COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness in Four Asian Countries: A Comparative Study including Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

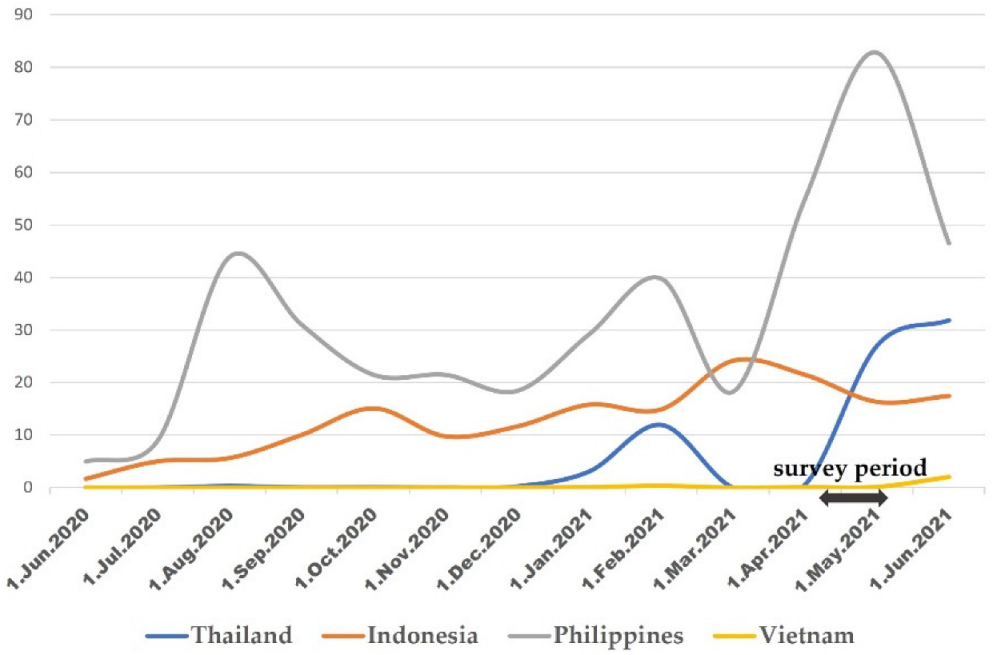

2. Materials and Methods

- Risk perception of the COVID-19 pandemic. The items were subdivided into three components: (a) Confidence in knowledge, (b) Concerns about health risk, and (c) Concerns about economic well-being. Questions were answered using a five-scale method, which was categorized into three to improve the efficiency of the analysis: Strongly and Somewhat likely, Neither Agree nor Disagree, and Strongly and Somewhat agree. Table 1 lists the items included in each component.

- Willingness to receive the vaccine. This part was assessed by addressing one question item: “In your current situation, how likely are you to make an appointment, then go and get vaccinated for COVID-19?” Willingness to receive the COVID-19 vaccine was responded to by a five-point scale, which was combined into three categories: Highly and Somewhat likely, Maybe, Somewhat, and Highly unlikely.

- Reasons (factors) to take the vaccine. The factors were subdivided into positive and negative factors. Respondents were asked to select the top three positive and negative factors that would influence their decision to undergo vaccination. Positive response options comprised 16 items, whereas negative response options comprised 17 items. Table 2 lists these items.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Risk Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2.1. Confidence in Knowledge

3.2.2. Concerns about COVID-19 Health Risk

3.2.3. Concerns about Economic Well-Being

3.3. Willingness to Receive Vaccinations

3.4. Reasons (Factors) to Receive Vaccination

3.4.1. Positive Factors

3.4.2. Negative Factors

3.5. Independent Predictors of Vaccination Willingness

3.5.1. Sociodemographic Attribute Index

- Income in Indonesia (AOR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.08–3.60, p < 0.05);

- (higher) Education in Thailand (AOR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.31–3.87; p < 0.05) and Indonesia (AOR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.30–4.67; p < 0.05);

- Work style, particularly retired or homemakers in Thailand (AOR, 5.19; 95% CI, 1.30–20.65; p < 0.05);

- Full-time or business owners in Vietnam (AOR, 4.43; 95% CI, 1.30–15.15; p < 0.05).

