Exploring the Multidimensional Participation of Adults Living in the Community in the Chronic Phase following Acquired Brain Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

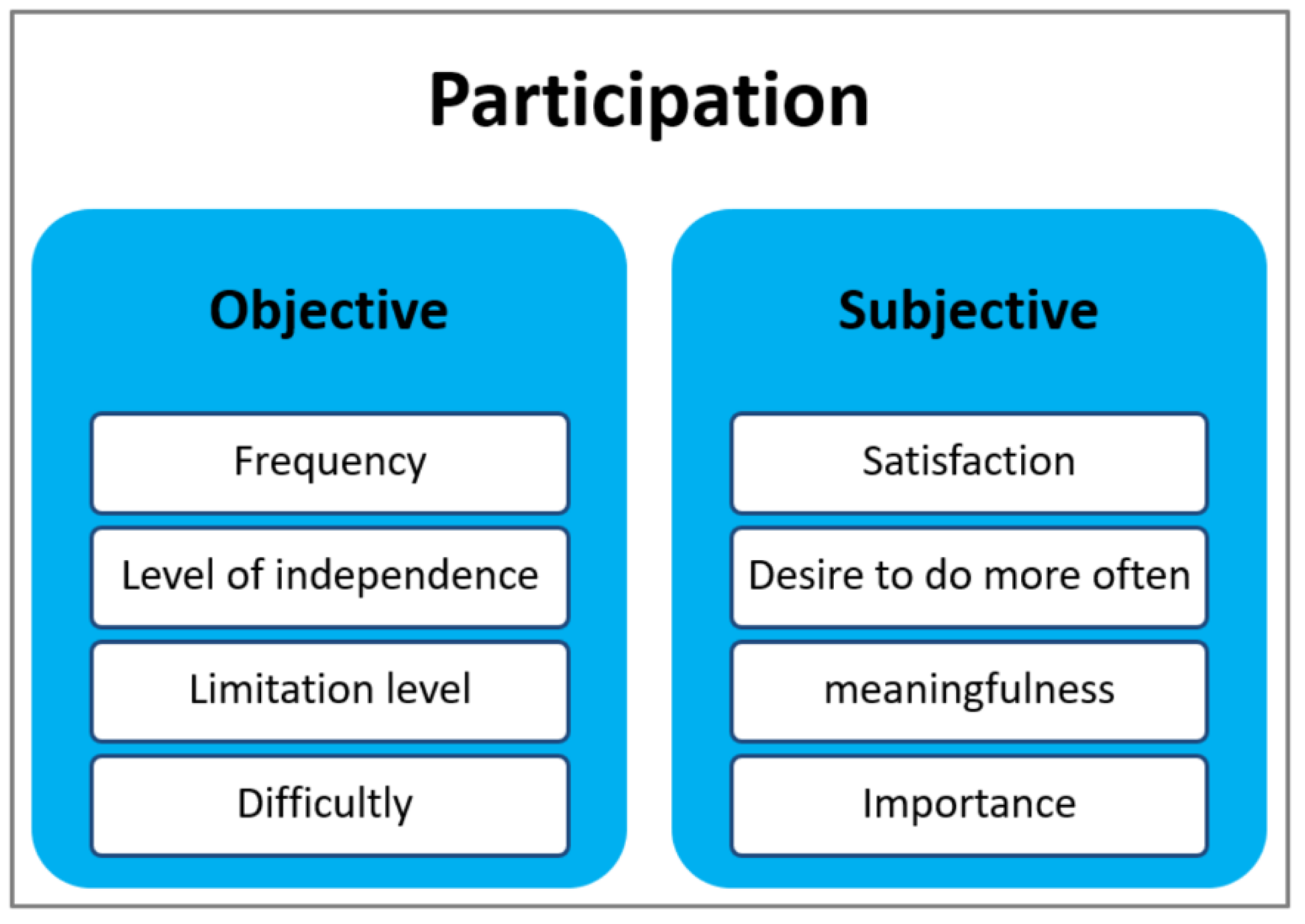

2.3.2. Participation Measures

2.3.3. Environmental Factor: Perceived Accessibility

