Using Concept Mapping to Define Indigenous Housing First in Hamilton, Ontario

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Approach and Governance

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Concept Mapping Activities

2.3.1. Brainstorming

“Delivering Housing Services involves the following component or service…”

2.3.2. Sorting and Rating

2.3.3. Map Interpretation Session

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

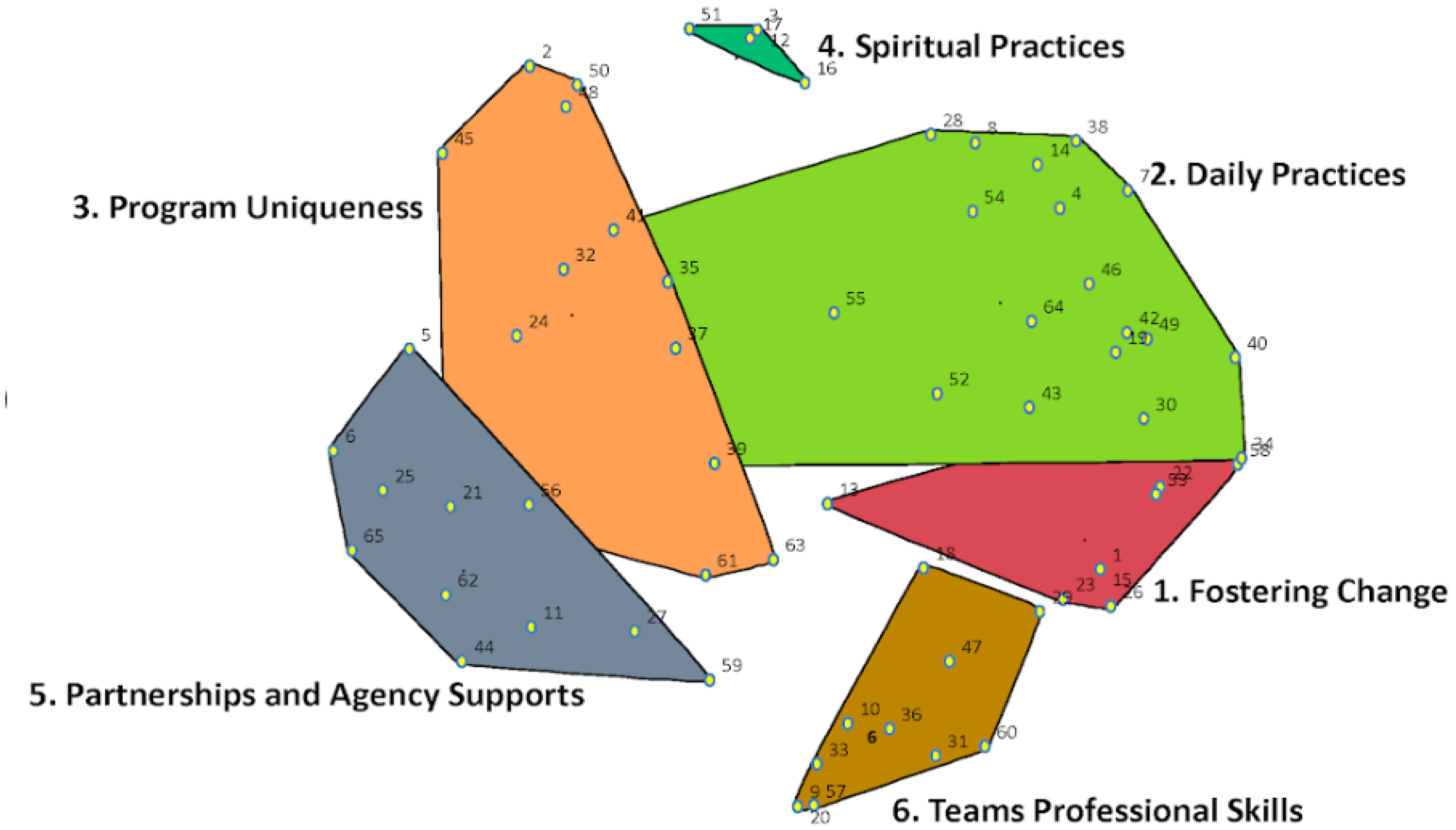

3.2. Cluster Map

3.2.1. Fostering Change

3.2.2. Daily Practices

3.2.3. Program Uniqueness

3.2.4. Spiritual Practices

3.2.5. Partnership and Agency Supports

3.2.6. Team’s Professional Skills

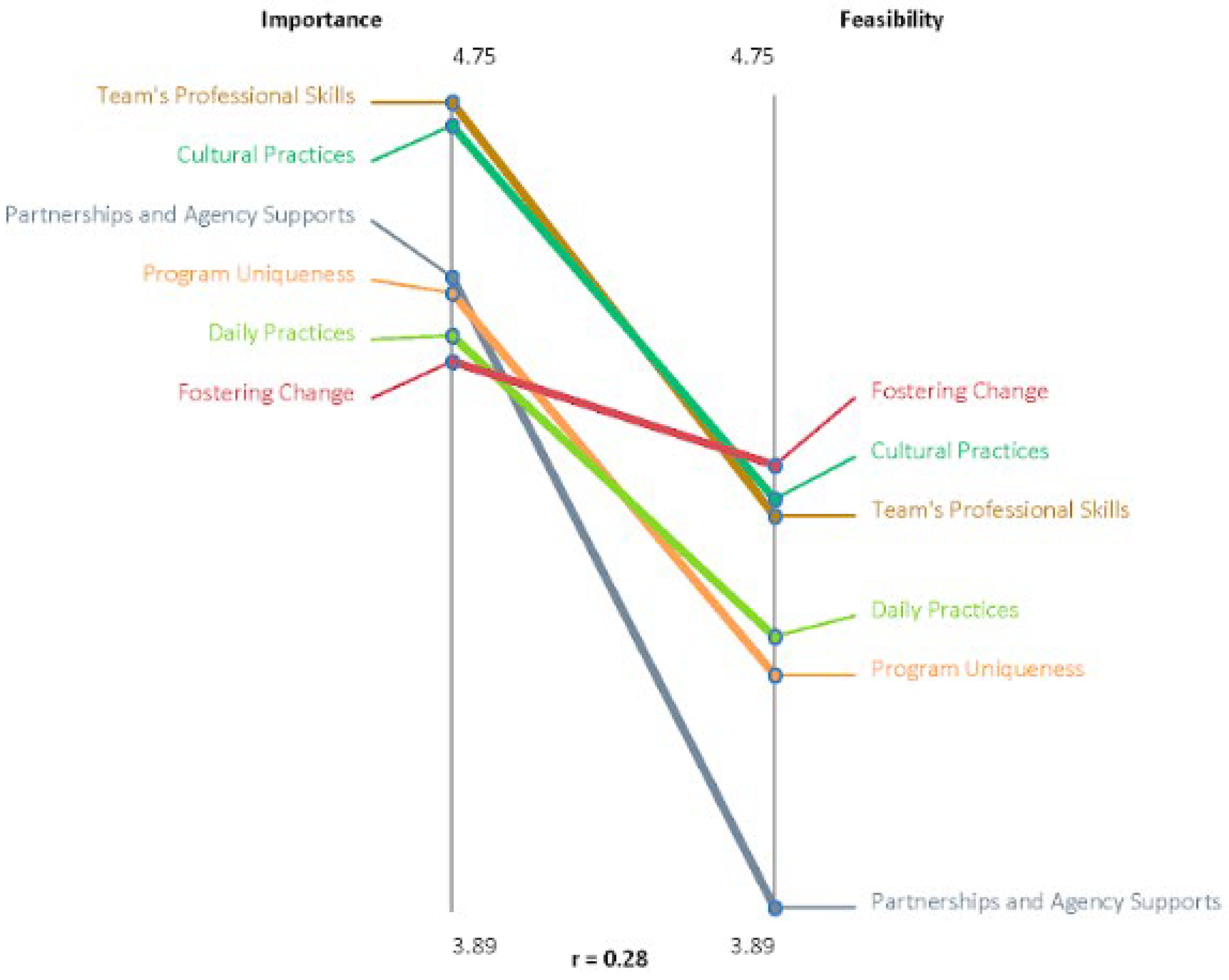

3.3. Cluster and Statement Ratings

3.4. Pattern Matches

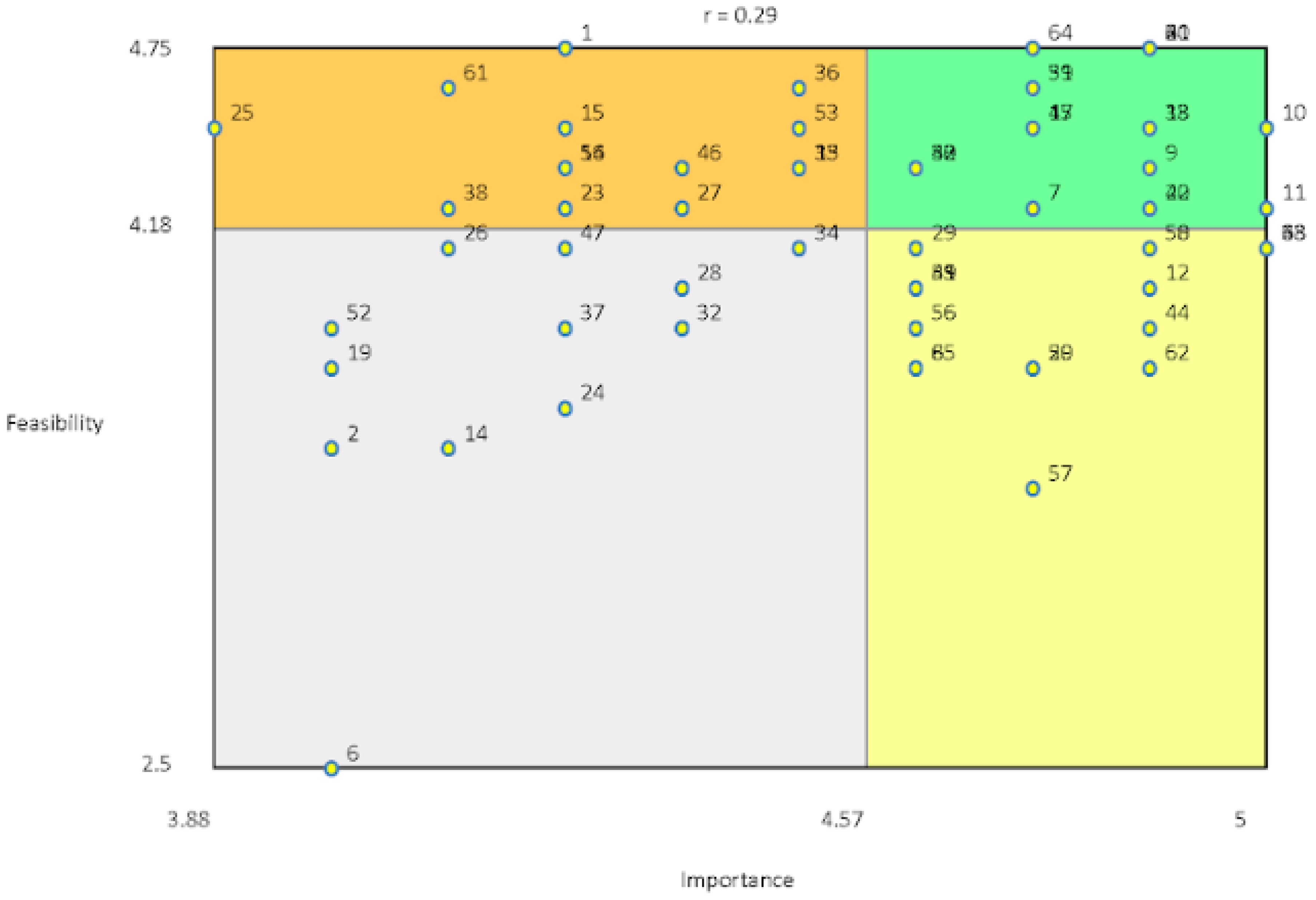

3.5. Go Zone Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rotondi, M.A.; O’Campo, P.; O’Brien, K.; Firestone, M.; Wolfe, S.H.; Bourgeois, C.; Smylie, J.K. Our Health Counts Toronto: Using Respondent-Driven Sampling to Unmask Census Undercounts of an Urban Indigenous Population in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanger, Y.; Awosoga, O.; Head, G. Homelessness, Urban Aboriginal People, and the Need for a National Enumeration. Aborig. Policy Stud. 2013, 2, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; Spiller, M.; O’Campo, P. Unmasking Health Determinants and Health