3.5.2. Perception of the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.5.3. Reasons for Vaccinations

Positive Factors

Negative Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations—Our World in Data 2022; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseilly, D.; Anwar, S.; Yufika, A.; Adam, R.; Ismaeil, M.; Dahman, N.; Hafs, M.; Ferjani, M.; Sami, F.; Monib, F.R.S.; et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination at different hypothetical efficacy and safety levels in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. Narra J. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; AI-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. A Global Map of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Rats per Country: And Updated Concise Narrative Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman, C.; Perera, A.; Condon, C.; Chau, C.; Quian, J.; Kalk, K.; Deleon, D. Factors Associated with Willingness to be Vaccinated Against COVID-19 in a Large Convenience Sample. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Technical Advisory Group. Acceptance and Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines Who Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and Sciences for Health; Meeting Report; WHO Technical Advisory Group: Geneva, Switzerland, 15 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J.; Khalid, O.; Islam, K.; Nur, N.; Ataullah, A.H.M.; Umbreem, H.; Itrat, N.; Ahmad, U.; Naeem, M.; Kabir, I.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in South Asia: A multi-country study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Kanwagi, R.; Tolossa, A.; Kalam, A.; Davis, T.; Larson, H.L. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Six Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. Res. Sq. Preprint 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Rocha, J.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Pedro, A. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzo, R.R.; Sami, W.; Alam, M.Z.; Acharaya, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Songwathana, K.; Pham, N.; Easpati, T.; Faller, E.; Baldonado, A.; et al. Hesitancy in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated factors among the general adult population: A cross-sectional study in six Southeast Asian countries. Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shurman, B.A.; Khan, A.F.; Mac, C.; Majeed, M.; Butt, Z.A. What Demographic, Social, and Contextual Factors Influence the Intention to Use COVID-19 Vaccines: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Wong, R. Vaccine hesitancy and preeived behavioral control: A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5131–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehal, K.R.; Steendam, L.M.; Campos Ponce, M.; van der Hoeven, M.; Smit, G.S.A. Worldwide Vaccination Willingness for COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, P.; Burrow, A.; Strecher, V. Sense of purpose in life predicts greater willingness for COVID-19 vaccination. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidry, J.; Laestadius, L.; Vraga, E.; Miller, C.; Perrin, P.; Burton, C.; Ryan, M.; Fuemmeler, B.; Carlyle, K. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JICA. Building Resilience COVID-19 Impact and Repsonses in Urban Areas; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hawlader, M.; Rahman, M.; Nazir, A.; Ara, T.; Haque, M.; Saha, S.; Barsha, S.; Hossian, M.; Matin, K.; Siddiquea, A.; et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.; Cheong, C.; Kong, G.; Phua, K.; Ngiam, J.; Tan, B.; Wang, B.; Hao, F.; Tan, W.; Han, X.; et al. An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers’ perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanto, T.; Octaviue, G.; Heriyanto, R.; Lienawi, C.; Nisa, H.; Pasal, H. Psychological factors afecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Indonesia. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2021, 57, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, M.C.; Nguye, H.T.; Duong, M. Evaluating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A qualitative study from Vietnam. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, T.; Suksatit, B.; Tokuda, M.; Katsuyama, H. Analysis of People’s Attitude Toward COVID-19 Vaccine and Its Information Sources in Thailand. Cureus 2022, 14, e22215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Question Items | |

|---|---|

| Confidence in Knowledge | |

| I am well read and know a lot about the coronavirus | |

| Concerns about health risk | |

| The world is in serious danger due to the coronavirus | |

| The coronavirus is similar to the regular flu and has similar death rates | |

| People of all ages are dying from the coronavirus | |

| I am safe from the virus where I live, but not the rest of world | |

| Most concerned about older relatives/parents | |

| Concerns about economic well-being. | |

| Current pandemic economic is worse than that of Global Financial Crisis of 2008 | |

| I am not financially secure because of the pandemic | |

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| Enabling environment | Enabling environment |

| It’s free | I do not know when and where to get it |

| Vaccine site is convenient/nearby | I do not have the ability to get an appointment |

| It’s easy to make an appointment | I cannot access an appointment time outside of my working hours |

| My employer provides paid time off to take it | I do not trust the sites where vaccines are being administered |

| Vaccine effect and safety | Vaccine effect and safety |

| Vaccines are safe and effective | Possible side-effects |

| Enough time has passed since people started taking it | Not enough evidence that it prevents COVID 19 |

| Experts say it is safe and effective | Approvals and clinical trials were too fast |

| Recommended by a physician/doctor | Not enough time since people started taking it |

| My loved ones recommended that I take it | Not enough people have taken the vaccine |

| People I know took it | Vaccines are not safe or effective in general |

| Leaders I trust took it | Storage of the vaccine is concerning |

| Risk Aversion | It contained human stem cells in its development |

| I’m afraid of getting COVID 19 | Clinical trials did not include adequate diversity or enough |

| Vaccines will keep my loved ones safe from COVID 19 | I am concerned it will impact my fertility or pregnancy |

| Lifestyle | Risk Aversion |

| To return to my previous lifestyle | I’m not afraid of getting COVID 19 |

| To return to work/school | I already had COVID 19 |

| Social Norm | Religious concerns |

| My employer requires me to take it |

| Thailand (n = 461) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 246) n (%) | Philippines (n = 609) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 526) n (%) | x2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| <35 | 193 (41.9) | 152 (61.8) | 413 (67.8) | 372 (70.7) | 104.05 | <0.001 | |

| ≥35 | 268 (58.1) | 94 (38.2) | 196 (32.2) | 154 (29.3) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 227 (49.2) | 130 (52.8) | 313 (51.4) | 272 (51.7) | 1.04 | 0.79 | |

| Female | 234 (50.8) | 116 (47.2) | 296 (48.6) | 254 (48.3) | |||

| Education | |||||||

| Up to secondary | 73 (15.8) | 77 (31.3) | 50 (8.2) | 42 (8.0) | 118.76 | <0.001 | |

| Tertiary and above | 386 (83.7) | 169 (68.7) | 538 (88.3) | 478 (90.9) | |||

| Others | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (3.5) | 6 (1.1) | |||

| Family type | |||||||

| Living alone | 68 (14.7) | 21 (8.5) | 50 (8.2) | 60 (11.4) | 32.72 | <0.001 | |

| Living with friends/partner/spouse with or without children | 224 (48.6) | 158 (64.3) | 314 (51.6) | 303 (57.6) | |||

