Acculturation, Work-Related Stressors, and Respective Coping Strategies among Male Indonesian Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industry in Taiwan: A Post-COVID Investigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Relationships at Work

“I have a really good relationship with them. They are really kind to me and treat me as their children and friend. Sometimes there is a language barrier, but they would understand and explain to me patiently.”

“…regarding the relationship with my boss or the foreman, it is not very harmonious. They do not really appreciate or respect our work. And when we need anything, they do not really show any effort to help us.”

3.2. Workplace Violence

“… I was physically abused. Thus, I recorded everything that happened and reported it to 1955.”

“I had a problem with my Taiwanese supervisor to the point where we physically fought. The incident was reviewed through the CCTV (closed-circuit television) security system, and he ended up being expelled.”

“In the previous factory, the boss was physically abusive and got mad easily. That is one of the reasons I shifted to my new job.”

3.3. Language Barriers and Proficiency

“I feel my Chinese ability has not improved because I could not talk with anyone.”

“It is all good. Sometimes I become a comedian to the Taiwanese because of my Chinese ability.”

“I am already quite comfortable with the Taiwanese coworkers here because I could already understand some Chinese conversational words. I could also ask them for help if there are things I do not understand. My relationships with my boss and other coworkers are also good.”

3.4. Sick Leaves

“Since we already have insurance, if the sickness is not that severe, we would just go to the hospital by ourselves.”

“If it is still bearable, we would just hold it. Our friends would help with our work so that it is not too heavy. We will not tell the boss because they would directly bring us to the clinic, while we Indonesians do not really like going to hospitals or clinics.”

3.5. Other Stressors

“My problems are usually related to the agency. They sometimes think that I do not have any knowledge, so they trick me by asking for a lot of money to extend my passport.”

“There was one time when I wanted to move to another factory, and the agency asked me to pay around NT$24,000. I felt it was a lot of money. Since I did not want to go back to Indonesia, I had to pay.“

3.6. Activities Outside Work

“I joined social activities such as fundraising, being active in organizations, and gathered with other Indonesian friends to share our daily lives.”

“I am very grateful to the Taiwan government for providing us facilities to pray and do other religious practices before the pandemic since our factory does not have a praying facility.”

3.7. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

“We do not get any overtime work anymore, which affects our income. Meanwhile, we have to pay a lot of things aside from our living fees.”

“… it has been four years since the last time I met my wife and children.”

“I feel quite stressed because it is even harder to go out of the factory…”

“There are too many people in the dormitory, so there is a higher risk for us getting sick or COVID-19.”

“I felt happier because there was less workload, but with the same amount of salary.”

