Assessing Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students at the University of Milan, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Questionnaire for the Assessment of Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

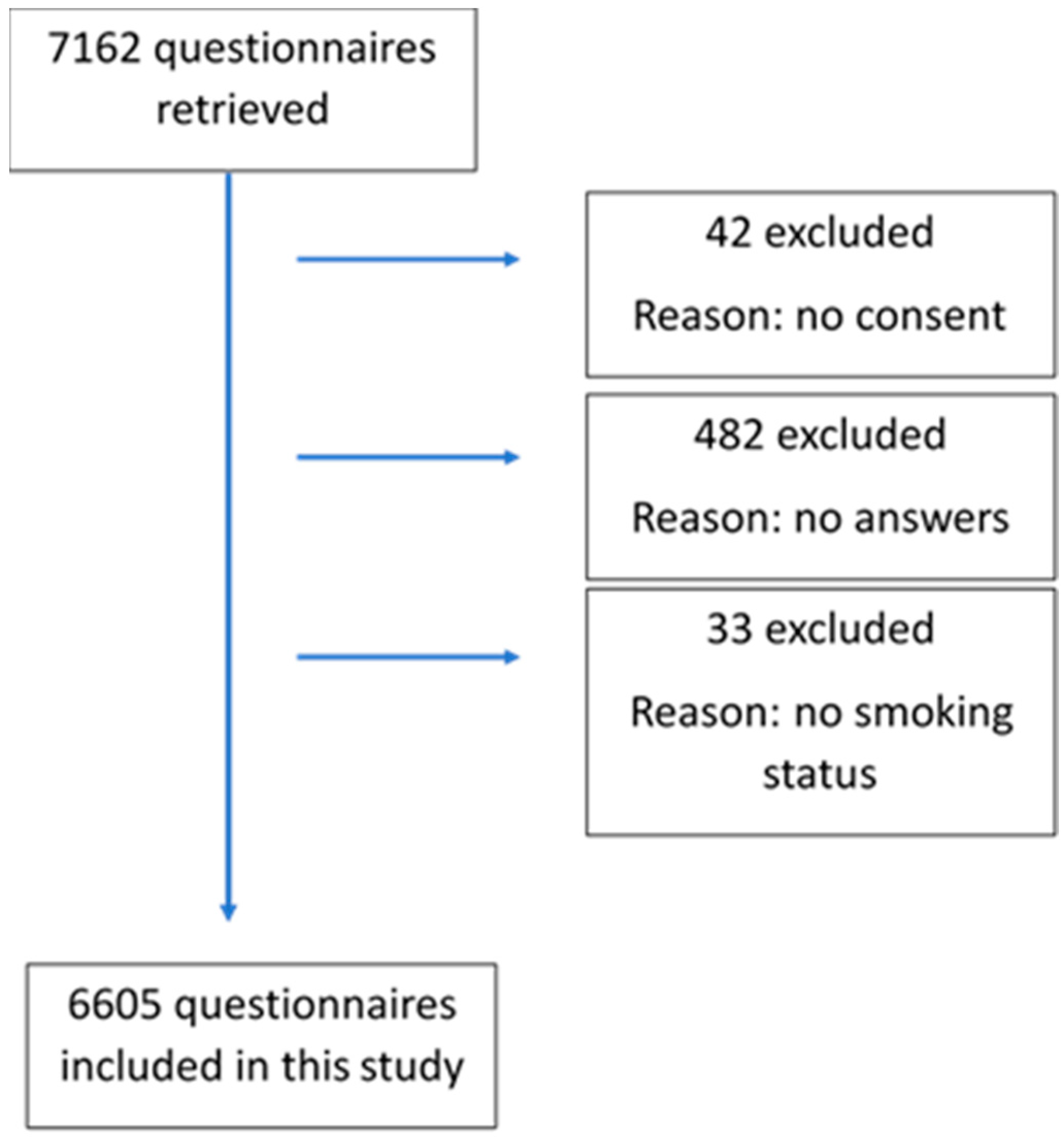

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Active Smoking Habits

3.3. Active Smoking of Traditional Tobacco Cigarettes

3.4. Electronic Cigarettes or HTP Use

3.5. Passive Smoking

3.6. Awareness of Smoking Health-Related Issues and Role of Healthcare Professionals

3.7. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Smoking Legislation and Policy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD). 2019. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/gbd/summaries (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Ministero Della Salute. Prevenzione e Controllo Del Tabagismo-Rapporto Anno 2018 [In Italian]. 2019. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/documentazione/p6_2_2_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=2851 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Gallus, S.; Muttarak, R.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Zuccaro, P.; Colombo, P.; La Vecchia, C. Smoking prevalence and smoking attributable mortality in Italy, 2010. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, E.; Osuji, N.; Erhabor, J.; Obisesan, O.; Osei, A.D.; Mirbolouk, M.; Stokes, A.C.; Dzaye, O.; El Shahawy, O.; Hirsch, G.A.; et al. Assessment of Patterns in e-Cigarette Use among Adults in the US, 2017–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2223266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lugo, A.; Davoli, E.; Gorini, G.; Pacifici, R.; Fernández, E.; Gallus, S. Electronic cigarettes in Italy: A tool for harm reduction or a gateway to smoking tobacco? Tob. Control 2019, 29, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillen, R.; Maduka, J.; Winickoff, J. Use of Emerging Tobacco Products in the United States. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 989474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). 