Factors Associated with Uptake of Effective and Ineffective Contraceptives among Polish Women during the First Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How often do women choose effective and ineffective contraceptive methods?

- Which demographic, social, cultural, and sexual factors correlate with decisions about the choice of more or less effective family planning method in the univariate analysis?

- Which variables predict that choice in the multivariate analysis?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Strategy to accelerate progress towards the attainment of international development goals and targets related to reproductive health. Reprod. Health Matters 2005, 13, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finer, L.B.; Zolna, M.R. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finer, L.B.; Zolna, M.R. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104 (Suppl. S1), S43–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, D. The FIGO initiative for the prevention of unsafe abortion. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2010, 110, S17–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, C. Sexual behaviour and sexual and reproductive health education: A cross-sectional study in Romania. Reprod. Health 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Izdebski, Z. Seksualność Polaków na Początku XXI Wieku: Studium Badawcze; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Cracow, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schivone, G.B.; Glish, L.L. Contraceptive counseling for continuation and satisfaction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, A.; Vaughan, B.; Kost, K.; Bankole, A.; Finer, L.; Singh, S.; Trussell, J. Contraceptive Failure in the United States: Estimates from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2017, 49, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finer, L.B.; Jerman, J.; Kavanaugh, M.L. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual & Reproductive Rights. Contraception Policy Atlas Europe. Available online: https://www.epfweb.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/CCeptionInfoA3_EN%202022%20MAR2%20LoRes%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Walker, S.H. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on contraceptive prescribing in general practice: A retrospective analysis of English prescribing data between 2019 and 2020. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. COVID 19 era: A beginning of upsurge in unwanted pregnancies, unmet need for contraception and other women related issues. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2020, 25, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolu, L.B.; Feyissa, G.T.; Jeldu, W.G. Guidelines and best practice recommendations on reproductive health services provision amid COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.K.; Law, R.; Beaman, J.; Foster, D.G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic security and pregnancy intentions among people at risk of pregnancy. Contraception 2021, 103, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCool-Myers, M.; Kozlowski, D.; Jean, V.; Cordes, S.; Gold, H.; Goedken, P. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on sexual and reproductive health in Georgia, USA: An exploration of behaviors, contraceptive care, and partner abuse. Contraception 2022, 113, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, U.; Hopkins, J. Family Planning: Global Handbook for Providers; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; USAID: Washington, DC, USA; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/public/publications/pid/397 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Pearl, R. Factors in Human Fertility and Their Statistical Evaluation; Lancet: London, UK, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Nagelkerke, N.J.D. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991, 78, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S.; Pinchoff, J.; Ngo, T.D.; Hindin, M.J. The impact of natural disasters and epidemics on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries: A narrative synthesis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 157, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarger, J.; Hopkins, K.; Elmes, S.; Rossetto, I.; De La Melena, S.; McCulloch, C.E.; White, K.; Harper, C.C. Perceived Access to Contraception via Telemedicine Among Young Adults: Inequities by Food and Housing Insecurity. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2022, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, T.; Sully, E.; Ahmed, Z.; Biddlecom, A. Estimates of the Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sexual and Reproductive Health In Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 46, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellizzi, S.; Pichierri, G.; Napodano, C.M.P.; Picchi, S.; Fiorletta, S.; Panunzi, M.G.; Rubattu, E.; Nivoli, A.; Lorettu, L.; Amadori, A.; et al. Access to modern methods of contraception in Italy: Will the COVID-19 pandemic be aggravating the issue? J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izdebski, Z. Zdrowie i Życie Seksualne Polek i Polaków w Wieku 18-49 lat w 2017 Roku. Studium Badawcze na tle Przemian od 1997 Roku; Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N.; Amin, M.B.; Maliha, M.J.; Sarker, B.; Aktarujjaman, M.; Hossain, E.; Talukdar, G. Prevalence and factors associated with family planning during COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Larios, F.; Silva Reus, I.; Lahoz Pascual, I.; Quilez Conde, J.C.; Puente Martinez, M.J.; Gutierrez Ales, J.; Correa Rancel, M. Women’s Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.A.; Kottke, M.J.; Berlan, E.D. Providing Contraception for Young People During a Pandemic Is Essential Health Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 823–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolarinwa, O.A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.A.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Saeed, B.Q.; Hagan, J.E., Jr.; Nwagbara, U.I. Mapping Evidence of Impacts of COVID-19 Outbreak on Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balachandren, N.; Barrett, G.; Stephenson, J.M.; Yasmin, E.; Mavrelos, D.; Davies, M.; David, A.; Hall, J.A. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on access to contraception and pregnancy intentions: A national prospective cohort study of the UK population. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 48, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandell, K.; Vanbenschoten, H.; Parachini, M.; Gomperts, R.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. Telemedicine as an alternative way to access abortion in Italy and characteristics of requests during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2021, 25, bmjsrh-2021-201281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; Minona, P. Sexual activity and contraceptive use during social distancing and self-isolation in the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2020, 25, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, B.; Ozgor, F. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–25 years old (y.o.) | 155 | 24.1 |

