Students’ Perceived Well-Being and Online Preference: Evidence from Two Universities in Vietnam during COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Has the COVID-19 epidemic had a negative influence on students’ health, notably in terms of reported stress, perceived health impact, and perceived future worries?

- How would students prefer online classes in the future, and what factors are associated with this preference?

- What kind of support is needed for students to reduce the impact?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

3.2. Students’ Perceived Impacts on Academic Life and Well-Being

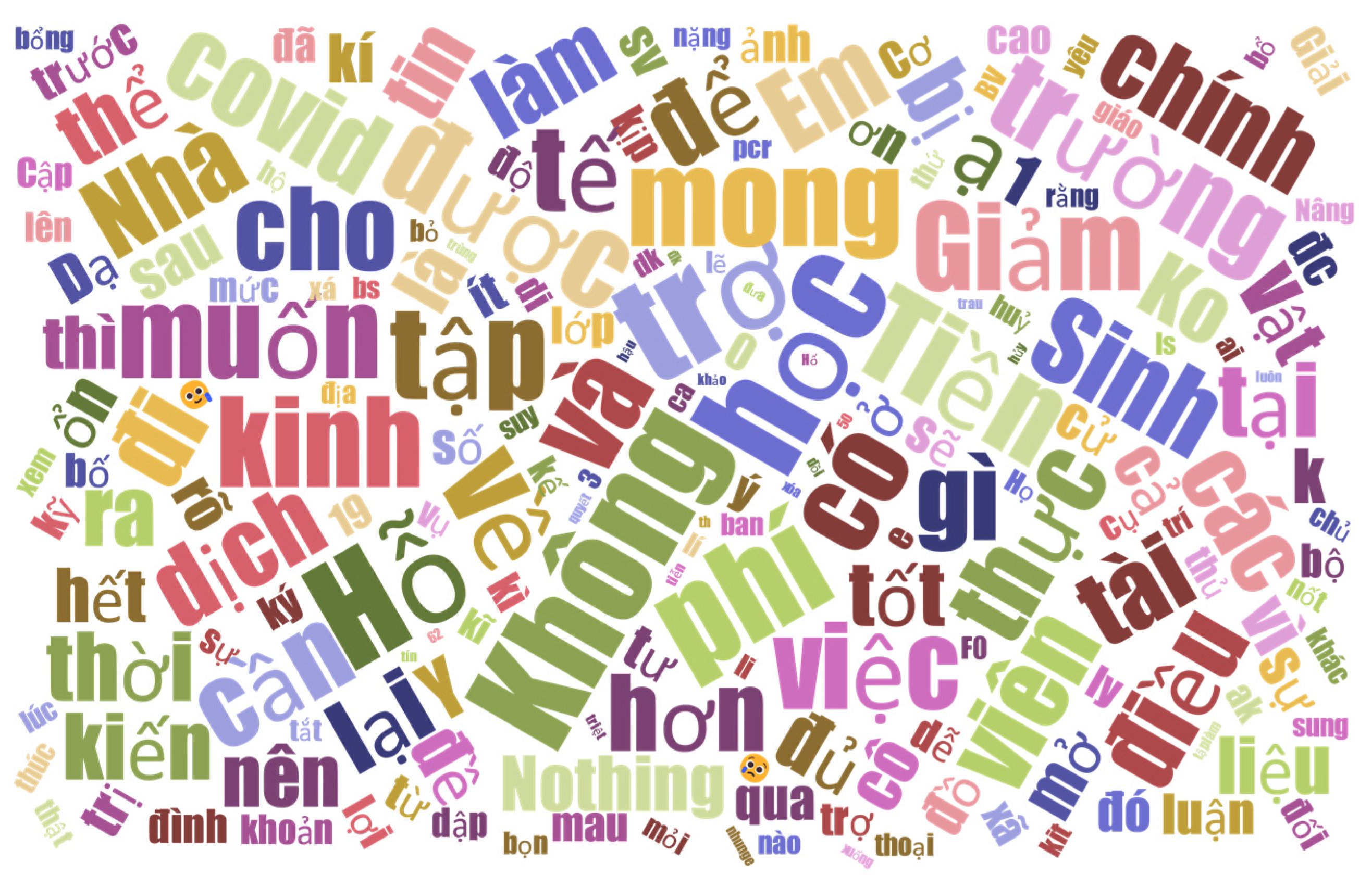

3.3. Results of Qualitative Data on COVID-19 Impacts on Students’ Campus Life

3.4. Conceptual Framework of COVID-19 Impacts on Students’ Campus Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ridner, S.L.; Newton, K.S.; Staten, R.R.; Crawford, T.N.; Hall, L.A. Predictors of Well-Being among College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2016, 64, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, B.; Koutsopouloub, G.; Miles, J.; Slaad, E.; Barkham, M. Changes in Undergraduate Students’ Psychological Well-Being as They Progress through University. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiter, R.; Nash, R.; McCrady, M.; Rhoades, D.; Linscomb, M.; Clarahan, M.; Sammut, S. The Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a Sample of College Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 173, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, S.; Gyda Gudmundsdot, T.I.B.; Marraccini, M.; Munro, B.; Zavras, B.; Weyandt, L.; Hysenbegasi, A.; Hass, S.L.; Rowland, C.R. The Impact of Depression on the Academic Productivity of University Students. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2005, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ratanasiripong, P.; China, T.; Toyama, S. Mental Health and Well-Being of University Students in Okinawa. Educ. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, V. Supporting the Well-Being of Medical Students. CMAJ 2005, 172, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, D.; Keough, G.; Perez-Dominguez, F.; Polanco-Ilabaca, F.; Pinto-Toledo, F.; Michaeli, J.; Albers, S.; Achiardi, J.; Santana, V.; Urnelli, C.; et al. Medical Education and Mental Health during COVID-19: A Survey across 9 Countries. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2022, 13, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.M.; Lumbreras, J. Higher Education and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Navigating Disruption Using the Sustainable Development Goals. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Kim, D.J. Higher Education Amidst COVID-19: Challenges and Silver Lining. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 37, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The Transformation of Higher Education After the COVID Disruption: Emerging Challenges in an Online Learning Scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, T.; Leppänen, U.; Hyypiä, M.; Kokko, A.; Manninen, J.; Vartiainen, H.; Sointu, E.; Hirsto, L. Learning Environments Preferred by University Students: A Shift toward Informal and Flexible Learning Environments. Learn. Environ. Res. 2021, 24, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Bista, K.; Allen, R.M. Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19: International Perspectives and Experiences, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nursjanti, F.; Amaliawiati, L.; Nurani, N. Impact of Covid-19 on Higher Education Institutions in Indonesia. