Receiving Notification of Unexpected and Violent Death: A Qualitative Study of Italian Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

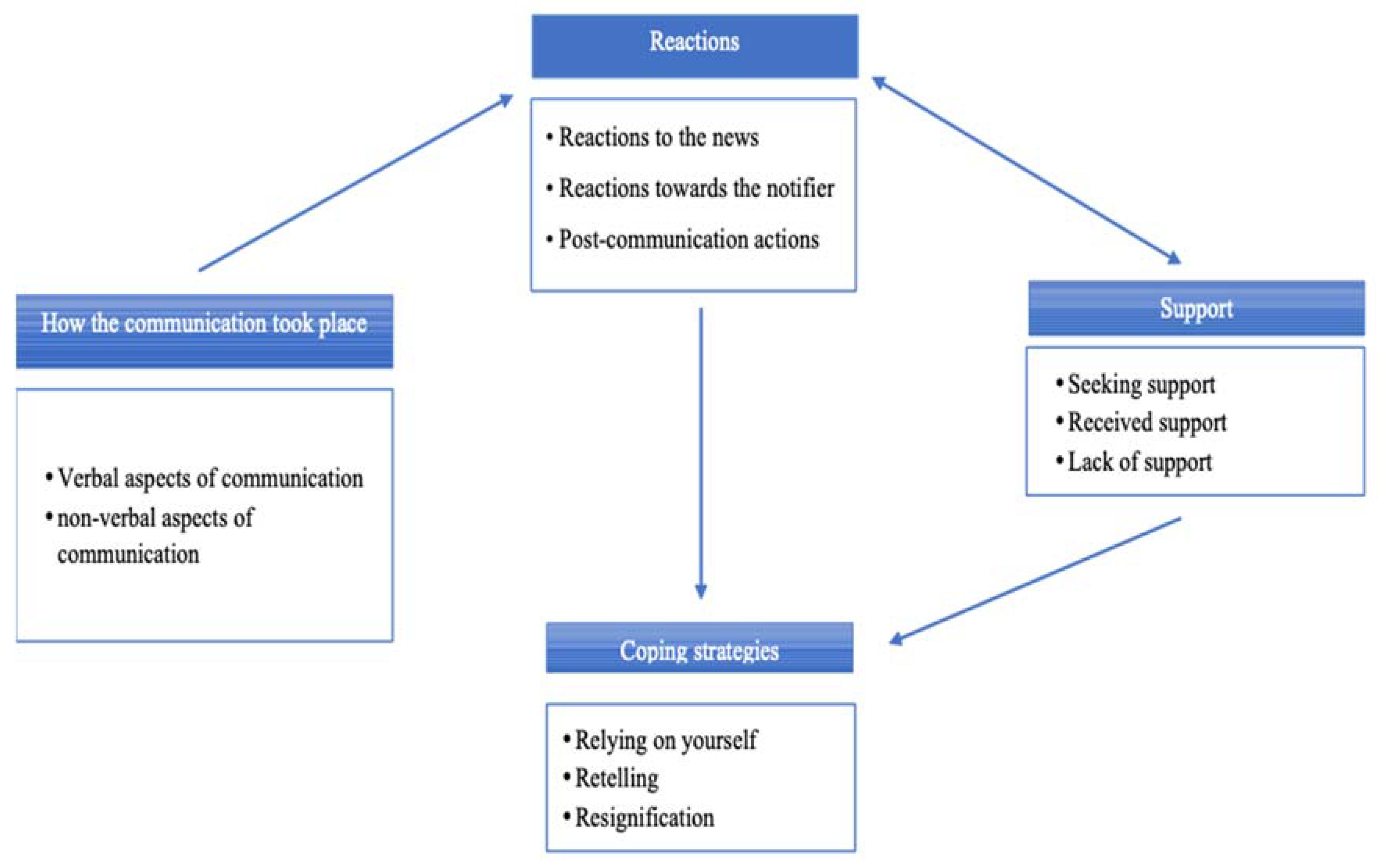

3.1. How the Communication Took Place

“A policewoman rang the doorbell, and just asked me if a boy lived in the house; she was visibly upset. […] I said that at the moment he was not at home but I didn’t know where he was […] The policewoman took the elevator and left […] Then I looked out the window of my son room which was strangely wide open, and I saw a lot of people down the street, and the ambulance. And a body on the ground covered with a green cloth. And I understood […] The policewoman did not allow me to go down to the street, and calmly convinced me to remain at home with her. To my question, ‘Is it my son that I saw? Tell me, is he my son? Is he dead?’, she didn’t say anything but she looked at me in a way that I will never forget for the rest of my life. It was a ‘yes’ that wanted to be a ‘no’, but it was a ‘yes’”(P20, F, 43 years old)

