Nudging Strategies for Arable Land Protection Behavior in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

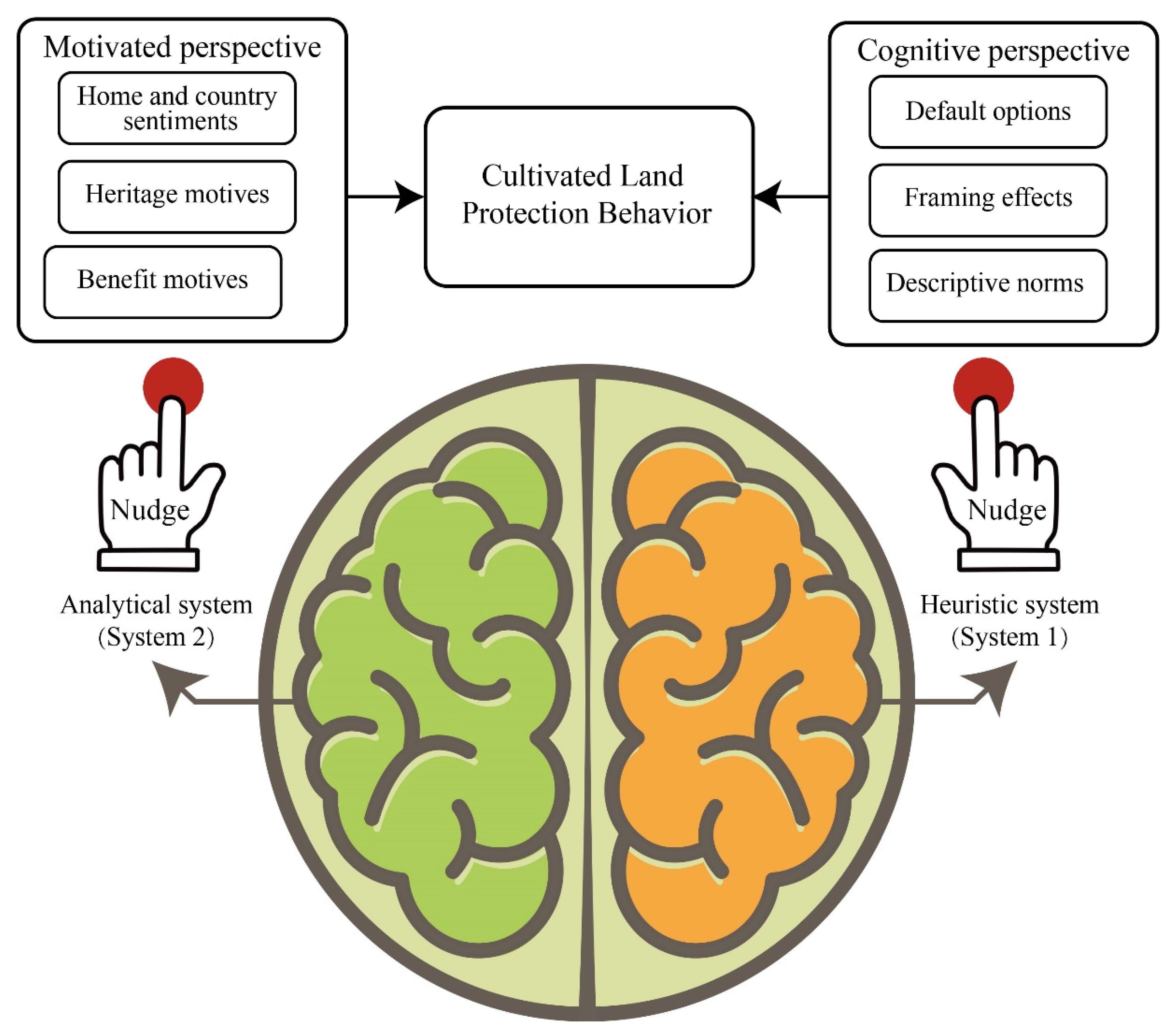

2. Nudge Theory

2.1. What Is Nudge?

2.2. Why Do We Need Nudge for Arable Land Protection Behavior?

3. Cognitive Perspective of the Nudging Strategies of Arable Land Protection Behavior

3.1. Default Options Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

3.2. Framing Effects Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

3.3. Descriptive Norms Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

4. Motivated Perspective of the Nudging Strategies of Arable Land Protection Behavior

4.1. Home and Country Sentiments Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

4.2. Heritage Motives Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

4.3. Benefit Motives Nudge Arable Land Protection Behavior

5. Discussion: Controversies That May Exist in the Practice of Nudge in Arable Land Protection Behavior

5.1. Nudge May Be Evil?

5.2. Nudge Leads to Childization?

5.3. Can Nudge Be Effective in the Long Term?

6. Policy Implications: Effective Use of Nudge to Promote Arable Land Protection Behavior in China

6.1. Selection of Nudging Strategies Based on the Subdivision of Farmer Groups

6.2. Number of Options for the Nudging Strategies Should Be Appropriate

6.3. Clarification of the External Environment That Nudges the Arable Land Protection Behavior

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Arable land protection and rational use in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hao, H.; Hu, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Livelihood Diversification of Farm Households and Its Impact on Arable Land Utilization in Agro-pastoral Ecologically-vulnerable Areas in the Northern China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Ji, Y.; Xu, H.; Qiu, H.; Sun, L.; Zhong, H.; Liu, J. The potential contribution of growing rapeseed in winter fallow fields across Yangtze River Basin to energy and food security in China. Resources. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y. Measuring urbanization-occupation and internal conversion of peri-urban arable land to determine changes in the peri-urban agriculture of the black soil region. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, M.; Xia, C. Impact of urbanization on the eco-efficiency of arable land utilization: A case study on the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, J. A multi-faceted, location-specific assessment of land degradation threats to peri-urban agriculture at a traditional grain base in northeastern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, M. Land degradation sensitivity assessment and convergence analysis in Korla of Xinjiang, China. J. Arid. Land 2020, 12, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, H.; Xin, L.; Tan, M. How reliable are arable land assets as social security for Chinese farmers? Land Use Policy 2019, 90, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Evolutionary game and simulation of management strategies of fallow arable land: A case study in Hunan province, China. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Jin, S. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Fallow Farmland Behaviors of Different Types of Farmers and Local governments. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yu, C.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Farmer differentiation, generational differences and farmers’ behaviors to withdraw from rural homesteads: Evidence from chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Scott, S.; Wang, K. The effects of basic arable land protection planning in Fuyang County, Zhejiang Province, China. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 422–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.; Han, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X. Quantitative evaluation of China’s arable land protection policies based on the PMC-Index model. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Performance Evaluation Model of Economic Compensation Policy for Arable Land Protection in Coastal Areas Based on Propensity Value Matching Method. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wen, J.; Choi, Y. How the SDGs are implemented in China-A comparative study based on the perspective of policy instruments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Dynamic trends and driving forces of land use intensification of arable land in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, T.; Daly, M.; Heffernan, E.; Reynolds, N. The carrot and the stick: Policy pathways to an environmentally sustainable rental housing sector. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Estimating the environmental effects and recreational benefits of arable flower land for environmental quality improvement in Taiwan. Agric. Econ. 2016, 48, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Robinson, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Tong, L. Factors Influencing Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in the Conversion of Arable Land to Wetland Program in Sanjiang National Nature Reserve, China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mols, F.; Haslam, S.A.; Jetten, J.; Steffens, N.K. Why a nudge is not enough: A social identity critique of governance by stealth. Eur. J. Political Res. 2015, 54, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Bosco, L.; Stabile, A. Nudging pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from a web experiment on priming and WTP. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 63, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, B.; Sudzina, F.; Ornbo, L.; Tvedebrink, T. Does visibility matter?-A simple nudge reduces the purchase of sugar sweetened beverages in canteen drink coolers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 92, 104190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kameke, C.; Fischer, D. Preventing household food waste via nudging: An exploration of consumer perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, A.; Barnes, C.; Lum, M.; Jones, J.; Yoong, S. Impact of Nudge Strategies on Nutrition Education Participation in Child Care: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hu, L.; Zheng, W.; Yao, S.; Qian, L. Impact of household land endowment and environmental cognition on the willingness to implement straw incorporation in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.; Wilson, C.; Bell, M. The role of private corporations in regional planning and development: Opportunities and challenges for the governance of housing and land use. J. Rural. Stud. 2012, 28, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskind, P. “Enlightened System” or “Regulatory Nightmare”?: New York’s Adirondack Mountains and the Conflicted Politics of Environmental Land-Use Reform During the 1970s. J. Policy Hist. 2019, 31, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Nudge, not sludge. Science 2018, 361, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C.; Balz, J. Choice architecture. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, G. Market adoption simulation of electric vehicle based on social network model considering nudge policies. Energy 2022, 259, 124984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Nudging for Social Change: Promises and Cautions for Social Workers to Apply Behavioural Economic Tools. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, bcac153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, M.; Ye, W.; Zhang, B. Assessing the impact of green nudges on ozone concentration: Evidence from China’s night refueling policy. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duflo, E.; Kremer, M.; Robinson, J. Nudging Farmers to Use Fertilizer: Theory and Experimental Evidence from Kenya. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 2350–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, D.; Welch, B. Debate: To Nudge or Not to Nudge. J. Political Philos. 2010, 18, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwig, R.; Grune-Yanoff, T. Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Good Decisions. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniw, J.; Sa, J.; Lal, R.; Ferreira, A.; Inagaki, T.; Briedis, C.; Goncalves, D.; Canalli, L.; Padilha, A.; Bressan, P. C-offset and crop energy efficiency increase due industrial poultry waste use in long-term no-till soil minimizing environmental pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jin, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of influencing factors of arable land fragmentation based on hierarchical linear model: A case study of Jiangsu Province, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Cao, J.; Degen, A.; Zhang, D.; Long, R. A four year study in a desert land area on the effect of irrigated, arable land and abandoned cropland on soil biological, chemical and physical properties. Catena 2019, 175, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belayneh, M.; Yirgu, T.; Tsegaye, D. Runoff and soil loss responses of arable land managed with graded soil bunds of different ages in the Upper Blue Nile basin, Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Stanovich, K. Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, T.; Hao, J. The evolving concepts of land administration in China: Arable land protection perspective. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H. Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Wang, L.; Qin, J.