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2021, 11, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Paek, S.; Park, S.; Park, J. A News Big Data Analysis of Issues in Higher Education in Korea amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Black, K.; Blenkinsopp, J.; Charlton, H.; Hookham, C.; Pok, W.F.; Sia, B.C.; Alkarabsheh, O.H.M. Higher Education under Threat: China, Malaysia, and the UK Respond to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2021, 52, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Yan-Li, S.; Kanit, P.; Joko, S. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Comparison Among Higher Education Students in Four Countries in the Asia-Pacific Region. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2021, 29, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongkhon, P.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Nochaiwong, S. Exposure to COVID-19-Related Information and Its Association with Mental Health Problems in Thailand: Nationwide, Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.A.T.; Vodden, K.; Wu, J.; Atiwesh, G. Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.T.; Quoc, H.H. Student Barriers To Prospects of Online Learning in Vietnam in the Context of Covid-19 Pandemic. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 2021, 22, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.L.; Giang, T.V.; Ho, D.K. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Online Learning in Higher Education: A Vietnamese Case. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.K.; Dinh, H.; Nguyen, H.; Le, D.-N.; Nguyen, D.-K.; Tran, A.C.; Nguyen-Hoang, V.; Nguyen, H.; Thu, T.; Hung, D.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: An Online Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VNU-HCM. Impacts of COVID-19 on Mental Health of VNU-HCM students. Available online: https://vnuhcm.edu.vn/su-kien-sap-dien-ra/su-tac-dong-cua-covid-19-den-suc-khoe-tam-than-cua-sinh-vien-dhqg-hcm/343034336864.html?fbclid=IwAR3s02HInyWCxKL5T4S60r21JnQ2iNfPz1hRANcXHrHdCOWrcAgiQgEde_4 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Trường Đại học Y Dược Thái Bình. Available online: http://tbump.edu.vn/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Vietnam National University of Agriculture. Available online: https://eng.vnua.edu.vn/ (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Tran, H.N. International Students’ Acceptance of Online Learning During Pandemic: Some Exploratory Findings. In Proceedings of the IAFOR International Conference on Education in Hawaii 2022 Official Conference Proceedings, Honolulu, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2022; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Marinova, K. Students’ Experience Two Years Into the Pandemic at a Bulgarian University. In Proceedings of the Paris Conference on Education, Paris, France, 16–19 June 2022; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Kanchana, P.; Do, K.L.; Khan, Y.A. Health Impact Perceived by University Students at Three Sites in Asia: Two Years Into the Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Asian Studies 2022: Official Conference Proceedings, Tokyo, Japan, 19–22 May 2022; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word Cloud Generator. Available online: https://www.jasondavies.com/wordcloud/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Tran, H.N.; Inosaki, A.; Jin, C.-H. Online Seminar: A Potential Mental Health Support Tool for International Students. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on New Approaches in Education, London, UK, 4–6 February 2022; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Inosaki, A.; Tran, H.; Jin, C.-H. Stress Coping Seminar for International Students: Initiatives at Tokushima University. Bull. Int. Off. Tokushima Univ. 2022, 1, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Lucock, M. The Mental Health of University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Online Survey in the UK. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochnik, D.; Rogowska, A.M.; Kuśnierz, C.; Jakubiak, M.; Schütz, A.; Held, M.J.; Arzenšek, A.; Benatov, J.; Berger, R.; Korchagina, E.V.; et al. A Comparison of Depression and Anxiety among University Students in Nine Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Franzen, J.; Jermann, F.; Rudaz, S.; Bondolfi, G.; Ghisletta, P. Psychological Distress and Well-Being among Students of Health Disciplines in Geneva, Switzerland: The Importance of Academic Satisfaction in the Context of Academic Year-End and COVID-19 Stress on Their Learning Experience. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, J.A.; King, N.; Saunders, K.E.; Bast, A.; Rivera, D.; Byun, J.; Cunningham, S.; Khera, C.; Duffy, A.C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Experience and Mental Health of University Students Studying in Canada and the UK: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, M.; Sahu, B. A Comparative Study on Mental Health of Rural and Urban Students. Int. Educ. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 7, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Ahmmed, F.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Sanam, S.; Emran, T.B.; Mitra, S. Impact of Online Education on Fear of Academic Delay and Psychological Distress among University Students Following One Year of COVID-19 Outbreak in Bangladesh. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.Y.K.; Lee, L.; Wang, M.P.; Feng, Y.; Lai, T.T.K.; Ho, L.M.; Lam, V.S.F.; Ip, M.S.M.; Lam, T.H. Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on International University Students, Related Stressors, and Coping Strategies. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Solomon, M.; Stead, T.; Kwon, B.; Ganti, L. Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of US College Students. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabaugh, A.; Duque, J.F.; Fields, L.J. Academic Stress and Emotional Well-Being in United States College Students Following Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Riad, A. Gender Differences in Depressive Traits among Rural and Urban Chinese Adolescent Students: Secondary Data Analysis of Nationwide Survey CFPS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, E.J. Factors Associated with Mental Health among International Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, R.H.; Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Mccaffery, K.J.; Pickles, K.; Dodd, R.H.; Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Mccaffery, K.J.; Pickles, K.; et al. Psychological Wellbeing and Academic Experience of University Students in Australia during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plakhotnik, M.S.; Volkova, N.V.; Jiang, C.; Yahiaoui, D.; Pheiffer, G.; McKay, K.; Newman, S.; Reißig-Thust, S. The Perceived Impact of COVID-19 on Student Well-Being and the Mediating Role of the University Support: Evidence From France, Germany, Russia, and the UK. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Value | Total (n = 1598) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| University | VNUA | 291 | 18.2% |

