Digital and Non-Digital Solidarity between Older Parents and Their Middle-Aged Children: Associations with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intergenerational Solidarity

2.2. Digital Solidarity in Intergenerational Relationships

2.3. Intergenerational and Digital Solidarity and Older Adults’ Mental Heath

2.4. The Current Study

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Results of Descriptive Analysis

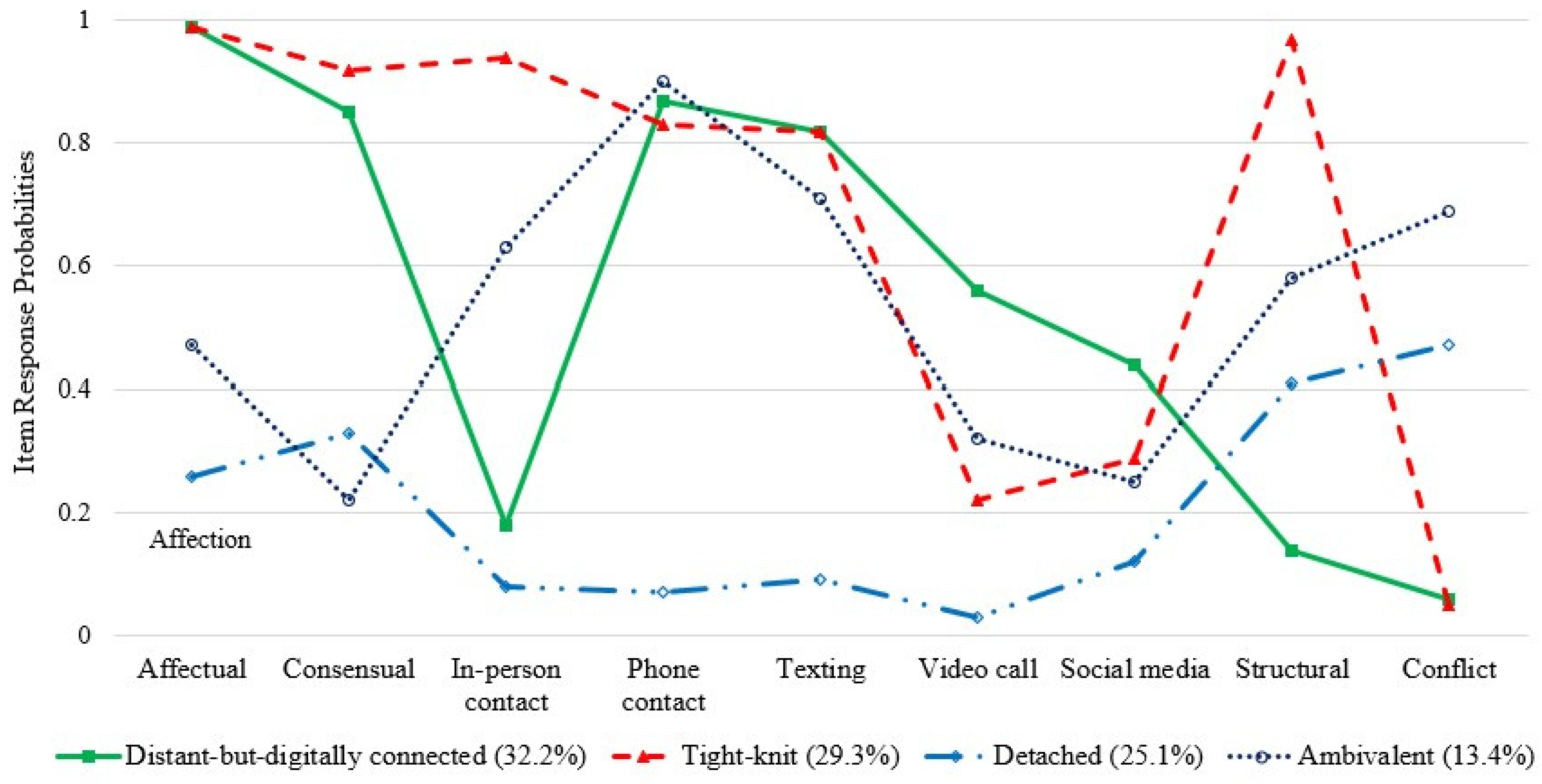

4.2. Results of Latent Class Analysis

4.3. Associations between Intergenerational Solidarity Latent Classes and Mental Health

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cudjoe, T.K.M.; Kotwal, A.A. “Social distancing” Amid a crisis in social isolation and loneliness. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, E27–E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luykx, J.J.; Vinkers, C.H.; Tijdink, J.K. Psychiatry in times of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: An imperative for psychiatrists to act now. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M.; Bordone, V.; Solé-Auró, A. Older people’s nonphysical contacts and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown. Gerontologist 2020, 61, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore WD, S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nayar, K.R. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. J. Ment. Health 2020, 30, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, P.A. Cross-national differences in intergenerational family relations: The influence of public policy Arrangements. Innov. Aging 2018, 2, igx032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, J.K.; Ali, T.; Syed, S.; Piechota, A.; Lepore, M.; Mourgues, C.; Gaugler, J.E.; Marottoli, R.; David, D. Family communication in long-term care during a pandemic: Lessons for enhancing emotional experiences. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, B.; Pasqualini, M.; Bordone, V. Physically distant but socially close? Changes in non-physical intergenerational contacts at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic among older people in France, Italy and Spain. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 18, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Qian, Y. COVID-19, Inter-household contact and mental well-being among older adults in the US and the UK. Front. Sociol. 2021, 6, 714626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerlad, A.; Marston, L.; Huntley, J.; Livingston, G.; Lewis, G.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Social relationships and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal analysis of the COVID-19 Social Study. Psychol. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.L.; Richards, L.N.; Bengtson, V. Intergenerational solidarity in families: Untangling the ties that bind. Marriage Fam. Rev. 1991, 16, 11–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Bengtson, V.L. Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child-parent relationships in American families. Am. J. Sociol. 1997, 103, 429–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, V.; Giarrusso, R.; Mabry, J.B. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, K. Intergenerational ambivalence: Further steps in theory and research. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.; Kim, J.H.; Brown, M.T.; Silverstein, M. Are filial eldercare norms related to intergenerational solidarity with older parents? A typological developmental approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, B. Affection and conflict in intergenerational relationships of women in sixteen areas in Asia, Africa, Europe, and America. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2014, 39, 2014–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Gans, D.; Lowenstein, A.; Giarrusso, R.; Bengtson, V.L. Older parent–child relationships in six developed nations: Comparisons at the intersection of affection and conflict. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gaalen, R.I.; Dykstra, P.A. Solidarity and conflict between adult children and parents: A latent class analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Cheng, Q.; Yip, P.S.F. Does gender difference exist in typologies of intergenerational relations? Adult son-parent and daughter-parent relations in Hong Kong. J. Fam. Issues 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Chi, I.; Silverstein, M. The structure of intergenerational relations in rural China: A latent class analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, A. Intergenerational solidarity and ambivalence: Types of relationships in German families. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2008, 39, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Silverstein, M.; Suitor, J.J.; Gilligan, M.; Hwang, W.; Nam, S.; Routh, B. Use of communication technology to maintain intergenerational contact: Toward an understanding of “digital solidarity”. Connect. Fam. 2018, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Social Media Use in 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Fingerman, K.L.; Huo, M.; Birditt, K.S. A decade of research on intergenerational ties: Technological, economic, political, and demographic changes. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, S. (Ed.) Intergenerational solidarity. In Intergenerational Connections in Digital Families; Springer International Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Older Adults. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneed-extra-precautions%2Folder-adults.html (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Antonucci, T.C.; Ajrouch, K.J.; Manalel, J.A. Social relations and technology: Continuity, context, and change. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, igx029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Roth, A.R. Social isolation and loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study of U.S. adults older than 50. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77, e185–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.R.; Netzer, J.K.; Coward, R.T. Depression among older parents: The role of intergenerational exchange. J. Marriage Fam. 1995, 57, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, M.; Cong, Z.; Li, S. Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, S256–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dong, X. The association between filial piety and depressive symptoms among U.S. Chinese older adults. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 4, 2333721418778167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, K.S.; Krause, N. Intergenerational solidarity and psychological well-being among older Mexican Americans: A three-generations study. J. Gerontol. 1985, 40, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, Y.; Li, P. Intergenerational solidarity and life satisfaction among empty-nest older adults in rural China: Does distance matter? J. Fam. Issues 2021, 42, 626–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Stensland, M.; Li, M.; Dong, X. Parent-adult child relations of Chinese older immigrants in the United States: Is there an optimal type? J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Chi, I. Internet use and loneliness of older adults over time: The mediating effect of social contact. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Kim, K.; Silverstein, N.M.; Song, Q.; Burr, J.A. Social media communication and loneliness among older adults: The mediating roles of social support and social contact. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skałacka, K.; Pajestka, G. Digital or in-person: The relationship between mode of interpersonal communication during the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in older adults from 27 countries. J. Fam. Nurs. 2021, 27, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, K.L.; Ng, Y.T.; Zhang, S.; Britt, K.; Colera, G.; Birditt, K.S.; Charles, S.T. Living Alone During COVID-19: Social Contact and Emotional Well-being Among Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021, 76, e116–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H.; Levinsky, M. Social networks and mental health change in older adults after the Covid-19 outbreak. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, T. Intergenerational transfers and European families: Does the number of siblings matter? Demogr. Res. 2013, 29, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, T.; Raab, M.; Engelhardt, H. The transition to parent care: Costs, commitments, and caregiver selection among children. J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 76, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björgvinsson, T.; Kertz, S.J.; Bigda-Peyton, J.S.; McCoy, K.L.; Aderka, I.M. Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment 2013, 20, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechanic, D.; Bradburn, N.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1970, 35, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Accept. Commit. Therapy. Meas. Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson, K.; Choi, A.Y. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolck, A.; Croon, M.; Hagenaars, J. Estimating Latent Structure Models with Categorical Variables: One-Step Versus Three-Step Estimators. Politi-Anal. 2004, 12, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J.K.; Magidson, J. Upgrade Manual for Latent GOLD 5.1; Statistical Innovations Inc.: Belmont, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick, C.; van Groenou, M.B.; Orban, A.; Corrigan, T.; Coimbra, S.; Kirtava, Z.; Holdsworth, C.; Comas-D’Argemir, D.; Aliprant, L.; Gadet, C.; et al. Lessons learned from 11 countries on programs promoting intergenerational solidarity. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedsman, T. Building a humane society for older people: Compassionate policy making for integration, participation, and positive ageing within a framework of intergenerational solidarity. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2017, 15, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Yatnatti, S.K. Intergenerational digital engagement: A way to prevent social isolation during the COVID-19 crisis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1394–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.E.K.; Kim, D.H. Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2019, 29, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Older Adults (n = 519) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M (SD) | n (%) | |