2003. Available online: https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/overview (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Italian Legislation, Law Decree 104, Art. 4, 12 September 2013 (Misure Urgenti in Materia di Istruzione, Universita’ e Ricerca. (13G00147)) Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Generale n.214, 12 September 2013, Enforced from 12 September 2013. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2013/09/12/13G00147/sg (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- ESPAD Group. ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, P.M.; Glantz, S.A. Why and How the Tobacco Industry Sells Cigarettes to Young Adults: Evidence From Industry Documents. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.L.; Deiner, M.; Pokhrel, P. College anti-smoking policies and student smoking behavior: A review of the literature. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2017, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, B.P.; Walley, S.C.; Groner, J.A.; Rahmandar, M.; Boykan, R.; Mih, B.; Marbin, J.N.; Caldwell, A.L. Section on Tobacco Control. E-Cigarettes and Similar Devices. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, E.; Lechner, W.V.; Miller, M.B.; Wiener, J.L. Changes in Smokeless Tobacco Use over Four Years Following a Campus-Wide Anti-tobacco Intervention. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.-C.; Macy, J.T.; Torabi, M.R.; Middlestadt, S.E. The effect of a smoke-free campus policy on college students’ smoking behaviors and attitudes. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.; Ranney, L.M.; Goldstein, A.O. Cigarette butts near building entrances: What is the impact of smoke-free college campus policies? Tob. Control 2013, 22, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.; Hart, E.; Jancey, J.; Hallett, J.; Crawford, G.; Portsmouth, L. A cross sectional evaluation of a total smoking ban at a large Australian university. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, L.; Vecera, F.; Fustinoni, S. Validation of a Questionnaire to Assess Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students: A Pilot Study among Obstetrics Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The GTSS Collaborative Group Tobacco use and cessation counselling: Global Health Professionals Survey Pilot Study, 10 countries, 2005. Tob. Control 2006, 15, ii31–ii34. [CrossRef]

