Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship: Identity-Informed Recommendations to Improve the Quality of Life of African American Breast Cancer Survivors in Health Promotion Programming

Abstract

:1. Introduction

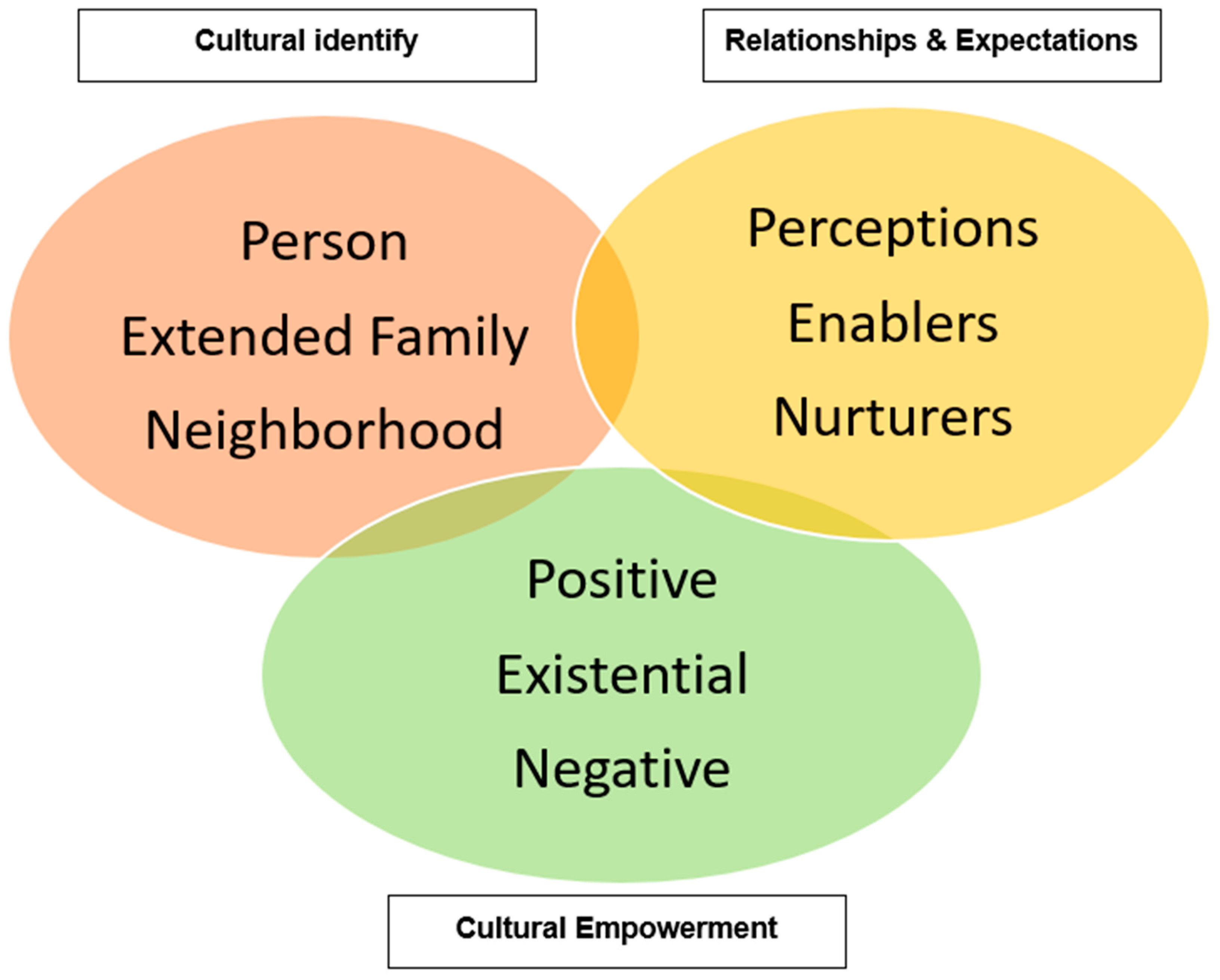

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sample

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Focus Group Findings

3.2.1. Theme 1. Caregiving Roles Provide Both Support and Challenges for Survivors

“Because I tell my grand babies I live for them. They is what gives me joy. They is what give me the strength I need because when I feel depressed, I feel lonely, I feel like I don’t want to go outside, I don’t want to make no phone call, I got to keep it real … And then when I get that phone call or they just pop up at my door, there it is. It’s like … something just click. You know what I’m saying? And my grandkids is what give me life. And I tell them that all the time, ‘I live for y’all. Y’all give me the strength, the joy that I need to keep keeping on.’”

“‘Go back, grandma. You gonna fall out and who gonna pick you up! … Go back, grandma … it’s slick out here,’ he can tell me, ‘You gonna fall and who gonna pick you up?’ I said, ‘You gonna get me up…’ But I- it’s- that keeps me going.”

“Yup. I did, because I put my foot down with my son and told him … ‘You got to come get your kids. I’ve gotta bathe them, I gotta feed them. I’m getting old, tired, whatever.’ And I’m like that, getting so I can’t go through this … I can’t cuz I get too tired. I be so tired … I said, ‘Y’all gonna send me to my grave early.’”