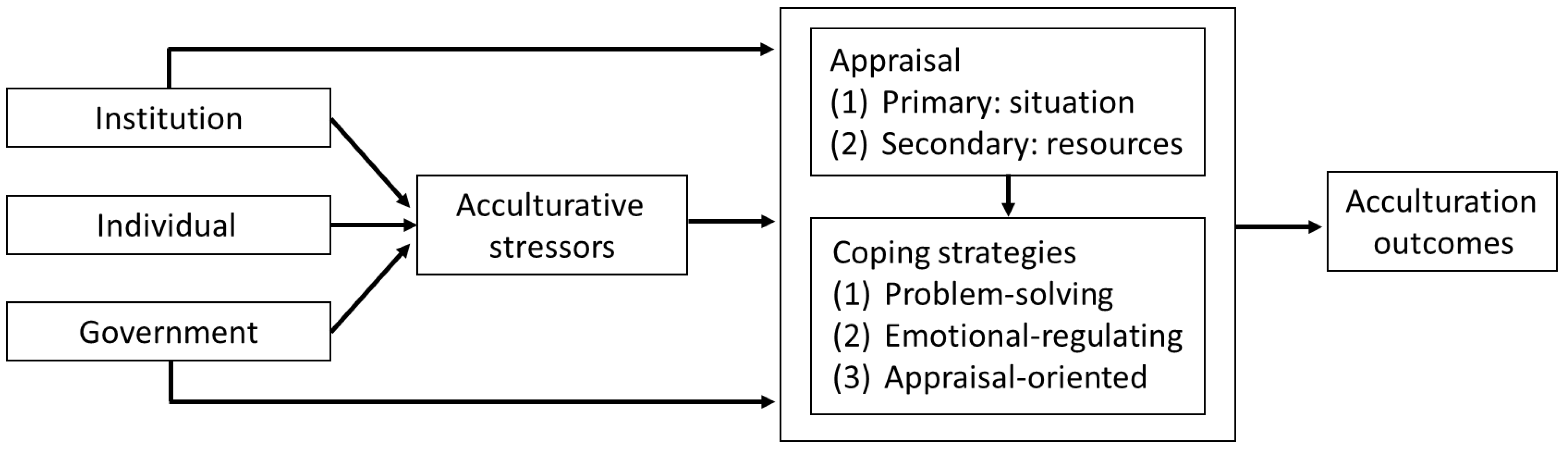

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Acculturation

4.2. Coping Strategies

4.3. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ILO. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers—Results and Methodology. International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Ministry of Labor Labor Statistics Search Website (Chinese). Available online: https://statfy.mol.gov.tw/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Hargreaves, S.; Rustage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; McAlpine, A.; Pocock, N.; Devakumar, D.; Aldridge, R.W.; Abubakar, I.; Kristensen, K.L.; Himmels, J.W.; et al. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, E872–E882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moyce, S.C.; Schenker, M. Migrant Workers and Their Occupational Health and Safety. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 2018, 39, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Flynn, M.A. Safety & the Diverse Workforce: Lessons From NIOSH’s Work With Latino Immigrants. Prof. Saf. 2014, 59, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schenker, M.B. A Global Perspective of Migration and Occupational Health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Liao, H.-C.; Cheng, S.-F.; Lee, L.-H. Occupational fatality and injury risks for overseas blue-collar workers in Taiwan. J. Chin. Inst. Ind. Eng. 2011, 28, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, A.; Ikeda, T.; Takahashi, M.; Haratani, T.; Hojou, M.; Fujioka, Y.; Swanson, N.G.; Araki, S. Impact of psychosocial job stress on non-fatal occupational injuries in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2006, 49, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, M.F.; Whiteford, H.A. Associations between psychological distress, workplace accidents, workplace failures and workplace successes. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2010, 83, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, D.L.; Berry, J.W. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, A.; Carey, R.N.; Darcey, E.; Chih, H.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Milner, A.; Reid, A. Workplace psychosocial stressors experienced by migrant workers in Australia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, H.; Miller, A.; Park, C.G.; Kim, S.J. Acculturative Stress, Work-related Psychosocial Factors and Depression in Korean-Chinese Migrant Workers in Korea. J. Occup. Health 2012, 54, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liem, A.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Hannam, K.; Lam, A.I.F.; Hall, B.J. Acculturative stress and coping among migrant workers: A global mixed-methods systematic review. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021, 13, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Free Association Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Lazarus, R.S. Personality and Adjustment; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1997, 46, 5–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Berry, J.W.; Poortinga, Y.H.; Segall, M.H.; Dasen, P.R. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hajro, A.; Stahl, G.K.; Clegg, C.C.; Lazarova, M.B. Acculturation, coping, and integration success of international skilled migrants: An integrative review and multilevel framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.W.; Wu, T.C. An investigation and analysis of major accidents involving foreign workers in Taiwan’s manufacture and construction industries. Safety Sci. 2013, 57, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.N.; Liou, S.H.; Hsu, C.C.; Chao, S.L.; Liou, S.F.; Ko, K.N.; Yeh, W.Y.; Chang, P.Y. Epidemiologic study of occupational injuries among foreign and native workers in Taiwan. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1997, 31, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, P. A Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data Coding, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Ministry of Justice Laws & Regulations Database of Taiwan. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/index.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Dembe, A.E.; Erickson, J.B.; Delbos, R.G.; Banks, S.M. The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: New evidence from the United States. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gany, F.; Dobslaw, R.; Ramirez, J.; Tonda, J.; Lobach, I.; Leng, J. Mexican Urban Occupational Health in the US: A Population at Risk. J. Commun. Health 2011, 36, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.B.; Thomas, M. Predictive factors of acculturation attitudes and social support among Asian immigrants in the USA. Int J. Soc. Welf 2009, 18, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaen, G.M.H.; van Amelsvoort, L.P.G.M.; Bultmann, U.; Slangen, J.J.M.; Kant, I.J. Psychosocial work characteristics as risk factors for being injured in an occupational accident. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Lorente, L.; Vignoli, M.; Nielsen, K.; Peiro, J.M. Challenges influencing the safety of migrant workers in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Safety. Sci. 2021, 142, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanou, D.; O’Reilly, E.; Ngnie-Teta, I.; Batal, M.; Mondain, N.; Andrew, C.; Newbold, B.K.; Bourgeault, I.L. Acculturation and nutritional health of immigrants in Canada: A scoping review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, D.S. The construction site as a multicultural workplace: A perspective of minority migrant workers in Brunei. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2009, 27, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S. Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy Polit Nurs. Pract. 2007, 8, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magana, C.G.; Hovey, J.D. Psychosocial stressors associated with Mexican migrant farmworkers in the midwest United States. J. Immigr. Health 2003, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weishaar, H.B. “You have to be flexible”-Coping among polish migrant workers in Scotland. Health Place 2010, 16, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fischer, P.; Ai, A.L.; Aydin, N.; Frey, D.; Haslam, S.A. The Relationship Between Religious Identity and Preferred Coping Strategies: An Examination of the Relative Importance of Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Coping in Muslim and Christian Faiths. Rev. Gen. Psychol 2010, 14, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C.; Wang, M.C.; Liao, H.C.; Cheng, S.F.; Wang, Y.H. Hazard Prevention Regarding Occupational Accidents Involving Blue-Collar Foreign Workers: A Perspective of Taiwanese Manpower Agencies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerin, P.J.; Vold, L.; Aavitsland, P. Communicable disease control in a migrant seasonal workers population: A case study in Norway. Euro. Surveill 2005, 10, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pithara, C.; Zembylas, M.; Theodorou, M. Access and effective use of healthcare services by temporary migrants in Cyprus. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2012, 8, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Wu, N.C.; Su, H.C.; Hsu, C.C.; Guo, H.R.; Chen, K.T. Differences in injury and trauma management between migrant workers and citizens. Medicine 2020, 99, e21553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.S.; Chan, T.C. The intersections of the care regime and the migrant care worker policy: The example of Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2017, 27, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subchi, I.; Jahar, A.S.; Rahiem, M.D.; Ni’am Sholeh, A. Negotiating Religiosity in a Secular Society: A Study of Indonesian Muslim Female Migrant Workers in Hong Kong. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2022, 30, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Barbato, M. Positive Religious Coping and Mental Health among Christians and Muslims in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 2020, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Tourism Bureau Muslim-friendly Environment. Available online: https://eng.taiwan.net.tw/m1.aspx?sNo=0020308 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Taiwan Ministry of Labor For Foreign Workers to Work in Taiwan. Available online: https://www.wda.gov.tw/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Jones, K.; Mudaliar, S.; Piper, N. Locked Down and in Limbo: The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Migrant Worker Rights and Recruitment; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hennebry, J.; Hari, K.C. Quarantined! Xenophobia and Migrant Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L.G.; Sabin, K. Sampling Hard-to-Reach Populations with Respondent Driven Sampling. Methodol. Innov. Online 2010, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positive Perceptions | Acculturative Stress |