- Rodakowska, E.; Mazur, M.; Baginska, J.; Sierpinska, T.; La Torre, G.; Ottolenghi, L.; D’Egidio, V.; Guerra, F. Smoking Prevalence, Attitudes and Behavior among Dental Students in Poland and Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigitano, A.; Binda, S.; Pariani, E. Tobacco and e-cigarette smoking habits among Italian healthcare students. Ann. Ig 2020, 32, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.W.; Veronese, G.; George, P.F.; Montroni, I.; Ugolini, G. Assessment of Tobacco Habits, Attitudes, and Education Among Medical Students in the United States and Italy: A Cross-sectional Survey. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2017, 50, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Kirch, W.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Ramos, R.; Czaplicki, M.; Gualano, M.; Thümmler, K.; Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, A. Tobacco use among medical students in Europe: Results of a multicentre study using the Global Health Professions Student Survey. Public Health 2011, 126, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzillo, E.M.; Monaco, M.G.L.; Corvino, A.R.; Giardiello, A.; Arnese, A.; Napolitano, F.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Lamberti, M. Smoking Habits and Workplace Health Promotion among University Students in Southern Italy: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, L.A.; Batanova, M.; Loukas, A. Prevalence and Harm Perceptions of Various Tobacco Products among College Students. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 16, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamamili, B.; Wallace-Bell, M.; Richardson, A.; Grace, R.C.; Coope, P. Cigarette smoking among university students aged 18–24 years in New Zealand: Results of the first (baseline) of two national surveys. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdro-Zastawny, K.; Dorobisz, K.; Bobak-Sarnowska, E.; Zatoński, T. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Cigarette Smoking Among Medical Students in Wroclaw, Poland. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2022, 15, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šljivo, A.; Ćetković, A.; Hašimbegović-Spahić, D.; Mlačo, N.; Mujičić, E.; Selimović, A. Patterns of cigarette, hookah and other tobacco product consumption habits among undergraduate students of the University of Sarajevo before the COVID-19 outbreak in Bosnia and Hercegovina, a cross-sectional study. Ann. Ig 2022, 34, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, E.; Faubl, N.; Riemenschneider, H.; Balázs, P.; Bergmann, A.; Cseh, K.; Horváth, F.; Schelling, J.; Terebessy, A.; Wagner, Z.; et al. Cigarette, waterpipe and e-cigarette use among an international sample of medical students. Cross-sectional multicenter study in Germany and Hungary. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brożek, G.M.; Jankowski, M.; Lawson, J.A.; Shpakou, A.; Poznański, M.; Zielonka, T.M.; Klimatckaia, L.; Loginovich, Y.; Rachel, M.; Gereová, J.; et al. The Prevalence of Cigarette and E-cigarette Smoking among Students in Central and Eastern Europe—Results of the YUPESS Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS). Available online: https://www.iss.it/web/guest//comunicati-stampa//asset_publisher/fjTKmjJgSgdK/content/id/7146126 (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Wamamili, B.; Lawler, S.; Wallace-Bell, M.; Gartner, C.; Sellars, D.; Grace, R.C.; Courtney, R.; Coope, P. Cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use among university students in Queensland, Australia and New Zealand: Results of two cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Omari, O.; Abu Sharour, L.; Heslop, K.; Wynaden, D.; Alkhawaldeh, A.; Al Qadire, M.; Khalaf, A. Knowledge, Attitudes, Prevalence and Associated Factors of Cigarette Smoking among University Students: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Community Health 2020, 46, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sawalha, N.A.; Almomani, B.A.; Mokhemer, E.; Al-Shatnawi, S.F.; Bdeir, R. E-cigarettes use among university students in Jordan: Perception and related knowledge. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0262090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzano, S.; Santangelo, O.; Grigis, D.; Giordano, D.; Firenze, A. Smoking behaviour among nursing students: Attitudes toward smoking cessation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2019, 60, E203–E210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Egidio, V.; Patrissi, R.; De Vivo, G. Global Health Professions Student Survey among Healthcare students: A cross sectional study. Ann Ig 2020, 32, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bold, K.W.; Kong, G.; Camenga, D.R.; Simon, P.; Cavallo, D.A.; Morean, M.E.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Trajectories of E-Cigarette and Conventional Cigarette Use Among Youth. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20171832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking; WHO (World Health Organization): Lyon, France, 2004; Volume 83. [Google Scholar]

