The Negative Effects of Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labels on Consumers’ Food Brand Evaluation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Regulatory Focus Theory

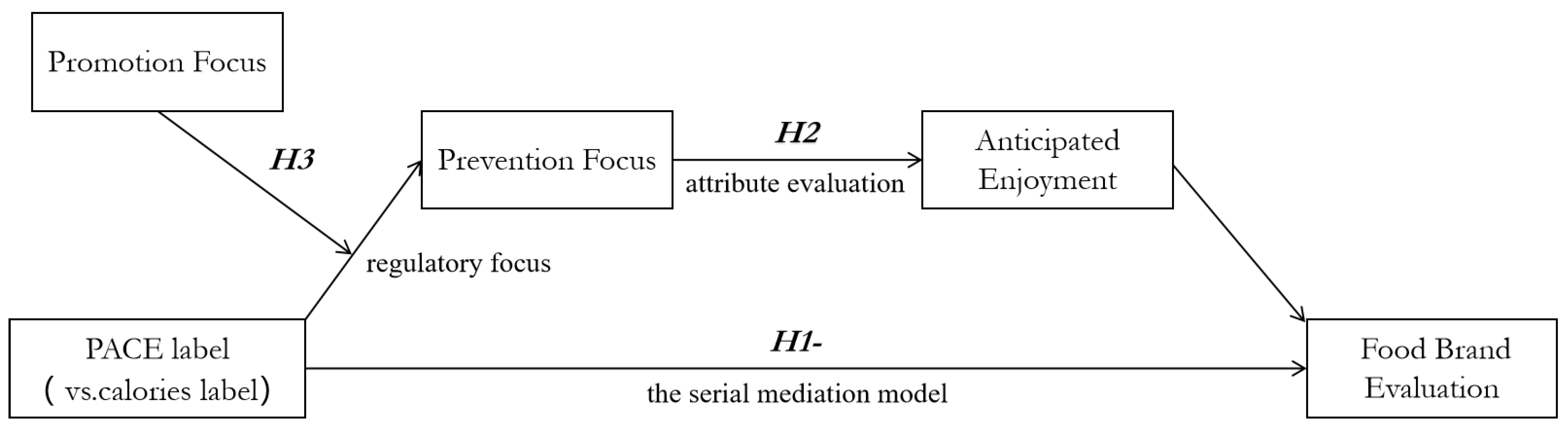

2.2. The Effects of PACE Labels on Food Brand Evaluation

2.3. Serial Mediation Model Involving Prevention Focus and Anticipated Enjoyment

2.4. Moderator Boundary of Promotion Focus

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study 1: Primary Examination of Main and Mediating Effects