| Multi-generation | 169 (36.7) | 67 (27.2) | 245 (40.2) | 163 (31.0) | |||

| Employment | |||||||

| Un-employed | 25 (5.4) | 17 (6.9) | 53 (8.7) | 14 (2.7) | 81.43 | <0.001 | |

| Retired or homemaker | 25 (5.4) | 10 (4.1) | 24 (3.9) | 5 (0.9) | |||

| Part-time | 79 (17.2) | 92 (37.4) | 117 (19.2) | 113 (21.5) | |||

| Full-time or business | 332 (72.0) | 127 (51.6) | 415 (68.2) | 394 (74.9) | |||

| Monthly household income | |||||||

| Below average | 127 (27.6) | 122 (49.6) | 435 (71.4) | 98 (18.6) | 480.96 | <0.001 | |

| Average | 158 (34.3) | 50 (20.3) | 83 (13.6) | 82 (15.6) | |||

| Above average | 176 (38.2) | 74 (30.1) | 91 (14.9) | 346 (65.8) | |||

| Income decreased due to COVID-19 | |||||||

| Yes | 307 (66.6) | 154 (62.6) | 338 (55.5) | 342 (65.0) | 17.11 | 0.001 | |

| No | 154 (33.4) | 92 (37.4) | 271 (44.5) | 184 (35.0) | |||

| Thailand (n = 461) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 246) n (%) | Philippines (n = 609) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 526) n (%) | x2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about COVID-19 | |||||||

| I am well read and know a lot about the coronavirus | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 29 (6.3) | 18 (7.3) | 85 (14.0) | 24 (4.6) | 95.68 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29 (6.3) | 54 (22.0) | 47 (7.7) | 37 (7.0) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 403 (87.4) | 174 (70.7) | 477 (78.3) | 465 (88.4) | |||

| Concerns about COVID-19 | |||||||

| The coronavirus is similar to the regular flu and has similar death rates | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 270 (58.6) | 108 (43.9) | 290 (47.6) | 364 (69.2) | 76.69 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 48 (10.4) | 41 (16.7) | 76 (12.5) | 56 (10.7) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 143 (31.0) | 97 (39.4) | 243 (39.9) | 106 (20.1) | |||

| People of all ages are dying from the coronavirus | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 121 (26.2) | 39 (15.9) | 91 (14.9) | 37 (7.0) | 129.92 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 72 (15.6) | 53 (21.5) | 44 (7.3) | 44 (8.4) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 268 (58.1) | 154 (62.6) | 474 (77.8) | 445 (84.6) | |||

| The world is in serious danger due to the coronavirus | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 27 (5.8) | 20 (8.1) | 32 (5.2) | 13 (2.5) | 49.78 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 28 (6.1) | 36 (14.7) | 34 (5.6) | 20 (3.8) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 406 (88.1) | 190 (77.2) | 543 (89.2) | 493 (93.7) | |||

| I am safe from the virus where I live, but not the rest of world | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 91 (19.7) | 108 (43.9) | 220 (36.1) | 274 (52.1) | 231.91 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 (8.3) | 66 (26.8) | 134 (22.0) | 98 (18.6) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 332 (72.0) | 72 (29.3) | 255 (41.9) | 154 (29.3) | |||

| Most concerned about older relatives/parents | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 24 (5.2) | 17 (6.9) | 52 (8.6) | 28 (5.3) | 71.15 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 27 (5.9) | 42 (17.1) | 13 (2.1) | 52 (9.9) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 410 (88.9) | 187 (76.0) | 544 (89.3) | 446 (84.8) | |||

| Concerns about economic well-being | |||||||

| Current pandemic economic is worse than that of Global Financial Crisis of 2008 | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 26 (5.6) | 49 (19.9) | 43 (7.1) | 49 (9.3) | 83.09 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 58 (12.6) | 59 (24.0) | 107 (17.6) | 132 (25.1) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 377 (81.8) | 138 (56.1) | 459 (75.31) | 345 (65.6) | |||

| I am not financially secure because of the pandemic | |||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 30 (6.5) | 35 (14.2) | 95 (15.6) | 84 (16.0) | 113.82 | <0.001 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 46 (10.0 | 58 (23.6) | 96 (15.8) | 159 (30.2) | |||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 385 (83.5) | 153 (62.2) | 418 (68.6) | 283 (53.8) | |||

| Thailand (n = 1010) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 1018) n (%) | Philippines (n = 1012) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 1032) n (%) | Total (n = 4072) n (%) | x2 | p | ||

| Eligible for the COVID19 vaccine | ||||||||

| Yes | 605 (59.9) | 668 (65.6) | 690 (68.2) | 721 (69.9) | 2684 (65.9) | 69.48 | <0.001 | |

| No | 158 (15.6) | 183 (18.0) | 92 (9.1) | 104 (10.1) | 537 (13.2) | |||

| Don’t know | 247 (24.5) | 167 (16.4) | 230 (22.7) | 207 (20.0) | 851 (20.9) | |||

| Thailand (n = 605) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 668) n (%) | Philippines (n = 690) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 721) n (%) | Total (n = 2684) n (%) | x2 | p | ||

| Already vaccinated | ||||||||

| Yes | 144 (23.8) | 422 (63.2) | 81 (11.7) | 195 (27.1) | 842 (31.4) | 459.69 | <0.001 | |

| No | 461 (76.2) | 246 (36.8) | 609 (88.3) | 526 (72.9) | 1842 (68.6) | |||

| Thailand (n = 461) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 246) n (%) | Philippines (n = 609) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 526) n (%) | Total (n = 1842) n (%) | x2 | p | ||