- Czogala, J.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Fidelus, B.; Zielinska-Danch, W.; Travers, M.J.; Sobczak, A. Secondhand Exposure to Vapors from Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 16, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan-Lyon, P. Electronic cigarettes: Human health effects. Tob. Control 2014, 23, ii36–ii40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.C.L.; Skjerven, H.O.; Carlsen, K.-H. The toxicity of E-cigarettes and children’s respiratory health. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2018, 28, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, L.; Boniardi, L.; Polledri, E.; Longhi, F.; Scuffi, C.; Fustinoni, S. Smoking habit in parents and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in elementary school children of Milan. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancey, J.; Bowser, N.; Burns, S.; Crawford, G.; Portsmouth, L.; Smith, J. No Smoking Here: Examining Reasons for Noncompliance With a Smoke-Free Policy in a Large University. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 16, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeier, B.S.; Chapp, C.B.; Henley, W.B. Improving Tobacco-Free Advocacy on College Campuses: A Novel Strategy to Aid in the Understanding of Student Perceptions about Policy Proposals. J. Am. Coll. Health 2014, 62, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Students Participating to the Survey N (%) | Student Population N (%) | Participation Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 2408 (36.5) | 26,233 (40.5) | 9.2 |

| Female | 4105 (62.1) | 38,568 (59.5) | 10.6 | |

| intersex | 19 (0.3%) | n.a. | - | |

| not declared | 73 (1.1%) | n.a. | - | |

| Age (year) | 18–25 years | 5555 (84.1) | 51,128 (78.9) | 10.9 |

| ≥26 years | 1050 (15.9) | 13,673 (21.1) | 7.7 | |

| Faculty | Law | 441 (6.7) | 6835 (10.5) | 6.5 |

| PESS | 891 (13.5) | 8240 (12.7) | 10.8 | |

| Hum | 1447 (21.9) | 15,795 (24.4) | 9.2 | |

| Med | 969 (14.7) | 8132 (12.5) | 11.9 | |

| Pha | 486 (7.4) | 3946 (6.1) | 12.3 | |

| STE | 1353 (20.5) | 9978 (15.4) | 13.6 | |

| Agr | 350 (5.3) | 3485 (5.4) | 10.0 | |

| Vet | 170 (2.6) | 1492 (2.3) | 11.4 | |

| LMIC | 401 (6.1) | 5578 (8.6) | 7.2 | |

| Sport | 97 (1.5) | 1320 (2.1) | 7.3 | |

| Characteristics | Nonsmokers | Smokers/Vapers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never Smokers N (%) | Former Smokers N (%) | Total Nonsmokers 1 N (%) | Tobacco Cigarettes Only N (%) | e-cigs/HTPs Only N (%) | Dual 2 N (%) | Total Smokers/Vapers 3 N (%) | ||

| All subjects | 4212 (63.8) | 687 (10.4) | 4899 (74.2) | 1278 (19.3) | 184 (2.8%) | 244 (3.7%) | 1706 (25.8) | |

| Sex | Male | 1430 (59.4) | 275 (11.4) | 1705 (70.8) | 538 (22.3) | 70 (2.9) | 95 (3.9) | 703 (29.2) |

| Female | 2734 (66.6) | 403 (9.8) | 3137 (76.4) | 710 (17.3) | 114 (2.8) | 144 (3.5) | 968 (23.6) | |

