Gender Transformative Interventions for Perinatal Mental Health in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

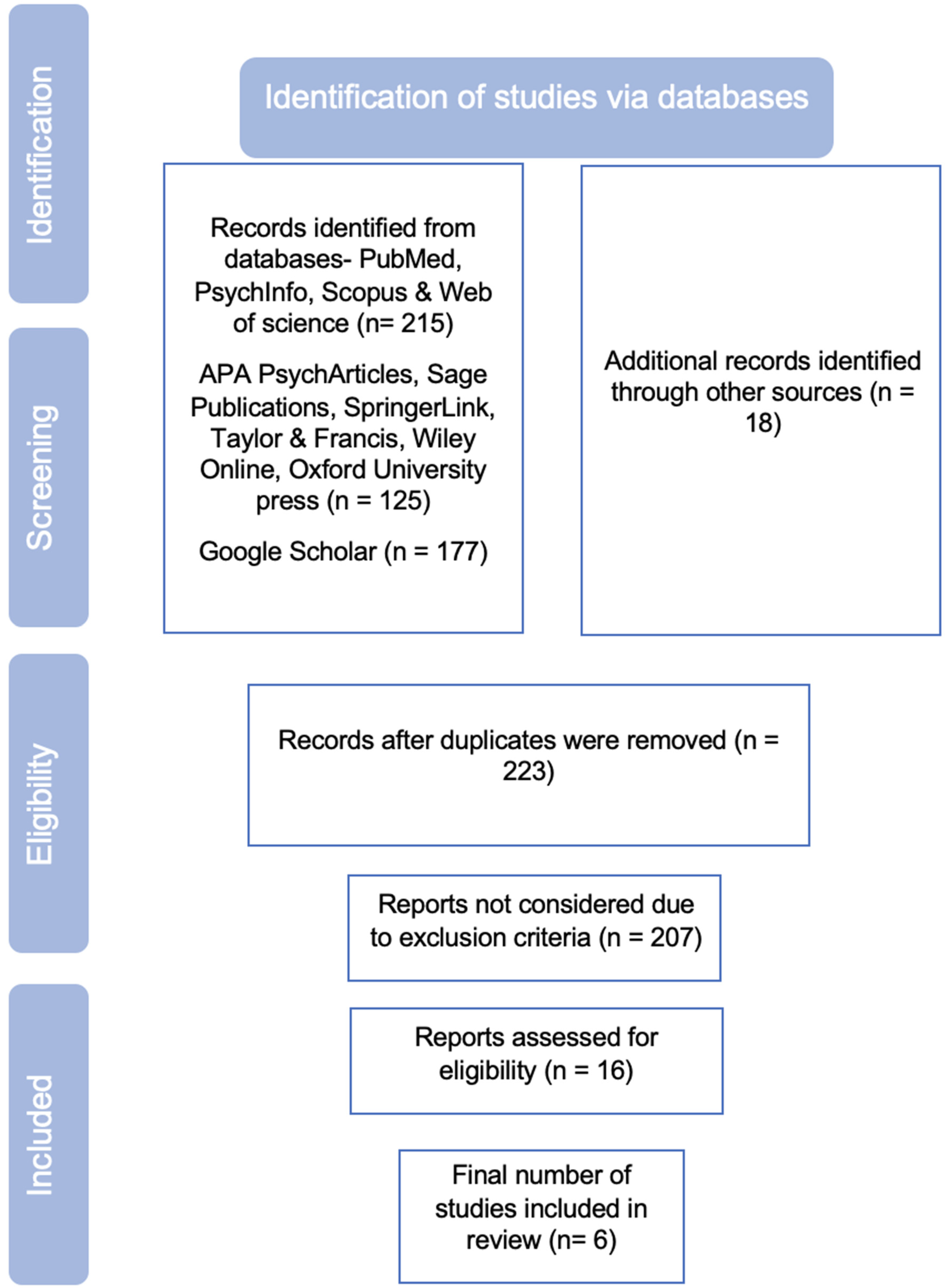

2. Method

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection (Inclusion and Exclusion)

- Published in English

- Programs designed and implemented in LMIC countries.

- Studies having any one of the three mental health outcomes in the perinatal period which include

- a.

- Improvement in social support or better relationship with partner;

- b.

- Decrease in depression, anxiety or any Common Mental Disorder;

- c.

- Decrease in Domestic violence or Intimate Partner Violence.

- Any study design—RCTs, Non Randomised Controlled studies, Case Control studies, pre post intervention studies.

- Publication years 2007–2022.

- Study location not in LMIC.

- Studies not relating to perinatal period.