| Willing to get vaccinated (out of unvaccinated) | ||||||||

| Highly & somewhat unlikely | 50 (10.9) | 11 (4.5) | 44 (7.2) | 48 (9.2) | 153 (8.3) | 28.02 | <0.001 | |

| May be | 120 (26.0) | 66 (26.8) | 104 (17.1) | 117 (22.2) | 407 (22.1) | |||

| Highly & somewhat likely | 291 (63.1) | 169 (68.7) | 461 (75.7) | 361 (68.6) | 1282 (69.6) | |||

| Positive | Thailand (n = 461) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 246) n (%) | Philippines (n = 609) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 526) n (%) | x2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enabling environment | |||||||

| It’s free | |||||||

| Not selected | 284 (61.6) | 175 (71.1) | 437 (71.8) | 433 (82.3) | 52.75 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 177 (38.4) | 71 (28.9) | 172 (28.2) | 93 (17.7) | |||

| Vaccine site is convenient/nearby | |||||||

| Not selected | 404 (87.6) | 208 (84.5) | 582 (95.6) | 473 (89.9) | 32.90 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 57 (12.4) | 38 (15.5) | 27 (4.4) | 53 (10.1) | |||

| It is easy to make an appointment | |||||||

| Not selected | 425 (92.2) | 222 (90.2) | 599 (98.4) | 503 (95.6) | 33.94 | <0.0001 | |

| Selected | 36 (7.8) | 24 (9.8) | 10 (1.6) | 23 (4.4) | |||

| My employer provides paid time off to take it | |||||||

| Not selected | 444 (96.3) | 232 (94.3) | 573 (94.1) | 503 (95.6) | 3.44 | 0.33 | |

| Selected | 17 (3.7) | 14 (5.7) | 36 (5.9) | 23 (4.4) | |||

| Vaccine effect and safety | |||||||

| Vaccines are safe and effective | |||||||

| Not selected | 303 (65.7) | 170 (69.1) | 418 (68.6) | 251 (47.7) | 64.91 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 158 (34.3) | 76 (30.9) | 191 (31.4) | 275 (52.3) | |||

| Enough time has passed since people started taking it | |||||||

| Not selected | 417 (90.5) | 221 (89.8) | 576 (94.6) | 499 (94.9) | 13.51 | 0.004 | |

| Selected | 44 (9.5) | 25 (10.2) | 33 (5.4) | 27 (5.1) | |||

| Experts say it is safe and effective | |||||||

| Not selected | 354 (76.8) | 167 (67.9) | 376 (61.7) | 382 (72.6) | 21.54 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 107 (23.2) | 79 (32.1) | 233 (38.3) | 144 (27.4) | |||

| Recommended by a physician/doctor | |||||||

| Not selected | 378 (82.0) | 196 (79.7) | 508 (83.4) | 464 (88.2) | 11.86 | <0.00 | |

| Selected | 83 (18.0) | 50 (30.3) | 101 (16.6) | 62 (11.8) | |||

| My loved ones recommended that I take it | |||||||

| Not selected | 433 (93.9) | 213 (86.6) | 569 (93.4) | 483 (91.8) | 14.05 | 0.003 | |

| Selected | 28 (6.1) | 33 (13.4) | 40 (6.6) | 43 (8.2) | |||

| People I know took it | |||||||

| Not selected | 436 (94.6) | 218 (88.6) | 577 (94.8) | 487 (92.6) | 12.24 | 0.01 | |

| Selected | 25 (5.4) | 28 (11.4) | 32 (5.2) | 39 (7.4) | |||

| Leaders I trust took it | |||||||

| Not selected | 432 (93.7) | 219 (89.0) | 588 (96.5) | 476 (90.5) | 23.50 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 29 (6.3) | 27 (11.0) | 21 (3.5) | 50 (9.5) | |||

| Risk Aversion | |||||||

| I’m afraid of getting COVID 19 | |||||||

| Not selected | 280 (60.7) | 178 (72.4) | 353 (58.0) | 252 (47.9) | 44.08 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 181 (39.3) | 68 (27.6) | 256 (42.0) | 274 (52.1) | |||

| Vaccines will keep my loved ones safe from COVID 19 | |||||||

| Not selected | 259 (56.2) | 146 (59.4) | 271 (44.5) | 294 (55.9) | 25.19 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 202 (43.8) | 100 (40.6) | 338 (55.5) | 232 (44.1) | |||

| Lifestyle | |||||||

| To return to my previous lifestyle | |||||||

| Not selected | 326 (70.7) | 212 (86.2) | 476 (78.2) | 427 (81.2) | 27.10 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 135 (29.3) | 34 (13.8) | 133 (21.8) | 99 (18.8) | |||

| To return to work/school | |||||||

| Not selected | 415 (90.0) | 207 (84.2) | 513 (84.2) | 451 (85.7) | 8.53 | 0.04 | |

| Selected | 46 (10.0) | 39 (15.8) | 96 (15.8) | 75 (14.3) | |||

| Social Norm | |||||||

| My employer requires me to take it | |||||||

| Not selected | 428 (92.8) | 232 (94.3) | 533 (87.5) | 488 (92.8) | 16.50 | 0.001 | |

| Selected | 33 (7.2) | 14 (5.7) | 76 (12.5) | 38 (7.2) | |||

| Others | |||||||

| Not selected | 457 (99.1) | 245 (99.6) | 605 (99.3) | 536 (100.0) | 4.33 | 0.23 | |

