Evaluating the Effects of Denmark’s New Tobacco Control Act on Young People’s Use of Nicotine Products: A Study Protocol of the §SMOKE Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Legislation

1.2. §SMOKE–A Study of Tobacco, Behavior, and Regulations

1.2.1. Increased Tobacco Prices

1.2.2. Point-of-Sale (POS) Display Ban

1.2.3. Plain Packaging

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Timing of Data Collection

2.3. Study Sample

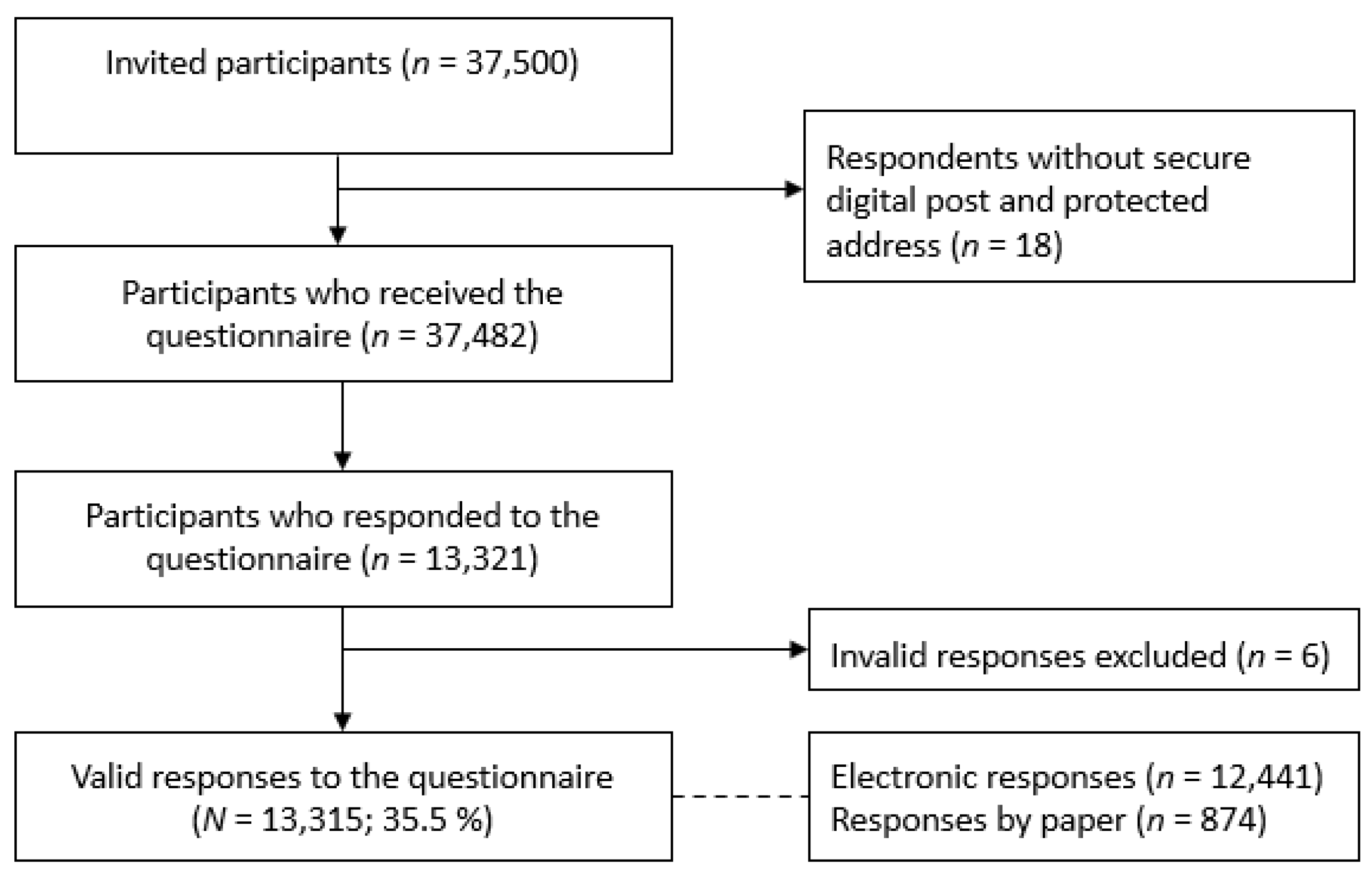

2.4. Sample for Baseline Survey

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. The Questionnaire

2.7. Demographic Information from Registers

2.8. Data Analysis

- (1)

- The prevalence of smoking and use of specific tobacco and nicotine products between baseline and follow-up surveys in the subsequent years, including dual and multiple product use;

- (2)

- Increased tobacco prices, i.e., smoking intensity, transition from daily to occasional smoking or no smoking, quitting attempts and cessation, effects in subgroups;

- (3)

- POS display ban, i.e., perceived availability of products, brand awareness, smoking norms, temptation to buy products, and changes in attitudes towards smoking;

- (4)

- Plain packaging, i.e., package appeal, noticing packages, covering up packages.

