Building Capacity for Community-Academia Research Partnerships by Establishing a Physical Infrastructure for Community Engagement: Morgan CARES

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

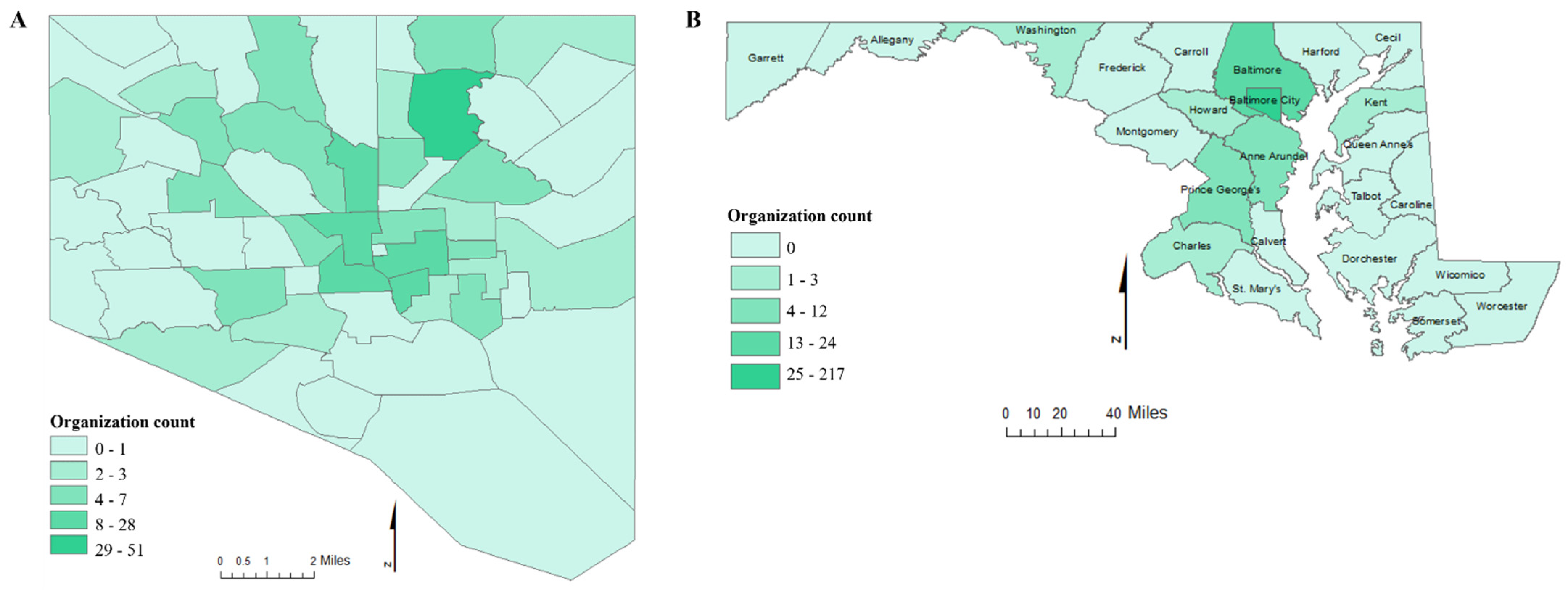

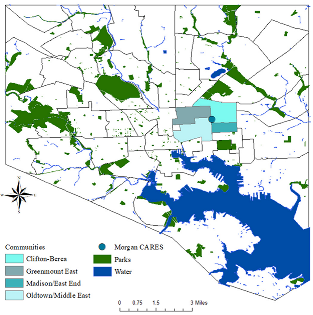

2.1. Setting

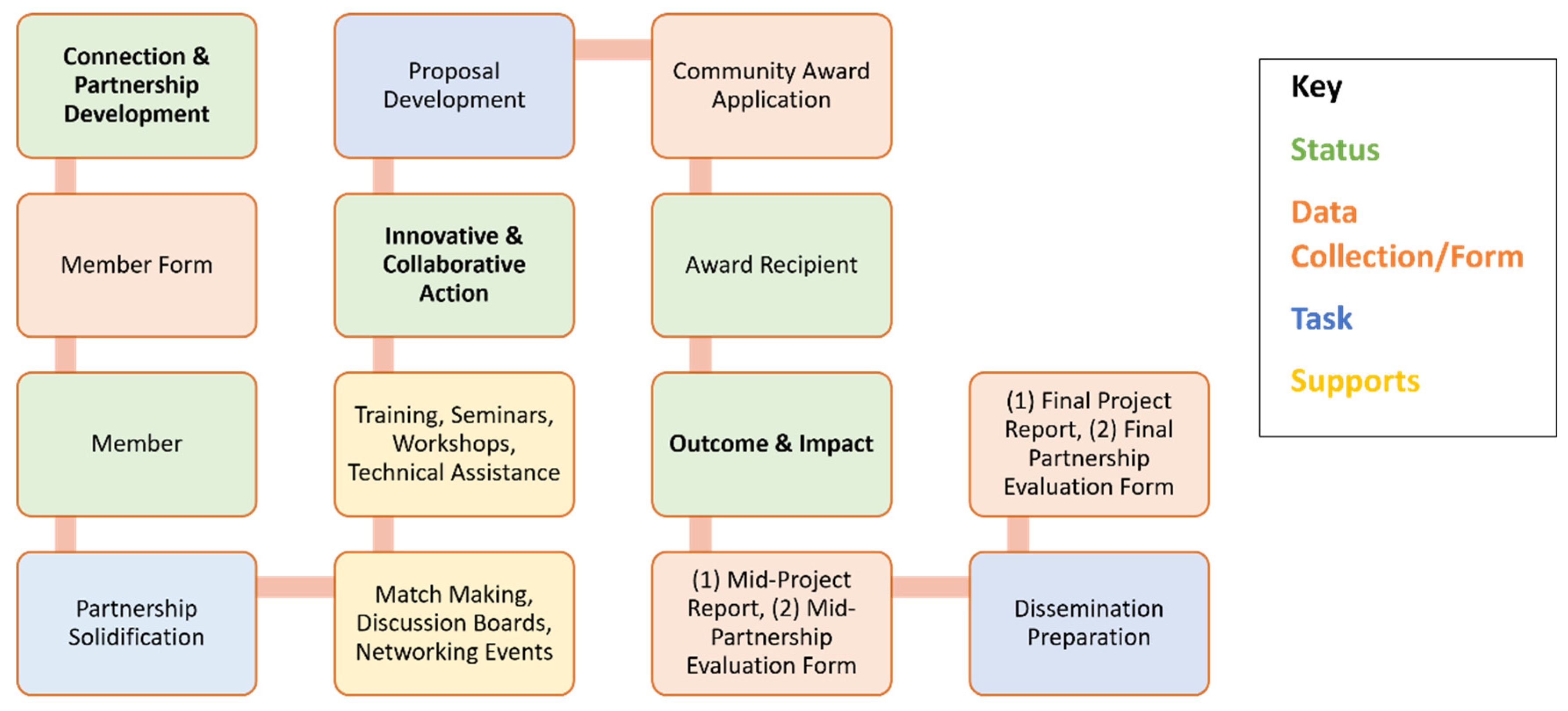

2.2. Morgan CARES Model

2.3. Community Needs Assessment

2.4. Morgan CARES Community Award Program and Projects

2.4.1. Connection and Partnership Development

2.4.2. Innovation and Collaborative Action

2.4.3. Outcome and Impact

2.5. Metrics Measure Evaluation Designs

3. Results

3.1. Identifying Community Challenges Perceived by Community Stakeholders

3.2. Morgan CARES Network Services and Community Award Initiatives

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freire, P. Reading the world and reading the word: An interview with Paulo Freire. Lang. Arts 1985, 62, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B.; Allen, A.J.; Guzman, J.R.; Lichtenstein, R. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. Community-Based Particip. Res. Health Adv. Soc. Health Equity 2017, 3, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N. Commentary: Challenges for the field in overcoming disparities through a CBPR approach. Ethn. Dis. 2006, 16 (Suppl. 1), S146–S148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newman, S.D.; Andrews, J.O.; Magwood, G.S.; Jenkins, C.; Cox, M.J.; Williamson, D.C. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2011, 8, A70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Stanton, J.; The Leap Advisory Board; Straits, K.J.E.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Rodriguez Espinosa, P.; Nicasio, A.V.; Andrasik, M.P.; Hawes, S.M.; et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelic, S.L.; Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G. Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: Development and testing of a model. In Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advaning Social and Health Equity, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 3, p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Mikesell, L.; Bromley, E.; Khodyakov, D. Ethical community-engaged research: A literature review. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e7–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, B.L.; Mentz, G.; Jensen, M.; Jacobs, B.; Saylor, K.M.; Rowe, Z.; Israel, B.A.; Lachance, L. Success in Long-Standing Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Partnerships: A Scoping Literature Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egid, B.; Ozano, K.; Hegel, G.; Zimmerman, E.; López, Y.; Roura, M.; Sheikhattari, P.; Jones, L.; Dias, S.; Wallerstein, N. Can everyone hear me? Reflections on the use of global online workshops for promoting inclusive knowledge generation. Qual. Res. 2021, 14687941211019585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhattari, P.; Apata, J.; Kamangar, F.; Schutzman, C.; O’Keefe, A.; Buccheri, J.; Wagner, F.A. Examining Smoking Cessation in a Community-Based Versus Clinic-Based Intervention Using Community-Based Participatory Research. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaven, M.J.; Gimpel, N.A.; Kitzman, H. Working with communities: Meeting the health needs of those living in vulnerable communities when Primary Health Care and Universal Health Care are not available. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, R.; Keeler, H.; Strong, S.; Lyden, E.R.; Davis, P.; Grant, B.K.; Marcelin, J.R. Building structural competency through community engagement. Clin. Teach. 2021, 18, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan State Univers, Office of Public Relations & Strategic Communications. Morgan Community Mile Celebrates Two Years of Accomplishments: Office of Public Relations & Strategic Communications. 