Why Are Some Male Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients High Utilisers of Emergency Health Services? An Asian Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

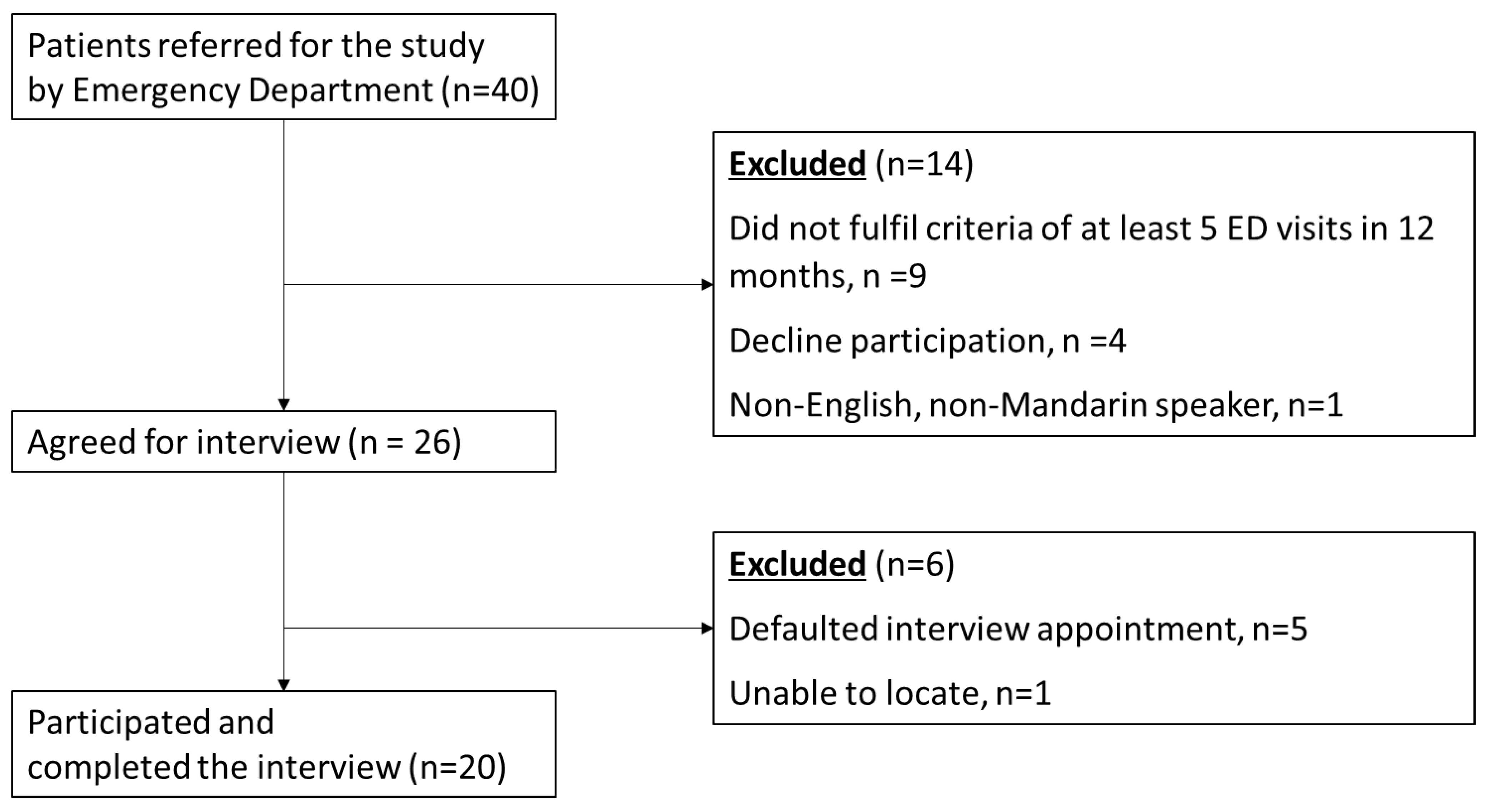

2.3. Recruitment Process

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics

3.2. Reasons for High Utilization of Emergency Health Services

3.2.1. Treatment for Alcohol-Related Health Conditions

I felt dizzy. I started to have alcohol withdrawal seizures. If I withdraw (from alcohol), I go into seizure… sometimes if I don’t drink, I get alcohol fits. I collapse in [sic] the ground. (Participant 020)