3.1.1. Methodology

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

3.1.3. Results

3.2. Study 2: Examination of Moderation Effects

3.2.1. Methodology

3.2.2. Procedure and Materials

3.2.3. Results

4. General Discussion

4.1. Practical Implication

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bui, M.; Krishen, A.S. So close yet so far away: The moderating effect of regulatory focus orientation on health behavioral intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.T.; Rigby, N.; Leach, R.; Force, I.O.T. The obesity epidemic, metabolic syndrome and future prevention strategies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2004, 11, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, L.; De Smet, S.; Yusof, M.; Rajasekharan, S. Association between overweight/obesity and periodontal disease in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S. Sustainable food consumption behaviors: Incentives and intervention strategies. World Agric. 2020, 06, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieden, T.R.; Dietz, W.; Collins, J. Reducing childhood obesity through policy change: Acting now to prevent obesity. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Swinburn, B.; Lawrence, M. Obesity Policy Action framework and analysis grids for a comprehensive policy approach to reducing obesity. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagni, I.; Prevot, F.; Castro, Z.; Goubel, B.; Perrin, L.; Oppert, J.-M.; Fontvieille, A.-M. Using positive nudge to promote healthy eating at worksite: A food labeling intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, e260–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Crum, A.J. Smart food policy for healthy food labeling: Leading with taste, not healthiness, to shift consumption and enjoyment of healthy foods. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Proposes Draft Menu and Vending Machine Labeling Requirements; United States Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Brownell, K.D.; Koplan, J.P. Front-of-package nutrition labeling—An abuse of trust by the food industry? N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2373–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamlin, R.P.; McNeill, L.S.; Moore, V. The impact of front-of-pack nutrition labels on consumer product evaluation and choice: An experimental study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersey, J.C.; Wohlgenant, K.C.; Arsenault, J.E.; Kosa, K.M.; Muth, M.K. Effects of front-of-package and shelf nutrition labeling systems on consumers. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Temple, N.J.; Fraser, J. Food labels: A critical assessment. Nutrition 2014, 30, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Li, Y.A.; Li, D.; Zheng, J. The effects of physical activity calorie equivalent labeling on dieters’ food consumption and post-consumption physical activity. J. Consum. Aff. 2020, 54, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, A.J.; Bleich, S.N. Should physical activity calorie equivalent (PACE) labelling be introduced on food labels and menus to reduce excessive calorie consumption? Issues and opportunities. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Smith, J.; Jones, A. The effect of calorie and physical activity equivalent labelling of alcoholic drinks on drinking intentions in participants of higher and lower socioeconomic position: An experimental study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, Q. The Negative Effects of Long Time Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labeling on Purchase Intention for Unhealthy Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Duff, B.R.; Wang, Z.; White, T.B. Putting the organic label in context: Examining the interactions between the organic label, product type, and retail outlet. Food Qual. Preference 2016, 49, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, E.S.-T. Impact of multiple perceived value on consumers’ brand preference and purchase intention: A case of snack foods. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2010, 16, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, S.; Majeed, S. Brand purchase intention and brand purchase behavior in halal meat brand. J. Mark. 2018, 152, 152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kar, A. Green information quality and green brand evaluation: The moderating effects of eco-label credibility and consumer knowledge. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2037–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S. The influence of visual packaging design on perceived food product quality, value, and brand preference. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mookerjee, S.; Cornil, Y.; Hoegg, J.A. From waste to taste: How “ugly” labels can increase purchase of unattractive produce. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.C.; Finkel, E.J. Motivations for Promotion and Prevention and the Role of Trust and Commitment in Interpersonal Forgiveness. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.E. Taste and flavour: Their importance in food choice and acceptance. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1998, 57, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oertig, D.; SchÜler, J.; Schnelle, J.; Br Stätter, V.; Roskes, M.; Elliot, A.J. Avoidance Goal Pursuit Depletes Self-regulatory Resources. J. Personal. 2013, 81, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higgins, E.T.; Friedman, R.S.; Harlow, R.E.; Idson, L.C.; Ayduk, O.N.; Taylor, A. Achievement Orientations from Subjective Histories of Success: Promotion Pride versus Prevention Pride. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerlander, N.; Burger, D.; Fust, A.; Fueglistaller, U. Exploration and Exploitation in Established Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: The Effect of CEOs‘ Regulatory Focus. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Yue, G. New development in the domain of motivation: Regulatory focus theory. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 17, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Cornwell, J.F.; Higgins, E.T. Repeating the Past: Prevention Focus Motivates Repetition, Even for Unethical Decisions. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Lee, A.Y. The Role of Regulatory Focus in Preference Construction. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, F.; Wang, Y. Regulatory foucus in consumer bahavior research. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, J.; Higgins, E.T.; Bianco, A.T. Speed/Accuracy Decisions in Task Performance: Built-in Trade-off or Separate Strategic Concerns? Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2003, 90, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, E.Y.; Fiss, P.C. Framing Controversial Actions: Regulatory Focus, Source Credibility, and Stock Market Reaction to Poison Pill Adoption. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1734–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, E.T. Making a Good Decision: Value from Fit. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molden, D.C.; Lee, A.Y.; Higgins, E.T. Motivations for Promotion and Prevention. In Handbook of Motivation Science; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Pham, M.T. Promotion and Prevention across Mental Accounts: When Financial Products Dictate Consumers and Investment Goals. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangari, A.H.; Bui, M.; Haws, K.L.; Liu, P.J. That’s not so bad, I’ll eat more! Backfire effects of calories-per-serving information on snack consumption. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Fan, L.; Yao, Y. Health goal priming decreases high-calorie food consumption. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2018, 50, 840–847. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.D.; Gilbert, D.T. Affective Forecasting. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 35, 345–411. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.D.; Gilbert, D.T. The impact bias is alive and well. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elder, R.S.; Mohr, G.S. Guilty displeasures: How imagined guilt dampens consumer enjoyment. Appetite 2020, 150, 104641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.; Schifferstein, H.N. Sources of positive and negative emotions in food experience. Appetite 2008, 50, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macht, M.; Dettmer, D. Everyday mood and emotions after eating a chocolate bar or an apple. Appetite 2006, 46, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, S.; Williams, P. Immediate and delayed emotional consequences of indulgence: The moderating influence of personality type on mixed emotions. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tangney, J.P.; Miller, R.S.; Flicker, L.; Barlow, D.H. Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.J.; Konrath, S. “I can almost taste it”: Why people with strong positive emotions experience higher levels of food craving, salivation and eating intentions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, M.; Gao, L.; Li, T. The influence of scene on consumer word-of-mouth evaluation: Based on regulatory focus theory. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2021, 24, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, E.W.; Hong, J.; Sternthal, B. The Effect of Regulatory Orientation and Decision Strategy on Brand Judgments. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 35, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K. Taste recognition: Food for thought. Neuron 2005, 48, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savary, J.; Goldsmith, K.; Dhar, R. Giving against the odds: When tempting alternatives increase willingness to donate. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnett, A.; Spence, C. Assessing the effect of changing a bottled beer label on taste ratings. Nutr. Food Technol. Open Access 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Q. Less Is Better: How Nutrition and Low-Carbon Labels Jointly Backfire on the Evaluation of Food Products. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, R.G.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Hall, R.J. Self-Regulation at Work. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bi, X.; Li, X. Relationship among Goal Orientation, Performance Appraisal and Innovative Behavior. Manag. Admin. 2016, (02)., 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ng, T.W.H.; Lam, S.S. Promotion- and Prevention-Focused Coping: A Meta-Analytic Examination of Regulatory Strategies in the Work Stress Process. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1296–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, P.W.; Fischbach, A. A Meta-Analysis on Promotion- and Prevention-Focused Job Crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R.; Murray, K.B.; Cotte, J. Beyond Expectations: The Effect of Regulatory Focus on Consumer Satisfaction. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Houston, M.B.; Yoo, B. Social Dollars in Online Communities: The Effect of Product, User, and Network Characteristics. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowe, E.; Higgins, T.E. Regulatory Focus and Strategic Inclinations: Promotion and Prevention in Decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1997, 69, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gneezy, A. Field experimentation in marketing research. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.G. Theory and external validity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cvelbar, L.K.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. Which hotel guest segments reuse towels? Selling sustainable tourism services through target marketing. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, N.M.; Fang, Z.; Luo, X. Geo-conquesting: Competitive locational targeting of mobile promotions. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winterich, K.P.; Nenkov, G.Y.; Gonzales, G.E. Knowing what it makes: How product transformation salience increases recycling. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Dahl, D.W.; Hoeffler, S. Optimal visualization aids and temporal framing for new products. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Sengupta, J. The influence of disease cues on preference for typical versus atypical products. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, P.J.; Klesse, A.-K. Making recommendations more effective through framings: Impacts of user-versus item-based framings on recommendation click-throughs. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, P.; Torelli, C.J. It’s not just numbers: Cultural identities influence how nutrition information influences the valuation of foods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, G.E.; Gorlin, M.; Dhar, R. When going green backfires: How firm intentions shape the evaluation of socially beneficial product enhancements. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J. Analogying with Memory or Simulating the Results? ——The Matching Effect of Learning Strategy and Regulatory Focus on Consumers’ Intelligent Hardware Adoption. Collect. Essays Finance Econ. 2020, 09, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, S.A.; Fitzsimons, G.J.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; McClelland, G.H. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tobi, R.C.; Harris, F.; Rana, R.; Brown, K.A.; Quaife, M.; Green, R. Sustainable diet dimensions. Comparing consumer preference for nutrition, environmental and social responsibility food labelling: A systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/changes-nutrition-facts-label (accessed on 7 March 2022).