3.2. Reactions (Lived Experience)

3.3. Support

3.4. Coping Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagner, B.; Maercker, A. The Diagnosis of complicated grief as a mental disorder: A critical appraisal. Psychol. Belg. 2010, 50, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fisher, J.E.; Zhou, J.; Zuleta, R.F.; Fullerton, C.S.; Ursano, R.J.; Cozza, S.J. Coping strategies and considering the possibility of death in those bereaved by sudden and violent deaths: Grief severity, depression, and posttraumatic growth. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynearson, E. Retelling Violent Death., 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H.; Finkenauer, C. The traumatization of grief? A conceptual framework for understanding the trauma-bereavement interface. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2001, 38, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Trauma and bereavement: Examining the impact of sudden and violent deaths. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D.; Cimitan, A.; Dyregrov, K.; Tekavčič-Grad, O.; Adriessen, K. Bereavement After Traumatic Death: Helping The Survivors, 1st ed.; Hogrefe Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, H.R.; Pitman, A.; Kozhuharova, P.; Lloyd-Evans, B. A systematic review of studies describing the influence of informal social support on psychological wellbeing in people bereaved by sudden or violent causes of death. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R. Breaking bad news. In Clinical Communication in Medicine, 1st ed.; Brown, J., Noble, L.M., Papageorgiou, A., John, A.K., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Devon, UK, 2015; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- De Leo, D.; Anile, C.; Ziliotto, A. Violent deaths and traumatic bereavement: The importance of appropriate death notification. Humanities 2015, 4, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowski, K.; Dickinson, G.; Weitzman, B.; Roessler, C.; Carter-Snell, C. Sudden unexpected death in the emergency department: Caring for the survivors. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1993, 149, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen, L.; Cadell, S.; Westhues, A. From death notification through the funeral: Bereaved parents’ experiences and their advice to professionals. Omega J. Death Dying 2004, 48, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallowfield, L. Giving sad and bad news. Lancet 1993, 341, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.H.; Frogge, S. Death Notification: Breaking the Bad News with Concern for the Professional and Compassion for the Survivor. 1996. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/death-notification-breaking-bad-news-concern-professional-and (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Stewart, A.E. Complicated bereavement and posttraumatic stress disorder following fatal car crashes: Recommendations for death notification practice. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobgood, C. The educational intervention "GRIEV_ING" improves the death notification skills of residents. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baile, W.F.; Buckman, R.; Lenzi, R.; Glober, G.; Beale, E.A.; Kudelka, A.P. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000, 5, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandeKieft, G. Breaking bad news. Am. Fam. Physician. 2001, 64, 1975–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, R.; Stark, S. The role of forensic death investigators interacting with the survivors of death by homicide and suicide. J. Forensic Nurs. 2015, 11, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iserson, K.V. The gravest words: Sudden-death notifications and emergency care. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2000, 36, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, R.E. Coordinating the death notification process: The roles of the emergency room social worker and physician following a sudden death. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2001, 1, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, R.J. Initial management of bereaved relatives following trauma. Trauma 2011, 14, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T. Sudden traumatic death: Caring for the bereaved. Trauma 2007, 9, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, A.E.; Sabounchi, S.S.; Mirmohammadsadeghi, H.; Rezaei, A. A suitable model for breaking bad news: Review of recommendations. JMED Res. 2014, 2014, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parrish, G.A.; Holdren, K.S.; Skiendzielewski, J.J.; Lumpkin, O. Emergency department experience with sudden death: A survey of survivors. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1987, 16, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkovich, G.J.; Jurkovich, G.J.; Pierce, B.; Pananen, L.; Rivara, F.P. Giving bad news: The family perspective. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2000, 48, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, K.; Cunningham, C.; Murphy, G.; Jackson, D. Helpful and unhelpful responses after suicide: Experiences of bereaved family members. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlevede, E.; Spooren, D.; Henderick, H.; Portzky, G.; Buylaert, W.; Jannes, C.; Calle, P.; Van Staey, M.; De Rock, C.; Smeesters, L.; et al. Perceptions, needs and mourning reactions of bereaved relatives confronted with a sudden unexpected death. Resuscitation 2004, 61, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D.; Zammarrelli, J.; Giannotti, A.V.; Donna, S.; Bertini, S.; Santini, A.; Anile, C. Notification of unexpected, violent and traumatic death: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camic, P.M. Qualitative Research in Psychology: Expanding Perspectives in Methodology and Design, 2nd ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research., 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 34–187. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K.B. Researching internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.; Babbie, E.R. Empowerment Series: Research Methods for Social Work., 7th ed.; Cengage learning: Andover, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 350–380. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.; Maple, M.; Mitchell, A.M.; Cerel, J. Challenges and opportunities for suicide bereavement research. Crisis 2013, 34, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, N.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Pre-Testing in questionnaire design: A review of the literature and suggestions for further research. Mark Res. Soc. J. 1993, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, G. Locus of control and helplessness: Gender differences among bereaved parents. Death Stud. 2004, 28, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroebe, M.; Stroebe, W.; Schut, H. Gender differences in adjustment to bereavement: An empirical and theoretical review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutin-Dias, G.; Dias, R.D.; Scalabrini-Neto, A. Breaking bad news in the emergency department: A comparative analysis among residents, patients and family members’ perceptions. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserson, K.V. Notifying survivors about sudden, unexpected deaths. West. J. Med. 2000, 173, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoenberger, J.M.; Yeghiazarian, S.; Rios, C.; Henderson, S.O. Death notification in the emergency department: Survivors and physicians. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 14, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sep, M.S.C.; van Osch, M.; van Vliet, l.; Smets, E.M.A.; Bensing, J.M. The power of clinicians’ affective communication: How reassurance about non-abandonment can reduce patients’ physiological arousal and increase information recall in bad news consultations. An experimental study using analogue patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 95, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, R.; Rosenzweig, S.; Bernstein, E.; Totten, V. Physician-Patient communication in the emergency department, part 1. Acad. Emerg. Med. 1996, 3, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, S. The interaction between thoughts and emotions following the news of a loved one’s murder. Omega J. Death Dying 2005, 51, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.W., Jr.; DeBernardo, C.R. Death notification: Considerations for law enforcement personnel. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2004, 6, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.D.; Dabney, D.A.; Tapp, S.N.; Ishoy, G.A. Tense relationships between homicide co-victims and detectives in the wake of murder. Deviant. Behav. 2019, 41, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, S.; Entilli, L.; Bettio, F.; Leo, D.D. Live-Chat support for people bereaved by suicide. Crisis 2020, 43, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubin, W.R.; Sarnoff, J.R. Sudden unexpected death: Intervention with the survivors. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1986, 15, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, W.D.; Reay, D.T.; Fligner, C.L. Death notification. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 1990, 11, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.E.; Lord, J.H.; Mercer, D.L. A survey of professionals’ training and experiences in delivering death notifications. Death Stud. 2000, 24, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolletta, S.; Entilli, L.; Filisetti, S. Uncertainty, shock and anger: Recent loss experiences of first-wave COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamino, K.W.S.L.A. Scott and white grief study phase 2: Toward an adaptive model of grief. Death Stud. 2000, 24, 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schut, H.A.; Keijser, J.D.; Bout, J.V.D.; Dijkhuis, J.H. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in the first years of conjugal bereavement. Anxiety Res. 1991, 4, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, E.; Hockey, J. Death, Memory and Material Culture., 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, C.; Sprowl, B. Family members’ experiences with viewing in the wake of sudden death. Omega J. Death Dying 2012, 64, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, J.M. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy, 5th ed.; Springer Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.T. A short guide to giving bad news. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health 2008, 10, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.J.; Litz, B.T. Behavioral interventions for recent trauma. Behav. Modif. 2005, 29, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entilli, L.; De Leo, D.; Aiolli, F.; Polato, M.; Gaggi, O.; Cipolletta, S. Social support and help-seeking among suicide bereaved: A study with Italian survivors. Omega J. Death Dying 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.M.; Breen, L.; Howting, D.A.; Rumbold, B.; McNamara, B.; Hegney, D. Who needs bereavement support? A population based survey of bereavement risk and support need. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T.; Bartone, J.V.; Violanti, J.M.; Gileno, Z.M. Peer support services for bereaved survivors: A systematic review. Omega J. Death Dying 2017, 80, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.; Grebner, K.; Schnabel, A.; Georgi, K. Is the emotional response of survivors dependent on the consequences of the suicide and the support received? Crisis 2011, 32, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neymeier, R. Complicated grief and the reconstruction of meaning: Conceptual and empirical contributions to a cognitive-constructivist model. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 13, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Schut, H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.S.; Folkman, S.; Hansson, R.O.; Schut, H. The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2440–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions related to demographics and the loss 1. Age 2. Gender 3. Nationality 4. Family situation 5. Children 6. Educational title 7. Profession 8. What is your relationship with the lost person? 9. How long ago the loss happened? 10. Under what circumstances did your loved one pass away? Questions about your experience of receiving notification of unexpected and violent death 11. Did you personally receive the news of unexpected and violent death (suicide, homicide, traffic accident, work accident, natural disaster) of a loved one by professional figures? 12. Who communicated the news to you? 13. Where did the communication take place? 14. How was the news communicated to you? (In person, by telephone, by other means…) 15. Did you receive clear and accurate information about what happened? 16. Were there any particularly unpleasant aspects of the communication? If yes, please describe. 17. How do you evaluate the manner in which the communication took place? 18. How did you feel when you received the notification? 19. How did you react toward the person who gave you the news? 20. What struck with you the most about that moment? 21. What did you do after the communication? Was there anything that gave you support? 22. What would you have needed? 23. Would you like to add something? If so, please share your thoughts with us. Thank you! |

