Special Education Teachers: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in the Relationship between Teachers’ Efficacy for Inclusive Practice and Teaching Styles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Correlations

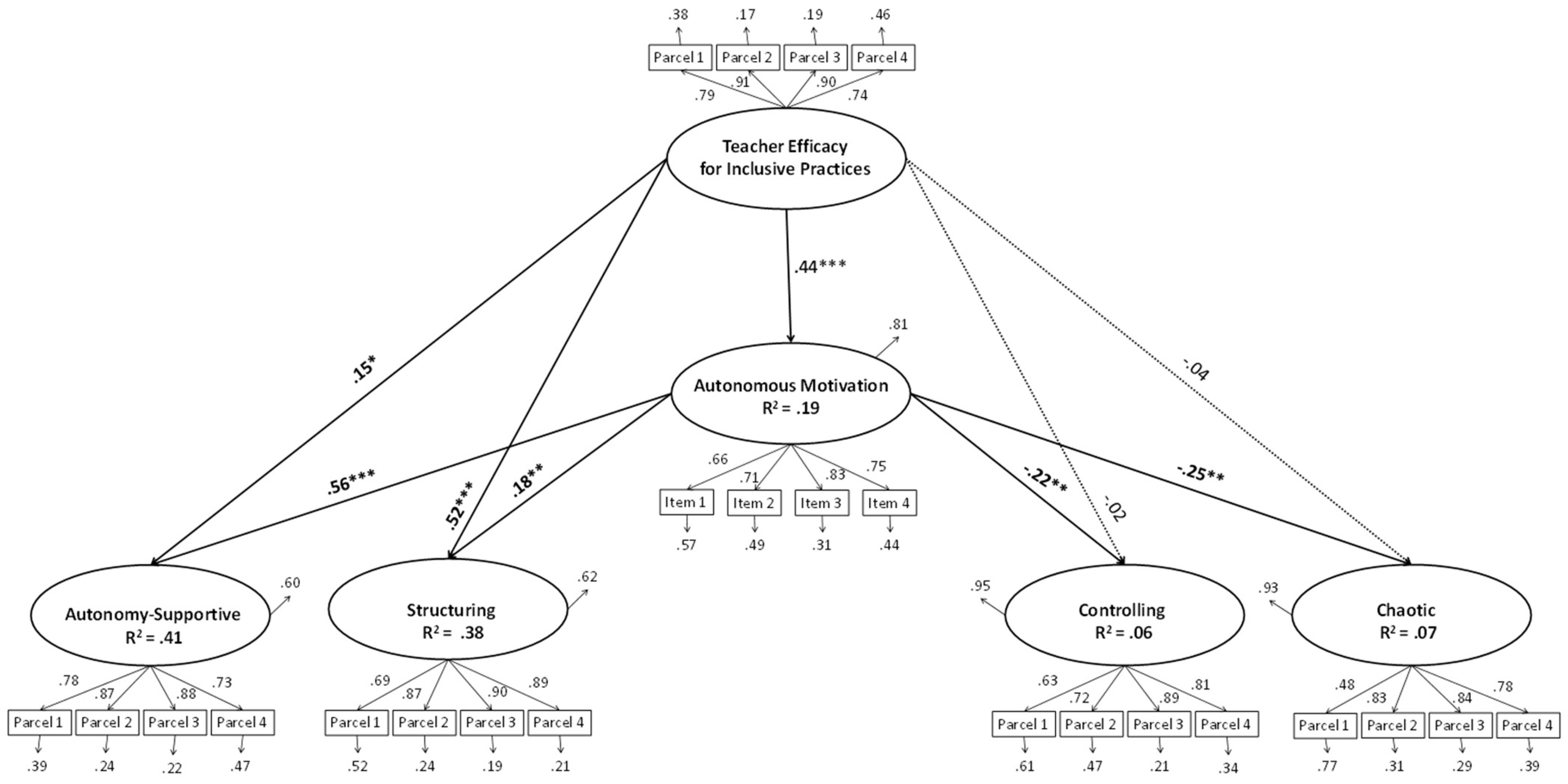

3.2. SEM Analysis

4. Conclusions

4.1. Study Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Practical Implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia, R.M.C. Educação especial na perspectiva inclusiva: Determinantes econômicos e políticos [Special education at inclusive perspective: Economic and politics determinants]. Comunicações 2016, 23, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzuneck, J.A. Crenças de autoeficácia de professores: Um fator motivacional crítico na educação inclusiva [Teacher self-efficacy beliefs: A critical motivational factor in inclusive education]. Rev. Educ. Espec. 2017, 30, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Worth: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 187–200. ISBN 9780716726265. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.; Loreman, T.; Forlin, C. Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2012, 12, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, L.P. Self-Efficacy of the University Professor: Efficacy Perceived and Teaching Practice, 2nd ed.; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-8427715486. [Google Scholar]