2015. Available online: https://news.morgan.edu/morgan-community-mile-celebrates-two-years-of-accomplishments/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Deneia Washington. Morgan’s Community Mile Bridges the Town-Gown Divide Batimore City Paper 2016. Available online: https://www.baltimoresun.com/citypaper/bcp-feature-morgan-community-mile-20160907-story.html (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Morgan Community Mile. Available online: https://www.morgan.edu/research-and-economic-development/outreach-programs/morgan-community-mile?page_id=1155 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- 31 Homes in Baltimore Receive Solar through Partnership 2017. Available online: https://gridalternatives.org/sites/default/files/Morgan%20Community%20Mile%20Press%20Release.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Elizabeth Heubeck. Morgan State University Unveils Plan to Boost Neighborhood: Bmore. 2013. Available online: https://bmoremedia.com/features/morgancommunitymile051413.aspx (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Tatyana Turner. Amid Pandemic, Baltimore’s Black-Owned Businesses Struggle—But Some Are Finding New, Sup-Port. The Baltimore Sun. 2020. Available online: https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/baltimore-city/bs-md-black-businesses-find-support-amid-pandemic-20200807-tqh4ggx37nfuhe76x3fcbnyzxu-story.html (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Wagner, F.A.; Sheikhattari, P.; Buccheri, J.; Gunning, M.; Bleich, L.; Schutzman, C. A Community-Based Participatory Research on Smoking Cessation Intervention for Urban Communities. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, N.; Belone, L.; Burgess, E.; Dickson, E.; Gibbs, L.; Parajon, L.C.; Ramgard, M.; Sheikhattari; Silver, G. Community Based Participatory Research: Embracing Praxis for Transformation; Howard, J., Ospina, S., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 663–679. [Google Scholar]