- Studies not relating to mental health or risk.

- Studies not relating to maternal mental health.

2.4. Charting the Data

2.5. Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Article Characteristics

3.2. Program Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, J.; Goodman, J. Comparative effects of antidepressant medications and untreated major depression on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiva, L.; Desai, G.; Satyanarayana, V.A.; Venkataram, P.; Chandra, P.S. Negative Childbirth Experience and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder-A Study Among Postpartum Women in South India. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 640014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huschke, S.; Murphy-Tighe, S.; Barry, M. Perinatal mental health in Ireland: A scoping review. Midwifery 2020, 89, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, E.J.; Fairbrother, N.; Cox, M.L.; White, I.R.; Fawcett, J.M. The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C.V.; Santos, T.M.; Devries, K.; Knaul, F.; Bustreo, F.; Gatuguta, A.; Houvessou, G.M.; Barros, A. Identifying the women most vulnerable to intimate partner violence: A decision tree analysis from 48 low and middle-income countries. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 42, 101214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachani, S.; Sahoo, S.M.; Nagendrappa, S.; Dabral, A.; Chandra, P. Anxiety and depression among women with COVID-19 infection during childbirth—Experience from a tertiary care academic center. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2022, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNab, S.E.; Dryer, S.L.; Fitzgerald, L.; Gomez, P.; Bhatti, A.M.; Kenyi, E.; Somji, A.; Khadka, N.; Stalls, S. The silent burden: A landscape analysis of common perinatal mental disorders in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, N.; Beard, J.; Mesic, A.; Patel, A.; Henderson, D.; Hibberd, P. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and perinatal mental disorders in low and lower middle income countries: A systematic review of literature, 1990–2017. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.A.; Chan, G.; McCarthy, K.J.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. Psychological and physical intimate partner violence and young children’s mental health: The role of maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms and parenting behaviors. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 77, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, J.; Bhandari, T.R. Associated Factors of Postpartum Depression in Women Attending a Hospital in Pokhara Metropolitan, Nepal. Indian J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2019, 6, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Rodrigues, M.; DeSouza, N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atif, N.; Krishna, R.N.; Sikander, S.; Lazarus, A.; Nisar, A.; Ahmad, I.; Raman, R.; Fuhr, D.C.; Patel, V.; Rahman, A. Mother-to-mother therapy in India and Pakistan: Adaptation and feasibility evaluation of the peer-delivered Thinking Healthy Programme. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhananga, P.; Mali, P.; Poudel, L.; Gurung, M. Prevalence of Postpartum Depression in a Tertiary Health Care. JNMA J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2020, 58, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, T.; Garg, P.; Akhtar, F.; Mehra, S. Association between gender disadvantage factors and postnatal psychological distress among young women: A community-based study in rural India. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insan, N.; Weke, A.; Forrest, S.; Rankin, J. Social determinants of antenatal depression and anxiety among women in South Asia: A systematic review & meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263760. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Creed, F. Outcome of prenatal depression and risk factors associated with persistence in the first postnatal year: Prospective study from Rawalpindi, Pakistan. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 100, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Nair, N.; Tripathy, P.K.; Barnett, S.; Rath, S.; Mahapatra, R.; Gope, R.; Bajpai, A.; Sinha, R.; Prost, A. Explaining the impact of a women’s group led community mobilisation intervention on maternal and newborn health outcomes: The Ekjut trial process evaluation. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2010, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jat, T.R.; Deo, P.R.; Goicolea, I.; Hurtig, A.K.; Sebastian, M.S. Socio-cultural and service delivery dimensions of maternal mortality in rural central India: A qualitative exploration using a human rights lens. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 24976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Bloom, S.; Brodish, P. Gender equality as a means to improve maternal and child health in Africa. Health Care Women Int. 2015, 36, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha, G.T.; Acharya, M.S. Trajectory of perinatal mental health in India. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 2019, 35, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Ghule, M.; Ritter, J.; Battala, M.; Gajanan, V.; Nair, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Silverman, J.G.; Balaiah, D.; Saggurti, N. Cluster randomized controlled trial evaluation of a gender equity and family planning intervention for married men and couples in rural India. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.; McKague, K.; Musoke, J. Gender Intentional Strategies to Enhance Health Social Enterprises in Africa: A toolkit; Bluefish Publishing: Burgess Hill, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, J.M.; Wilkins, K.G.; Morales, G.J.; Widyono, M.; Middlestadt, S.E. An evidence review of gender-integrated interventions in reproductive and maternal-child health. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19 (Suppl. S1), 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.E.; Levack, A. Synchronizing Gender Strategies: A Cooperative Model for Improving Reproductive Health and Transforming Gender Relations; Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, U.; Jaiprakash, B.; Haitsuka, H.; Kim, S. One year into the pandemic: A systematic review of perinatal mental health outcomes during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 674194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, W.J.; Erickson, M.F.; LaRossa, R. An intervention to increase father involvement and skills with infants during the transition to parenthood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Chandramohan, S.; Sundaravathanam, N.; Rajasekaran, A.B.; Sekhar, R. Father involvement in early childhood care: Insights from a MEL system in a behavior change intervention among rural Indian parents. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.L.; Wahler, R.G. Are mindful parents more authoritative and less authoritarian? An analysis of clinic-referred mothers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, S.L.; Fleming, P.J.; Colvin, C.J. The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17 (Suppl. S2), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Ashby, C.; Quandt, M.; Halsey, E.; Nagar, A.; Greene, M.E. Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e225–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, H.M.; van Mossel, C.; Scott, S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Country Classification. 