- De Charms, R. Personal Causation: The Internal Affective Determinants of Behavior; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 9781315825632. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.A.; Passanisi, A. When intensions do not map onto extensions: Individual differences in conceptualization. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2016, 42, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hand, M. Against autonomy as an educational aim. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2006, 32, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Fontán, E.; García-Señorán, M.; Conde-Rodríguez, Á.; González, A. Teachers’ ICT-related self-efficacy, job resources, and positive emotions: Their structural relations with autonomous motivation and work engagement. Comp. Educ. 2019, 134, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghsh, Z.; Aghaeinejad, N. The mediating role of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic responsibility. Rooyesh E Ravanshenasi J. 2022, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, F.; Aşkun, D. The effect of occupational self-efficacy on work performance through intrinsic work motivation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 41, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, S.N.; Fortier, M.S.; Strachan, S.M.; Blanchard, C.M. Testing and integrating self-determination theory an self-efficacy theory in a physical activity context. Can. Psychol. 2012, 53, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; Berger, J.L. Linking teacher self-efficacy and responsibility with teachers’ self-reported and student-reported motivating styles and student engagement. Learn. Instr. 2021, 76, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Haerens, L.; Soenens, B.; Fontaine, J.R.; Reeve, J. Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, G.; Lo Cascio, V.; Pace, U. The role of individual and relational characteristics on alcohol consumption among Italian adolescents: A discriminant function analysis. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, C.; Filippello, P.; Caparello, C.; Sorrenti, L. Need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviors by teachers and classmates in adolescence: The mediating role of basic psychological needs on school alienation and academic achievement. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseth, Å.; Breidablik, H.J.; Meland, E. Longitudinal relations between perceived autonomy support and basic need satisfaction in two student cohorts. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P.; Buzzai, C.; Costa, S.; Orecchio, S.; Sorrenti, L. Teaching style and academic achievement: The mediating role of learned helplessness and mastery orientation. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippello, P.; Buzzai, C.; Costa, S.; Sorrenti, L. School refusal and absenteeism: Perception of teacher behaviors, psychological basic needs, and academic achievement. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, U.; Madonia, C.; Passanisi, A.; Iacolino, C.; Di Maggio, R. Is sensation seeking linked only to personality traits? The role of quality of attachment in the development of sensation seeking among Italian adolescents: A longitudinal perspective. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buzzai, C.; Passanisi, A.; Aznar, M.A.; Pace, U. The antecedents of teaching styles in multicultural classroom: Teachers’ self-efficacy for inclusive practices and attitudes towards multicultural education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, A.; Katz, I. Self-compassionate teachers are more autonomy supportive and structuring whereas self-derogating teachers are more controlling and chaotic: The mediating role of need satisfaction and burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 96, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, B.; Aelterman, N.; Beyers, W.; Aper, L.; Buysschaert, F.; Vansteenkiste, M. The role of teachers’ motivation and mindsets in predicting a (de) motivating teaching style in higher education: A circumplex approach. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Woolfolk-Hoy, A.; Hoy, W.K. Teacher-efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 1998, 68, 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, P.; Sharma, U.; Dimitrov, D.M.; Di Gennaro, D.C.; Pace, E.M.; Zollo, I.; Sibilio, M. Indagine sulle percezioni del livello di efficacia dei docenti e sui loro atteggiamenti nei confronti dell’inclusione. [Investigation into teachers’ perceptions of the level of effectiveness and their attitudes towards inclusion]. L’integrazione Scolastica E Soc. 2016, 15, 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, G.; Assor, A.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Kaplan, H. Autonomous Motivation for Teaching: How Self-Determined Teaching May Lead to Self-Determined Learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, D.; Danioni, F.; Benevene, P. Teachers’ self-efficacy: The role of personal values and motivations for teaching. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. Declaration of Helsinki. In International Encyclopedia of Ethics; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. SPSS. Statistics for Macintosh, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781462523351. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Jia, F. A new procedure to test mediation with missing data through nonparametric bootstrapping and multiple imputation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2013, 48, 663–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Modeling 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781848728394. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, B.A.; Chacon, M.C.M. Sources of Teacher Self-Efficacy in Teacher Education for Inclusive Practices. Paidéia 2021, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Z.; You, X.; Gao, J. Value congruence and teachers’ work engagement: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 80, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.L.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Amiot, C.E. Self-determination as a moderator of demands and control: Implications for employee strain and engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Kuss, D.J.; Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Dawes, C.; Justice, L.V.; Männikkö, N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Terashima, J.P.; Billieux, J.; et al. Measurement invariance of the short version of the problematic mobile phone use questionnaire (PMPUQ-SV) across eight languages. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, U.; D’Urso, G.; Zappulla, C. Adolescent Effortful Control as Moderator of Father’s Psychological Control in Externalizing Problems: A Longitudinal Study. J. Psychol. 2018, 152, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, U.; Zappulla, C. Problem Behaviors in Adolescence: The Opposite Role Played by Insecure Attachment and Commitment Strength. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.; Loughran, J.; Russell, T. Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 1020–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabarro, R.C.C.; Teixeira, M.C.T.V.; Schmidt, C. Translation and transcultural adaptation of the self- efficacy scale for teachers of students with autism: Autism Self-Efficacy Scale for Teachers (Asset). Rev. Bras. Educ. Espec. 2018, 24, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Dawes, C.; Pontes, H.M.; Justice, L.; Rumpf, H.J.; Bischof, A.; Gässler, A.K.; Suryani, E.; et al. Cross-cultural validation of the compulsive internet use scale in four forms and eight languages. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Santoro, G.; Pace, U.; Passanisi, A.; Schimmenti, A. Problematic Facebook use and anxiety concerning use of social media in mothers and their offspring: An actor–partner interdependence model. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 11, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | DS | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.66 | 0.73 | −1.13 | 3.04 | α = 0.94 | |||||