It’s only like you can’t move… then they lift your leg (and) you feel pain. Sometimes you really cannot get up. I know I really (cannot), I cannot [move] that’s why I call (the) ambulance. (If) I’m able to at least go (by) myself to (the) hospital, then I don’t have to call right? (Participant 019)

3.2.2. Treatment for Existing Health Conditions Unrelated to Alcohol Use

…Go down to the shop (to) buy things and I don’t know what happened. (Then) I’ll be in the ambulance…I lose [sic] consciousness… I asked the paramedic “what happened? I (had) fits?” She said, “No, no, no. You were just lying unconscious.” And I said “I never drink… yet.” They told me, “…you suffered a mild heart attack.” From my previous epilepsy, this was my…first attack. (Participant 013)

[Regarding calling of ambulance] About two times a month… because of my pain. For me, I got [sic] hernia. Before that (I) had this chest pain, always get this chest pain. I do…go on my own (to the hospital). (But) when the pain is too…can’t bear the pain, there’s no choice, where (do) you want to go? (Participant 017)

3.2.3. Alcohol Intoxication That Led to Intervention by Concerned Bystanders

I collapse in [sic] the ground. People got [sic] call 995… It’s not that I called… There are occasions when (the) public call [sic]. (Participant 020)

Sometimes, I sit (on) the bench, below the (housing) block, (people) say I fainted. When I lie down, somebody call (the) ambulance. Actually, I’m sleeping! (Participant 001)

3.2.4. Preference for High-Quality Service and Care Levels Afforded by Emergency Services and Departments

The ambulance that comes…sometimes it’s the same people. So they know me, know what’s wrong with me…before I explain to them. They spend some time with me, then they see (that) I’m okay. It’s not that we are well-known, they just remember- remember- (me). (Participant 018)

If I come by ambulance, excellent service. Very fast, everything (gets) done. If I come personally by taxi, or (with) my sister or brother, then I [sic] got to wait and wait and wait. But ambulance is a very fast service. (Once) they come (and) they bring you out of the ambulance, they put you on the bed already. (Participant 015)

Actually, I don’t want to call. Because when you call, your number is already there (in the system). Every time (when) the same person (keeps) calling, (the paramedics) don’t even come (anymore], because it is pulling a fast one… (When I go to the A&E because of drinking) I feel a bit guilty because I think these emergency services shouldn’t be used on me. (Participant 003)

Maybe I feel that it’s no good [sic], I feel sorry every time because the more people like me come here too often, it will delay and reduce the chances for other people (to use the emergency services or department). (Participant 011)

Here, accident [sic] people come down, heart problem, kidney problem, sometimes throat problem, a lot of cases. Sometimes some doctors also see me only [sic] (and they went,) “You again!” (Did) they think (that) I (really) want to come to hospital? (Participant 010)

3.3. Motivations for Drinking

3.3.1. To Cope with Personal Issues

(The reason) I drank the 17 bottles (of beer) was because of frustration. (I was) wrongfully dismissed, wrongly accused. And that’s the reason why I get very angry, very irritated, very frustrated, and I just simply drink and drink and (then go to) sleep. (Participant 003)

When the pain (gets unbearable and) I cannot take it [sic], (it) means (that) the medicine never work. I take beer to subside the pain. (I take) about two cans of beer, only 8%. But I never bluff you, alcohol (actually) never works. (Participant 009)