|---|---|

|

|

| Acculturative Stressor | Level of Available Resources for Coping | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual * | Institutional | Governmental Policy | |

| Language barriers |

|

| |

| Limited food options |

|

| |

| Poor health conditions/ injury/physical abuse |

|

|

|

| Others |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, W.-C.; Chanaka, N.S.; Tsaur, C.-C.; Ho, J.-J. Acculturation, Work-Related Stressors, and Respective Coping Strategies among Male Indonesian Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industry in Taiwan: A Post-COVID Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912600

Lee W-C, Chanaka NS, Tsaur C-C, Ho J-J. Acculturation, Work-Related Stressors, and Respective Coping Strategies among Male Indonesian Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industry in Taiwan: A Post-COVID Investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912600

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Wan-Chen, Natasia Shanice Chanaka, Charng-Cheng Tsaur, and Jiune-Jye Ho. 2022. "Acculturation, Work-Related Stressors, and Respective Coping Strategies among Male Indonesian Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industry in Taiwan: A Post-COVID Investigation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912600

APA StyleLee, W.-C., Chanaka, N. S., Tsaur, C.-C., & Ho, J.-J. (2022). Acculturation, Work-Related Stressors, and Respective Coping Strategies among Male Indonesian Migrant Workers in the Manufacturing Industry in Taiwan: A Post-COVID Investigation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12600. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912600