2022. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Harris, M.W.; Barnett, T.; Bridgman, H. Rural Art Roadshow: A travelling art exhibition to promote mental health in rural and remote communities. Arts Health 2018, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Society for the Study of Human Biology, SSHB. Low or Middle Income Country LMIC. 2022. Available online: https://www.sshb.org/lmic/# (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Powell, N.; Dalton, H.; Perkins, D.; Considine, R.; Hughes, S.; Osborne, S.; Buss, R. Our healthy Clarence: A community-driven wellbeing initiative. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruane-McAteer, E.; Gillespie, K.; Amin, A.; Aventin, Á.; Robinson, M.; Hanratty, J.; Khosla, R.; Lohan, M. Gender-transformative programming with men and boys to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights: A systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhya, K.G.; Haberland, N.; Das, A.; Ram, F.; Sinha, R.K.; Ram, U.; Mohanty, S.K. Empowering Married Young Women and Improving Their Sexual and Reproductive Health: Effects of the First-Time Parents Project. 2008. Available online: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1234&context=departments_sbsr-pgy (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Comrie-Thomson, L.; Tokhi, M.; Ampt, F.; Portela, A.; Chersich, M.; Khanna, R.; Luchters, S. Challenging gender inequity through male involvement in maternal and newborn health: Critical assessment of an emerging evidence base. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17 (Suppl. S2), 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yore, J.; Dasgupta, A.; Ghule, M.; Battala, M.; Nair, S.; Silverman, J.; Saggurti, N.; Balaiah, D.; Raj, A. CHARM, a gender equity and family planning intervention for men and couples in rural India: Protocol for the cluster randomized controlled trial evaluation. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, K.; Levtov, R.G.; Barker, G.; Bastian, G.G.; Bingenheimer, J.B.; Kazimbaya, S.; Nzabonimpa, A.; Pulerwitz, J.; Sayinzoga, F.; Sharma, V.; et al. Gender-transformative Bandebereho couples’ intervention to promote male engagement in reproductive and maternal health and violence prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapolisi, W.A.; Ferrari, G.; Blampain, C.; Makelele, J.; Kono-Tange, L.; Bisimwa, G.; Merten, S. Impact of a complex gender-transformative intervention on maternal and child health outcomes in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: Protocol of a longitudinal parallel mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrie-Thomson, L.; Webb, K.; Patel, D.; Wata, P.; Kapamurandu, Z.; Mushavi, A.; Nicholas, M.A.; Agius, P.A.; Davis, J.; Luchters, S. Engaging women and men in the gender-synchronised, community-based Mbereko+ Men intervention to improve maternal mental health and perinatal care-seeking in Manicaland, Zimbabwe: A cluster-randomised controlled pragmatic trial. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 04042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, S.; Heise, L. Examining the bi-directional relationship between intimate partner violence and depression: Findings from a longitudinal study among women and men in rural Rwanda. SSM-Ment. Health 2021, 1, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchus, L.J.; Colombini, M.; Contreras Urbina, M.; Howarth, E.; Gardner, F.; Annan, J.; Ashburn, K.; Madrid, B.; Levtov, R.; Watts, C. Exploring opportunities for coordinated responses to intimate partner violence and child maltreatment in low and middle income countries: A scoping review. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22 (Suppl. S1), 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.; Greene, M.E. Involving Everyone in Gender Equality by Synchronizing Gender Strategies. Resource Handbook. 2018. Available online: https://www.prb.org/resources/involving-everyone-in-gender-equality-by-synchronizing-gender-strategies/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Oram, S.; Fisher, H.L.; Minnis, H.; Seedat, S.; Walby, S.; Hegarty, K.; Rouf, K.; Angénieux, C.; Callard, F.; Chandra, P.S.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on intimate partner violence and mental health: Advancing mental health services, research, and policy. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 487–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.; Jain, R. (Eds.) Global Masculinities: Interrogations and Reconstructions; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, D.; Ryan, D.; Smith, J.E. (Eds.) Self-Care Program for Women with Postpartum Depression and Anxiety; BC Women’s Hospital & Health Centre: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.M.; Kaminski, A.M.; McDougall, C.; Kefi, A.S.; Marinda, P.A.; Maliko, M.; Mtonga, J. Gender accommodative versus transformative approaches: A comparative assessment within a post-harvest fish loss reduction intervention. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2020, 24, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Gender and MNCH: A Review of the Evidence. 2020. Available online: https://www.gatesgenderequalitytoolbox.org/wp-content/uploads/BMGF_Gender-MNCH-Report_Hi-Res.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- White, B.K.; Giglia, R.C.; Scott, J.A.; Burns, S.K. How new and expecting fathers engage with an app-based online forum: Qualitative analysis. JMIR mHealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, L.P.; Franzon, A.C.A.; Zaratini, F.S.; Vicentine, F.B.; Barbosa-Júnior, F.; Braga, G.C.; Sanchez, J.A.C.; Oliveira-Ciabati, L.; Andrade, M.S.; Fernandes, M.; et al. PRENACEL partner-use of short message service (SMS) to encourage male involvement in prenatal care: A cluster randomized trial. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Juras, R.; Riley, P.; Chatterji, M.; Sloane, P.; Choi, S.K.; Johns, B. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of a family planning mHealth service on knowledge and use of contraception. Contraception 2017, 95, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowsky, J.; Frost, S.; Hendrick, C.E.; Cruz, F.O.T.; Merajver, S.D. Effects of postpartum mobile phone-based education on maternal and infant health in Ecuador. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 134, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.A.; Ronen, K.; Perrier, T.; DeRenzi, B.; Slyker, J.; Drake, A.L.; Mogaka, D.; Kinuthia, J.; John-Stewart, G. Short message service communication improves exclusive breastfeeding and early postpartum contraception in a low-to middle-income country setting: A randomised trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/No | Author, Year and Country | Target Population and Sample Size | Gender-Transformative Components | Aspect of Male Engagement | Primary Outcomes (With Data if Possible) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Santhya et al., 2008 [41] West Bengal and Gujarat, India | Women (pregnant and post-partum first time mothers), husbands and family members 2115 women | The First Time Parent project targeted young married women and their husbands as well as family members to modify gender norms and support prenatal as well as maternal healthcare behaviours. | Outreach workers interacted with husbands about pregnancy and delivery plans. Husbands received home visits from male outreach workers. |