Lonely. You know you’re divorced. (There is) nobody with you, no friends. (I) Want to cut (down drinking)… (but) sometimes you lonely, you feel boring [sic]… you stay alone, (it’s) very difficult! (Participant 010)

You see, I need to escape because of the boredom. So I took [sic] on the drinks. (Participant 001)

3.3.2. To Cope with Symptoms Suggestive of Alcohol Dependence

I tried to give up (drinking) on my own, but because of the withdrawal symptoms, then I just… I chose to go back to drinking rather than to undergo the withdrawal symptoms. (It feels) terrible, I tell you. Vomiting, shaking, your hands will shiver, your legs will tremble, that kind of thing [sic]. (Participant 002)

After a certain period then [sic] you don’t drink, you feel like you’re missing something. (It) feels like withdrawal or what [sic], (although) I’d say it’s not withdrawal. I’d say it’s sort of (the) mind. (Participant 014)

To be at peace, relax, and everything. (Participant 019)

Last time (it) was (to) drink to socialise, to just hang out with the uncles and pass time. The difference is (that) today, I just want to drink and I want to get drunk. I need to get drunk. (Participant 005)

3.3.3. Encouraging Social Environments

But I must also say, it’s not so much of an issue, ‘cause back then (when) I was going to the coffee shop, I’m quite a well-liked person (and) I can have free drinks. (Participant 005)

But I never buy the liquor. My friend is a liquor shop owner so he brought the liquors. (Pariticpant 013)

…Bumped into a friend in my area, he said, “Wah, long time no see.” And I said, “Ya.” So he said, “Come, I buy for you [sic] beer.” (Participant 020)

That time (when) I was trying to go off alcohol for a few months, at a Christmas party my wife saw [sic] (that) I (was) very poor thing [sic], so she asked me to have a can of beer. But I was the first one to pass out. (Participant 003)

…(I was) late half an hour (for work), but they (are) ok. The office (is) very good to me. I never create trouble, drink [sic] also never argue with them, so they (are) all very good to me. (Participant 006)

Father knows I drink. He knows (that when it was) working time I drink. (Although) they know but they never disturb me. (Not even) one day also (did) he say “you don’t come [sic] to this church.” He never say. (Participant 017)

Nobody disturb. I’m staying alone. (Participant 001)

I prefer to drink alone with myself [sic]. I couldn’t resist it I feel uncomfortable at home and I don’t want to go out then bring [sic] into trouble. (Participant 019)

3.3.4. Alcohol Consumption Habits Were Simply Not Considered to Be Problematic

I’m not a drinker, (although) I have drank all types of drinks. But I’m not a big addiction [sic] you know. I’m a drinker, I ever drink Chinese wine (and) everything… All I (have) drank before. But I’m not addiction [sic] until shivering, (that every) early morning must [sic] drink. (Participant 006)

My goal is to cut down drinking, (but I need to) cut down (on) the drugs first. (Cutting down the) drug [sic] is very important. I can’t afford to go for 7 years (in prison) you know, next sentence will be 7 years, I cannot sit (in prison). So my goal is to give up drugs (first). Drink [sic] I can (easily) cut down. (Participant 005)

3.4. Protective Factors against Drinking in Study Participants

Temporary Psychological Respite Conferred by Formal Interventions

NAMS [National Addictions Management Service] (have) already discharged me. WE CARE [a community addiction recovery centre] (also) feels that I’m basically okay. Because at least, I don’t drink and I go there [to the recovery centre]. It really helped… helped me (to) become a more healthy [sic] person and (engage in) positive thinking and (to be) more aggressive (about wanting to change for the better). (Participant 011)

You see, it’s an addiction. After (discharging) from IMH [Institute of Mental Health], after upon discharge (for) about 2 months I stayed away from alcohol. And then subsequently I took on (alcohol again), because boredom sets in, you know. (Participant 002)