- Henry Akintobi, T.; Sheikhattari, P.; Shaffer, E.; Evans, C.L.; Braun, K.L.; Sy, A.U.; Mancera, B.; Campa, A.; Miller, S.T.; Sarpong, D.; et al. Community Engagement Practices at Research Centers in U.S. Minority Institutions: Priority Populations and Innovative Approaches to Advancing Health Disparities Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fushion Partnership. Available online: https://www.fusiongroup.org/index.php (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Sanchez, V.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Dickson, E.; Burgess, E.; Haozous, E.; Trickett, E.; Baker, E.; Wallerstein, N. CBPR Implementation Framework for Community-Academic Partnerships. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 67, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursaw, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Dickson, E.; Thein, T.S.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Pena, J.; Parker, M.; Magarati, M.; Littledeer, L.; Duran, B.; et al. Scales of Practices and Outcomes for Community-Engaged Research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 67, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.F.; Loup, A.; Nelson, R.M.; Botkin, J.R.; Kost, R.; Smith, G.R.; Gehlert, S. The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: Points to consider. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics. 2010, 5, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Rumana, N.; Lasker, M.A.A.; Qasqas, M. Partnering with organisations beyond academia through strategic collaboration for research and mobilisation in immigrant/ethnic-minority communities. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Oetzel, J.G.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Boursaw, B.; Dickson, E.; Kastelic, S.; Koegel, P.; Lucero, J.E.; Magarati, M.; Ortiz, K.; et al. Engage for Equity: A Long-Term Study of Community-Based Participatory Research and Community-Engaged Research Practices and Outcomes. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore de Peralta, A.; Prieto Rosas, V.; Smithwick, J.; Timmons, S.M.; Torres, M.E. A Contribution to Measure Partnership Trust in Community-Based Participatory Research and Interventions with Latinx Communities in the United States. Health Promot. Pract. 2022, 23, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, H.; Errett, N.A.; Eisenman, D.P. Working with Disaster-Affected Communities to Envision Healthier Futures: A Trauma-Informed Approach to Post-Disaster Recovery Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B. Building a Path to Resilience in Baltimore; Groundswell: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2020; Available online: https://groundtruth.groundswell.org/building-a-path-to-resilience-in-baltimore/ (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Akintobi, T.H.; Lockamy, E.; Goodin, L.; Hernandez, N.D.; Slocumb, T.; Blumenthal, D.; Braithwaite, R.; Leeks, L.; Rowland, M.; Cotton, T.; et al. Processes and Outcomes of a Community-Based Participatory Research-Driven Health Needs Assessment: A Tool for Moving Health Disparity Reporting to Evidence-Based Action. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2018, 12, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan Ramirez, L.; Baker, E.; Metzler, M. Promoting Health Equity: A Resource to Help Communities Address Social Determinants of Health; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2008.

- Turin, T.C.; Rashid, R.; Ferdous, M.; Chowdhury, N.; Naeem, I.; Rumana, N.; Rahman, A.; Rahman, N.; Lasker, M. Perceived Challenges and Unmet Primary Care Access Needs among Bangladeshi Immigrant Women in Canada. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720952618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, R.R.; Smith, R.N.; Fowler, K.J.; Gates, J.; Jefferson, N.M.; Adler, J.T.; Patzer, R.E. Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR): An Underutilized Approach to Address Surgical Disparities. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health M, and Social Services; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities After Disasters: Strategies, Opportunities, and Planning for Recovery; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Coombe, C.M.; Schulz, A.J.; Brakefield-Caldwell, W.; Gray, C.; Guzman, J.R.; Kieffer, E.C.; Lewis, T.; Reyes, A.G.; Rowe, Z.; Israel, B.A. Applying Experiential Action Learning Pedagogy to an Intensive Course to Enhance Capacity to Conduct Community-Based Participatory Research. Pedagog. Health Promot. 2020, 6, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, S. To Achieve Vaccine Equity, “CEAL” Examines Barriers to Vaccination; On the Pulse; Johns Hopkins Nursing: Baltmore, MD, USA, 2021; Available online: https://magazine.nursing.jhu.edu/2021/08/to-achieve-vaccine-equity-ceal-examines-barriers-to-vaccination/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