| 4.35 | 0.68 | −1.49 | 3.13 | 0.42 ** | α = 0.82 | ||||

| 5.68 | 0.93 | −1.39 | 3.73 | 0.38 ** | 0.54 ** | α = 0.91 | |||

| 5.78 | 0.93 | −1.87 | 6.00 | 0.40 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.83 ** | α = 0.92 | ||

| 2.46 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 1.33 | −0.10 * | −0.16 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.12 * | α = 0.88 | |

| 2.04 | 0.80 | 1.80 | 5.95 | −0.15 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.38 ** | 0.59 ** | α = 0.87 |

| β | SE | Lower Bound (BC) 95% CI | Upper Bound (BC) 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Autonomous Motivation | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.54 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Autonomy-Supportive | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.32 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Structuring | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.35 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Controlling | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.15 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Chaotic | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.08 |

| Autonomous Motivation → Autonomy-Supportive | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.91 |

| Autonomous Motivation → Structuring | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.80 |

| Autonomous Motivation → Controlling | −0.22 | 0.08 | −0.43 | −0.09 |

| Autonomous Motivation → Chaotic | −0.25 | 0.07 | −0.34 | −0.08 |

| Indirect effect via Autonomous Motivation | ||||

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Autonomy-Supportive | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Structuring | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.35 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Controlling | −0.10 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.03 |

| Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices → Chaotic | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.03 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Passanisi, A.; Buzzai, C.; Pace, U. Special Education Teachers: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in the Relationship between Teachers’ Efficacy for Inclusive Practice and Teaching Styles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710921

Passanisi A, Buzzai C, Pace U. Special Education Teachers: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in the Relationship between Teachers’ Efficacy for Inclusive Practice and Teaching Styles. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710921

Chicago/Turabian StylePassanisi, Alessia, Caterina Buzzai, and Ugo Pace. 2022. "Special Education Teachers: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in the Relationship between Teachers’ Efficacy for Inclusive Practice and Teaching Styles" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710921

APA StylePassanisi, A., Buzzai, C., & Pace, U. (2022). Special Education Teachers: The Role of Autonomous Motivation in the Relationship between Teachers’ Efficacy for Inclusive Practice and Teaching Styles. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710921