Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

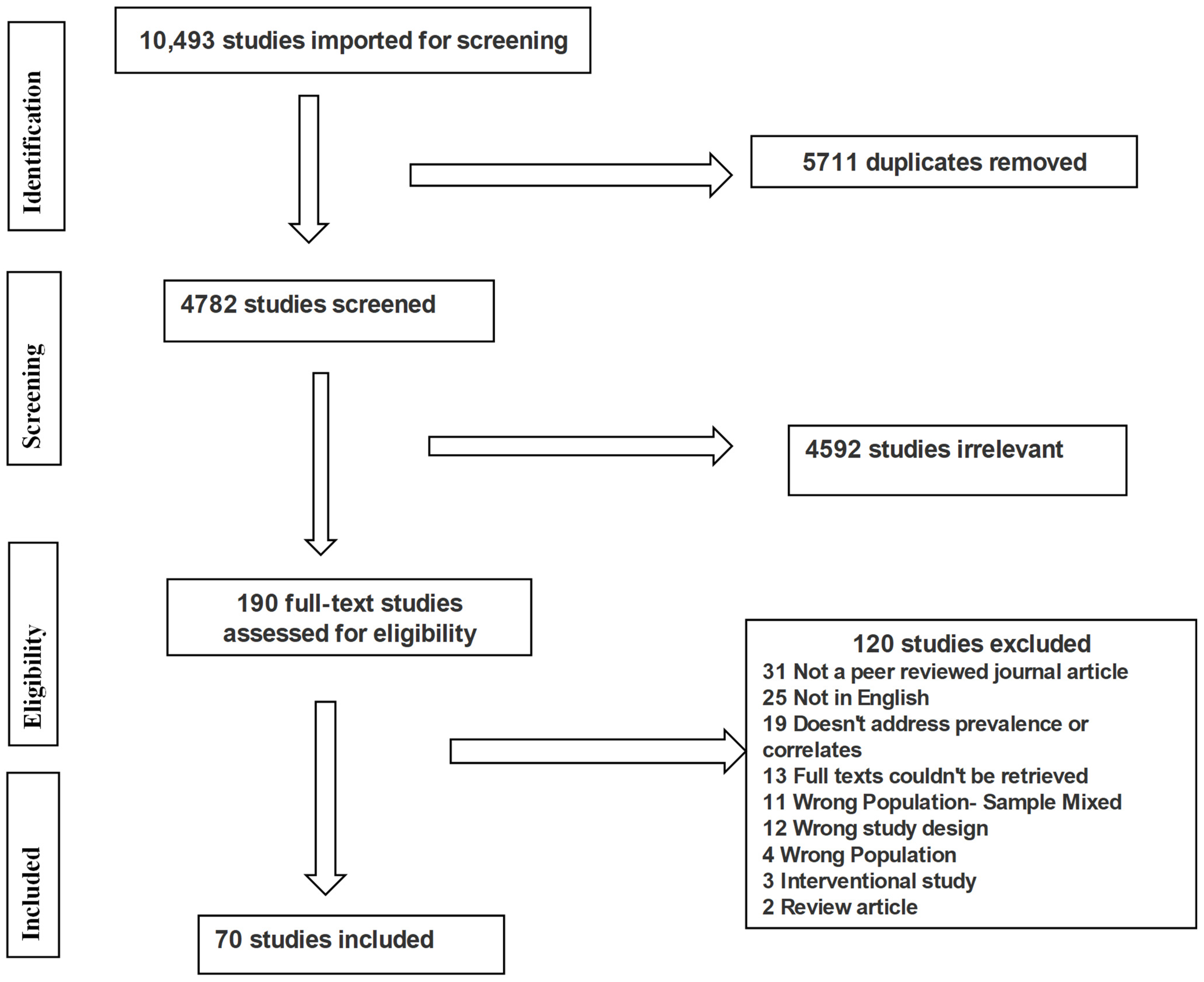

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Developing the Research Question