| Clifton-Berea | Greenmount East | Madison/ East End | Oldtown/ Middle East | Baltimore City | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience in Baltimore (Entrepreneurship) | |||||

| 47 % of Small Black-Owned Businesses | |||||

| Total Population | 8413 | 7691 | 7204 | 9285 | 622,454 |

| Education | |||||

| % Adults with High School Diploma or less | 63.3 | 66.7 | 72.0 | 68.1 | 47.2 |

| % Adults with College Degree or more | 7.7 | 8.2 | 6.3 | 15.0 | 28.7 |

| Socioeconomic Environment | |||||

| Median Household Income | $25,738 | $23,277 | $27,454 | $14,105 | 41,819 |

| % Income < $25,000 | 44.8 | 52.4 | 48.3 | 66.5 | 32.2 |

| % Unemployment Rate | 17.4 | 24.7 | 26.4 | 20.7 | 13.1 |

| % Family Living in Poverty | 30.2 | 33.8 | 45.2 | 60.0 | 28.8 |

| Health Care Insurance | |||||

| % Adults without Insurance | 10.0 | 12.2 | 15.5 | 13.2 | 11.7 |

| % Children without Insurance | 3.4 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 4.4 |

| Life Expectancy at Birth (years) | 66.9 | 67.9 | 68.9 | 70.4 | 73.6 |

| Top Leading Causes of Mortality # | |||||

| Heart Disease | 27.7 | 42.3 | 41.2 | 35.3 | 24.4 |

| Cancer (all types) | 24.9 | 37.6 | 44.7 | 30.5 | 21.2 |

| Stroke | 6.9 | 7.0 | 12.7 | 5.1 | 5.0 |

| Diabetes | 2.8 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.0 |

| HIV | 2.7 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Drug- and/or Alcohol-Induced | 8.3 | 8.1 | 6.9 | 8.4 | 4.4 |

| Homicide | 10.4 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| |||||

| Barriers and Challenges Organizations Currently Face | Issues | Solutions | Example Quotations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Capacity defined as mission, vision, services, initiatives, capacity, sustainability, and funding | “historically not had access” | “Morgan CARES meeting space provides an opportunity for individuals to connect with others” | “I was wondering what’s the mechanism that you are thinking about for making that real and for making sure that people are even aware that there are some people who are going to be in the know and have access to, but, but then there are others might not know that this opportunity exits?” |

| “Sustainability” | “funding opportunities” | “Hard to sustain because it is very expensive.” | |

| “technological gap” “how to sustain data collection” | “leadership training” | “We have people within the community that are resident researchers that are currently right now going into the community to figure out the needs and getting data and really making sure that the data we are gathering is what the community wants. But we are trying to figure out how to sustain that data.” |

| Stage | Activities | Sessions | Attendees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection & Partnership Development | Outreach, Networking, Information Sessions, Linkage, Matchmaking, Introduction Training | 83 | 406 |

| Innovation | Orientation, Technical Assistance, Partner Consultation | 65 | 244 |

| Collaborative Actions | Skills Training & workshops, Project management support | 23 | 205 |

| Outcome & Impact | Project Evaluation, Consultation with experts, Dissemination Support | 16 | 114 |

| Project Title | Principal Investigators (Community—Academic Partnerships) | Initiative |

|---|---|---|

| STOP-OD: Prevent Deaths from Opioid Overdose | Haygood, J. (Applications Operation, LLC)—Estreet, A. (MSU, Social Work) | Mobile app for community health workers and family members to access resources and alert first responders in cases of potential OD’s |

| Safer Schools | Gordon, S. (Cool Green Schools)— Gibson, S. (MSU, Education and Urban Studies) | COVID hygiene and cleanliness educational materials for students in preparation for returning to in-person learning |

| Purple Light Project | Najee Ullah, M. (FullBlast STEAM)— Lewis J., Balraj, D., Ekpew, A. (MSU, P.I.s) | Testing UV light as a germicide on high-touch surfaces |