| TBUMP | 1307 | 81.8% | |

| Gender | Female | 1120 | 70.1% |

| Male | 478 | 29.9% | |

| Year of enrollment | First year | 284 | 17.8% |

| Second year | 38 | 2.4% | |

| Third year | 258 | 16.1% | |

| Fourth year | 473 | 29.6% | |

| Fifth year | 418 | 26.2% | |

| Sixth year | 127 | 7.9% | |

| Pre-COVID-19 campus experience | No (first year and second year) | 322 | 20.2% |

| Yes (third year and above) | 1276 | 79.8% | |

| Foreign student | Foreign student | 61 | 3.8% |

| Local student | 1536 | 96.2% | |

| Living status | Alone | 594 | 37.2% |

| With family | 338 | 21.2% | |

| With roommate | 666 | 41.7% | |

| Living place | Dormitory | 235 | 14.7% |

| Rental | 1092 | 68.3% | |

| Home | 271 | 17.0% | |

| Variable | Value | Pre-COVID-19 Campus Experience | Pearson Chi-Square | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 322) | Yes (n = 1276) | Total (n = 1598) | Value (df) | p-Value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Perceived impact on health | Not at all | 103 | 32.0% | 257 | 20.1% | 360 | 22.5% | 24.357 (3) | 0.000 *** |

| Not so much | 153 | 47.5% | 688 | 53.9% | 841 | 52.6% | |||

| Yes, some | 55 | 17.1% | 302 | 23.7% | 357 | 22.3% | |||

| Yes, a lot | 11 | 3.4% | 29 | 2.3% | 40 | 2.5% | |||

| Perceived stress | Not at all | 63 | 19.6% | 158 | 12.4% | 221 | 13.8% | 15.563 (3) | 0.001 ** |

| Not so much | 133 | 41.3% | 542 | 42.5% | 675 | 42.2% | |||

| Yes, some | 100 | 31.1% | 498 | 39.0% | 598 | 37.4% | |||

| Yes, a lot | 26 | 8.1% | 78 | 6.1% | 104 | 6.5% | |||

| Perceived worries | Not at all | 20 | 6.2% | 73 | 5.7% | 93 | 5.8% | 0.430 (3) | 0.934 |

| Not so much | 77 | 23.9% | 288 | 22.6% | 365 | 22.8% | |||

| Yes, some | 157 | 48.8% | 638 | 50.0% | 795 | 49.7% | |||

| Yes, a lot | 68 | 21.1% | 277 | 21.7% | 345 | 21.6% | |||

| Variable | Value | Pre-COVID-19 Campus Experience | Pearson Chi-Square | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 322) | Yes (n = 1276) | Total (n = 1598) | Value (df) | p-Value | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Online class satisfaction | Not at all | 12 | 3.7% | 52 | 4.1% | 64 | 4.0% | 17.326 (3) | 0.001 ** |

| Not so much | 141 | 43.8% | 404 | 31.7% | 545 | 34.1% | |||

| Yes, some | 145 | 45.0% | 719 | 56.3% | 864 | 54.1% | |||

| Yes, a lot | 24 | 7.5% | 101 | 7.9% | 125 | 7.8% | |||

| Online class preference | 0% | 15 | 6.7% | 53 | 4.7% | 68 | 5.0% | 15.362 (4) | 0.004 ** |