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 3608 (65.0) | 485 (8.7) | 4093 (73.7) | 1097 (19.7) | 153 (2.8) | 212 (3.8) | 1462 (26.3) |

| ≥26 | 604 (57.5) | 202 (19.3) | 806 (76.7) | 181 (17.2) | 31 (3.0) | 32 (3.0) | 244 (23.3) | |

| Faculty | Law | 232 (52.6) | 61 (13.8%) | 293 (66.4) | 103 (23.4) D,E,F | 18 (4.1) | 27 (6.1) | 148 (33.6) D,E,F |

| PESS | 481 (54.0) | 97 (10.9) | 587 (64.9) | 235 (26.4) D,E,F,G,H | 35 (3.9) | 43 (4.8) | 313 (35.1) D,E,F,G,H,I | |

| Hum | 841 (58.1) | 169 (11.7) | 1010 (69.8) | 354 (24.5) D,E,F,H | 31 (2.1) | 52 (3.6) | 437 (30.2) D,E,F | |

| Med | 692 (71.4) A,B,C | 93 (9.6) | 785 (81.0) | 144 (14.9) | 19 (2.0) | 21 (2.2) | 184 (19.1) | |

| Pha | 339 (69.8) A,B,C | 49 (10.1) | 388 (79.9) | 57 (11.7) | 19 (3.9) | 22 (4.5) | 98 (20.1) | |

| STE | 942 (69.6) A,B,C | 120 (8.9) | 1062 (78.5) | 215 (15.9) | 34 (2.5) | 42 (3.1) | 291 (21.5) | |

| Agr | 232 (66.3) A,B | 40 (11.4) | 272 (77.7) | 60 (17.1) | 8 (2.3) | 10 (2.9) | 78 (22.3) | |

| Vet | 119 (70.0) A,B | 14 (8.2) | 133 (78.2) | 22 (12.9) | 6 (3.5) | 9 (5.3) | 37 (21.7) | |

| LMIC | 264 (65.8) A,B | 37 (9.2) | 301 (75.0) | 74 (18.5) | 14 (3.5) | 12 (3.0) | 100 (25.0) | |

| Sport | 70 (72.2) A,B | 7 (7.2) | 77 (79.4) | 14 (14.4) | 0 | 6 (6.2) | 20 (20.6) | |

| How Often Do You Currently Smoke? | Have You Ever Tried to Quit Traditional Cigarettes? | Have You Ever Been Advised by a Doctor or Other Healthcare Professional to Quit Smoking Traditional Cigarettes? | Are You Planning to Quit Smoking Traditional Cigarettes in the Next Six Months? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily a N (%) | Yes b N (%) | Yes N (%) | No N (%) | Don’t Remember N (%) | Yes N (%) | No N (%) | Don’t Know N (%) | |

| All subjects | 1173 (77.3) | 899 (59.4) | 554 (36.6) | 812 (53.7) | 146 (9.7%) | 322 (21.3) | 610 (40.3) | 580 (38.4) |

| Law | 102 (78,5) | 78 (60.9) | 50 (39.1) | 58 (45.3) | 20 (15.6) | 22 (17.2) | 55 (43.0) | 51 (39.8) |

| PESS | 217 (78.6) | 163 (59.3) | 86 (31.4) | 162 (59.1) D | 26 (9.5) | 75 (27.4) | 108 (39.4) | 91 (33.2) |

| Hum | 316 (78.0) | 228 (56.3) | 149 (36.8) | 211 (52.1) | 45 (11.1) | 69 (17.0) | 174 (43.0) | 162 40.0) |

| Med | 123 (75.0) | 102 (62.2) | 87 (53.0) B,C,E,F | 66 (40.2) | 11 (6.7) | 38 (23.2) | 62 (37.8) | 64 (39.0) |

| Pha | 58 (73.4) | 46 (59.0) | 22 (28.6) | 47 (61.0) | 8 (10.4) | 21 (27.3) | 26 (33.8) | 30 (39.0) |

| STE | 207 (80.5) | 157 (61.1) | 81 (31.5) | 159 (61.9) D | 17 (6.6) | 53 (20.6) | 106 (41.2) | 98 (38.1) |

| Agr | 55 (78.6) | 42 (60.0) | 29 (41.4) | 33 (47.1) | 8 (11.49 | 11 (15.7) | 33 (47.1) | 26 (37.1) |