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Selection of Studies

2.5. Data Charting and Extraction Process

2.6. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

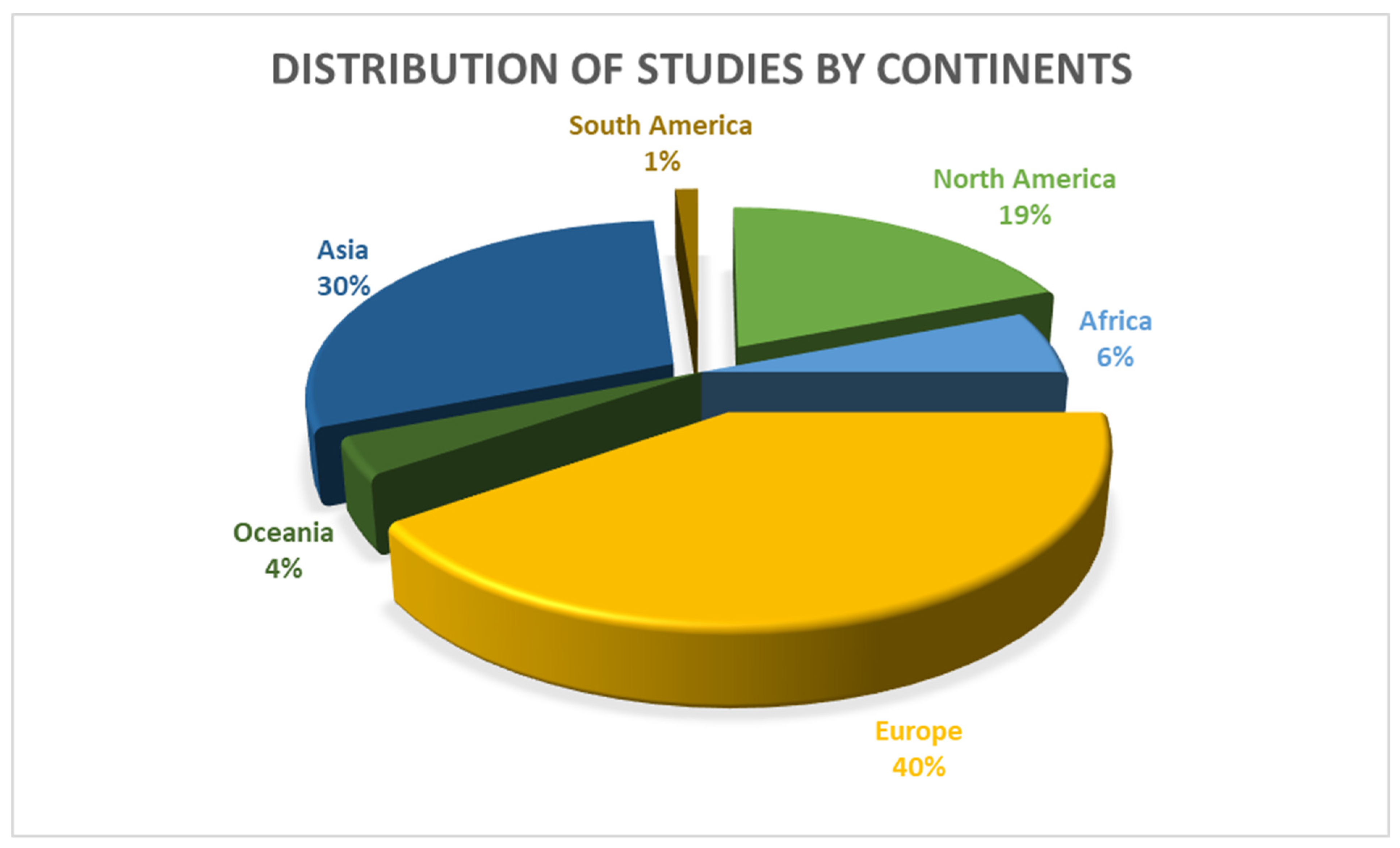

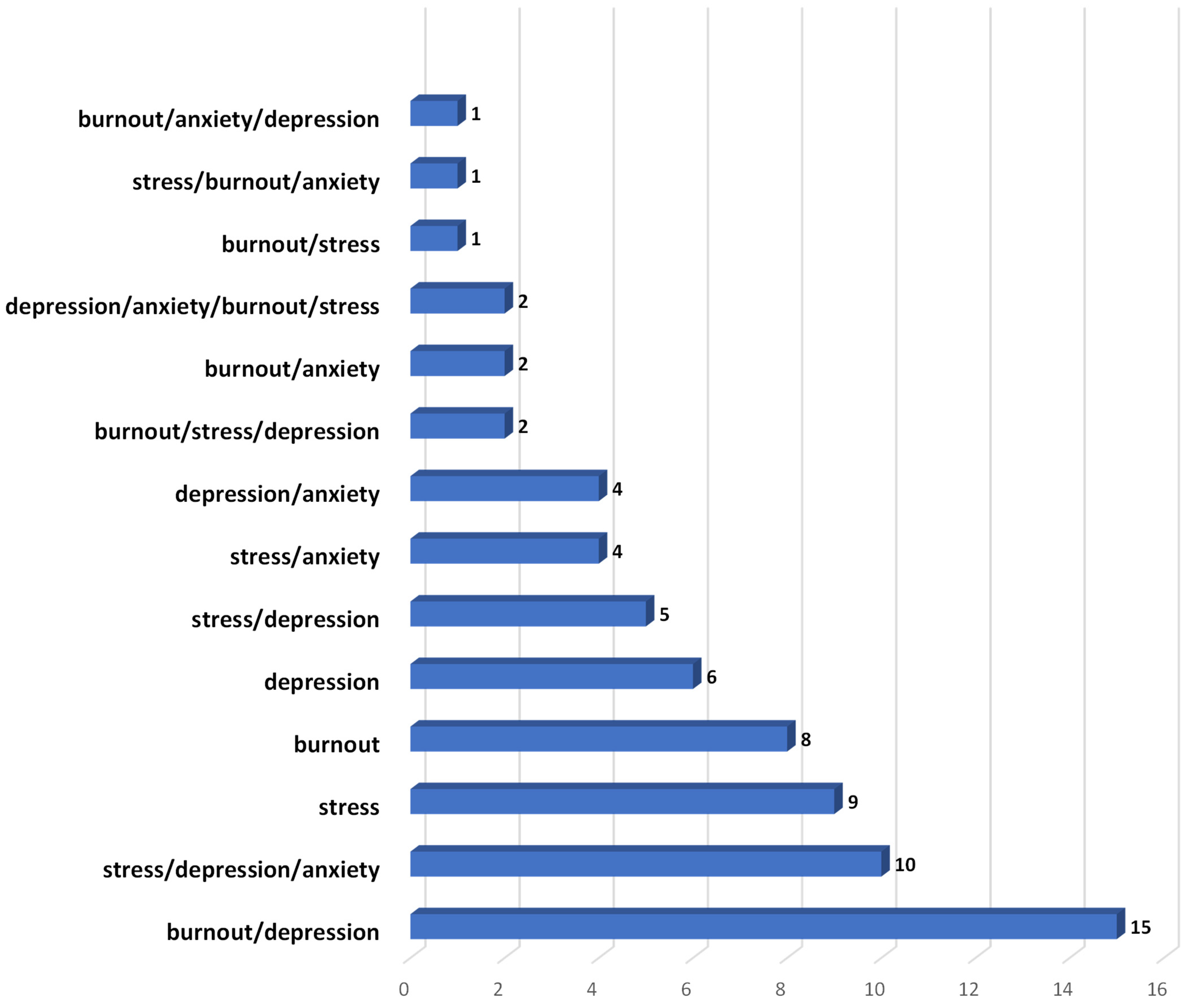

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence and Correlates of Burnout, Stress, Anxiety and Depression

3.3. Prevalence of Stress

3.4. Prevalence of Burnout

3.5. Prevalence of Anxiety

3.6. Prevalence of Depression

3.7. Prevalence Range and Median for Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression Reported in High Quality Studies