| 26–34 y.o. | 182 | 28.3 |

| 35–41 y.o. | 151 | 23.5 |

| 42–49 y.o. | 154 | 24.0 |

| Education level | ||

| under vocational | 66 | 10.3 |

| vocational | 232 | 36.1 |

| secondary | 212 | 33.0 |

| higher | 132 | 20.6 |

| Place of residence | ||

| country | 300 | 46.7 |

| city | 342 | 53.3 |

| Attitude towards faith | ||

| believers who practice regularly | 106 | 16.5 |

| believers who practice irregularly | 186 | 29.0 |

| non-practicing believers | 228 | 35.5 |

| unbelievers | 78 | 12.1 |

| not specified or refusal to answer | 44 | 6.9 |

| Economic status | ||

| very bad | 39 | 6.1 |

| relative or average | 371 | 57.8 |

| good or very good | 215 | 33.5 |

| refusal to answer | 17 | 2.6 |

| Occupation status | ||

| professional works | 333 | 51.8 |

| learns | 45 | 7.0 |

| runs the house | 157 | 24.5 |

| a pension or not working | 89 | 13.9 |

| refusal to answer | 18 | 2.8 |

| Relationship status | ||

| formal | 324 | 50.5 |

| informal | 266 | 41.4 |

| out of the relationship | 44 | 6.9 |

| refusal to answer | 8 | 1.2 |

| The number of sexual partners in a lifetime | ||

| one | 138 | 23.3 |

| 2–3 | 238 | 40.1 |

| 4 or more | 217 | 36.6 |

| no data | 49 | |

| Children | ||

| any | 473 | 73.7 |

| no | 169 | 26.3 |

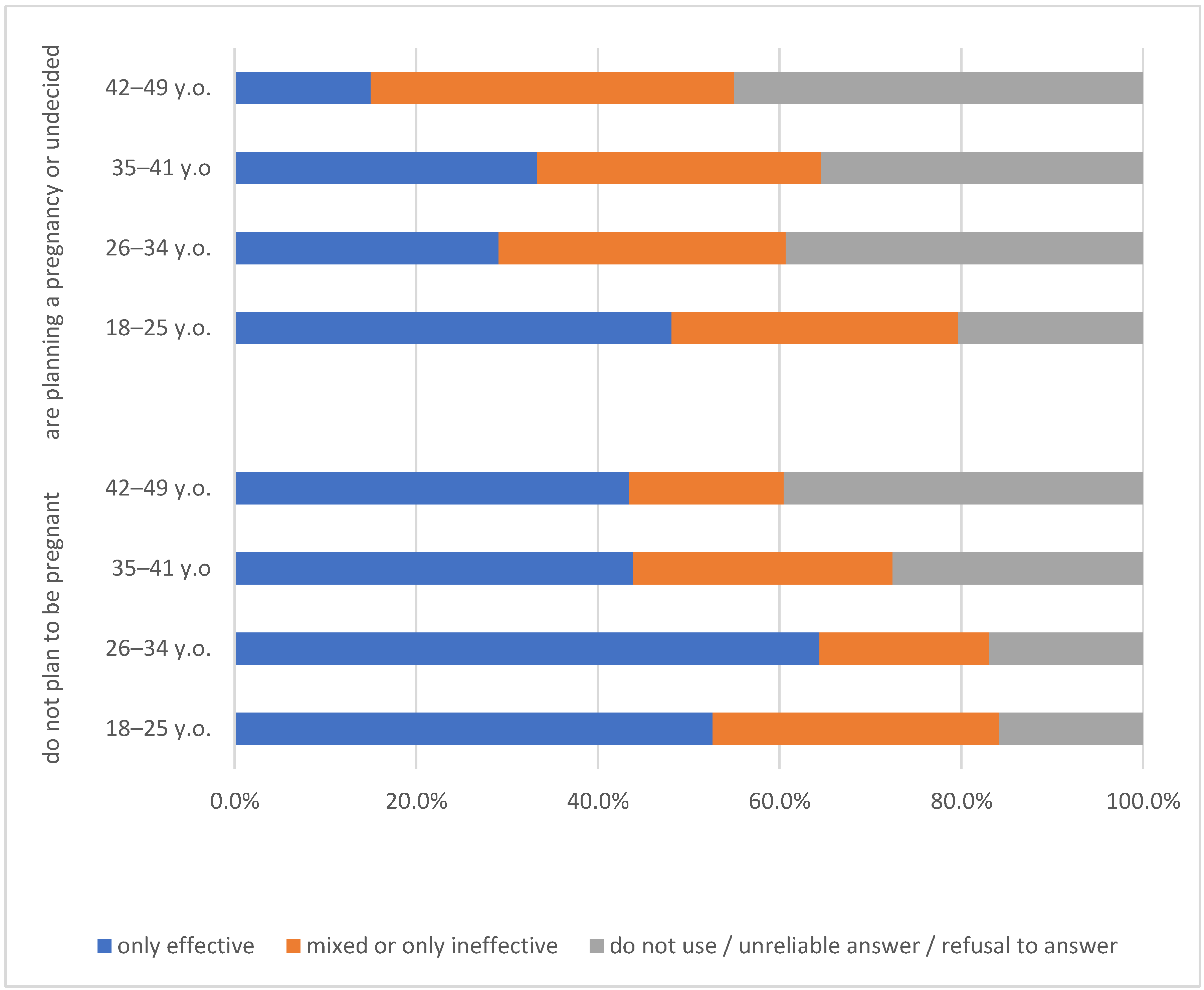

| Procreation plans | ||

| yes, soon (up to 2 years) | 122 | 19.0 |

| yes, I want to have kids, but later | 108 | 16.8 |