|

| 2 | Comrie-Thomson, L. et al. (2015) [42] Bangladesh, Tanzania and Zimbabwe | Married men and their wives 237 males and females | Education and outreach were conducted with men’s groups and individual men through designated gender equality champions, peer educators or role models. Dialogue, education and mobilisation were conducted with traditional and religious leaders, who have influence over community beliefs and behaviours. Integrated gender equality and male engagement messages delivered through a wide range of activities including community Theatre for Development (T4D), community radio (in Barguna), and community meetings. | Education and outreach were conducted with men’s groups and individual men through designated gender equality champions, peer educators or role models. |

|

| 3 | Raj et al., 2016 [23] Yore et al., 2016 [43] Maharashtra, India | Married men and their wives 1081 Rural young husbands and their wives | The intervention involved three gender, culture and contextually-tailored family planning and gender equity (FP + GE) counseling sessions. A desk-sized CHARM flipchart was used by village health providers to provide men and couples with pictorial information on family planning options, barriers to family planning use including gender equity-related issues (e.g., son preference), the importance of healthy and shared family planning decision-making, and how to engage in respectful marital communication and interactions (inclusive of no spousal violence in the men’s sessions). | Counseling Husbands to Achieve Reproductive Health and Marital Equity (CHARM) intervention, a multi-session intervention delivered to males alone, but included a session with their wives. |

|

| 4 | Doyle et al., 2018 [44] Rwanda | Expectant/current fathers and their partners (pregnant women) 575 couples and 1123 men | The Bandebereho couples’ intervention engaged men and their partners in participatory, small group sessions of critical reflection and dialogue. In Rwanda, the MenCare+ program was known as Bandebereho, or “role model”, as it aimed to transform norms around masculinity by demonstrating positive models of fatherhood. | Transform norms around masculinity by demonstrating positive models of fatherhood. Sessions addressed: gender and power; fatherhood; couple communication and decision-making; IPV; caregiving; child development; and male engagement in reproductive and maternal health. |