Outcomes for Urban First Nations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monette, L.; Rourke, S.B.; Tucker, R.; Greene, S.; Sobota, M.; Koornstra, J.; Byers, S.; Ahluwalia, A.; Bekele, T.; Bacon, J.; et al. Housing Status and Health Outcomes in Aboriginal People Living with HIV/AIDS in Ontario: The Positive Spaces, Healthy Places Study. Can. J. Aborig. Community-Based HIV Res. 2009, 2, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R. Aboriginal Self-Determination and Social Housing in Urban Canada: A Story of Convergence and Divergence. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Stergiopoulos, V.; O’Campo, P.; Gozdik, A. Ending Homelessness among People with Mental Illness: The At Home/Chez Soi Randomized Trial of a Housing First Intervention in Toronto. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiopoulos, V.; Hwang, S.; Gozdzik, A.; Nisenbaum, R.; Latimer, E.; Rabouin, D.; Adair, C.; Bourque, J.; Connelly, J.; Frankish, J.; et al. Effect of Scattered-Site Housing Using Rent Supplements and Intensive Case Management on Housing Stability among Homeless Adults with Mental Illness: A Randomized Trial. JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2015, 313, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Evaluation of the Homelessness Partnering Strategy; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018.

- Thistle, J.A. Definition of Indigenous Homelessness in Canada; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil, G.; Wilson, K. Reconciling Indigenous Need with the Urban Welfare State? Evidence of Culturally-Appropriate Services and Spaces for Aboriginals in Winnipeg, Canada. Geoforum 2010, 41, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; Smylie, J.; Maracle, S.; Siedule, C.; De dwa da dehs nye>s Aboriginal Health Access Centre; Métis Nation of Ontario; O’Campo, P. Concept Mapping: Application of a Community-Based Methodology in Three Urban Aboriginal Populations. Am. Indian Cult. Res. J. 2014, 38, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W. An Introduction to Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Eval. Program Plann. 1989, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; O’Campo, P.; Peak, G.; Gielen, A.; McDonnell, K.; Trochim, W. An Introduction to Concept Mapping as a Participatory Public Health Research Method. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1392–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, M.; Trochim, W. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781412940276. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, M.; Poole, N.; Shea, B.; Gone, J.P.; Mykota, D.; Farag, M.; Hall, C.H.; Mushquash, C.; Dell, C. Cultural Interventions to Treat Addictions in Indigenous Populations: Findings from a Scoping Study. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2014, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.P.; Cote, W. Cultural Connectedness Protects Mental Health against the Effect of Historical Trauma among Anishinabe Young Adults. Public Health 2019, 176, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gone, J.P. Redressing First Nations Historical Trauma: Theorizing Mechanisms for Indigenous Culture as Mental Health Treatment. Transcult. Psychiatry 2013, 50, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distasio, J.; Zell, S.; McCullough, S.; Edel, B. Localized Approaches to Ending Homelessness: Indigenizing Housing First; Institute of Urban Studies: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Housing Caucus Working Group and Canadian Housing Renewal Association (CHRA). An Urban, Rural and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy for Canada: Proposed Governance Structure for the for Indigenous by Indigenous (FIBI); Indigenous Housing Caucus Working Group: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Cluster | Statement | Average Feasibility Rating | Average Importance Rating | Feasibility Rating | Importance Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fostering Change | 4.36 | 4.47 | High | Low | ||

| Supporting clients’ goals by meeting them where they are at | 1 | Facilitating sobriety groups for clients | 4.75 | 4.25 | High | Low |

| 13 | Program focuses on building and providing a circle of care for clients | 4.38 | 4.50 | High | Low | |