| Demographic Variables | |||

| Age | 69.07 (3.78) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 219 (42.2) | ||

| Female | 297 (57.2) | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 497 (95.8) | ||

| Other ethnic groups | 22 (4.2) | ||

| Education | 1–6 | 3.58 (1.28) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabitating | 410 (79.0) | ||

| Others | 108 (20.8) | ||

| Annual income | 1–11 | 5.68 (3.03) | |

| Health status | |||

| Healthy | 400 (77.1) | ||

| Unhealthy | 119 (22.9) | ||

| Children’s age | 43.27 (7.22) | ||

| Children’s gender | |||

| Son | 270 (52.0) | ||

| Daughter | 247 (47.6) | ||

| Parent–child relations | |||

| Biological or adoptive children | 442 (85.2) | ||

| Stepchildren | 76 (14.6) | ||

| Number of children | 2.75 (1.47) | ||

| Intergenerational Solidarity | |||

| Affectual solidarity | 1–6 | 4.26 (1.48) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 134 (25.8) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 385 (74.2) | ||

| Consensual solidarity | 1–6 | 3.97 (1.31) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 169 (32.6) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 341 (65.7) | ||

| Associational solidarity: In-person contact | 1–6 | 3.32 (1.38) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 289 (55.7) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 228 (43.9) | ||

| Associational solidarity: Phone contact | 1–6 | 3.91 (1.41) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 173 (33.3) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 344 (66.3) | ||

| Digital solidarity: Texting | 1–6 | 3.88 (1.66) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 194 (37.4) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 324 (62.4) | ||

