Health Conditions and Long Working Hours in Europe: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Sample

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Country Typology

2.3.2. Health Assessment and Workload Characteristics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

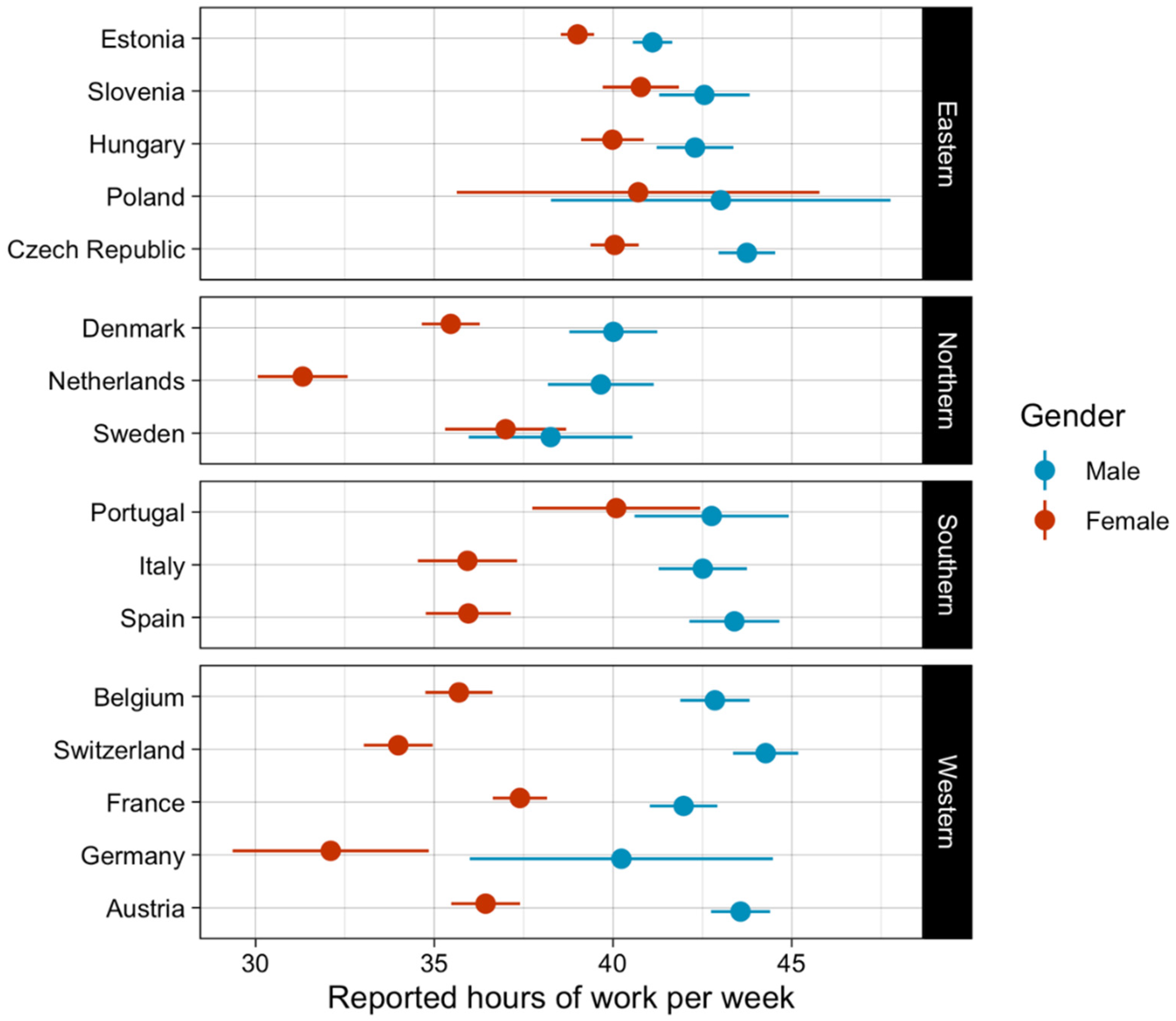

3.1. General Description of the Sample

3.2. Between-Country Differences in Health Conditions by Long Working Hours

3.3. Longitudinal Analysis of Health Outcomes between Healthcare Workers and Workers in Other Industries

4. Discussion

- Association of Reported Health Conditions and Working Hours by Country Groups

- Health Outcomes of Healthcare Workers in Comparison to Other Industries

- Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation; Wolf, J.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Ivanov, I.; Mugdal, S.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing Disease through a Healthier and Safer Workplace; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). The Value of Occupational Safety and Health and the Societal Costs of Work-Related Injuries and Diseases: European Risk Observatory, Literature Review; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Estimating the Costs of Work-Related Accidents and Ill-Health: An analysis of European Data Sources; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. Europeans of Retirement Age: Chronic Diseases and Economic Activity; Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide, I.; Snoeijs, S.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Quattrini, S.; Boerma, W.; Schellevis, F.; Rijken, M. Innovating Care for People with Multiple Chronic Conditions in Europe; Nivel: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A.; Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2012, 9, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Milczarek, M.; Munar, L. Healthy Workers, Thriving Companies—A Practical Guide to Wellbeing at Work: Tackling Psychosocial Risks and Musculoskeletal Disorders in Small Businesses; European Agency for Safety and Health Work: Luxemburg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dayoub, E.; Jena, A.B. Chronic Disease Prevalence and Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors Among, U.S. Health Care Professionals. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1659–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössler, W. Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 262, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. Improving Employment and Working Conditions in Health Services; International Labour Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Griffiths, P.; Dall’Ora, C.; Simon, M.; Ball, J.; Lindqvist, R.; Rafferty, A.M.; Schoonhoven, L.; Tishelman, C.; Aiken, L.H. RN4CAST Consortium. Nurses’ Shift Length and Overtime Working in 12 European Countries. Med. Care 2014, 52, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. 2003. Available online: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32003L0088 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- World Health Organisation. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/global-regional-and-national-burdens-of-ischemic-heart-disease-and-stroke-attributable-to-exposure-to-long-working-hours-for-194-countries-2000-2016 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Eurostat Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Hours_of_work_-_annual_statistics (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Piasna, A. Scheduled to work hard: The relationship between non-standard working hours and work intensity among European workers [2005–2015]. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Bartoll, X.; Basart, H.; Borrell, C. Long working hours and health status among employees in Europe. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2013, 3, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Benavides, F.G.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Bartoll, X.; Vargas, H.; Borrell, C. Long working hours and health in Europe: Gender and welfare state differences in a context of economic crisis. Health Place 2016, 40, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survey of Health. Ageing and Retirement in Europe. SHARE-Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. 2021. Available online: http://www.share-project.org/home0.html (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Börsch-Supan, A.; Brandt, M.; Hunkler, C.; Kneip, T.; Korbmacher, J.; Malter, F.; Schaan, B.; Stuck, S.; Zuber, S. Data Resource Profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe [SHARE]. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Development Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Štiglic, G.; Roger, W.; Cilar, L. R you ready? Using the R programme for statistical analysis and graphics. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 42, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, N.; Kazakiewicz, D.; Wright, F.L.; Timms, A.; Huculeci, R.; Torbica, A.; Gale, C.P.; Achenbach, S.; Weidinger, F.; Vardas, P. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in Europe. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, S.N. What are the effects of psychological stress and physical work on blood lipid profiles? Medicine 2017, 96, e6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangster, D.C.; Rosen, C.C.; Fisher, G.G. Long Working Hours and Well-being: What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Need to Know. J. Bus. Psychol. 2016, 33, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Cardiovascular Diseases [CVDs]. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-[cvds] (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Kivimäki, M.; Kuosma, E.; Ferrie, J.E.; Luukkonen, R.; Nyberg, S.T.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Brunner, E.J.; Fransson, E.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Overweight, obesity, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: Pooled analysis of individual-level data for 120 813 adults from 16 cohort studies from the USA and Europe. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, H.R. The Relation of the Chronic Disease Epidemic to the Health Care Crisis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020, 2, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacionalni inštitut za javno zdravje. Bolezni. 2017. Available online: https://www.nijz.si/sl/17-maj-svetovni-dan-hipertenzije-2017 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Nacionalni inštitut za javno zdravje. Program Skupaj za Zdravje. 2020. Available online: https://www.nijz.si/sl/program-skupaj-za-zdravje (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Ministrstvo za zdravje. Učinkovitost Dela Ambulant Družinske Medicine za Področje Nalog Diplomirane Medicinske Sestre; Ministrstvo za Zdravje: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Waszyk-Nowaczyk, M.; Guzenda, W.; Plewka, B.; Michalak, M.; Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Stryczyński, Ł.; Byliniak, M.; Ratka, A. Screening Services in a Community Pharmacy in Poznan [Poland] to Increase Early Detection of Hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalstra, J.A.; Kunst, A.E.; Borrell, C.; Breeze, E.; Cambois, E.; Costa, G.; Geurts, J.J.M.; Lahelma, E.; Van Oyen, H.; Rasmussen, N.K.; et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: An overview of eight European countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Portugal: Country Health Profile 2017; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Trends in Job Quality in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mion Jr, D.; Pierin, A.M.; Bambirra, A.P.; Assunção, J.H.; Monteiro, J.M.; Chinen, R.Y.; Coser, R.B.; Aikawa, V.N.; Cação, F.M.; Hausen, M.; et al. Hypertension in employees of a University General Hospital. Rev. Do Hosp. Das Clínicas 2004, 59, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, J.; Payandeh, A. Assessing the level of digital health literacy among healthcare workers of teaching hospitals in the southeast of Iran. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 29, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemani, A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia among students and employees in University of Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendy, V.L.; Vargas, R.; Ogungbe, O.; Zhang, L. Hypertension among Mississippi workers by sociodemographic characteristics and occupation, behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Int. J. Hyperten 2020, 2020, 2401747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guariguata, L.; de Beer, I.; Hough, R.; Bindels, E.; Weimers-Maasdorp, D.; Feeley, F.G.; Rinke de Wit, T.F. Diabetes, HIV and other health determinants associated with absenteeism among formal sector workers in Namibia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, R.; McNeil, A.; Sagner, M.; Hills, A.P. The Current Global State of Key Lifestyle Characteristics: Health and Economic Implications. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 59, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korošec, D.; Vrbnjak, D.; Štiglic, G. Health Conditions and Long Working Hours in Europe: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912325

Korošec D, Vrbnjak D, Štiglic G. Health Conditions and Long Working Hours in Europe: A Retrospective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912325

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorošec, Darja, Dominika Vrbnjak, and Gregor Štiglic. 2022. "Health Conditions and Long Working Hours in Europe: A Retrospective Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912325

APA StyleKorošec, D., Vrbnjak, D., & Štiglic, G. (2022). Health Conditions and Long Working Hours in Europe: A Retrospective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912325