| no plans to have children | 305 | 47.5 |

| she did not decide | 88 | 13.7 |

| refusal to answer | 19 | 3.0 |

| Access to contraception within the last 2–3 months | ||

| had difficulties | 64 | 10.0 |

| had not any difficulties | 285 | 44.4 |

| did not need | 284 | 44.2 |

| refusal to answer | 9 | 1.4 |

| Contraceptive Methods | N * | % from the Whole Sample (N = 640) | % among Users (N = 448) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ineffective (low effectiveness) | intermittent intercourse | 136 | 21.3 | 30.4 |

| calendar method or other natural family planning method | 56 | 8.8 | 12.5 | |

| globule/gel/ spermicidal foam | 8 | 1.3 | 1.8 | |

| Effective (high effectiveness) | condom | 283 | 44.2 | 63.2 |

| contraceptive pills | 141 | 22.0 | 31.5 | |

| intrauterine device | 27 | 4.2 | 6.0 | |

| emergency contraception | 7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | |

| patches | 6 | 0.9 | 1.3 | |

| vaginal ring | 5 | 0.8 | 1.1 | |

| hormonal injections | 4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | |

| other | 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Methods Usage * | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Model of Contraception | Ineffective Model of Contraception | Lack of Contraception or No Data | ||

| In general | 42.2% | 26.8% | 31.0% | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 years old (y.o.) | 48.4% | 31.0% | 20.6% | Chi.sq = 14.54 |