At the addiction centre [National Addictions Management Service], you cannot contact (anybody) outside. Visitors also cannot come and see you. But it’s like a Hotel 81 [a brand of budget hotel in Singapore], got pillow got everything [sic], every type of food (that) you want… Chinese food, Indian food, Malay food, everything they’ll give you. But (there is) no contact with the outside world for 2 weeks. It’s a very good thing they did [sic]. After 2 weeks I feel better. Down there, they give (you) such a kind of environment that you won’t feel like drinking also [sic]. You know, got [sic] every kind of games down there… so you forget about drinking. (Participant 009)

I prefer to do it [quit drinking] alone… I think the programmes [formal interventions] are good, but personally I feel more comfortable helping myself rather than engaging external organisations. (Participant 004)

I personally feel that the interventions are helpful but I’m not improving because I cannot accept (that I have to stop drinking) and I cannot stop drinking. I think we addicts, we don’t care for ourselves and so we don’t take professional advice seriously. (Participant 003)

3.5. Deterring Social Environments

My sisters don’t like me to drink. Every time [sic] I get angry with them, they blame it on my drinking. My roommate (also) discourages me, so I usually don’t drink when he is around. My pastor, church people, people at WE CARE [a community addiction recovery centre] and NAMS [National Addictions Management Service] don’t want me to drink. (Participant 003)

If I go out with certain people, I cannot drink [because they do not like drinking] means I don’t drink. Suppose (if) I follow with my church people, I don’t drink, I don’t smoke in front of them. Even (if) I want to smoke, (and) I’m a heavy smoker, (if) they (are) around me means I won’t smoke. (Participant 006)

3.6. Perceived Ability to Meaningfully Contribute to the Society

Small can, 330? So maybe… [drink] seven to eight drinks per day? Why I said five drinks is because some days I go to church, I won’t drink. (Participant 020)

Before (when) I had a job, I had about three (drinks a week). Right now I got no job, (I drink) almost on an everyday daily basis. Because I (have) got no job, (I have) nothing to do at home. So if I am gainfully employed… then Singapore recognises me as a contributor to the society, then I will feel ok. But right now I got nothing to do. So what you want me to do at home? Sit down only (and) watch TV? No, right? (Participant 002)

We can have an interval of three days (without drinking), then we (will) drink again. Normally (if we do drink) it’s on Fridays because Saturday we got no job [do not need to work]. Friday (and) Saturday, can. Sunday don’t (drink), because Monday (we) have to wake up early to go to work. So, cannot. (Participant 015)

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Reasons for ED/EMS Usage

4.3. The Challenge in Managing Behaviour

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackwood, R.; Wolstenholme, A.; Kimergård, A.; Fincham-Campbell, S.; Khadjesari, Z.; Coulton, S.; Byford, S.; Deluca, P.; Jennings, S.; Currell, E.; et al. Assertive outreach treatment versus care as usual for the treatment of high-need, high-cost alcohol related frequent attenders: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myran, D.T.; Hsu, A.T.; Smith, G.; Tanuseputro, P. Rates of emergency department visits attributable to alcohol use in Ontario from 2003 to 2016: A retrospective population-level study. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2019, 191, E804–E810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, K.; Newbury-Birch, D.; Phillipson, A.; Hindmarch, P.; Kaner, E.; Stamp, E.; Vale, L.; Wright, J.; Connolly, J. Prevalence of alcohol related attendance at an inner city emergency department and its impact: A dual prospective and retrospective cohort study. Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 33, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boh, C.; Xin, X.; Yap, S.; Pasupathi, Y.; Li, H.; Finkelstein, E.; Haaland, B.; Ong, M.E. Factors Contributing to Inappropriate Visits of Frequent Attenders and Their Economic Effects at an Emergency Department in Singapore. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, T.; Neale, J.; Day, E.; Drummond, C. Qualitative exploration of why people repeatedly attend emergency departments for alcohol-related reasons. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, J.; Parkman, T.; Day, E.; Drummond, C. Frequent Attenders to Accident and Emergency Departments: A Qualitative Study of Individuals Who Repeatedly Present with Alcohol-Related Health Conditions; Alcohol Change UK: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–6.