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 21–30 | 9 | 17.3% |

| 31–40 | 5 | 9.6% |

| 41–50 | 11 | 21.2% |

| 51–60 | 17 | 32.7% |

| 61–70 | 10 | 19.2% |

| Degree of kinship | ||

| Father/Mother | 19 | 36.5% |

| Son/daughter | 9 | 17.3% |

| Brother/Sister | 12 | 23.1% |

| Husband/Wife | 7 | 13.5% |

| Partner | 1 | 1.9% |

| Daughter-in-law | 2 | 3.8% |

| Friend | 2 | 3.8% |

| Time (in years) since death | ||

| 41–31 | 2 | 3.8% |

| 30–21 | 1 | 1.9% |

| 20–11 | 5 | 9.6% |

| 10–6 | 16 | 30.8% |

| 5–1 | 24 | 46.2% |

| Circumstances of death | ||

| Homicide | 1 | 1.9% |

| Suicide | 28 | 53.8% |

| Road accident | 22 | 42.3% |

| Accident in the mountains | 1 | 1.9% |

| Who made the communication | ||

| Police officer | 14 | 26.9% |

| Carabiniere | 16 | 30.8% |

| Medical doctor | 11 | 21.2% |

| Nurse | 5 | 9.6% |

| Ambulance operator | 2 | 3.8% |

| Doctor and nurse | 4 | 7.7% |

| Lieu where the communication took place | ||

| Law enforcement office | 9 | 17.3% |

| House | 22 | 42.3% |

| Hospital | 14 | 26.9% |

| Train | 1 | 1.9% |

| Car | 1 | 1.9% |

| Ambulance | 1 | 1.9% |

| Road | 4 | 7.7% |

| Medium used for communication | ||

| In person | 34 | 65.4% |

| In person, after anticipatory call | 7 | 13.5% |

| On the phone | 11 | 21.2% |

| Sub-Themes | Codes | Frequencies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme 1. How the communication took place | Verbal aspects of communication | Clarity of presentation | 26 |

| Generic information | 21 | ||

| Non verbal aspects of communication | News intuition | 8 | |

| Notifier empathy | 5 | ||

| Notifier vicinity | 13 | ||

| Attentive and sensitive notifier | 11 | ||

| Coldness of notifier | 14 | ||

| Embarrassed notifier | 8 | ||

| Unattentive and unpleasant notifier | 4 | ||

| Theme 2. Reactions | Reactions to the news | Shock | 16 |

| Sense of emptiness | 10 | ||

| Disbelief | 16 | ||

| Estrangement | 10 | ||

| Emotional Trauma | 5 | ||

| Pain | 35 | ||

| Despear | 15 | ||

| Feeling of dying | 2 | ||

| Death wishes | 4 | ||

| Giving up | 4 | ||

| Lack of the person | 5 | ||

| Body reactions | 6 | ||

| Guilt feelings | 1 | ||

| Stiffening | 5 | ||

| Indescribable emotions | 8 | ||

| Reactions towards the notifier | Anger | 10 | |

| Attempts to deny | 6 | ||

| Identification with the notifier | 2 | ||

| Peacefulness | 4 | ||

| Gratitude | 8 | ||

| Detachment | 7 | ||

| Silence | 4 | ||

| Post-communication actions | Collaboration with notifier | 10 | |

| Body recognition | 14 | ||

| Organ donation | 8 | ||

| Farewell | 12 | ||

| Return to the scene of the accident | 3 | ||

| Return home | 4 | ||

| Funeral organization | 2 | ||

| Communication to friends and relatives | 10 | ||

| Theme 3. Support | Seeking support | Formal support | 13 |

| Informal support | 10 | ||

| Received support | Concret help | 5 | |

| Moral comfort | 18 | ||

| Lack support | Practical | 3 | |

| Emotional | 4 | ||

| Institutional | 2 | ||

| Theme 4. Coping strategies | Relying on yourself | Inner strength | 2 |

| Family responsibility | 4 | ||

| Retelling | Writing | 5 | |

| Partecipation to research on the topic | 3 | ||

| Resignification | Reorganization of everyday life | 5 | |

| Search for explanations | 3 | ||

| Loss as a learning | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Leo, D.; Guarino, A.; Congregalli, B.; Zammarrelli, J.; Valle, A.; Paoloni, S.; Cipolletta, S. Receiving Notification of Unexpected and Violent Death: A Qualitative Study of Italian Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710709

De Leo D, Guarino A, Congregalli B, Zammarrelli J, Valle A, Paoloni S, Cipolletta S. Receiving Notification of Unexpected and Violent Death: A Qualitative Study of Italian Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710709

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Leo, Diego, Annalisa Guarino, Benedetta Congregalli, Josephine Zammarrelli, Anna Valle, Stefano Paoloni, and Sabrina Cipolletta. 2022. "Receiving Notification of Unexpected and Violent Death: A Qualitative Study of Italian Survivors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710709

APA StyleDe Leo, D., Guarino, A., Congregalli, B., Zammarrelli, J., Valle, A., Paoloni, S., & Cipolletta, S. (2022). Receiving Notification of Unexpected and Violent Death: A Qualitative Study of Italian Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710709