| Vet | 22 (71.0) | 19 (61.3) | 8 (25.8) | 20 (64.5) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 11 (35.5) | 16 (51.6) |

| LMIC | 60 (69.8) | 48 (55.8) | 33 (38.4) | 47 (54.7) | 6 (7.0) | 21 (24.4) | 26 (30.2) | 39 (45.3) |

| Sport | 13 (65.0) | 16 (80.0) | 9 (45.0) | 9 (45.0) | 2 (10.0) | 8 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) | 3 (15.0) |

| p * | 0.486 | 0.677 | 0.001 | 0.041 | ||||

| Have You Been Exposed for at Least 10 Min over the Last Week? | Do You Live with Smokers? | Do You Usually Spend Leisure Time with Smokers? | In Your House, Traditional Cigarettes Are: | In Your House, e-cigs/HTPs Are: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes a N (%) | Yes a N (%) | Yes a N (%) | Totally Banned N (%) | Allowed in Some Rooms N (%) | Allowed Only Outdoors N (%) | Allowed Everywhere N (%) | Totally Banned N (%) | Allowed in Some Rooms N (%) | Allowed Only Outdoors N (%) | Allowed Everywhere N (%) | |

| All subjects | 2698 (41.0) | 2269 (34.4) | 4358 (66.3) | 2786 (42.4) | 514 (7.8) | 2907 (44.2) | 367 (5.6) | 2785 (42.4) | 611 (9.3) | 2195 (33.4) | 983 (15.0) |

| Law | 193 (44.3) | 172 (39.4) D | 318 (72.9) D,E,F | 165 (37.8) | 44 (10.1) D | 209 (47.9) | 18 (4.1) | 165 (37.8) | 57 (13.1) D | 140 (32.1) | 74 (17.0) |

| PESS | 430 (48.6) C.D.E.F | 329 (37.2) D | 662 (74.9) C,D,E,F,G,H,I | 344 (38.9) | 79 (8.9)D | 405 (45.8) | 56 (6.3) | 349 (39.5) | 105 (11.9) D | 279 (31.6) | 151 (17.1) D |

| Hum | 561 (38.9) | 541 (37.5) D,F | 974 (67.5) | 527 (36.6) | 145 (10.1) D;H | 676 (46.9) D | 93 (6.5) | 548 (38.0) | 148 (10.3) D | 504 (35.0) | 241 (16.7) D |

| Med | 383 (39.6) | 284 (29.4) | 601 (62.2) | 491 (50.8) A,B,C,F,I | 46 (4.8) | 388 (40.2) | 41 (4.2) | 480 (49.7) A,B,C,I | 46 (4.8) | 329 (34.1) | 111 (11.5) |

| Pha | 184 (38.1) | 164 (33.9) | 302 (62.5) | 229 (47.4) C | 35 (7.2) | 196 (40.6) | 23 (4.8) | 218 (45.1) | 45 (9.3) D | 151 (31.3) | 69 (14.3) |

| STE | 511 (37.8) | 427 (31.6) | 849 (62.8) | 593 (43.9) C | 93 (6.9) | 584 (43.3) | 80 (5.9 | 586 (43.4) | 119 (8.8) D | 457 (33.9) | 188 (13.9) |

| Agr | 153 (43.8) | 109 (31.1) | 219 (62.8) | 164 (47.1) C | 30 (8.6) | 137 (39.4) | 17 (4.9) | 159 (45.7) | 28 (8.0) | 105 (30.2) | 56 (16.1) |

| Vet | 61 (35.9) | 61 (35.9) | 106 (62.4) | 73 (42.9) | 4 (2.4) | 86 (50.6) | 7 (4.1) | 77 (45.3) | 11 (6.5) | 64 (37.6) | 18 (10.6) |

| LMIC | 176 (44.1) | 152 (38.1) | 263 (65.9) | 148 (37.1) | 36 (9.0) | 189 (47.4) | 26 (6.5) | 149 (37.3) | 47 (11.8) D | 143 (35.8) | 60 (15.0) |