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

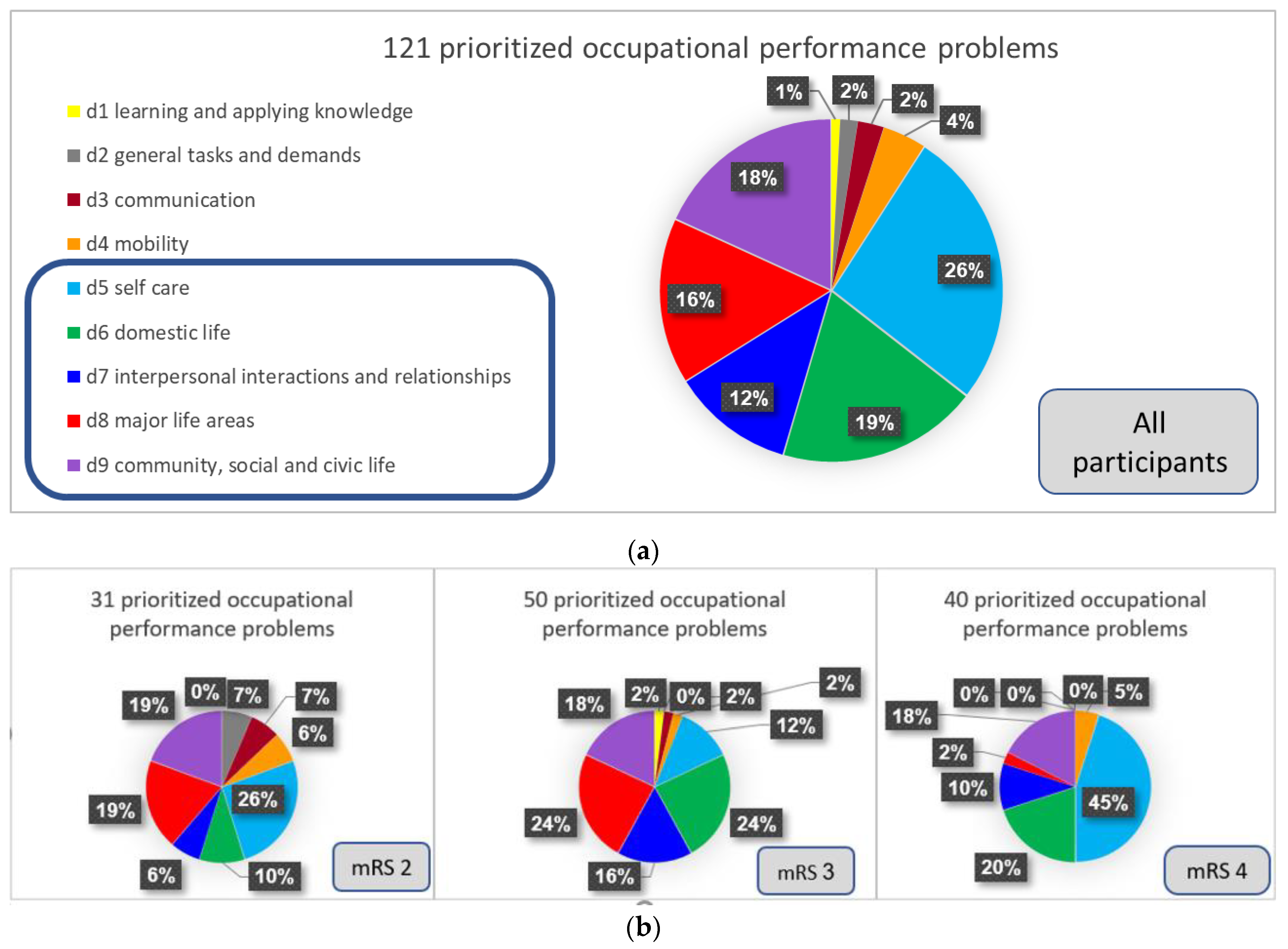

3.2. Subjective Participation According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Terminology

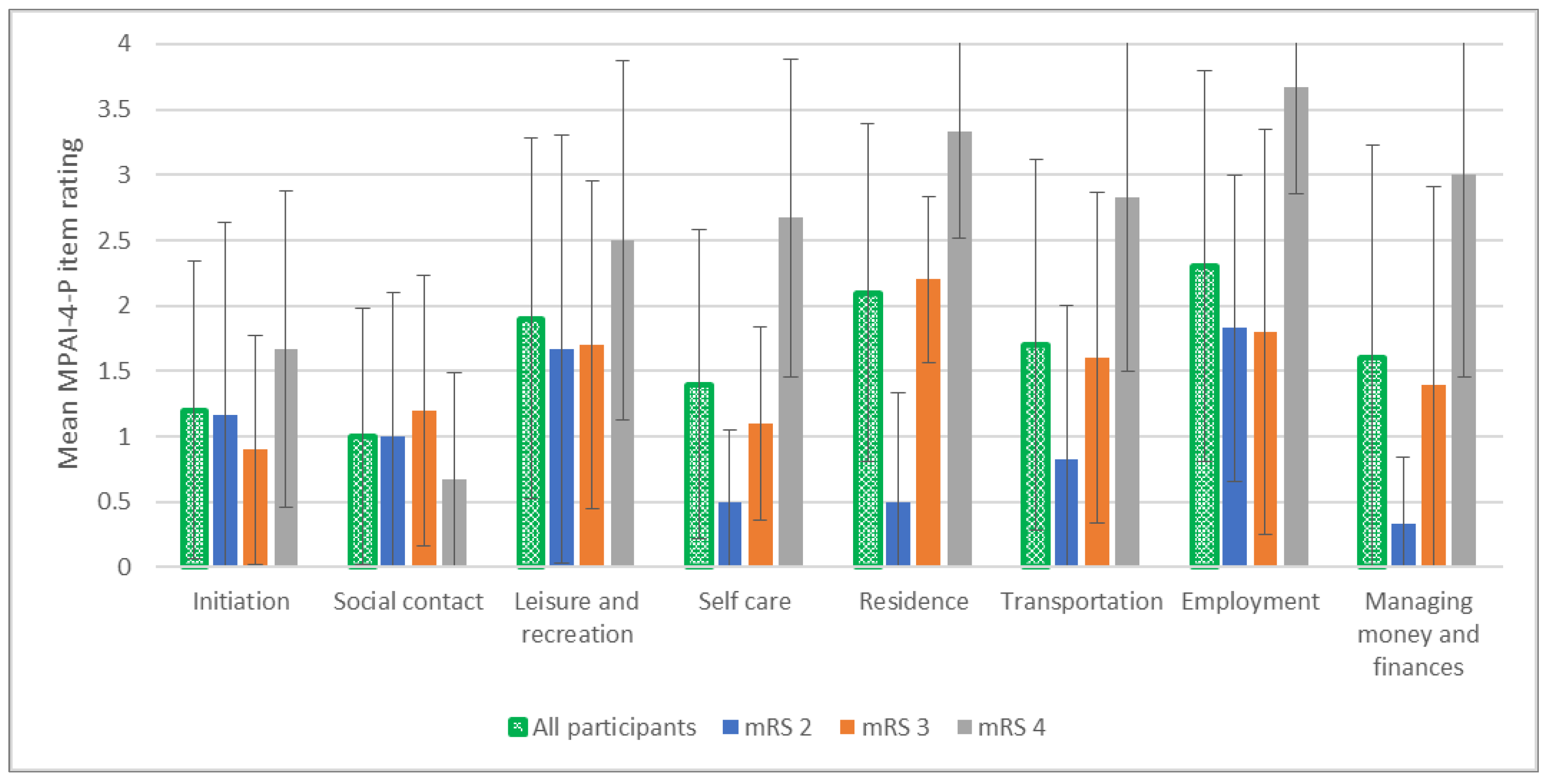

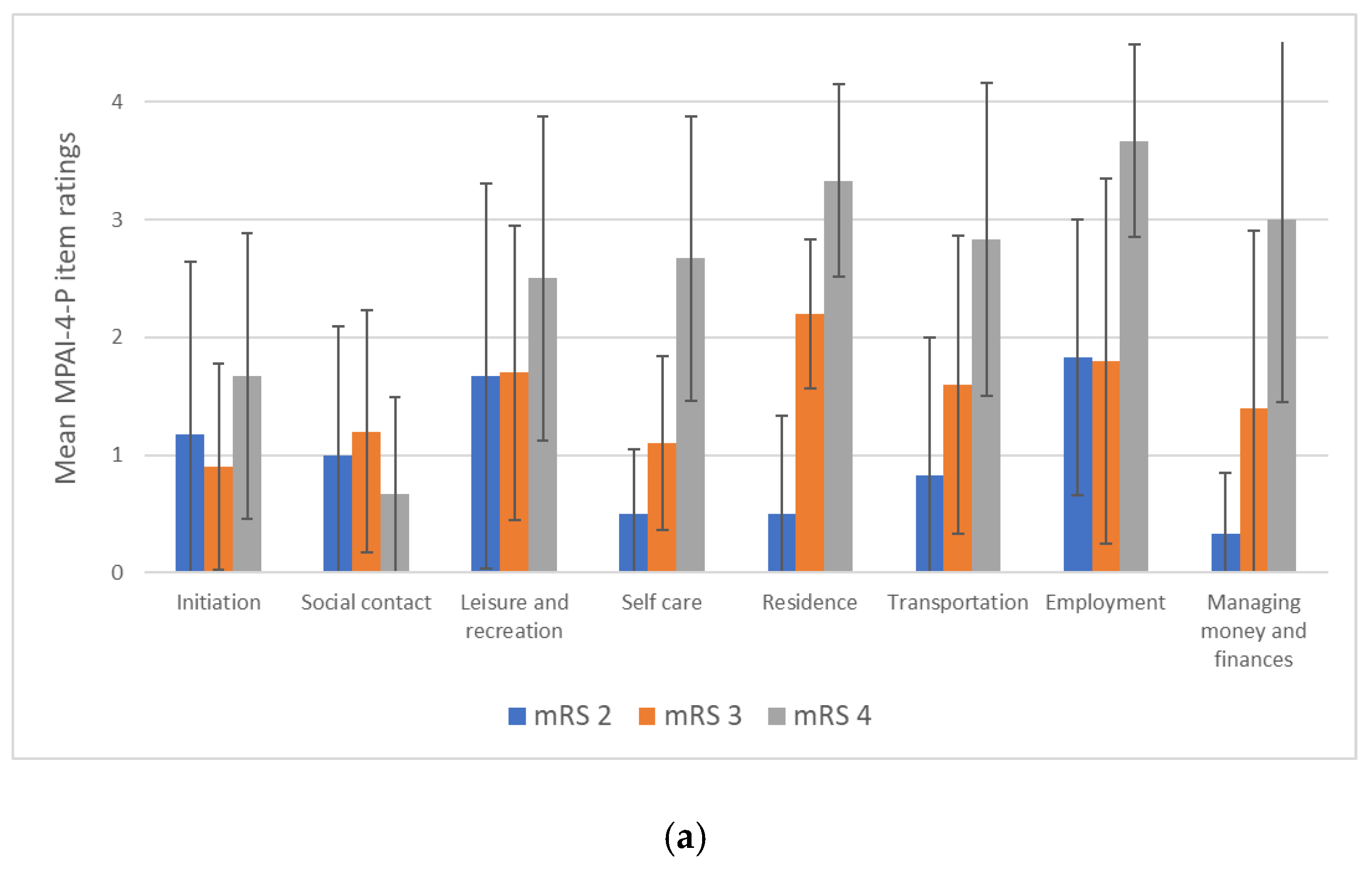

3.3. Objective Participation

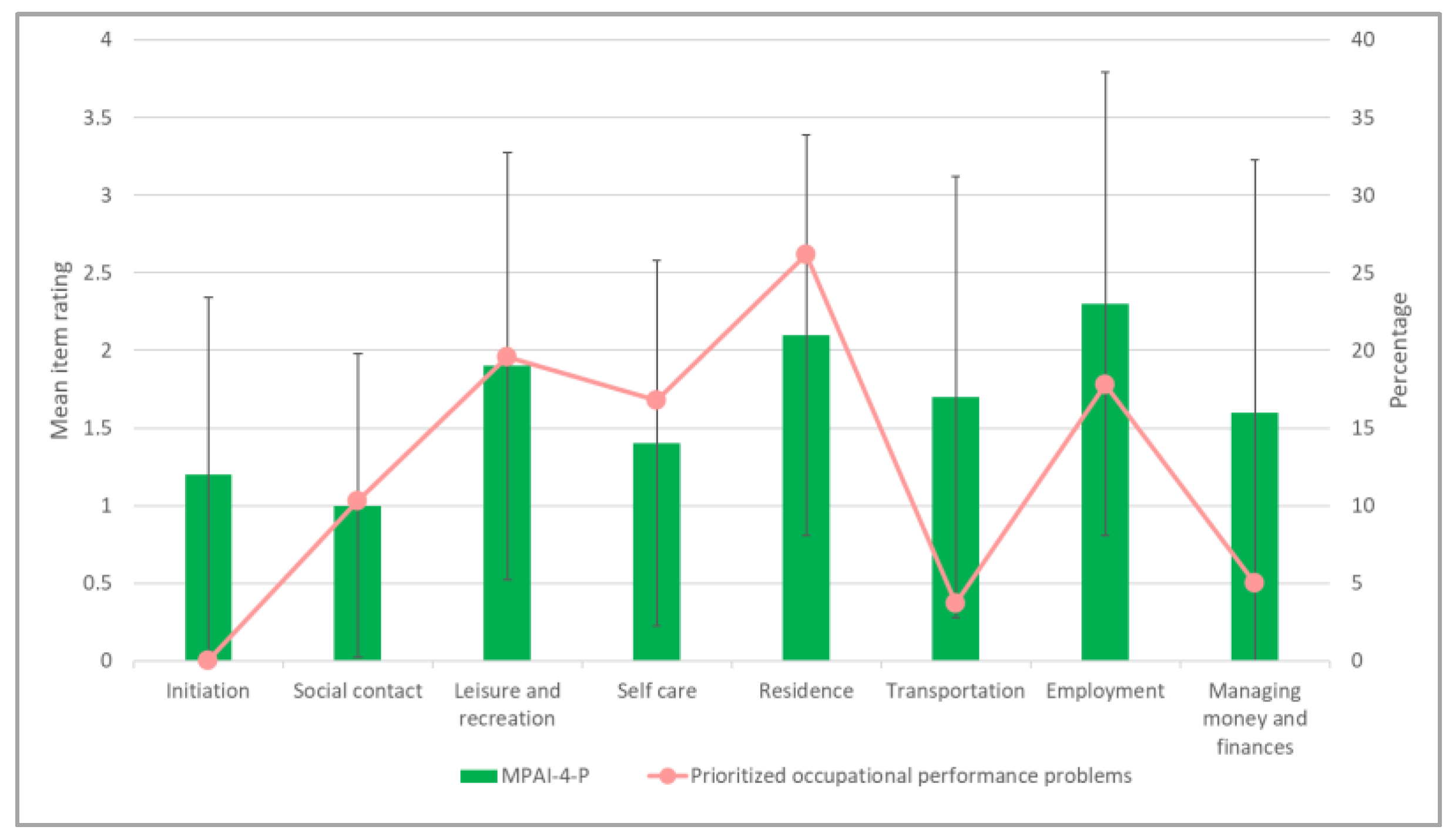

3.4. Exploration of the Compatibility of the Objective and Subjective Aspects of Participation

3.5. Exploration of the Relationship between the Perceived Environmental Accessibility and the Different Aspects of Participation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ICF Code and Category | Number of Problems | % |