| Mid-Day Check In | Smith, D. (SolFlowers)— Holland, J. (MSU, Family and Consumer Sciences) | Talking sessions about mental health, wellness, nutrition over a healthy meal |

| Ivanhoe Valley Garden | Govan, N. (Wilson Park Northern Neighborhood Assoc)—Holms, K. (MSU, P.I.) | Beautifying neighborhood lot for neighbors to grow healthy foods, trying to establish a long-term program for volunteers to tend to the plots |

| Food Life Series | White, A. (I AM Whole, Inc., Baltimore, MD, USA.)— Brown, E. and Peterson, J. (MSU, Nutritional Science) | Developing educational sessions to help MSU students become food secure, and avoid becoming food insecure in the future |

| ECBB Emergency Preparedness Program | North, J. (Empowering Communities Block by Block)—Rowel, R. (MSU, P.I.) | Assessing the feasibility of using the community walk through theatre as a means of delivering emergency preparedness and health communications to neighborhood residents |

| Older Women Embracing Life (OWEL) | Richards, G. (OWEL)— Weaks, F. (MSU, Health Science) | A storytelling film about the oldest cohort of women living with HIV/AIDS in Baltimore City |

| The MD Healthy Workplace Task Force | Glover-Kerkvliet, J. (Baltimore Job Hunters Support Group)—Page, R. (MSU, P.I.) | To develop an 8-week training on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of workplace bullying and mobbing |

| Dyslexia Awareness Campaign | Winston, W. (So All Can Read)— Gibson, S. (MSU, Teacher Education and Professional Development) | Spread dyslexia awareness, educate parents, remove stigma, and reduce financial burden. |

| Educational x Tech Training Program (EDxTech) | Best, A. (Baltimore Tech Hub)— Wright, M. (MSU, P.I.) | Provide educational resources within communities while using tech to elevate understanding |

| Cherry Hill Food System Assessment | Jackson, E. (Black Yield Institute)— Walker, K. (MSU, P.I.) | To address unequal distribution of land and food access by surveying Cherry Hill residents’ perceptions of the food system as food apartheid |

| #JustDont: Youth Anti-Litter and Art Advocacy Movement | Delgado, C. and Sharif, N. (Tola’s Room)— DePaolo, B. (MSU, Fine Arts) | Pilot project to activate conversations and action around creating "litter free zones" in the Belair-Edison community |

| Light Within the Margins | Garcia, M. (Light Within (& CWTT))— Reeder, (MSU, Visual Arts) | To address the impact of ACES primarily through trauma informed creative workshops and storytelling |

| CAMMRAD Police App | Doswell, J. (Juxtopic)— Sinclair, M. (MSU, Social Work) | To eradicate the endemic of police violence against African American males in Baltimore, MD |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheikhattari, P.; Shaffer, E.; Barsha, R.A.A.; Silver, G.B.; Elliott, B.; Delgado, C.; Purviance, P.; Odero-Marah, V.; Bronner, Y. Building Capacity for Community-Academia Research Partnerships by Establishing a Physical Infrastructure for Community Engagement: Morgan CARES. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912467

Sheikhattari P, Shaffer E, Barsha RAA, Silver GB, Elliott B, Delgado C, Purviance P, Odero-Marah V, Bronner Y. Building Capacity for Community-Academia Research Partnerships by Establishing a Physical Infrastructure for Community Engagement: Morgan CARES. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912467

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheikhattari, Payam, Emma Shaffer, Rifath Ara Alam Barsha, Gillian Beth Silver, Bethtrice Elliott, Christina Delgado, Paula Purviance, Valerie Odero-Marah, and Yvonne Bronner. 2022. "Building Capacity for Community-Academia Research Partnerships by Establishing a Physical Infrastructure for Community Engagement: Morgan CARES" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912467

APA StyleSheikhattari, P., Shaffer, E., Barsha, R. A. A., Silver, G. B., Elliott, B., Delgado, C., Purviance, P., Odero-Marah, V., & Bronner, Y. (2022). Building Capacity for Community-Academia Research Partnerships by Establishing a Physical Infrastructure for Community Engagement: Morgan CARES. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912467