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Y. Evaluating arable land stability during the growing season based on precipitation in the Horqin Sandy Land, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Fu, R.; Liu, H.; Guo, X. Current knowledge from heavy metal pollution in Chinese smelter contaminated soils, health risk implications and associated remediation progress in recent decades: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Guo, R.; Hong, W. Institutional transition and implementation path for arable land protection in highly urbanized regions: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, W.; Huang, L.; Du, H. Exploring the Effectiveness of Multifunctional Arable Land Protection Linking Supply to Demand in Value Engineering Theory: Evidence from Wuhan Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Song, M. Ecological Benefit Spillover and Ecological Financial Transfer of Arable Land Protection in River Basins: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Wang, M.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, D.; Ma, W. Towards arable land multifunction assessment in China: Applying the “influencing factors-functions-products-demands” integrated framework. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, J.; Heimann, M.; Meunier, L. Nudges in SRI: The Power of the Default Option. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 177, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Pykett, J.; Whitehead, M. The geographies of policy translation: How nudge became the default policy option. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Hallsworth, M.; Halpern, D.; King, D.; Metcalfe, R.; Vlaev, I. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Salustri, F.; Scaramozzino, P. Nudging and corporate environmental responsibility: A natural field experiment. Food Policy 2020, 97, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderer, L.; Kjaer, M.; Madsen, E.; Busch, J.; Fage-Butler, A. Nudging in Public Health Lifestyle Interventions: A Systematic Literature Review and Metasynthesis. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Yue, W. Urban land expansion and regional inequality in transitional China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 163, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Ye, X. Urbanization, urban land expansion and environmental change in China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N.; Zhang, W. Harnessing the Forces of Urban Expansion: The Public Economics of Farmland Development Allowances. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shan, J.; Choguill, C. Combining behavioral interventions with market forces in the implementation of land use planning in China: A theoretical framework embedded with nudge. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inesi, M. Power and loss aversion. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 112, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, A.; Fleming, S.M.; Bach, D.R.; Driver, J.; Dolan, R.J. A Regret-Induced Status Quo Bias. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 3320–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J. Evaluating framing effects. J. Econ. Psychol. 2001, 22, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F. Frames of mind in intertemporal choice. Manag. Sci. 1988, 34, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, W.; Soypak, K. Framing effects in intertemporal choice tasks and financial implications. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 51, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; He, X.; De Falcis, E. What Drives China’s New Agricultural Subsidies? World Dev. 2017, 93, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Carter, P.; Blair, E. Attribute framing and goal framing effects in health decisions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 85, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; He, R.; Wang, W.; Gong, H. Valuing arable land protection: A contingent valuation and choice experiment study in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. Utilization benefit of arable land and land institution reforms: Economy, society and ecology. Habitat Int. 2017, 77, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R. Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control. Psychometrika 2007, 72, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R.; Lu, Q.; Aziz, N. Does the stability of farmland rental contract & conservation tillage adoption improve family welfare? Empirical insights from Zhangye, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105486. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, J.; Gao, S.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Vinay, N.; Mo, F.; Liao, Y.; Wen, X. Conservation tillage enhances crop productivity and decreases soil nitrogen losses in a rainfed agroecosystem of the Loess Plateau, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Siddique, K.; Li, F. Adoption of Conservation Tillage on the Semi-Arid Loess Plateau of Northwest China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N. What gave rise to China’s land finance? Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, J.R., III. Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects. Nature 1993, 363, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, J.R., III. Future prospects discussed. Nature 1994, 368, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Wall Slogans: The Communication of China’s Family Planning Policy in Rural Areas. Rural Hist. 2018, 29, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Han, W. Decision analysis of the elderly participating in the housing reverse mortgage: Based on bequest motivation constraint. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 40, 8569–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Rental markets for arable land and agricultural investments in China. Agric. Econ. 2012, 43, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Sun, Y. Power, capital, and the poverty of farmers’ land rights in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; MacDonald, G.; Galloway, J.; Zhang, L.; Gao, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Yang, T. The influence of crop and chemical fertilizer combinations on greenhouse gas emissions: A partial life-cycle assessment of fertilizer production and use in China. Resources. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 168, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, Y.; Du, W.; Li, C.; Xu, M.; Xie, T.; Yin, Y.; Guo, H. Response of soil bacterial communities, antibiotic residuals, and crop yields to organic fertilizer substitution in North China under wheat- maize rotation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Kassa, F.; Darun, M.; Klemes, J. Life cycle cost analysis of wastewater treatment: A systematic review of literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. The Ethics of Nudging. Yale J. Regul. 2015, 32, 413–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal-Barby, J.; Burroughs, H. Seeking Better Health Care Outcomes: The Ethics of Using the “Nudge”. Am. J. Bioeth. 2012, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Zhai, L. Land abandonment under rural restructuring in China explained from a cost-benefit perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploug, T.; Holm, S.; Brodersen, J. To nudge or not to nudge: Cancer screening programmes and the limits of libertarian paternalism. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.C.; Lun, F.; Min, Q.; Li, W. The impacts of farmers’ livelihood capitals on planting decisions: A case study of Zhagana Agriculture-Forestry-Animal Husbandry Composite System. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, C.; Leon, H.; Perez, E.; Herrero, M. Characterising objective profiles of Costa Rican dairy farmers. Agric. Syst. 2001, 67, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, Y. Study on Farmland Abandonment Behavior of Farmers from Intergenerational Differences Perspectives: Based on 293 Farmer Questionnaires in Xingguo County, Jiangxi Province. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Wang, L.; Ning, M. Farmers’ Livelihood Differentiation and Pesticide Application: Empirical Evidence from a Causal Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Lepper, M. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimcher, P. Efficiently irrational: Deciphering the riddle of human choice. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, H. Taking Decisions Too Seriously: Why Maximizers Often Get Mired in Choices. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 878552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, H.; Gao, F. Differentiation of farmers, technical constraints and the differences of cultivated land protection technology selection: A theoretical analysis framework of farmer households’ technological adoption based on different constraints. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 2956–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, Y. Influencing factors of farmers’ adoption of pro-environmental agricultural technologies in China: Meta-analysis. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, B.; Fleischhut, N.; Osman, M. Beyond the confines of choice architecture: A critical analysis. J. Econ. Psychol. 2018, 68, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, H.; Duan, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Z. Farmers’ attitudes towards the introduction of agri-environmental measures in agricultural infrastructure projects in China: Evidence from Beijing and Changsha. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zou, Y.; Lv, T. Nudging Strategies for Arable Land Protection Behavior in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912609

Zhang Y, Lu X, Zou Y, Lv T. Nudging Strategies for Arable Land Protection Behavior in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912609

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanwei, Xinhai Lu, Yucheng Zou, and Tiangui Lv. 2022. "Nudging Strategies for Arable Land Protection Behavior in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912609

APA StyleZhang, Y., Lu, X., Zou, Y., & Lv, T. (2022). Nudging Strategies for Arable Land Protection Behavior in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912609