2.9. Weighting

3. Discussion

Methodological Issues

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Capacity Assessment on the Implementation of Effective Tobacco Control Policies in Denmark 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, H.A.R.; Davidsen, M.; Ekholm, O.; Christensen, A.I. National Health Profile in Denmark 2017; The National Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018.

- Brink, A.-L.; Stage, M. Røgfri Fremtids Ungeundersøgelse 2017–2020 [The Youth Study of Smokefree Future 2017–2020]. 2021. Available online: https://www.cancer.dk/dyn/resources/File/file/8/9138/1613110824/roegfri_ungeundersoegelse_2017-20_final_final-003.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- The Danish Health Authority. Smoking Habits of Danish Citizens 2020, Report 1: Nicotine Dependence; Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jarlstrup, N.S.; Andersen, M.B.; Kjeld, S.G.; Bast, L.S. § RØG—En Undersøgelse af Tobak, Adfærd og Regler: Basisrapport 2020. [§Smoke—A Study of Tobacco, Behavior, and Regulations: Baseline Report 2020]; Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.B.; Bast, L.S. § RØG-En Undersøgelse af Tobak, Adfærd og Regler: Udvalgte Tendenser 2021. [§Smoke—A Study of Tobacco, Behavoir, and Regulations: Tendencies in 2021]; Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.N.; Kraemer, J.D.; Johnson, A.C.; Mays, D. Plain packaging of cigarettes: Do we have sufficient evidence? Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2015, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, M.A.; Best, C.; Wilson, M.; Currie, D.; Ozakinci, G.; Mackintosh, A.-M.; Stead, M.; Eadie, D.; MacGregor, A.; Pearce, J.; et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of tobacco accessibility and smoking norms and attitudes in response to the tobacco point-of-sale display ban in Scotland: Results from the DISPLAY Study. Tob. Control. 2020, 29, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Guidelines for Implementation of Article 5. 3, Articles 8 To 14; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, L.; Davidsen, M.; Jensen, H.A.R.; Ryd, J.T.; Strøbæk, L.; White, E.D.; Sørensen, J.; Juel, K. Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark: Risikofaktorer [The Disease Burden in Denmark—Risk Factors]; The Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016.

- Gormsen, C. Løhde: Vi Skal Have Første Røgfrie Generation i 2030; Altinget: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kjær, N.T. Smoke-Free Future in Denmark. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2020, 6, A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestbo, J.; Pisinger, C.; Bast, L.S.; Gyrd-Hansen, D. Forebyggelse af Rygning Blandt Børn Og Unge. Hvad Virker? [Prevention Smoking Among Children and Youth. What Works?]; Vidensråd for Forebyggelse: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesen, C.K.; Andersen, S.; Bast, L.S. Estimating future smoking in Danish youth–effects of three prevention strategies. Scand. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannesen, C.K.; Andersen, S.; Bast, L.S. Veje Til et Røgfrit Ungeliv: Betydningen af Tre Tiltag Til Forebyggelse af Rygning Blandt Børn og Unge-Fremskrivninger Til 2030. [A smoke Free Youth Life: The Meaning of Three Preventive Initiatives Among Youth]; The Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

- The Ministry of Health. Handleplan Mod Børn og Unges Rygning. 2019. Available online: https://www.regeringen.dk/nyheder/2019/handleplan-mod-boern-og-unges-rygning/] (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Chaloupka, F.J.; Straif, K.; Leon, M.E. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob. Control. 2011, 20, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hasselt, M.; Kruger, J.; Han, B.; Caraballo, R.S.; Penne, M.A.; Loomis, B.; Gfroerer, J.C. The relation between tobacco taxes and youth and young adult smoking: What happened following the 2009 US federal tax increase on cigarettes? Addict. Behav. 2015, 45, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloupka, F.J.; Bank, W. Curbing the epidemic: Governments and the economics of tobacco control. Tob. Control. 1999, 8, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing New and Emerging Products; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Laverty, A.A.; Vamos, E.P.; Millett, C.; Chang, K.C.; Filippidis, F.T.; Hopkinson, N.S. Child awareness of and access to cigarettes: Impacts of the point-of-sale display ban in England. Tob. Control. 2019, 28, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynter, J.; Edwards, R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009, 11, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, L.; McGee, R.; Marsh, L.; Hoek, J. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Moodie, C.; Kuipers, M.A.; Hastings, G.B.; Bauld, L. Impact of a ban on the open display of tobacco products in retail outlets on never smoking youth in the UK: Findings from a repeat cross-sectional survey before, during and after implementation. Tob. Control. 2020, 29, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babineau, K.; Clancy, L. Young people’s perceptions of tobacco packaging: A comparison of EU Tobacco Products Directive & Ireland’s Standardisation of Tobacco Act. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McNeill, A.; Gravely, S.; Hitchman, S.C.; Bauld, L.; Hammond, D.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Tobacco packaging design for reducing tobacco use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD011244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodie, C.; Hoek, J.; Scheffels, J.; Gallopel-Morvan, K.; Lindorff, K. Plain packaging: Legislative differences in Australia, France, the UK, New Zealand and Norway, and options for strengthening regulations. Tob. Control. 2019, 28, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Plain Packaging of Tobacco Products: Evidence, Design and Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, C.B. The Danish civil registration system. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39 (Suppl. 7), 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Danskernes Rygevaner 2019 [Danes’ Smoking Habits in 2019]; The Danish Health Authority: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020.