| Study | Hypothesis | Grouping | Major Variables | Stimulant | Control Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H1 | Intergroups: label (PACE vs. calories) | Purchase intention, brand evaluation, regulatory focus, anticipated enjoyment | chickpea | Demographic |

| 2 | H2 | Intergroup: 2 labels (PACE vs. calories) × 2 focus (promotion vs. control) | chocolate | Involvement in food choices |

| Socio-Demographic Indicators | Study 1 | Study 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Definitions | Percentage | Percentage |

| Gender | Male | 45.1% | 36.9% |

| Female | 54.9% | 63.1% | |

| Age | ≤20 years old | 11.1% | 8.9% |

| 21–30 years old | 71.1% | 52.5% | |

| 31–40 years old | 13.2% | 28.3% | |

| ≥41 years old | 4.6% | 10.3% | |

| Education | Senior high school and below | 2.0% | 5.8% |

| junior college | 7.5% | 16.7% | |

| bachelor’s degree | 67.8% | 65.6% | |

| post-graduate degree and above | 22.7% | 11.9% | |

| Disposable income | 2000 yuan and below | 31.9% | 18.6% |

| 2001–4000 yuan | 24.7% | 26.4% | |

| 4001–6000 yuan | 15.1% | 21.7% | |

| 6001 yuan and above | 28.3% | 33.3% | |

| Valid sample size | 304 | 360 | |

| Variable | Definitions | PACE Group | Calories Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase intention | Mean (standard deviation) | 3.66(1.455) | 4.51(1.327) |

| F | 27.988 *** | ||

| partial η2 | 0.085 | ||

| 1-β | 1.000 | ||

| Food brand evaluation | Mean (standard deviation) | 4.01(1.400) | 4.61(1.189) |

| F | 27.327 *** | ||

| partial η2 | 0.051 | ||

| 1-β | 0.980 | ||

| Prevention focus | Mean (standard deviation) | 5.13(0.947) | 4.43(1.250) |

| F | 29.787 *** | ||

| partial η2 | 0.090 | ||

| 1-β | 1.000 | ||

| Anticipated enjoyment | Mean (standard deviation) | 4.18(1.458) | 5.10(1.115) |

| F | 38.650 *** | ||

| partial η2 | 0.113 | ||

| 1-β | 1.000 | ||

| Variable | Definitions | Control | Promotion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PACE Group | Calories Group | PACE Group | Calories Group | ||

| Manipulation check | Mean (standard deviation) | 5.18(1.196) | 5.98(0.620) | ||

| partial η2 | 0.151 | ||||

| 1-β | 1.000 | ||||

| Purchase intention | Mean (standard deviation) | 4.40(1.490) | 5.26(1.230) | 4.58(1.388) | 5.36(1.281) |

| F | 18.098 *** | 14.987 *** | |||

| Food brand evaluation | Mean (standard deviation) | 4.55(1.241) | 5.21(0.945) | 5.15(1.131) | 5.36(1.017) |

| F | 16.313 *** | 1.692 | |||

| Prevention focus | Mean (standard deviation) | 5.14(1.108) | 4.11(1.601) | 4.12(1.637) | 4.10(1.580) |

| F | 25.271 *** | 0.009 | |||

| Anticipated enjoyment | Mean (standard deviation) | 4.84(1.526) | 5.63(1.063) | 5.48(1.103) | 5.75(0.939) |

| F | 16.610 *** | 3.256 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Hong, M.; Shi, D.; Chen, Q. The Negative Effects of Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labels on Consumers’ Food Brand Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912676

Yang X, Hong M, Shi D, Chen Q. The Negative Effects of Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labels on Consumers’ Food Brand Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912676

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaoke, Meiling Hong, Dejin Shi, and Qian Chen. 2022. "The Negative Effects of Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labels on Consumers’ Food Brand Evaluation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912676

APA StyleYang, X., Hong, M., Shi, D., & Chen, Q. (2022). The Negative Effects of Physical Activity Calorie Equivalent Labels on Consumers’ Food Brand Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912676