- Hulme, J.; Sheikh, H.; Xie, E.; Gatov, E.; Nagamuthu, C.; Kurdyak, P. Mortality among patients with frequent emergency department use for alcohol-related reasons in Ontario: A population-based cohort study. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E1522–E1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, K.; D’Onofrio, G. Emergency department screening and interventions for substance use disorders. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2018, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, F.S.G.; Morgan, T.J.; Epstein, E.E.; McCrady, B.S.; Ms, S.M.C.; Jensen, N.K.; Kelly, S. Engagement and Retention in Outpatient Alcoholism Treatment for Women. Am. J. Addict. 2009, 18, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.E.; Christie, M.M.; Copello, A.; Kellett, S. Barriers and enablers to implementation of family-based work in alcohol services: A qualitative study of alcohol worker perceptions. Drugs: Educ. Prev. Policy 2012, 19, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, T.; Neale, J.; Day, E.; Drummond, C. How Do People Who Frequently Attend Emergency Departments for Alcohol-Related Reasons Use, View, and Experience Specialist Addiction Services? Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunt, K.A.; Weber, E.; Showstack, J.; Colby, D.C.; Callaham, M. Characteristics of Frequent Users of Emergency Departments. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, R.; Wong, M.L.; Hayhurst, C.; Watson, P.; Morrison, C. Designing services for frequent attenders to the emergency department: A characterisation of this population to inform service design. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Deehan, A.; Seed, P.; Jones, R. Characteristics of frequent attenders in an emergency department: Analysis of 1-year attendance data. Emerg. Med. J. 2009, 26, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.H.; Parent, M.C.; Spiker, D.A. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, D.R.; Fook-Chong, S.; Mak, C.C.M.; Tan, X.X.E.; Wu, J.T.; Tan, K.B.; Ong, M.E.H.; Siddiqui, F.J. Nationwide Alcohol-related visits In Singapore’s Emergency departments (NAISE): A retrospective population-level study from 2007 to 2016. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022, 41, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Abdin, E.; Vaingankar, J.; Phua, A.M.Y.; Tee, J.; Chong, S.A. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use disorders in the Singapore Mental Health Survey. Addiction 2012, 107, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.B.; Pedersen, J.; Thygesen, L.C.; Lau, C.J.; Christensen, A.I.; Becker, U.; Tolstrup, J.S. Alcohol consumption and labour market participation: A prospective cohort study of transitions between work, unemployment, sickness absence, and social benefits. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sio, S.; Tittarelli, R.; Di Martino, G.; Buomprisco, G.; Perri, R.; Bruno, G.; Pantano, F.; Mannocchi, G.; Marinelli, E.; Cedrone, F. Alcohol consumption and employment: A cross-sectional study of office workers and unemployed people. PeerJ. 2020, 8, e8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myran, D.; Hsu, A.; Kunkel, E.; Rhodes, E.; Imsirovic, H.; Tanuseputro, P. Socioeconomic and Geographic Disparities in Emergency Department Visits due to Alcohol in Ontario: A Retrospective Population-level Study from 2003 to 2017. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, M.J.; Booth, B.M.; Feldman, Z.L. Perceived Need for Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorders: Results from Two National Surveys. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009, 60, 1618–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, C.; Gilburt, H.; Burns, T.; Copello, A.; Crawford, M.; Day, E.; Deluca, P.; Godfrey, C.; Parrott, S.; Rose, A.; et al. Assertive Community Treatment for People with Alcohol Dependence: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016, 52, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, N.R.; Houghton, N.; Nadeem, H.; Bell, J.; Mcdonald, S.; Glynn, N.; Scarfe, C.; Mackay, B.; Rogers, A.; Walters, M.; et al. Salford alcohol assertive outreach team: A new model for reducing alcohol-related admissions. Front. Gastroenterol. 2013, 4, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | Participants * (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 55.6 (8.85) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 20 (100) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Chinese | 1 (5) |