“My stuff is always, my husband’s, nothin’s never wrong. They always pass it all on to me. Um. I don’t know. I work every day. I take care of my mom. She’s 94. And I’m not, I’m busy doin’ whatever I need to do. Drive. Do normal. Men think we’re invincible, so, you know, do what you have to do.”

3.2.2. Theme 2. The Strong Black Woman Is Inherent in Survivor Experiences

“Because even through all this I’m goin through I still manage to be there for my sister, my family. You know, I’m doin that. Because I’m strong enough to do it. Even when I was like really sick and from like all we need to be, I was out there tryin to do somethin’.”

“I didn’t want to hurt them. And I didn’t tell anybody in the family … Because I was afraid I would devastate them … And I lived with it for that year and then when I did tell them, that devastated them more.”

“I couldn’t come out my house for almost two years … after that … I was having really panic attacks and instead like I would just get really hot. It felt like, you know how you could be in a, uh, the lunchroom, how you just hear voices, just you hear everything everybody is saying…”

3.2.3. Theme 3. Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship

“I don’t mind exposing his name because he deserved exposing, Dr. XX at the time, was at the XYZ hospital but wouldn’t come and see me. And um, so I got out of the hospital and I went to his office and I asked why didn’t you come and see me. He said “Well, there’s nothing we can do for you.” And my husband was like “Man, you her doctor, why wouldn’t you come and at least check in on your patient, and we actually saw you walking around the hall and you totally ignored her.”

‘’I had that experience with one of my oncologists when I went through my cancer thing and it really, really hurt my feelings just the fact that he had, didn’t quite acknowledge me, um, you know when I was in his office getting chemo. One day I was sitting for some test that he had referred me to and he walked right past me like he didn’t even know who I was. And you know, seeing his face every day for chemo. So when he did that to me and he didn’t acknowledge the face and then every time I came with him with questions, he just like brushed it off. He- it’s like my family would ask him things about me and what I was going through and he just- he wouldn’t give us answers. He just basically just brushed it off.”

“I don’t know, if you want to do something you have to go so far out, stores have moved out of the neighborhoods … Because it used to be, maybe it still, can you go, you used to be able to go to market, general hospital or whatever, but they’ve moved. All of those things, out of your neighborhood. You don’t have access to it.”

3.2.4. Theme 4. African American Women RESIST Oppression through Culturally Specific Support and Advocacy

“Like my cousin, she throws a pink party every year, and it’s just for people in the family to come, and she has like brassieres and stuff like this just to inform them, educate, because, you know, back in the day it was something you didn’t really know about. You shied away. You thought it was something negative. But there’s more information now. And we have to be that support system. You don’t know who’s next? So you have to build each other up and inform. We’ve got to get this education.”

“You know, I’ma live or die, but so in the meanwhile, it’s full, the doors open for me to challenge whatever I face and my family faces and my community faces that I don’t think is right. So, it gave me a voice and that was the part about staying strong because in order to have a voice, you have to stay strong.”