|---|---|---|

| Chapter 1: Learning and applying knowledge | 1 | 0.8% |

| d170: Writing | 1 | 0.8% |

| Chapter 2: General tasks and demands | 2 | 1.7% |

| d230: Carrying out daily routine | 2 | 1.7% |

| Chapter 3: Communication | 3 | 2.5% |

| d360: Using communication devices and techniques | 2 | 1.7% |

| d350: Conversation | 1 | 0.8% |

| Chapter 4: Mobility | 5 | 4.1% |

| d475: Driving | 3 | 2.5% |

| d460: Moving around in different locations | 1 | 0.8% |

| d410: Changing basic body position | 1 | 0.8% |

| Chapter 5: Self-care | 32 | 26.5% |

| d570: Looking after one’s health | 13 | 10.7% |

| d540: Dressing | 8 | 6.6% |

| d510: Washing oneself | 6 | 5.0% |

| d550: Eating | 3 | 2.5% |

| d520: Caring for body parts | 2 | 1.7% |

| Chapter 6: Domestic life | 23 | 19% |

| d640: Doing housework | 4 | 3.3% |

| d620: Acquisition of goods and services | 4 | 3.3% |

| d630: Preparing meals | 12 | 9.9% |

| d650: Caring for household objects | 3 | 2.5% |

| Chapter 7: Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 14 | 11.5% |

| d760: Family relationships | 10 | 8.2% |

| d770: Intimate relationships | 3 | 2.5% |

| d750: Informal social relationships | 1 | 0.8% |

| Chapter 8: Major life areas | 19 | 15.7% |

| d850: Remunerative employment | 7 | 5.8% |

| d845: Acquiring, keeping and terminating a job | 3 | 2.5% |

| d855: Non-remunerative employment | 7 | 5.8% |

| d860: Basic economic transactions | 1 | 0.8% |

| d865: Complex economic transactions | 1 | 0.8% |

| Chapter 9: Community, social and civic life | 22 | 18.2% |

| d920: Recreation and leisure | 16 | 13.2% |

| d910: Community life | 4 | 3.3% |

| d930: Religion and spirituality | 2 | 1.7% |

| Total | 121 | 100% |

References

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, K.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Hendrikx, A.; Abma, T.A. Participation of people with acquired brain injury: Insiders perspectives. Brain Inj. 2011, 25, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, W.; Fischer, S. Participation limitations following acquired brain damage: A pilot study on the relationship among functional disorders as well as personal and environmental context factors. Die Rehabil. 2008, 47, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammel, J.; Magasi, S.; Heinemann, A.; Gray, D.B.; Stark, S.; Kisala, P.; Carlozzi, N.E.; Tulsky, D.; Garcia, S.F.; Hahn, E.A. Environmental barriers and supports to everyday participation: A qualitative insider perspective from people with disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maritz, R.; Baptiste, S.; Darzins, S.W.; Magasi, S.; Weleschuk, C.; Prodinger, B. Linking occupational therapy models and assessments to the ICF to enable standardized documentation of functioning. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 85, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.M.; Corrêa, J.C.F.; Pereira, G.S.; Corrêa, F.I. Social participation following a stroke: An assessment in accordance with the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömer, A.M.V.; Van Mierlo, M.L.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Van Heugten, C.M.; Post, M.W. Does the frequency of participation change after stroke and is this change associated with the subjective experience of participation? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.H.; Coster, W.J.; Helfrich, C.A. Community participation measures for people with disabilities: A systematic review of content from an international classification of functioning, disability and health perspective. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zee, C.H.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Lindeman, E.; Jaap Kappelle, L.; Post, M.W. Participation in the chronic phase of stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2013, 20, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghifard, M.; Taghizadeh, G.; Akbarfahimi, M.; Eakman, A.M.; Hosseini, S.H.; Azad, A. Psychometric properties of Meaningful Activity Participation Assessment (MAPA) in chronic stroke survivors. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2021, 28, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toglia, J.; Askin, G.; Gerber, L.M.; Jaywant, A.; O’Dell, M.W. Participation in younger and older adults post-stroke: Frequency, importance, and desirability of engagement in activities. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammel, J.; Magasi, S.; Heinemann, A.; Whiteneck, G.; Bogner, J.; Rodriguez, E. What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2008, 30, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel-Yeger, B.; Tse, T.; Josman, N.; Baum, C.; Carey, L.M. Scoping review: The trajectory of recovery of participation outcomes following stroke. Behav. Neurol. 2018, 2018, 5472018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepo, I.; Sangster Jokić, C.; Tršinski, D. The role of occupational participation for people with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of the literature. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 44, 2988–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannoo, E.; Brusselmans, W.; Eynde, L.V.; Van Laere, M.; Stevens, J. Epidemiology of acquired brain injury (ABI) in adults: Prevalence of long-term disabilities and the resulting needs for ongoing care in the region of Flanders, Belgium. Brain Inj. 2004, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciuffreda, K.J.; Kapoor, N. Acquired brain injury. In Visual Diagnosis and Care of the Patient with Special Needs; Taub, M.B., Bartuccio, M., Maino, D.M., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Andelic, N.; Howe, E.I.; Hellstrøm, T.; Sanchez, M.F.; Lu, J.; Løvstad, M.; Røe, C. Disability and quality of life 20 years after traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, e01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, J.; Schepers, V.; Nijsse, B.; van Heugten, C.; Post, M.W.; Visser-Meily, J. The influence of psychological factors and mood on the course of participation up to four years after stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, J.F.d.; Morelato, R.L.; Pinto, H.P.; Oliveira, E.R.A.d. Disability after stroke: A systematic review. Fisioter. Mov. 2015, 28, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverover, Y.; Genova, H.; Smith, A.; Chiaravalloti, N.; Lengenfelder, J. Changes in activity participation following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2017, 27, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipskaya-Velikovsky, L.; Zeilig, G.; Weingarden, H.; Rozental-Iluz, C.; Rand, D. Executive functioning and daily living of individuals with chronic stroke: Measurement and implications. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2018, 41, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Trabelsi, K.; Masmoudi, L.; Brach, M.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COVID-19 home confinement negatively impacts social participation and life satisfaction: A worldwide multicenter study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.K.; Lee, H.S.; Park, H.Y. Convergence study on the impact of COVID-19 on the occupational performance area of adults. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2021, 12, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverover, Y.; Kim, G.; Chen, M.H.; Volebel, G.T.; Rosenfeld, M.; Botticello, A.; DeLuca, J.; Genova, H.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on engagement in activities of daily living in persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.L.; von Koch, L.; Andersson, M.; Tham, K.; Eriksson, G. Participation in everyday life and life satisfaction in persons with stroke and their caregivers 3–6 months after onset. J. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 47, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.Y. Determinants of the health-related quality of life for stroke survivors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015, 24, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, G.J.; Gargaro, J.; McMackin, S. Community integration and health-related quality-of-life following acquired brain injury for persons living at home. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.M.; Perera, S.; Duncan, P.W.; Bode, R. Physical and social functioning after stroke: Comparison of the Stroke Impact Scale and Short Form-36. Stroke 2003, 34, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadidi, V.; Katz-Leurer, M.; Carmeli, E.; Bornstein, N.M. Long-term outcome poststroke: Predictors of activity limitation and participation restriction. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1802–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, D.P.J.; Post, M.W.M.; Köhler, S.; Carey, L.M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; van Heugten, C.M. Course of social participation in the first 2 years after stroke and its associations with demographic and stroke-related factors. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2018, 32, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditchman, N.; Sheehan, L.; Rafajko, S.; Haak, C.; Kazukauskas, K. Predictors of social integration for individuals with brain injury: An application of the ICF model. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersey, J.; McCue, M.; Skidmore, E. Domains and dimensions of community participation following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2020, 34, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellema, S.; van der Sande, R.; van Hees, S.; Zajec, J.; Steultjens, E.M.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W. Role of environmental factors on resuming valued activities poststroke: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative findings. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 991–1002.e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Vecchia, C.; Viprey, M.; Haesebaert, J.; Termoz, A.; Giroudon, C.; Dima, A.; Rode, G.; Préau, M.; Schott, A.M. Contextual determinants of participation after stroke: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 1786–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman-Maeir, A.; Soroker, N.; Ring, H.; Avni, N.; Katz, N. Activities, participation and satisfaction one-year post stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrosiers, J.; Demers, L.; Robichaud, L.; Vincent, C.; Belleville, S.; Ska, B. Short-Term changes in and predictors of participation of older adults after stroke following acute care or rehabilitation. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2008, 22, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singam, A.; Ytterberg, C.; Tham, K.; von Koch, L. Participation in complex and social everyday activities six years after stroke: Predictors for return to pre-stroke level. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M.; Brewer, M.; Wolf, T. The impact of mild stroke on participation in physical fitness activities. Stroke Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 548682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.F.; Hahn, M.; Baum, C.; Dromerick, A.W. The Impact of mild stroke on meaningful activity and life satisfaction. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2006, 15, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelros, P. Characteristics of the Frenchay Activities Index one year after a stroke: A population-based study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, G.; Aasnes, M.; Tistad, M.; Guidetti, S.; von Koch, L. Occupational gaps in everyday life one year after stroke and the association with life satisfaction and impact of stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2012, 19, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palstam, A.; Sjödin, A.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Participation and autonomy five years after stroke: A longitudinal observational study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsford, J.L.; Downing, M.G.; Olver, J.; Ponsford, M.; Acher, R.; Carty, M.; Spitz, G. Longitudinal follow-up of patients with traumatic brain injury: Outcome at two, five, and ten years post-injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, J.A.; van Mierlo, M.L.; Post, M.W.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Kappelle, L.J.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A. Long-term restrictions in participation in stroke survivors under and over 70 years of age. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norlander, A.; Jönsson, A.C.; Ståhl, A.; Lindgren, A.; Iwarsson, S. Activity among long-term stroke survivors. A study based on an ICF-oriented analysis of two established ADL and social activity instruments. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, T.F.; de Melo, L.P.; Dantas, A.A.T.S.G.; de Oliveira, D.C.; Oliveira, R.A.N.d.S.; Cordovil, R.; Silveira Fernandes, A.B.G. Functional activities habits in chronic stroke patients: A perspective based on ICF framework. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 45, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paanalahti, M.; Murphy, M.A.; Lundgren-Nilsson, Å.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Validation of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for stroke by exploring the patient’s perspective on functioning in everyday life: A qualitative study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2014, 37, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riberto, M.; Lopes, K.A.T.; Chiappetta, L.M.; Lourenção, M.I.P.; Battistella, L.R. The use of the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core set for stroke for chronic outpatients in three Brazilian rehabilitation facilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, C.; Bolis, M.; Limonta, M.; Meroni, R.; Ostasiewicz, K.; Cornaggia, C.M.; Alouche, S.R.; da Silva Matuti, G.; Cerri, C.G.; Piscitelli, D. Differences in rehabilitation needs after stroke: A similarity analysis on the ICF core set for stroke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.; Fary, K.; Judson, R. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Sets for traumatic brain injury from Australian community patient perspectives. J. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 53, jrm00218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistarini, C.; Aiachini, B.; Coenen, M.; Pisoni, C. Functioning and disability in traumatic brain injury: The Italian patient perspective in developing ICF Core Sets. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 2333–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin Kew, C.; Juengst, S.; Erler, K. Differences in meaningful participation across the lifespan among individuals with chronic traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.V.; Goverover, Y.; Dijkers, M. Community activities and individuals’ satisfaction with them: Quality of life in the first year after traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooker, S.A.; Masters, K.S.; Vagnini, K.M.; Rush, C.L. Engaging in personally meaningful activities is associated with meaning salience and psychological well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, M.; Davis, C.G.; Dubouloz, C.J.; Kessler, D.; Kubina, L.A. Participation and well-being poststroke: Evidence of reciprocal effects. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, G.; Baum, M.C.; Wolf, T.J.; Connor, L.T. Perceived participation after stroke: The influence of activity retention, reintegration, and perceived recovery. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, e131–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogan, A.M.; Carlson, M. Deciphering participation: An interpretive synthesis of its meaning and application in rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2692–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit Yosef, A.; Jacobs, J.M.; Shenkar, S.; Shames, J.; Schwartz, I.; Doryon, Y.; Naveh, Y.; Khalailh, F.; Berrous, S.; Gilboa, Y. Activity performance, participation, and quality of life among adults in the chronic stage after acquired brain injury-The feasibility of an occupation-based telerehabilitation Intervention. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit Yosef, A.; Jacobs, J.M.; Shames, J.; Schwartz, I.; Gilboa, Y. A performance-based teleintervention for adults in the chronic stage after acquired brain injury: An exploratory pilot randomized controlled crossover study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Rao, V.A.; Heilman-Espinoza, E.R.; Lai, R.; Quesada, R.A.; Flint, A.C. Simple and reliable determination of the modified rankin scale score in neurosurgical and neurological patients: The mRS-9Q. Neurosurgery 2012, 71, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; Fanjiang, G. Mini-Mental State Examination: Clinical Guide; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bedirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepacz, P.T.; Hochstetler, H.; Wang, S.; Walker, B.; Saykin, A.J. Relationship between the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-mental State Examination for assessment of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, J.M.; Hammerman-Rozenberg, A.; Stessman, J. Frequency of leaving the house and mortality from Age 70 to 95. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornstein, K.A.; Leff, B.; Covinsky, K.E.; Ritchie, C.S.; Federman, A.D.; Roberts, L.; Kelley, A.S.; Siu, A.L.; Szanton, S.L. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.A.; Evans, J.J.; Emslie, H.; Alderman, N.; Burgess, P. The development of an ecologically valid test for assessing patients with a dysexecutive syndrome. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 1998, 8, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, D.H.; Spikman, J.M.; Rietveld, A.C.; Fasotti, L. Executive dysfunction in chronic brain-injured patients: Assessment in outpatient rehabilitation. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2009, 19, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azouvi, P.; Vallat-Azouvi, C.; Millox, V.; Darnoux, E.; Ghout, I.; Azerad, S.; Ruet, A.; Bayen, E.; Pradat-Diehl, P.; Aegerter, P. Ecological validity of the dysexecutive questionnaire: Results from the PariS-TBI study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2015, 25, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, P.W.; Alderman, N.; Evans, J.; Emslie, H.; Wilson, B.A. The ecological validity of tests of executive function. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1998, 4, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.C.; Baptiste, S.; Carswell, A.; McColl, M.A.; Polatajko, H.; Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: COPM, 5th ed.; CAOT Publ. ACE: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014.