- Christensen, A.I.; Ekholm, K.O.M.; Glümer, C.; Andreasen, A.H.; Hvidberg, M.F.; Kristensen, P.L.; Larsen, F.B.; Ortiz, B.; Juel, K. The Danish national health survey 2010. Study design and respondent characteristics. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A.I.; Lau, C.J.; Kristensen, P.L.; Johnsen, S.B.; Wingstrand, A.; Friis, K.; Davidsen, M.; Andreasen, A.H. The Danish National Health Survey: Study design, response rate and respondent characteristics in 2010, 2013 and 2017. Scand. J. Public Health 2020, 50, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomber, K.; Zacher, M.; Durkin, S.; Brennan, E.; Scollo, M.; Wakefield, M.; Myers, P.; Vickers, N.; Mission, S. Australian National Tobacco Plain Packaging Tracking Survey: Technical Report; Cancer Council Victoria and Social Research Centre Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agaku, I.T.; Omaduvie, U.T.; Filippidis, F.T.; Vardavas, C.I. Cigarette design and marketing features are associated with increased smoking susceptibility and perception of reduced harm among smokers in 27 EU countries. Tob. Control. 2015, 24, e233–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffels, J.; Lavik, R. Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tob. Control. 2013, 22, e37–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeld, S.G.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Aundal, M.; Bast, L.S. Price elasticity of demand for cigarettes among youths in high-income countries: A systematic review. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 14034948211047778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Shang, C.; Huang, J.; Cheng, K.W.; Chaloupka, F.J. Global evidence on the effect of point-of-sale display bans on smoking prevalence. Tob. Control. 2018, 27, e98–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Huang, J.; Cheng, K.W.; Li, Q.; Chaloupka, F.J. Global Evidence on the Association between POS Advertising Bans and Youth Smoking Participation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, J.M.; Ollila, H.; Linnansaari, A.; Timberlake, D.S.; Kuipers, M.A.G.; Rimpelä, A.H. Adolescents notice fewer tobacco displays after implementation of the point-of-sale tobacco display ban in Finland. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haw, S.; Amos, A.; Eadie, D.; Frank, J.; MacDonald, L.; MacKintosh, A.M.; MacGregor, A.; Miller, M.; Pearce, J.; Sharp, C.; et al. Determining the impact of smoking point of sale legislation among youth (Display) study: A protocol for an evaluation of public health policy. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.; Cherrie, M.; Best, C.; Eadie, D.; Stead, M.; Amos, A.; Currie, D.; Ozakinci, G.; MacGregor, A.; Haw, S. How has the introduction of point-of-sale legislation affected the presence and visibility of tobacco retailing in Scotland? A longitudinal study. Tob. Control. 2020, 29, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravely, S.; Chung-Hall, J.; Craig, L.V.; Fong, G.T.; Cummings, K.M.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Loewen, R.; Martin, N.; Quah, A.C.K.; et al. Evaluating the impact of plain packaging among Canadian smokers: Findings from the 2018 and 2020 ITC Smoking and Vaping Surveys. Tob. Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.C.; Luta, G.; Tercyak, K.P.; Niaura, R.S.; Mays, D. Effects of pictorial warning label message framing and standardized packaging on cigarette packaging appeal among young adult smokers. Addict. Behav. 2021, 120, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentala, J.; Utriainen, P.; Pahkala, K.; Mattila, K. Verification of adolescent self-reported smoking. Addict. Behav. 2004, 29, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, R.S.; Giovino, G.A.; Pechacek, T.F. Self-reported cigarette smoking vs. serum cotinine among US adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004, 6, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisinger, V.; Thorsted, A.; Jezek, A.H.; Jørgensen, A.; Christensen, A.I.; Thygesen, L.C. Sundhed og Trivsel på Gymnasiale Uddannelser 2019 [Health and Wellbeing in High Schools 2019]; National Institute of Public Health: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