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foy, K.C.; Fisher, J.L.; Lustberg, M.B.; Gray, D.M.; DeGraffinreid, C.R.; Paskett, E.D. Disparities in breast cancer tumor characteristics, treatment, time to treatment, and survival probability among African American and white women. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paskett, E.D.; Alfano, C.M.; Davidson, M.A.; Andersen, B.L.; Naughton, M.J.; Sherman, A.; McDonald, P.G.; Hays, J. Breast cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life: Racial differences and comparisons with noncancer controls. Cancer 2008, 113, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Yoo, W.; Whitehead, M.S.; Smith, S.A. Advancing breast cancer survivorship among African-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 153, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collins, P.H. Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought. Soc. Probl. 1986, 33, S14–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, P.H. The Social Construction of Black Feminist Thought; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Defining Black Feminist Thought; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, B.; Wambach, K.; Domain, E.W. African American Women’s Breastfeeding Experiences: Cultural, Personal, and Political Voices. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 25, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, E.; Deal, E.; Lopez, A.A.; Dressel, A.E.; Graf, M.D.C.; Schmitt, M.; Hawkins, M.; Pittman, B.; Kako, P.; Mkandawire-Valhmu, L. Successful substance use disorder recovery in transitional housing: Perspectives from African American women. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 30, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaway, A.T.; Ward, L.W.; Howell, D. Black girls and womyn matter: Using Black feminist thought to examine violence and erasure in education. Urban Educ. Res. Policy Annu. 2019, 6, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.P.; Javier, S.J.; Maxwell, M.L.; Dunn, C.E.; Belgrave, F.Z. “You put yourself at risk to keep the relationship:” African American women’s perspectives on womanhood, relationships, sex and HIV. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 24, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour-Burton, T.; Etland, C. Black Feminist Thought: A Paradigm to Examine Breast Cancer Disparities. Nurs. Res. 2020, 69, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, I.H. Use of an Intersectional Framework to Understand Black Women’s Racial and Gender Identities. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev. 1990, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Culture Matters in Global Health. Eur. Health Psychol. 2010, 12, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Health and Culture: Beyound the Western Paradigm; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor, J.; Newsome, V.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Framing the impact of culture on health: A systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethn. Health 2014, 19, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kline, K.N. Cultural Sensitivity and Health Promotion: Assessing Breast Cancer Education Pamphlets Designed for African American Women. Health Commun. 2007, 21, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochs-Balcom, H.M.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Erwin, D.O. Establishing a community partnership to optimize recruitment of African American pedigrees for a genetic epidemiology study. J. Community Genet. 2011, 2, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adegboyega, A.; Aroh, A.; Voigts, K.; Jennifer, H. Regular Mammography Screening Among African American (AA) Women: Qualitative Application of the PEN-3 Framework. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Williams, K.P.; Harrison, T.M.; Jennings, Y.; Lucas, W.; Stephen, J.; Robinson, D.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Taylor, K.L. Development of decision-support intervention for Black women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.T.; Padilla, G.; Tejero, J.; Kraemer, J.; Wright, K.; Coscarelli, A.; Clayton, S.; Williams, I.; Hills, D. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. J. Psychol. Soc. Behav. Dimens. Cancer 2004, 13, 408–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.L.; Roth, D.L.; Huang, J.; Park, C.L.; Clark, E.M. Longitudinal effects of religious involvement on religious coping and health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.; Okoror, T.; Shefer, T.; Brown, D.; Iwelunmor, J.; Smith, E.; Adam, M.; Simbayi, L.; Zungu, N.; Dlakulu, R.; et al. Stigma, Culture, and HIV and AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: An Application of the PEN-3 Cultural Model for Community-Based Research. J. Black Psychol. 2009, 35, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. Emergence vs Forcing: Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, R.A.; West, L.M. Stress and Mental Health: Moderating Role of the Strong Black Woman Stereotype. J. Black Psychol. 2014, 41, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Chae, D.H.; Price, M.M.; Powell, W.; Steed, T.C.; Rose Black, A.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Marquez-Magaña, L.; Woods-Giscombe, C.L. Racial discrimination, the superwoman schema, and allostatic load: Exploring an integrative stress-coping model among African American women. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place 2010, 16, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Unequal Gain of Equal Resources across Racial Groups. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2018, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, A. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2002, 94, 666. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Rucker, T.D. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2000, 21, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nicks, S.E.; Wray, R.J.; Peavler, O.; Jackson, S.; McClure, S.; Enard, K.; Schwartz, T. Examining peer support and survivorship for African American women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risendal, B.C.; Dwyer, A.; Seidel, R.W.; Lorig, K.; Coombs, L.; Ory, M.G. Meeting the challenge of cancer survivorship in public health: Results from the evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program for cancer survivors. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fong, A.J.; Scarapicchia, T.M.F.; McDonough, M.H.; Wrosch, C.; Sabiston, C.M. Changes in social support predict emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, M.; Nemeth, L. Transition from patient to survivor in African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2015, 38, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, I.M.; Yoo, G.J.; Levine, E.G. Keeping us all whole: Acknowledging the agency of African American breast cancer survivors and their systems of social support. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2625–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, Y.R. “We’re Different, and It’s Okay That We’re Different.” Long-Term Breast Cancer Survivorship among African American Women. J. Best Pract. Health Prof. Divers. 2017, 10, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby, W.; Bally, J.; Cooper, D.; Doell, H.; Thomas, R. Engaging hope: The experiences of male spouses of women with breast cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonçalves, J.P.; Lucchetti, G.; Menezes, P.R.; Vallada, H. Religious and spiritual interventions in mental health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 2937–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, S.M.; Afifi, T.D. The Strong Black Woman Collective Theory: Determining the Prosocial Functions of Strength Regulation in Groups of Black Women Friends. J. Commun. 2019, 69, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Costa, M.V.; Odunlami, A.O.; Mohammed, S.A. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2008, 14, S8–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garza, R.H.; Williams, M.Y.; Ntiri, S.O.; Hampton, M.D.; Yan, A.F. Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship: Identity-Informed Recommendations to Improve the Quality of Life of African American Breast Cancer Survivors in Health Promotion Programming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912807

Garza RH, Williams MY, Ntiri SO, Hampton MD, Yan AF. Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship: Identity-Informed Recommendations to Improve the Quality of Life of African American Breast Cancer Survivors in Health Promotion Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912807

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarza, Rose Hennessy, Michelle Y. Williams, Shana O. Ntiri, Michelle DeCoux Hampton, and Alice F. Yan. 2022. "Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship: Identity-Informed Recommendations to Improve the Quality of Life of African American Breast Cancer Survivors in Health Promotion Programming" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912807

APA StyleGarza, R. H., Williams, M. Y., Ntiri, S. O., Hampton, M. D., & Yan, A. F. (2022). Intersectionality Impacts Survivorship: Identity-Informed Recommendations to Improve the Quality of Life of African American Breast Cancer Survivors in Health Promotion Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12807. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912807