|

| 5 | Bapolisi et al., 2020 [45] Democratic Republic of Congo | Husbands and wives 800 men and women | The “Mawe tatu” program, links Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLA) for women with men-to-men sensitisation to transform gender-inequitable norms and behaviours for the empowerment of women. Comprehensive sexuality education for young people, which includes gender and rights themes, is offered as well. | Developing “positive masculinity” by engaging men, if possible spouses of VSLA’s members, towards women’s rights using a peer-to-peer approach. |

|

| 6 | Comrie-Thomson et al., 2022 [46] Manicaland, Zimbabwe | Women and male co-parents 433 women (Pregnant and post-partum mothers up to 2 years post-pregnancy) and 273 men | Women participated in Participatory learning action (PLA) cycles conducted through monthly one-hour group discussions. Discussions explored MNCH services and home care practices recommended during pregnancy and between zero and two years of age, including services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT). The +Men component was delivered by a trained male OPHID staff member who was also a nurse and midwife with substantial community development experience, targeting men. Men participated in monthly one-hour group discussions. Discussions explored similar health topics to those addressed in women’s groups and the same flip chart was used to present information. | Men participated in monthly one-hour group discussions, facilitated by the male project staff member in men’s workplaces or a central community location. |

|

| S/No | Study Design (Format) | Male Engagement Intervention | Individual/Couple/Group Intervention | Facilitators | Inclusion of Other Family Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Randomised controlled trial | MenCare+ program | Couple based intervention. Men along with their current partners (pregnant wonen) were included. Men alone were invited for 15 sessions and with their partners were invited for 8 sessions. | Sex-matched interviewers from Laterite, who had no involvement in the intervention, conducted the interviews. Community volunteers (local fathers) met with the same group of 12 men/couples on a weekly basis. The volunteers received a two-week training, material support, and refresher training. Local nurses and police officers co-facilitated the sessions on pregnancy, family planning, and local laws, respectively. | No |

| 2 | Cluster randomised controlled trial | CHARM gender-equity (GE) counselling in family planning (FP) services. The intervention involved three gender, culture and contextually-tailored family planning and gender equity (FP + GE) counselling sessions delivered by trained male village health care providers to married men (sessions 1 and 2) and couples (session 3) in a clinical setting. | Couple-based intervention | CHARM providers were allopathic (n = 9) and non-allopathic (n = 13) village health care providers trained over three days on FP counselling, GE and IPV issues, and CHARM implementation. All VHPs in the study villages were male; 22 VHPs were trained for delivery. | No |

| 3 | Qualitative study | Focus-group discussions and in-depth interviews | Men-only counselling Couples counselling | Male community workers engaged in men-only education group sessions. | No |

| 4 | Cluster-randomised, longitudinal intervention study | Positive masculinity groups | Only men peer-to-peer discussion groups | Information not given | No |

| 5 | A cluster-randomised controlled pragmatic trial | +Men component | Only men discussion groups Men and women were assessed separately for baseline scores. | Trained male Public Health Interventions and Development (OPHID) staff members. | No |

| 6 | A quasi-experimental research design | First-time Parents Project | Women-only sessions from female outreach workers. Husbands received home-visits from male outreach workers. | Same-sex facilitators conducted interventions. | Yes. Mothers and mother-in-law were included for home-visit based interventions (family sessions). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raghavan, A.; Satyanarayana, V.A.; Fisher, J.; Ganjekar, S.; Shrivastav, M.; Anand, S.; Sethi, V.; Chandra, P.S. Gender Transformative Interventions for Perinatal Mental Health in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912357

Raghavan A, Satyanarayana VA, Fisher J, Ganjekar S, Shrivastav M, Anand S, Sethi V, Chandra PS. Gender Transformative Interventions for Perinatal Mental Health in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912357

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaghavan, Archana, Veena A. Satyanarayana, Jane Fisher, Sundarnag Ganjekar, Monica Shrivastav, Sarita Anand, Vani Sethi, and Prabha S. Chandra. 2022. "Gender Transformative Interventions for Perinatal Mental Health in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912357

APA StyleRaghavan, A., Satyanarayana, V. A., Fisher, J., Ganjekar, S., Shrivastav, M., Anand, S., Sethi, V., & Chandra, P. S. (2022). Gender Transformative Interventions for Perinatal Mental Health in Low and Middle Income Countries—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912357