| 15 | Program provides support groups using a recovery framework | 4.50 | 4.25 | High | Low | |

| 22 | Working on client goals at their own pace | 4.25 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 23 | Program provides clients and community with regular drop-ins with food, clothing, toiletries (e.g., weekly breakfast, daily life skills) | 4.25 | 4.25 | High | Low | |

| 26 | Staff de-escalate and support clients in crisis | 4.13 | 4.13 | Low | Low | |

| 30 | Staff honouring lives and gifts of clients | 4.38 | 4.63 | High | High | |

| 53 | Staff help clients to develop a toolbox with coping strategies, support, and resources | 4.50 | 4.50 | High | Low | |

| 58 | Staff supporting client self-image and growth once housed | 4.13 | 4.88 | Low | High | |

| 2. Daily Practices | 4.18 | 4.50 | Low | Low | ||

| Broad range of program activities delivered by staff | 4 | Staff advocating to landlords on behalf of clients (e.g., arrears concerns, eviction notices) | 4.75 | 4.88 | High | High |

| 7 | Staff make referrals to services within DAHAC | 4.25 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 8 | Staff providing home healthcare visits | 3.75 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 14 | Staff mentor clients to support them in giving back to community | 3.50 | 4.13 | Low | Low | |

| 19 | Staff accompanying clients to appointments (hospitals, social services, etc.) | 3.75 | 4.00 | Low | Low | |

| 28 | Rapid rehousing for clients that have been evicted | 4.00 | 4.38 | Low | Low | |

| 34 | Staff following through in every aspect of case plan (e.g., follow-up with referrals) | 4.13 | 4.50 | Low | Low | |

| 38 | Staff assist clients to get identification documents | 4.25 | 4.13 | High | Low | |

| 39 | Program provides external referrals (e.g., medical, addictions, 24/7 supports) | 4.63 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 40 | Staff having monthly interactions with clients | 4.25 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 41 | Program provides housing allotments to clients | 4.00 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 42 | Staff case plan with clients (i.e., assessments and safety planning) | 4.38 | 4.63 | High | High | |

| 43 | Program provides services and support in addition to housing | 4.38 | 4.63 | High | High | |

| 46 | Staff addressing food insecurity for clients (e.g., relationships with food banks, groceries) | 4.38 | 4.38 | High | Low | |

| 49 | Staff checking in through client housing transitions and on future housing needs | 4.00 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 52 | Program providing harm reduction supplies and supports | 3.88 | 4.00 | Low | Low | |

| 54 | Completing applications for income supports | 4.38 | 4.25 | High | Low | |

| 55 | Program hosts special events that don’t centre around alcohol/drugs (i.e., birthdays, holidays) | 4.00 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 64 | Program provides clients with start-up packages/welcome baskets with bedding | 4.75 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 3. Program Uniqueness | 4.14 | 4.55 | Low | Low | ||

| Supporting specific experiences and needs of Indigenous population experiencing homelessness | 2 | Opening services to broader Indigenous community | 3.50 | 4.00 | Low | Low |

| 21 | Program accepts referrals from all sources, family, community, and By-Name list | 4.75 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 24 | Program offering different housing options (e.g., rooming house pilot) | 3.63 | 4.25 | Low | Low | |

| 32 | Providing health services and education in community settings (e.g., medical supplies, drop-in clinic) | 3.88 | 4.38 | Low | Low | |

| 35 | Staff conduct outreach activities with Indigenous homeless population sleeping outdoors | 4.38 | 4.50 | High | Low | |

| 37 | Program supports clients that are ineligible for Housing First service (healthcare connections, service referrals, material needs) | 3.88 | 4.25 | Low | Low | |

| 45 | Holistic approach to working with clients that includes mind, body, and spirit | 4.50 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 48 | Creating a culturally safe environment for clients in every interaction and space | 4.13 | 5.00 | Low | High | |

| 50 | Re-establishing connection to Indigenous community for clients | 4.13 | 4.88 | Low | High | |

| 61 | Staff provide meals at programs | 4.63 | 4.13 | High | Low | |

| 63 | During intake, not relying only on acuity and focusing on stories | 4.13 | 5.00 | Low | High | |