| 20% | 67 | 29.8% | 222 | 19.6% | 289 | 21.3% | |||

| 50% | 100 | 44.4% | 583 | 51.4% | 683 | 50.2% | |||

| 80% | 29 | 12.9% | 204 | 18.0% | 233 | 17.1% | |||

| 100% | 14 | 6.2% | 73 | 6.4% | 87 | 6.4% | |||

| Variable | Health | Stress | Worry for Future | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 5.271 (3) | 43.912 *** (3) | 28.700 *** (3) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.153 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Foreign student | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 15.568 ** (3) | 3.755 (3) | 12.581 ** (3) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.001 | 0.289 | 0.006 | |

| n | 1597 | 1597 | 1597 | |

| Female | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 12.607 ** (3) | 18.259 *** (3) | 39.284 *** (3) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Year of enrollment | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 54.396 *** (15) | 36.203 ** (15) | 17.505 (15) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.290 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Pre-COVID-19 campus experience | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 24.357 *** (3) | 15.563 ** (3) | 0.430 (3) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.934 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Living status (alone, with family, or roommates) | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 12.933 * (6) | 19.143 ** (6) | 2.919 (6) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.044 | 0.004 | 0.819 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Living place (dormitory, rental place, home) | Pearson Chi-Square (df) | 8.631 (6) | 11.674 (6) | 4.295 (6) |

| Sig. (2-sided) | 0.195 | 0.070 | 0.637 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Impact on taking classes | Correlation Coefficient | 0.301 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.281 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Online class satisfaction | Correlation Coefficient | −0.058 * | −0.075 ** | −0.028 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.021 | 0.003 | 0.270 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Online class preference | Correlation Coefficient | −0.039 | −0.091 ** | −0.090 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.150 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| n | 1360 | 1360 | 1360 | |

| Impact on research | Correlation Coefficient | 0.329 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.252 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Impact on meal and shopping | Correlation Coefficient | 0.487 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.235 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Impact on daily life | Correlation Coefficient | 0.489 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.395 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Income change | Correlation Coefficient | −0.054 * | −0.052 * | −0.080 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.031 | 0.037 | 0.001 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Life plan change | Correlation Coefficient | 0.330 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.435 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | |

| Access to information | Correlation Coefficient | −0.012 | 0.112 ** | 0.217 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.622 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 |

| Factor Loadings | Impacts on Well-Being | Impacts on Campus Life | Online Preference | Income and Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived stress | 0.850 | |||

| Worry about future | 0.773 | |||

| Perceived health impact | 0.773 | |||

| Daily life | 0.799 | |||

| Meals and shopping | 0.718 | |||

| Research | 0.662 | |||

| Taking classes | 0.645 | |||

| Life plan change | 0.636 | |||

| Online satisfaction | 0.790 | |||

| Best amount online | 0.684 | |||

| Income change | 0.715 | |||

| Access to information | 0.592 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, N.H.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, B.T.; Phan, Q.N. Students’ Perceived Well-Being and Online Preference: Evidence from Two Universities in Vietnam during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912129

Tran NH, Nguyen NT, Nguyen BT, Phan QN. Students’ Perceived Well-Being and Online Preference: Evidence from Two Universities in Vietnam during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(19):12129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912129

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Nam Hoang, Nhien Thi Nguyen, Binh Thanh Nguyen, and Quang Ngoc Phan. 2022. "Students’ Perceived Well-Being and Online Preference: Evidence from Two Universities in Vietnam during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19: 12129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912129

APA StyleTran, N. H., Nguyen, N. T., Nguyen, B. T., & Phan, Q. N. (2022). Students’ Perceived Well-Being and Online Preference: Evidence from Two Universities in Vietnam during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912129