| Sport | 46 (47.4) | 30 (30.9) | 64 (66.0) | 52 (53.6) C | 2 (2.1) | 37 (38.1) | 6 (6.2) | 54 (55.7) C,I | 5 (5.2) | 23 (23.7) | 15 (15.5) |

| p * | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Are You Aware That It Is Forbidden to Throw Cigarette Butts on the Ground? | Are You Aware of the Damage Caused by Cigarette Butts in the Environment? | Are You Aware That It Is Forbidden to Smoke and Vape in the Outdoor Areas of Schools and Universities? | Are You Aware That the University of Milan Has Anti-Smoking Regulations? | What Initiatives Could the University of Milan Undertake to Help Smokers Quit Smoking and Protect the Health of Non-Smokers? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes a N (%) | Yes a N (%) | Yes a N (%) | Yes a N (%) | Informative Campaigns | Greater Control over Compliance with Bans | Courses on Smoking Issues | Cessation Aid | |

| All subjects | 5789 (88.5) | 5977 (91.3) | 3117 (47.6) | 3233 (49.4) | 2064 (39.8) | 4166 (63.7) | 1627 (24.9) | 3560 (54.4) |

| Law | 397 (91.1) | 408 (93.6) J | 226 (51.8) | 233 (53.4) J | 170 (38.5) | 280 (63.5) | 113 (25.6) | 207 (46.9) |

| PESS | 771 (87.3) | 797 (90.3) | 400 (45.3) | 391 (44.3) | 355 (39.8) | 534 (59.9) | 191 (21.4) | 468 (52.5) |

| Hum | 1288 (89.8) | 1344 (93.7) D,J | 703 (49.0) | 727 (50.7) J | 566 (39.1) | 863 (59.6) | 368 (25.4) | 743 (51.3) |

| Med | 843 (88.2) | 847 (88.6) | 485 (50.7) | 520 (54.4) B,I,J | 399 (41.2) | 654 (67.5) B,C | 319 (32.9) B,C,F,G,I | 617 (63.7) A,B,C,E,F |

| Pha | 419 (87.1) | 439 (91.3) | 246 (51.1) | 245 (50.9) J | 209 (43.0) | 338 (69.5) B,C | 128 (26.3) | 245 (50.4) |

| STE | 1182 (87.8) | 1218 (90.4) | 613 (45.5) | 668 (49.6) J | 515 (38.1) | 843 (62.3) | 275 (20.3) | 707 (52.3) |

| Agr | 305 (88.7) | 318 (92.7) | 148 (43.0) | 159 (46.2) | 130 (37.1) | 212 (60.6) | 75 (21.4) | 196 (56.0) |

| Vet | 151 (89.3) | 157 (92.9) | 68 (40.2) | 82 (48.5) | 63 (37.1) | 118 (69.4) | 42 (24.7) | 101 (59.4) |

| LMIC | 345 (86.7) | 369 (92.7) | 184 (46.2) | 177 (44.5) | 151 (37.7) | 270 (67.3) | 89 (22.2) | 220 (54.9) |

| Sport | 88 (91.7) | 80 (83.3) | 44 (45.8) | 31 (32.3) | 46 (47.4) | 54 (55.7) | 27 (27.8) | 56 (57.7) |

| p * | 0.308 | <0.001 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.397 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campo, L.; Lumia, S.; Fustinoni, S. Assessing Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students at the University of Milan, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912527

Campo L, Lumia S, Fustinoni S. Assessing Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students at the University of Milan, Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912527

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampo, Laura, Silvia Lumia, and Silvia Fustinoni. 2022. "Assessing Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students at the University of Milan, Italy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912527

APA StyleCampo, L., Lumia, S., & Fustinoni, S. (2022). Assessing Smoking Habits, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Needs among University Students at the University of Milan, Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912527