| Indian | 16 (80) |

| Malay | 2 (10) |

| Sikh | 1 (5) |

| Religion | |

| Agnostic | 3 (15) |

| Buddhism | 1 (5) |

| Christian | 5 (25) |

| Hinduism | 5 (25) |

| Islam | 4 (20) |

| Sikhism | 1 (5) |

| No religion | 1 (5) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 4 (20) |

| Married | 2 (10) |

| Separated | 1 (5) |

| Divorced | 11 (55) |

| Widowed | 1 (5) |

| Not available | 1 (5) |

| Medical History # | |

| Diabetes | 4 (20) |

| Hypertension | 11 (55) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 6 (30) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 7 (35) |

| Any cardiovascular risk factor † | 15 (75) |

| Liver cirrhosis or previous hepatitis | 6 (30) |

| Epilepsy | 6 (30) |

| Psychiatric condition(s) ^ | 12 (60) |

| Substance Use | |

| Alcohol dependence | 20 (100) |

| Onset of drinking between 10–20 years old | 16 (80) |

| Preference to beer | 15 (75) |

| Smoker | 15 (75) |

| Age started smoking | 16.7 (4.03) |

| Number of cigarettes daily | 12.9 (10.28) |

| Utilisation of Emergency Department | |

| Number of Emergency Department visits in the last 12 months | 15.4 (9.03) |

| Number of alcohol-related Emergency Department visits in the last 12 months | 8.6 (6.72) |

| Characteristic | Participants (%) (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Highest Education | |

| Primary school | 7 (35) |

| Institute of Technical Education (Formal vocational training) | 1 (5) |

| O Levels (General Certificate of Secondary Education) * | 6 (30) |

| A Levels (General Certificate of Education Advanced Level) # | 1 (5) |

| Diploma % | 3 (15) |

| Did not answer | 2 (10) |

| Housing | |

| 1–2 room HDB ^ apartment | 12 (60) |

| 3–4 room HDB apartment | 4 (20) |

| Condominium + | 1 (5) |

| Homeless | 1 (5) |

| Not available | 2 (10) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time employment | 2 (10) |

| Part-time employment | 2 (10) |

| Retired | 1 (5) |

| Unemployed | 15 (75) |

| Lives alone | 5 (25) |

| Previous incarceration | 12 (60) |

| Previous suicide attempt | 4 (20) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goh, P.; Md Amir Ali, L.A.B.; Ou Yong, D.; Ong, G.; Quek, J.; Banu, H.; Wu, J.T.; Mak, C.C.M.; Mao, D.R. Why Are Some Male Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients High Utilisers of Emergency Health Services? An Asian Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710795

Goh P, Md Amir Ali LAB, Ou Yong D, Ong G, Quek J, Banu H, Wu JT, Mak CCM, Mao DR. Why Are Some Male Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients High Utilisers of Emergency Health Services? An Asian Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710795

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoh, Pamela, Lina Amirah Binte Md Amir Ali, Donovan Ou Yong, Gabriel Ong, Jane Quek, Halitha Banu, Jun Tian Wu, Charles Chia Meng Mak, and Desmond Renhao Mao. 2022. "Why Are Some Male Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients High Utilisers of Emergency Health Services? An Asian Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710795

APA StyleGoh, P., Md Amir Ali, L. A. B., Ou Yong, D., Ong, G., Quek, J., Banu, H., Wu, J. T., Mak, C. C. M., & Mao, D. R. (2022). Why Are Some Male Alcohol Misuse Disorder Patients High Utilisers of Emergency Health Services? An Asian Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710795