| Digital solidarity: Video call | 1–6 | 2.05 (1.56) a | |

| Low group (range 1–2) | 361 (69.6) | ||

| High group (range 3–6) | 155 (29.9) | ||

| Intergenerational Solidarity | |||

| Digital solidarity: Social media | 1–6 | 1.96 (1.34) a | |

| Low group (range 1–2) | 363 (69.9) | ||

| High group (range 3–6) | 152 (29.3) | ||

| Structural solidarity | 1–6 | 3.29 (1.94) | |

| Low group (range 1–3) | 251 (48.4) | ||

| High group (range 4–6) | 267 (51.4) | ||

| Conflict | 1–6 | 2.02 (1.30) a | |

| Low group (range 1–2) | 388 (74.8) | ||

| High group (range 3–6) | 128 (24.7) | ||

| Mental Health | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 1–4 | 1.59 (0.44) | |

| Psychological well-being | 0–10 | 7.46 (1.98) | |

| Self-esteem | 1–4 | 3.43 (0.46) | |

| Model | Classes (n) | BIC | CAIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1 | 5902.04 | 5911.04 | - |

| Model 2 | 2 | 5386.61 | 5405.61 | 0.80 |

| Model 3 | 3 | 5255.24 | 5284.24 | 0.81 |

| Model 4 | 4 | 5236.76 | 5275.76 | 0.80 |

| Model 5 | 5 | 5249.59 | 5298.59 | 0.83 |

| Model 6 | 6 | 5276.17 | 5335.17 | 0.82 |

| Variables | Older Adults (n = 519) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | Psychological Well-Being | Self-Esteem | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Class Memberships (ref: Detached) | |||

| Distant-but-digitally connected | −0.12 (0.06) † | 0.65 (0.28) * | 0.26 (0.06) *** |

| Tight-knit-traditional | −0.11 (0.06) † | 0.73 (0.27) ** | 0.24 (0.06) *** |

| Ambivalent | 0.17 (0.08) * | −0.59 (0.36) | 0.04 (0.08) |

| Covariates | |||

| Age | −0.00 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.02) | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Female (ref: male) | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.22 (0.17) | −0.06 (0.04) |

| White (ref: others) | −0.02 (0.08) | −0.93 (0.33) ** | −0.09 (0.07) |

| Education | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Married/cohabiting (ref: others) | −0.16 (0.05) ** | 0.59 (0.23) * | 0.11 (0.05) * |

| Annual income | −0.01 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.00) * |

| Healthy (ref: unhealthy) | 0.08 (0.04) | −0.06 (0.20) | −0.04 (0.04) |

| Children’s age | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.00 (0.00) |

| Daughters (ref: sons) | −0.00 (0.03) | −0.14 (0.17) | 0.00 (0.03) |

| Biological/adoptive children (ref: stepchildren) | 0.14 (0.05) * | −0.77 (0.26) ** | −0.15 (0.06) * |

| Class 1 Distant-But-Digitally Connected | Class 2 Tight-Knit-Traditional | Class 3 Detached | Class 4 Ambivalent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | M (SE) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | p-value |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.52 (0.03) | 1.53 (0.03) | 1.64 (0.05) | 1.82 (0.06) | 4 > 1 & 2 *** 4 > 3 * 3 > 1 & 2 † |

| Psychological well-being | 7.77 (0.15) | 7.85 (0.15) | 7.12 (0.22) | 6.52 (0.28) | 1 & 2 > 4 *** 1 > 3 * 2 > 3 ** |

| Self-esteem | 3.54 (0.03) | 3.52 (0.03) | 3.27 (0.05) | 3.32 (0.06) | 1 & 2 > 3 *** 1 & 2 > 4 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, W.; Fu, X.; Brown, M.T.; Silverstein, M. Digital and Non-Digital Solidarity between Older Parents and Their Middle-Aged Children: Associations with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912560

Hwang W, Fu X, Brown MT, Silverstein M. Digital and Non-Digital Solidarity between Older Parents and Their Middle-Aged Children: Associations with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912560

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Woosang, Xiaoyu Fu, Maria Teresa Brown, and Merril Silverstein. 2022. "Digital and Non-Digital Solidarity between Older Parents and Their Middle-Aged Children: Associations with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912560

APA StyleHwang, W., Fu, X., Brown, M. T., & Silverstein, M. (2022). Digital and Non-Digital Solidarity between Older Parents and Their Middle-Aged Children: Associations with Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912560