| 4. Cultural Practices | 4.33 | 4.73 | High | High | ||

| Program provides access to local Indigenous practices and knowledge | 3 | Program provides access to traditional culture for clients (e.g., providing teachings) | 4.13 | 5.00 | Low | High |

| 12 | Program re-establishes connection to Indigenous community for clients | 4.00 | 4.88 | Low | High | |

| 16 | Staff provide smudging in clients’ homes | 4.38 | 4.25 | High | Low | |

| 17 | Program housed within an agency that offers services from waters of life to returning to the spirit world | 4.50 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 51 | Program housed within organization that has traditional healers | 4.63 | 4.75 | High | High | |

| 5. Partnerships and Agency Supports | 3.89 | 4.56 | Low | Low | ||

| Accountable and trusting relationships both internally and externally are essential to meeting client needs | 5 | Staff build and manage trusting landlord relationships | 4.38 | 4.63 | High | High |

| 6 | Program partners with Ontario Aboriginal Housing for supportive housing | 2.50 | 4.00 | Low | Low | |

| 11 | Program ensures accountability between staff and clients and vice versa | 4.25 | 5.00 | High | High | |

| 25 | Program housed within a health access centre | 4.50 | 3.88 | High | Low | |

| 27 | Program builds in flexible funding to respond to client needs (i.e., medical supplies, for client units) | 4.25 | 4.38 | High | Low | |

| 44 | Team lead and senior management understanding and supporting all staff roles | 3.88 | 4.88 | Low | High | |

| 56 | Program provides a smooth transfer from intake to case manager | 3.88 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 59 | Program aware and responsive to needs of community | 3.75 | 4.75 | Low | High | |

| 62 | Program has support from all levels of DAHAC management to address bureaucratic barriers | 3.75 | 4.88 | Low | High | |

| 65 | Team lead mitigating and managing partnerships with external groups (landlords, Ontario Aboriginal Housing) | 3.75 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 6. Team’s Professional Skills | 4.31 | 4.75 | High | High | ||

| Program creates space for staff to self-reflect, role model and engage in self-care | 9 | Staff recognizing and drawing boundaries with clients | 4.38 | 4.88 | High | High |

| 10 | Program operating from stance of hope and strengths | 4.50 | 5.00 | High | High | |

| 18 | Staff advocating for clients (i.e., shelter access, hospital care, CTOs, basic rights) | 4.50 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 20 | Staff self-reflecting on their biases in client relationships | 3.75 | 4.75 | Low | High | |

| 29 | Managing and setting client expectations of program at intake | 4.13 | 4.63 | Low | High | |

| 31 | Empathetic staff | 4.75 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 33 | Program consists of a supportive, close, and trusting team | 4.50 | 4.88 | High | High | |

| 36 | Program’s approach is inclusive of clients’ full identities (i.e., sexual identity/gender/culture) | 4.63 | 4.50 | High | Low | |

| 47 | Prioritizing client choice in housing search (location, housing type, roommates, etc.) | 4.13 | 4.25 | Low | Low | |

| 57 | Staff engage in self-care | 3.38 | 4.75 | Low | High | |

| 60 | Staff provides positive role modelling | 4.75 | 4.88 | High | High | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Firestone, M.; Zewge-Abubaker, N.; Salmon, C.; McKnight, C.; Hwang, S.W. Using Concept Mapping to Define Indigenous Housing First in Hamilton, Ontario. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912374

Firestone M, Zewge-Abubaker N, Salmon C, McKnight C, Hwang SW. Using Concept Mapping to Define Indigenous Housing First in Hamilton, Ontario. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912374

Chicago/Turabian StyleFirestone, Michelle, Nishan Zewge-Abubaker, Christina Salmon, Constance McKnight, and Stephen W. Hwang. 2022. "Using Concept Mapping to Define Indigenous Housing First in Hamilton, Ontario" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912374

APA StyleFirestone, M., Zewge-Abubaker, N., Salmon, C., McKnight, C., & Hwang, S. W. (2022). Using Concept Mapping to Define Indigenous Housing First in Hamilton, Ontario. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912374