| 26–34 y.o. | 40.7% | 26.3% | 33.0% | d.f. = 6 |

| 35–41 y.o. | 40.4% | 29.1% | 30.5% | p = 0.024 |

| 42–49 y.o. | 39.6% | 20.8% | 39.6% | |

| Education level | ||||

| under vocational | 36.4% | 27.2% | 36.4% | Chi.sq = 49.08 |

| vocational | 33.6% | 20.7% | 45.7% | d.f. = 6 |

| secondary | 44.8% | 34.4% | 20.8% | p < 0.001 |

| higher | 56.1% | 25.0% | 18.9% | |

| Place of residence | Chi.sq = 9.49 | |||

| country | 38.7% | 24.3% | 37.0% | d.f. = 1 |

| city | 45.3% | 29.0% | 25.7% | p = 0.008 |

| Attitude towards faith | ||||

| believers who practice regularly | 45.3% | 25.5% | 29.2% | |

| believers who practice irregularly | 36.6% | 33.3% | 30.1% | Chi.sq = 19.18 |

| non-practicing believers | 39.0% | 23.7% | 37.3% | d.f. = 8 |

| unbelievers | 59.0% | 23.1% | 17.9% | p = 0.014 |

| not specified or refusal to answer | 45.5% | 25.0% | 29.5% | |

| Economic status | ||||

| very bad | 20.5% | 30.8% | 48.7% | Chi.sq = 16.27 |

| relative or average | 40.2% | 26.4% | 33.4% | d.f. = 6 |

| good or very good | 49.8% | 26.5% | 23.7% | p = 0.012 |

| refusal to answer | 41.2% | 29.4% | 29.4% | |

| Occupation status | ||||

| professional works | 44.7% | 26.2% | 29.1% | |

| learns | 44.4% | 42.3% | 13.3% | Chi.sq = 17.72 |

| runs the house | 41.4% | 26.1% | 32.5% | d.f. = 8 |

| a pension or not working | 36.0% | 24.7% | 39.3% | p = 0.023 |

| refusal to answer | 27.8% | 16.6% | 55.6% | |

| Relationship status | ||||

| formal | 42.6% | 25.9% | 31.5% | Chi.sq = 4.41 |

| informal | 39.5% | 28.9% | 31.6% | d.f. = 6 |

| out of the relationship | 52.3% | 22.7% | 25.0% | p = 0.622 |

| refusal to answer | 62.5% | 12.5% | 25.0% | |

| The number of sexual partners in a lifetime | ||||

| one | 47.8% | 31.2% | 21.0% | Chi.sq = 17.47 |

| 2–3 | 41.2% | 25.2% | 33.6% | d.f. = 6 |

| 4 or more | 41.5% | 28.5% | 30.0% | p = 0.008 |

| no data | 34.7% | 14.3% | 51.0% | |

| Chlidren | Chi.sq = 3.87 | |||

| any | 39.1% | 32.5% | 28.4% | d.f. = 2 |

| no | 43.3% | 24.8% | 31.9% | p = 0.144 |

| Procreation plans | ||||

| yes, soon (up to 2 years) | 26.2% | 29.5% | 44.3% | |

| yes i want to have kids but later | 45.4% | 36.1% | 18.5% | Chi.sq = 32.55 |

| no plans to have children | 48.2% | 22.0% | 29.8% | d.f. = 8 |

| she did not decide | 40.9% | 30.7% | 28.4% | p < 0.001 |

| refusal to answer | 36.8% | 15.8% | 47.4% | |

| Access to contraception within the last 2–3 months | ||||

| had difficulties | 60.9% | 31.3% | 7.8% | Chi.sq = 229.21 |

| had not any difficulties | 66.3% | 25.6% | 8.1% | d.f. = 6 |

| did not need | 14.4% | 27.5% | 58.1% | p < 0.001 |

| refusal to answer | 22.2% | 11.1% | 66.7% | |

| Model: Only Effective Model of Contraception | Model: Only Ineffective Model of Contraception | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | AOR | 95% CI(AOR) | p | AOR | 95% CI(AOR) | |||

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–25 years old (y.o.) | 0.000 | 12.97 | 4.42 | 38.07 | 0.003 | 4.62 | 1.68 | 12.76 |

| 26–34 y.o. | 0.033 | 2.48 | 1.08 | 5.71 | 0.096 | 2.00 | 0.88 | 4.54 |

| 35–41 y.o. | 0.080 | 1.97 | 0.92 | 4.21 | 0.034 | 2.22 | 1.06 | 4.62 |

| 42–49 y.o. (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| under vocational | 0.037 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.94 | 0.257 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 1.51 |

| vocational | 0.002 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.64 | 0.028 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.91 |

| secondary | 0.421 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 1.62 | 0.844 | 1.08 | 0.50 | 2.36 |

| higher (fer.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Place of residence | ||||||||

| country | 0.355 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 1.34 | 0.092 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.08 |

| city (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Economic status | ||||||||

| very bad | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.098 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 1.18 |

| relative or average | 0.052 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.01 | 0.292 | 0.74 | 0.42 | 1.30 |

| good or very good (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Children | ||||||||

| no | 0.022 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.543 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 1.63 |

| any (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Attitude towards faith | ||||||||

| believers who practice regularly | 0.087 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 1.14 | 0.455 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 1.89 |

| believers who practice irregularly | 0.060 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 1.04 | 0.914 | 0.95 | 0.37 | 2.42 |

| non-practicing believers | 0.017 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.82 | 0.140 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 1.25 |

| unbelievers (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Procreation plans | ||||||||

| yes, soon (up to 2 years) | 0.000 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.037 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| yes, I want to have kids but later | 0.134 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 1.27 | 0.782 | 1.14 | 0.44 | 2.99 |

| did not decide | 0.399 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 1.61 | 0.401 | 1.40 | 0.64 | 3.06 |

| no plans to have children (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Access to contraception | ||||||||

| did not need | 0.000 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.000 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| had difficulties | 0.719 | 1.25 | 0.37 | 4.25 | 0.442 | 1.63 | 0.47 | 5.67 |

| had not any difficulties (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izdebski, Z.; Wąż, K.; Warzecha, D.; Mazur, J.; Wielgoś, M. Factors Associated with Uptake of Effective and Ineffective Contraceptives among Polish Women during the First Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912748

Izdebski Z, Wąż K, Warzecha D, Mazur J, Wielgoś M. Factors Associated with Uptake of Effective and Ineffective Contraceptives among Polish Women during the First Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912748

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzdebski, Zbigniew, Krzysztof Wąż, Damian Warzecha, Joanna Mazur, and Mirosław Wielgoś. 2022. "Factors Associated with Uptake of Effective and Ineffective Contraceptives among Polish Women during the First Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912748

APA StyleIzdebski, Z., Wąż, K., Warzecha, D., Mazur, J., & Wielgoś, M. (2022). Factors Associated with Uptake of Effective and Ineffective Contraceptives among Polish Women during the First Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912748