| Selected | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Negative | Thailand (n = 461) n (%) | Indonesia (n = 246) n (%) | Philippines (n = 609) n (%) | Vietnam (n = 526) n (%) | x2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enabling environment | |||||||

| I do not know when and where to get it | |||||||

| Not selected | 409 (88.7) | 179 (72.8) | 523 (85.9) | 372 (70.7) | 72.51 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 52 (11.3) | 67 (27.2) | 86 (14.1) | 154 (29.3) | |||

| I do not have the ability to get an appointment | |||||||

| Not selected | 417 (90.5) | 201 (81.7) | 541 (88.8) | 442 (84.0) | 16.77 | 0.001 | |

| Selected | 44 (9.5) | 45 (18.3) | 68 (11.2) | 84 (16.0) | |||

| I cannot access an appointment time outside of my working hours | |||||||

| Not selected | 431 (93.5) | 208 (84.5) | 561 (92.1) | 477 (90.7) | 17.04 | 0.001 | |

| Selected | 30 (6.5) | 38 (15.5) | 48 (7.9) | 49 (9.3) | |||

| I do not trust the sites where vaccines are being administered | |||||||

| Not selected | 418 (90.7) | 217 (88.2) | 502 (82.4) | 460 (87.5) | 16.68 | 0.001 | |

| Selected | 43 (9.3) | 29 (11.8) | 107 (17.6) | 66 (12.5) | |||

| Vaccine effect and safety | |||||||

| Possible side-effects | |||||||

| Not selected | 111 (24.1) | 115 (46.7) | 164 (26.9) | 234 (44.5) | 77.51 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 350 (75.9) | 131 (53.3) | 445 (73.1) | 292 (55.5) | |||

| Not enough people have taken the vaccine | |||||||

| Not selected | 424 (92.0) | 206 (83.7) | 494 (81.1) | 449 (85.4) | 25.48 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 37 (8.0) | 40 (16.3) | 115 (18.9) | 77 (14.6) | |||

| Approvals and clinical trials were too fast | |||||||

| Not selected | 398 (86.3) | 206 (83.7) | 439 (72.1) | 465 (88.4) | 61.17 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 63 (13.7) | 40 (16.3) | 170 (27.9) | 61 (11.6) | |||

| Not enough evidence that it prevents COVID 19 | |||||||

| Not selected | 300 (65.1) | 187 (76.0) | 384 (63.1) | 398 (75.7) | 29.90 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 161 (34.9) | 59 (24.0) | 225 (36.9) | 128 (24.3) | |||

| Not enough time since people started taking it | |||||||

| Not selected | 425 (92.2) | 214 (87.0) | 539 (88.5) | 432 (82.1) | 23.60 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 36 (7.8) | 32 (13.0) | 70 (11.5) | 94 (17.9) | |||

| Vaccines are not safe or effective in general | |||||||

| Not selected | 174 (37.7) | 214 (87.0) | 499 (81.9) | 460 (87.5) | 396.75 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 287 (62.3) | 32 (13.0) | 110 (18.1) | 66 (12.5) | |||

| Storage of the vaccine is concerning | |||||||

| Not selected | 416 (90.2) | 210 (85.4) | 543 (89.2) | 414 (78.7) | 35.12 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 45 (9.8) | 36 (14.6) | 66 (10.8) | 112 (21.3) | |||

| It contained human stem cells in its development | |||||||

| Not selected | 429 (93.1) | 224 (91.1) | 584 (95.9) | 475 (90.3) | 15.02 | 0.002 | |

| Selected | 32 (6.9) | 22 (8.9) | 25 (4.1) | 51 (9.7) | |||

| Clinical trials did not include adequate diversity or enough people of color | |||||||

| Not selected | 400 (86.8) | 208 (84.5) | 491 (80.6) | 445 (84.6) | 7.88 | 0.05 | |

| Selected | 61 (13.2) | 38 (15.5) | 118 (19.4) | 81 (15.4) | |||

| I am concerned it will impact my fertility or pregnancy | |||||||

| Not selected | 418 (90.7) | 212 (86.2) | 565 (92.8) | 423 (80.4) | 45.11 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 43 (9.3) | 34 (13.8) | 44 (7.2) | 103 (19.6) | |||

| Others | |||||||

| Not selected | 448 (97.2) | 242 (98.4) | 594 (97.5) | 516 (98.1) | 1.51 | 0.68 | |

| Selected | 13 (2.8) | 4 (1.6) | 15 (2.5) | 10 (1.9) | |||

| Risk Aversion | |||||||

| I’m not afraid of getting COVID 19 | |||||||

| Not selected | 440 (95.4) | 225 (91.1) | 560 (91.9) | 498 (94.7) | 8.86 | 0.03 | |

| Selected | 21 (4.6) | 22 (8.9) | 49 (8.1) | 28 (5.3) | |||

| I already had COVID 19 | |||||||

| Not selected | 452 (98.1) | 229 (93.1) | 603 (99.0) | 512 (97.3) | 26.02 | <0.001 | |

| Selected | 9 (1.9) | 17 (6.9) | 6 (1.0) | 14 (2.7) | |||

| Religious concerns | |||||||

| Not selected | 455 (98.7) | 229 (93.1) | 588 (96.5) | 501 (92.3) | 16.10 | 0.001 | |

