanical air filtration system: >33% for toluene and 90% for formaldehyde; integrated biofiltration system: 99% | |

| Microwave sterilization | Bacterial and fungal aerosols | Heating uniformity, rapid sterilization, and no residue combination of thermal and nonthermal effects; under atmospheric pressure, microwaves can induce argon plasma disinfection | Radiation is harmful to human health | 30–40% of bacterial and fungal aerosols in the environment can survive for 1.7 min under microwave high-power radiation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asim, N.; Badiei, M.; Mohammad, M.; Razali, H.; Rajabi, A.; Chin Haw, L.; Jameelah Ghazali, M. Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021016

Asim N, Badiei M, Mohammad M, Razali H, Rajabi A, Chin Haw L, Jameelah Ghazali M. Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2):1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021016

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsim, Nilofar, Marzieh Badiei, Masita Mohammad, Halim Razali, Armin Rajabi, Lim Chin Haw, and Mariyam Jameelah Ghazali. 2022. "Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 2: 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021016

APA StyleAsim, N., Badiei, M., Mohammad, M., Razali, H., Rajabi, A., Chin Haw, L., & Jameelah Ghazali, M. (2022). Sustainability of Heating, Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Systems in Buildings—An Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19021016