| Legislations | Details | Came into Effect |

|---|---|---|

| First increase in tobacco prices | The average price of a pack (20 PCS) of cigarettes increased from 40 DKK/5.35 EUR to 55 DKK/7.36 EUR (37.5% increase) | 1 April 2020 |

| Menthol flavor ban (Tobacco Products Directive) | Ban on cigarettes and RYO tobacco with a characterizing flavor of menthol | 20 May 2020 |

| Smoke-free school hours | No smoking during the school day in primary school, even outside school premises | 1 January 2021 |

| Point-of-sale display ban | No display of tobacco products, herbal products, e-cigarettes, or nicotine products at points of sale in retail outlets | 1 April 2021 |

| Ban on flavors other than tobacco and menthol | A proposed ban on flavors other than tobacco and menthol in other tobacco products than cigarettes and RYO (e.g., chewing tobacco, heated tobacco, and shisha/waterpipe) was planned, but this currently awaits a decision by the European Commission | Temporarily suspended |

| Smoke-free-school-hours | No smoking during school hours in high schools and vocational schools, even outside school premises | 31 July 2021 |

| Second increase in tobacco prices | Increase in the average price of a pack (20 PCS) of cigarettes from DKK 55/EUR 7.36 to DKK 60/EUR 8.02 (9% increase) | 1 January 2022 |

| Ban on flavors other than tobacco and menthol in e-liquids | A ban on flavors other than tobacco and menthol in e-liquids used in e-cigarettes | 1 April 2022 |

| Plain packaging of all forms of tobacco including cigarettes, RYO tobacco, chewing tobacco, heated tobacco and waterpipe tobacco | Transition period: 1 July 2021 until 1 April | 1 April 2022 |

| Plain packaging of e-cigarettes | Transition period: 1 October 2021 until 1 October 2022 | 1 October 2022 |

| Definition of tobacco surrogates, including nicotine containing products which are not medically approved for smoking cessation. Tobacco surrogates are in general covered by the same legislation as tobacco products except standardized packaging and the suggested flavor ban. This includes nicotine pouches | 1 July 2022 | |

| Topics | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | Gender, age, highest level of educational attainment, living status (alone, with parents, etc.) |

| Quality of life | Quality of life, physical and mental health, and well-being |

| Cigarette use | Current smoking status, smoking frequency and quantity, age at regularly smoking, flavor additives, quit attempts and intentions, intention to smoke (again), perception of smoking as acceptable, smoking in the family and among relatives |

| Other tobacco and nicotine products | Products: E-cigarettes, smoke-free tobacco (e.g., nicotine pouches), water pipe, cigarillos, heated tobaccoTobacco and nicotine use–frequency and type of product, flavor additives, perception of health risk, quit attempts and intentions |

| Increased cigarette prices | Where to buy cigarettes, purchase price, factory-made or ROY cigarettes, smokers self-assessed effect of increased price on frequency of smoking, financial stress (shortage of money) |

| POS display ban | Notification of visible tobacco products in retail establishments, social media, movies, or the internet in the past month |

| Plain packaging | Brand awareness, perceptions of quality, satisfaction, taste, value for money, harmfulness, the appeal of the package, risk for addiction and type of cigarette (‘light’, slim, organic, etc.), concerns about health effects, notification of health warnings |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klitgaard, M.B.; Jarlstrup, N.S.; Lund, L.; Brink, A.-L.; Knudsen, A.; Christensen, A.I.; Bast, L.S. Evaluating the Effects of Denmark’s New Tobacco Control Act on Young People’s Use of Nicotine Products: A Study Protocol of the §SMOKE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912782

Klitgaard MB, Jarlstrup NS, Lund L, Brink A-L, Knudsen A, Christensen AI, Bast LS. Evaluating the Effects of Denmark’s New Tobacco Control Act on Young People’s Use of Nicotine Products: A Study Protocol of the §SMOKE Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912782

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlitgaard, Marie Borring, Nanna Schneekloth Jarlstrup, Lisbeth Lund, Anne-Line Brink, Astrid Knudsen, Anne Illemann Christensen, and Lotus Sofie Bast. 2022. "Evaluating the Effects of Denmark’s New Tobacco Control Act on Young People’s Use of Nicotine Products: A Study Protocol of the §SMOKE Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912782

APA StyleKlitgaard, M. B., Jarlstrup, N. S., Lund, L., Brink, A.-L., Knudsen, A., Christensen, A. I., & Bast, L. S. (2022). Evaluating the Effects of Denmark’s New Tobacco Control Act on Young People’s Use of Nicotine Products: A Study Protocol of the §SMOKE Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912782