| Selected | 6 (1.3) | 17 (6.9) | 21 (3.5) | 25 (4.7) | |||

| Thailand | Indonesia | Philippines | Vietnam | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| >34 | 1.20 (0.79–1.83) | 0.38 | 2.35 (1.20–4.59) | <0.05 | 1.27 (0.82–1.98) | 0.28 | 0.50 (0.31–0.78) | <0.05 | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Female | 0.70 (0.47–1.05) | 0.09 | 0.87 (0.48–1.60) | 0.66 | 0.96 (0.65–1.42) | 0.86 | 1.34 (0.90–2.02) | 0.15 | |

| Monthly household income | |||||||||

| Below average | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Average | 1.43 (0.85–2.39) | 0.18 | 1.73 (0.74–4.07) | 0.21 | 0.96 (0.54–1.70) | 0.89 | 0.81 (0.42–1.54) | 0.52 | |

| Above average | 0.89 (0.52–1.52) | 0.67 | 1.05 (0.5–2.14) | 0.90 | 1.20 (0.67–2.13) | 0.55 | 1.87 (1.10–3.20) | <0.05 | |

| Income decreased due to COVID-19 | |||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 0.90 (0.59–1.38) | 0.63 | 1.97 (1.08–3.60) | <0.05 | 0.88 (0.59–1.31) | 0.52 | 1.47 (1.00–2.25) | 0.07 | |

| Education | |||||||||

| Up to secondary | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Tertiary and above | 2.25 (1.31–3.87) | <0.05 | 2.46 (1.3–4.67) | <0.05 | 1.60 (0.84–3.05) | 0.15 | 1.63 (0.81–3.27) | 0.17 | |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Un-employed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Retired or homemaker | 5.19 (1.30–0.65) | <0.05 | 1.47 (0.18–11.84) | 0.72 | 0.60 (0.21–1.73) | 0.35 | 2.16 (0.24–19.50) | 0.49 | |

| Part-time | 0.89 (0.35–2.26) | 0.79 | 0.80 (0.22–2.97) | 0.74 | 1.20 (0.57–2.50) | 0.64 | 2.01 (0.58–7.02) | 0.27 | |

| Full-time or business | 1.68 (0.71–4.01) | 0.24 | 0.99 (0.27–3.63) | 0.99 | 1.25 (0.64–2.44) | 0.51 | 4.43 (1.30–15.15) | <0.05 | |

| Family type | |||||||||

| Living alone | 1 | ||||||||

| Living with friends/partner/spouse with or without children | 1.19 (0.66–2.18) | 0.56 | 0.80 (0.28–2.32) | 0.68 | 1.08 (0.54–2.19) | 0.82 | 0.86 (0.43–1.71) | 0.67 | |

| Multi-generation | 1.10 (0.60–2.03) | 0.76 | 1.03 (0.33–3.18) | 0.96 | 1.10 (0.54–2.23) | 0.80 | 0.39 (0.20–0.78) | <0.05 | |

| Thailand | Indonesia | Philippines | Vietnam | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Confidence in Knowledge | |||||||||

| I am well read and know a lot about the coronavirus | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.41 (0.44–4.43) | 0.56 | 0.85 (0.21–3.48) | 0.82 | 0.47 (0.20–1.12) | 0.09 | 0.30 (0.09–0.99) | 0.05 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 2.07 (0.92–4.65) | 0.08 | 1.04 (0.28–3.87) | 0.96 | 0.73 (0.39–1.37) | 0.33 | 0.82 (0.31–2.19) | 0.69 | |

| Concerns about CVID-19 health risk | |||||||||

| The coronavirus is similar to the regular flu and has similar death rates | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.07 (0.52–2.19) | 0.86 | 0.74 (0.28–1.98) | 0.55 | 0.45 (0.24–0.82) | <0.05 | 0.72 (0.34–1.51) | 0.39 | |

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1.41 (0.86–2.28) | 0.17 | 0.79 (0.38–1.65) | 0.53 | 0.96 (0.61–1.52) | 0.88 | 1.13 (0.69–1.85) | 0.62 | |

| People of all ages are dying from the coronavirus | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.35 (0.69–2.65) | 0.38 | 1.22 (0.42–3.57) | 0.71 | 2.32 (0.95–5.68) | 0.07 | 0.62 (0.23–1.66) | 0.34 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 1.16 (0.71–1.90) | 0.56 | 1.51 (0.59–3.89) | 0.39 | 1.77 (1.00–3.13) | <0.05 | 1.65 (0.77–3.55) | 0.20 | |

| The world is in serious danger due to the coronavirus | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.51 (0.15–1.74) | 0.28 | 3.26 (0.78–13.58) | 0.11 | 1.19 (0.40–3.57) | 0.75 | 0.63 (0.12–3.39) | 0.59 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 0.66 (0.27–1.64) | 0.37 | 8.28 (2.23–30.74) | <0.05 | 3.22 (1.38–7.52) | <0.05 | 0.89 (0.23–3.45) | 0.87 | |

| I am safe from the virus where I live, but not the rest of world | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.53 (0.22–1.30) | 0.17 | 0.63 (0.28–1.40) | 0.26 | 0.52 (0.31–0.88) | <0.05 | 1.61 (0.91–2.87) | 0.10 | |