- Yang, S.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Chang, J.H. The Canadian occupational performance measure for patients with stroke: A systematic review. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cup, E.H.C.; Scholte op Reimer, W.J.M.; Thijssen, M.C.E.; van Kuyk-Minis, M.A.H. Reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in stroke patients. Clin. Rehabil. 2003, 17, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, S.; Richardson, P. Occupational therapy outcomes for clients with traumatic brain injury and stroke using the canadian occupational performance measure. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 61, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kean, J.; Malec, J.F.; Altman, I.M.; Swick, S. Rasch measurement analysis of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4) in a community-based rehabilitation sample. J. Neurotrauma 2011, 28, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malec, J.F.; Lezak, M.D. Manual for the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4) for Adults, Children and Adolescents. 2008. Available online: http://www.tbims.org/combi/mpai/manual.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- Guerrette, M.-C.; McKerral, M. Validation of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4 (MPAI-4) and reference norms in a French-Canadian population with traumatic brain injury receiving rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malec, J.F.; Kean, J.; Altman, I.M.; Swick, S. Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory: Comparing psychometrics in cerebrovascular accident to traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 2271–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.M.; Swick, S.; Parrot, D.; Malec, J.F. Effectiveness of community-based rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury for 489 program completers compared with those precipitously discharged. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher, V.; Murphy, M.P.; Murphy, T.F.; Malec, J.F. Progress assessed with the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory in 604 participants in 4 types of post–inpatient rehabilitation brain injury programs. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Geyh, S.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Ustün, B.; Stucki, G. ICF linking rules: An update based on lessons learned. J. Rehabil. Med. 2005, 37, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatajko, H.J.; McEwen, S.E.; Ryan, J.D.; Baum, C.M. Pilot randomized controlled trial investigating cognitive strategy use to improve goal performance after stroke. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg-Shpigelman, S.; Bar-Haim Erez, A.; Nahaloni, I.; Maeir, A. Neurofunctional treatment targeting participation among chronic stroke survivors: A pilot randomised controlled study. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, K.J.; Birkenmeier, R.L.; Bland, M.D.; Lang, C.E. An exploratory analysis of the self-reported goals of individuals with chronic upper-extremity paresis following stroke. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, C.D. Responsiveness of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure for adults with ABI. Int. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 3, 1000267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.W.; Bode, R.K.; Lai, S.M.; Perera, S.; Investigators, G.A.i.N.A. Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: The stroke impact scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.M.; van der Zee, C.H.; Hennink, J.; Schafrat, C.G.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; van Berlekom, S.B. Validity of the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, A.W.; Lai, J.S.; Magasi, S.; Hammel, J.; Corrigan, J.D.; Bogner, J.A.; Whiteneck, G.G. Measuring Participation Enfranchisement. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, M.; Wiseman, L.; Seymour, T.; Pike, S.; Cuming, T.; Wall, G. Stroke self-management and the role of self-efficacy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satink, T.; Cup, E.H.C.; de Swart, B.J.M.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G. Self-management: Challenges for allied healthcare professionals in stroke rehabilitation—A focus group study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, F.; Riazi, A.; Norris, M. Self-management after stroke: Time for some more questions? Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.; Park, H.Y. Developing domains and items about self-management among elderly people with chronic disease. Healthcare 2022, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, C.E.; Rojas-Líbano, D.; Castro, O.; Cruces, R.; Evans, J.; Radovic, D.; Arévalo-Romero, C.; Torres, J.; Aliaga, Á. Social isolation after acquired brain injury: Exploring the relationship between network size, functional support, loneliness and mental health. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Walker, I.; Sauvé-Schenk, K.; Egan, M. Goal setting dynamics that facilitate or impede a client-centered approach. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bailón, M.; López-González, L.; Merchán-Baeza, J.A. Client-centred practice in occupational therapy after stroke: A systematic review. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 29, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, S.; Evans, N.; Huisman, M.; Welch Saleeby, P.; Widdershoven, G. Toward a paradigm shift in healthcare: Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the capability approach (CA) jointly in theory and practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, B.M.; Buchbinder, R.; Beaton, D.E. A study compared nine patient-specific indices for musculoskeletal disorders. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamit, T.; Maeir, A.; Ben Assayag, E.; Bornstein, N.M.; Korczyn, A.D.; Katz, N. Impact of first-ever mild stroke on participation at 3 and 6 month post-event: The TABASCO study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD (Range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.84 ± 10.70 (35-79) |