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 0.59 (0.34–1.04) | 0.07 | 1.18 (0.53–2.64) | 0.69 | 0.88 (0.55–1.42) | 0.61 | 1.00 (0.64–1.57) | 0.99 | |

| Most concerned about older relatives/parents | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2.12 (0.55–8.23) | 0.28 | 3.98 (0.91–17.28) | 0.07 | 1.49 (0.31–7.08) | 0.62 | 0.73 (0.25–2.16) | 0.58 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 0.95 (0.37–2.41) | 0.91 | 4.47 (1.28–15.59) | <0.05 | 0.98 (0.47–2.01) | 0.95 | 0.89 (0.35–2.24) | 0.80 | |

| Financial Concern | |||||||||

| Current pandemic economic is worse than that of Global Financial Crisis of 2008 | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.12 (0.38–3.30) | 0.83 | 1.05 (0.41–2.70) | 0.91 | 1.35 (0.57–3.19) | 0.49 | 1.11 (0.53–2.29) | 0.79 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 0.71 (0.28–1.78) | 0.46 | 1.55 (0.67–3.60) | 0.31 | 1.57 (0.73–3.34) | 0.24 | 1.33 (0.68–2.61) | 0.40 | |

| I am not financially secure because of the pandemic | |||||||||

| Strongly & somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.08 (0.36–3.20) | 0.89 | 0.24 (0.07–0.78) | <0.05 | 1.59 (0.77–3.29) | 0.21 | 1.14 (0.63–2.07) | 0.66 | |

| Strongly & somewhat agree | 0.69 (0.29–1.66) | 0.41 | 0.38 (0.12–1.15) | 0.09 | 1.09 (0.63–1.89) | 0.76 | 1.28 (0.74–2.21) | 0.37 | |

| Willingness for vaccination (Unlikely = 0, Likely = 1) | Thailand | Indonesia | Philipines | Vietnam | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | AOR (95% CI ) | p | AOR (95% CI ) | p | AOR (95% CI ) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Enabling environment | |||||||||

| It’sfree | 0.57 (0.37–0.86) | <0.01 | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | <0.05 | 0.64 (0.43–0.97) | <0.05 | 0.98 (0.59–1.65) | 0.96 | |

| Vaccinesiteisconvenient/nearby | 0.72 (0.39–1.31) | 0.28 | 0.47 (0.21–1.06) | 0.07 | 0.50 (0.22–1.14) | 0.10 | 1.23 (0.62–2.41) | 0.55 | |

| Easytomakeanappointment | 0.95 (0.45–2.03) | 0.90 | 0.76 (0.29–1.99) | 0.58 | 0.31 (0.08–1.10) | 0.07 | 2.48 (0.76–8.05) | 0.13 | |

| Myemployerprovidespaidtimeofftotakeit | 1.43 (0.48–4.28) | 0.52 | 0.64 (0.19–2.19) | 0.48 | 0.70 (0.33–1.51) | 0.37 | 1.33 (0.48–3.71) | 0.58 | |

| Vaccine effect and safety | |||||||||

| Vaccines are safe and effective | 0.68 (0.44–1.03) | 0.07 | 0.86 (0.45–1.65) | 0.66 | 1.40 (0.92–2.14) | 0.12 | 1.14 (0.76–1.72) | 0.52 | |

| Enough time has passed since people started taking it | 0.34 (0.18–0.67) | <0.01 | 4.27 (1.16–15.67) | <0.05 | 0.49 (0.23–1.04) | 0.06 | 0.32 (0.14–0.75) | <0.01 | |

| Experts say it is safe and effective | 0.61 (0.38–0.98) | <0.05 | 1.31 (0.69–2.48) | 0.41 | 1.30 (0.88–1.92) | 0.19 | 0.88 (0.56–1.37) | 0.58 | |

| Recommended by a physician/doctor | 0.98 (0.58–1.64) | 0.94 | 1.19 (0.57–2.46) | 0.64 | 0.84 (0.51–1.38) | 0.49 | 0.71 (0.39–1.27) | 0.25 | |

| My loved ones recommended that I take it | 1.07 (0.46–2.46) | 0.88 | 0.74 (0.33–1.67) | 0.47 | 1.39 (0.62–3.13) | 0.43 | 1.40 (0.64–3.05) | 0.40 | |

| People I know took it | 1.83 (0.69–4.85) | 0.22 | 0.79 (0.31–2.05) | 0.64 | 0.51 (0.24–1.09) | 0.08 | 0.88 (0.41–1.88) | 0.74 | |

| Leaders I trust took it | 0.96 (0.42–2.15) | 0.91 | 0.57 (0.23–1.40) | 0.22 | 0.91 (0.34–2.45) | 0.85 | 1.10 (0.56–2.17) | 0.27 | |

| Risk Aversion | |||||||||

| I’m afraid of getting COVID 19 | 1.38 (0.91–2.09) | 0.13 | 1.43 (0.73–2.79) | 0.29 | 1.97 (1.31–2.95) | <0.01 | 1.03 (0.69–1.54) | 0.88 | |

| Vaccines will keep my loved ones safe from COVID 19 | 2.49 (1.64–3.80) | <0.001 | 5.09 (2.47–10.49) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.12–2.41) | <0.05 | 1.49 (0.98–2.25) | 0.06 | |

| Lifestyle | |||||||||

| To return to my previous lifestyle | 1.27 (0.81–1.98) | 0.29 | 0.77 (0.34–1.75) | 0.54 | 1.25 (0.78–2.02) | 0.35 | 0.76 (0.46–1.25) | 0.28 | |

| To return to work/school | 1.64 (0.80–3.34) | 0.17 | 0.77 (0.36–1.67) | 0.51 | 0.85 (0.51–1.40) | 0.52 | 1.09 (0.61–1.94) | 0.77 | |