| Sex Female Male | 10 (40%) 15 (60%) |

| Years of education | 13 ± 3.55 (2–19) |

| Marital status Married Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 20 (80%) 5 (20%) |

| Living area Urban Rural | 22 (88%) 3 (12%) |

| Employment status post-ABI Full/Part-time work Retirement/Volunteering Unemployment | 6 (24%) 13 (52%) 6 (24%) |

| ABI type Ischemic stroke Hemorrhagic stroke Traumatic brain injury | 17 (68%) 6 (24%) 2 (8%) |

| ABI side Right Left Bilateral | 14 (56%) 10 (40%) 1 (4%) |

| Time since ABI (months) | 9.44 ± 2.95 (6–18) |

| mRS scores Score 2—Slight disability Score 3—Moderate disability Score 4—Moderately severe disability | 3.04 ± 0.79 (2–4) 7 (28%) 10 (40%) 8 (32%) |

| Depression * No Yes | 13 (62%) 8 (38%) |

| DEX * | 15.67 ± 12.84 (0–46) |

| Walking aid No Yes | 12 (48%) 13 (52%) |

| Mobility outside by foot post-ABI Yes No | 19 (76%) 6 (24%) |

| Mobility by car post-ABI Driver Passenger No car | 8 (32%) 14 (56%) 3 (12%) |

| Frequency of leaving the house Daily or nearly daily (6–7 times a week) Often (2–5 times a week) Rarely (≤1 time a week) | 11 (44%) 10 (40%) 4 (16%) |

| Perceived accessibility of the environment Home environment Community environment | 8.88 ± 1.36 (6–10) 7.38 ± 2.07 (4–10) |

| COPM-Occupational Problem | ICF 1st-Level Domain | ICF 2nd-Level Domain | ICF 3rd-Level Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Write more clearly | d1. Learning and applying knowledge | d170. Writing | d1708. Writing clearly |

| Get organized in the morning at a faster pace | d2. General tasks and demands | d230. Carrying out daily routine | d2303. Managing one’s own activity level |

| Maintain my concentration during a conversation | d3. Communication | d350. Conversation | d3501. Sustaining a conversation |

| Getting back to riding my bicycle every day | d4. Mobility | d475. Driving | d4750. Driving human-powered transportation |

| Start going to a weekly exercise class again | d5. Self-care | d570. Looking after one’s health | d5701. Managing diet and fitness |

| Put on my pants independently | d5. Self-care | d540. Dressing | d5400. Putting on clothes |

| Being able to care for my dog more independently at home | d6. Domestic life | d650. Caring for household objects | d6506. Taking care of animals |

| Participate in weekly leisure activities with my children | d7. Interpersonal interactions and relationships | d760. Family relationships | d7600. Parent-child relationships |

| Return to work | d8. Major life areas | d845. Acquiring, keeping, and terminating a job | d8451. Maintaining a job |

| Learn how to track my bank account online | d8. Major life areas | d870. Economic self-sufficiency | d8700. Personal economic resources |

| Get back to reading books every day | d9. Community, social and civic life | d920. Recreation and leisure | d9202. Arts and culture |

| Get back to visiting the community center a few times a week | d9. Community, social and civic life | d910. Community life | d9100. Informal associations |

| Objective Participation (N = 22) | Subjective Participation (N = 25) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPAI-4-P | COPM-Performance | COPM-Satisfaction | |||||

| rs | p | rs | p | rs | p | ||

| Perceived environmental accessibility (N = 22) | Home | −0.474 * | 0.026 | −0.065 | 0.757 | −0.146 | 0.485 |

| Community | −0.464 * | 0.030 | 0.056 | 0.790 | 0.166 | 0.429 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beit Yosef, A.; Refaeli, N.; Jacobs, J.M.; Shames, J.; Gilboa, Y. Exploring the Multidimensional Participation of Adults Living in the Community in the Chronic Phase following Acquired Brain Injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811408

Beit Yosef A, Refaeli N, Jacobs JM, Shames J, Gilboa Y. Exploring the Multidimensional Participation of Adults Living in the Community in the Chronic Phase following Acquired Brain Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811408

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeit Yosef, Aviva, Nirit Refaeli, Jeremy M. Jacobs, Jeffrey Shames, and Yafit Gilboa. 2022. "Exploring the Multidimensional Participation of Adults Living in the Community in the Chronic Phase following Acquired Brain Injury" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811408

APA StyleBeit Yosef, A., Refaeli, N., Jacobs, J. M., Shames, J., & Gilboa, Y. (2022). Exploring the Multidimensional Participation of Adults Living in the Community in the Chronic Phase following Acquired Brain Injury. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811408