| Social Norm | |||||||||

| My employer requires me to take it | 1.86 (0.79–4.35) | 0.16 | 0.67 (0.19–2.33) | 0.53 | 0.45 (0.27–0.75) | <0.01 | 0.83 (0.38–1.82) | 0.65 | |

| Willingness for vaccination (Unlikely = 0, Likely = 1) | Thailand | Indonesia | Philipines | Vietnam | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Enabling environment | |||||||||

| I do not know when and where to get it | 0.84 (0.45–1.57) | 0.58 | 1.35 (0.68–2.65) | 0.39 | 1.42 (0.80–2.52) | 0.23 | 1.05 (0.68–1.63) | 0.82 | |

| I do not have the ability to get an appointment | 3.85 (1.61–9.20) | <0.01 | 1.01 (0.48–2.14) | 0.97 | 3.36 (1.49–7.59) | <0.01 | 1.29 (0.72–2.29) | 0.39 | |

| I cannot access an appointment time outside of my working hours | 2.36 (0.92–6.04) | 0.07 | 1.25 (0.56–2.83) | 0.58 | 1.60 (0.72–3.55) | 0.24 | 1.38 (0.68–2.83) | 0.37 | |

| I do not trust the sites where vaccines are being administered | 1.08 (0.55–2.13) | 0.82 | 0.25 (0.10–0.62) | <0.01 | 1.03 (0.63–1.70) | 0.90 | 1.14 (0.63–2.07) | 0.67 | |

| Vaccine effect and safety | |||||||||

| Possible side-effects | 0.66 (0.40–1.07) | 0.09 | 0.90 (0.49–1.65) | 0.73 | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 0.50 | 0.53 (0.34–0.80) | <0.01 | |

| Not enough evidence that it prevents COVID 19 | 0.54 (0.36–0.83) | <0.01 | 1.17 (0.58–2.35) | 0.67 | 0.58 (0.39–0.85) | <0.01 | 0.70 (0.45–1.11) | 0.13 | |

| Approvals and clinical trials were too fast | 2.11 (1.11–4.03) | <0.05 | 2.29 (0.95–5.51) | 0.07 | 0.69 (0.46–1.04) | 0.08 | 1.07 (0.57–2.01) | 0.83 | |

| Not enough time since people started taking it | 0.80 (0.38–1.68) | 0.56 | 1.04 (0.44–2.45) | 0.93 | 0.95 (0.53–1.71) | 0.88 | 0.84 (0.51–1.40) | 0.51 | |

| Not enough people have taken the vaccine | 1.99 (0.90–4.41) | 0.09 | 0.62 (0.28–1.34) | 0.23 | 0.76 (0.48–1.20) | 0.24 | 0.84 (0.4–1.49) | 0.55 | |

| Vaccines are not safe or effective in general | 0.43 (0.28–0.66) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.33–1.80) | 0.54 | 0.57 (0.36–0.90) | <0.05 | 0.97 (0.53–1.79) | 0.93 | |

| Storage of the vaccine is concerning | 0.72 (0.37–1.40) | 0.33 | 1.59 (0.67–3.75) | 0.29 | 1.24 (0.66–2.33) | 0.50 | 1.67 (0.99–2.83) | 0.06 | |

| It contained human stem cells in its development | 2.14 (0.88–5.21) | 0.09 | 0.96 (0.33–2.79) | 0.95 | 1.30 (0.47–3.59) | 0.61 | 3.92 (1.60–9.60) | <0.01 | |

| Clinical trials did not include adequate diversity or enough | 1.18 (0.65–2.12) | 0.59 | 1.12 (0.49–2.54) | 0.78 | 1.39 (0.83–2.32) | 0.20 | 1.22 (0.70–2.13) | 0.48 | |

| I am concerned it will impact my fertility or pregnancy | 2.22 (1.03–4.76) | <0.05 | 1.59 (0.65–3.88) | 0.30 | 0.89 (0.44–1.79) | 0.74 | 1.32 (0.77–2.24) | 0.31 | |

| Risk Aversion | |||||||||

| I’m not afraid of getting COVID 19 | 0.88 (0.35–2.23) | 0.79 | 0.63 (0.23–1.71) | 0.37 | 2.22 (0.95–3.15) | 0.06 | 1.07 (0.42–2.72) | 0.88 | |

| Religious concerns | 1.04 (0.18–5.96) | 0.96 | 0.45 (0.15–1.39) | 0.17 | 1.46 (0.48–4.47) | 0.51 | 1.04 (0.40–2.68) | 0.94 | |

| I already had COVID-19 | 4.92 (0.58–41.64) | 0.14 | 1.47 (0.43–5.09) | 0.54 | 1.45 (0.16–13.08) | 0.74 | 0.55 (0.17–1.78) | 0.32 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saito, K.; Komasawa, M.; Aung, M.N.; Khin, E.T. COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness in Four Asian Countries: A Comparative Study including Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912284

Saito K, Komasawa M, Aung MN, Khin ET. COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness in Four Asian Countries: A Comparative Study including Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912284

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaito, Kiyoko, Makiko Komasawa, Myo Nyein Aung, and Ei Thinzar Khin. 2022. "COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness in Four Asian Countries: A Comparative Study including Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912284

APA StyleSaito, K., Komasawa, M., Aung, M. N., & Khin, E. T. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness in Four Asian Countries: A Comparative Study including Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912284