3.8. Correlates of Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression

3.9. Association between Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Demographic, School and Work-Related Factors as Determinants of Stress

4.2. Socio-Demographic, Years of Teaching, School and Work-Related Factors as Determinants of Burnout

4.3. Effect of Resilience on Burnout

4.4. Socio-Demographic, School and Work-Related Factors as Determinants of Depression and Anxiety

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors/Year | Country | Study Design | Sample/Population Size (Response Rate %) | Teachers/Age Range | Scales Used | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates of Burnout/Stress | Prevalence of Burnout/Stress | ||||||

| Okwaraji et al., 2015 | [47] Nigeria | Cross-sectional | SS = 432 | Secondary 26–48 years | Maslach burnout inventory, The General health questionnaire (GHQ-12) and the Generic job satisfaction scale | DP: gender, marital status Reduced PA: age, gender, marital status. | 40% emotional exhaustion EE 39.4% for DP 36.8% for reduced PA. |

| Kidger et al., 2016 [81] | UK | Cross-sectional | 555/708/ (78.4%) | Secondary | Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale-WEMWBS) | Stress at work: change in school governance. | Not Mentioned. |

| Bianchi et al., 2015 [99] | France | Survey | SS = 627 | Primary/Secondary | Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) | Burnout symptoms at time 1 (Tl) did not predict depressive symptoms at time 2 (T2). | Time 1 43%, mild burnout 49% moderate burnout, 8% severe burnout. |

| Ramberg et al., 2021 [91] | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Year 2014/16 3948/7147 (55.2%) SS Final = 2732 | Teachers | Stockholm Teacher Survey. The (Questionnaire) | Perceived stress: high job strain, high SOC. Stress: psychological demands at work. High SOC was linked with lower levels of stress and depressed mood. Variation of 4.8% for perceived stress and 2.1% for depressed mood. | Not mentioned. |

| Shukla et al., 2008 [7] | India | Survey | SS = 320 | Secondary | Maslach Burnout Inventory | Lack of PA: subject taught. Science teachers’ higher burnout than arts teachers. More burnout cases in English medium teachers than Hindi medium. Burnout: gender. | EE: 56.56% low burnout, 19.68% average, 23.75% high. DP: 20% high burnout, 16.56% average, and 63.43% low. Lack of PA: 28.43% high burnout. 13.43% average, and 58.12% low. Lack of PA: 28.43% 11.88% high burnout level in all 3 dimensions, 2.81% average burnout on all 3 sub-scales and 40% low burnout level in all dimensions. Burnout of SCIS teachers 26.26%, (AS, 13.76%. EE: 22.5% SCIS and 25% AS teachers’ high burnout category, 21.88% SCIS and 17.5% AS teachers’ average burnout level, 55.62% SCIS and 57.5% AS teachers’ low burnout. Approximately 56–64% in all dimensions of the sample is showing low burnout levels. |

| Pohl et al., 2022 [48] | Hungary | Cross-sectional | 1817/2500 (72.7%) | High school/18–65 | Maslach Burnout Inventory. | Severe burnout, EE and DP: Internet addiction Internet addiction was associated with severe burnout (10.5 vs. 2.7%, p < 0.001), moderate (36.8 vs. 1.7%, p < 0.001), and severe (6.3 vs. 0.1%, p < 0.001). | 26.0% mild, 70.9% moderate, and 3.1% severe burnout. |

| Papastylianou et al., 2009 [3] | Greece | Cross-sectional | 562/985 (57.1%) | Primary/30–45 | Maslach and Jackson, MBI: Maslach Burnout Inventory. | EE: depressed affect, positive affect, degree of role clarity, role conflict and role ambiguity. | EE: 25.09%, PA 14.27% and DP: 8.65%. |

| Hadi et al., 2009 [76] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 565/580 (97.4%) | Female/male Mean age 40.5 | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS 21) and Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ). | Stress: age, duration of work and psychological job demands. | 34.0% stress, 17.4% of teachers experienced mild stress. |

| Ratanasiripong et al., 2021 [40] | Thailand | Cross-sectional | SS = 267 | Primary/secondary 44.4 | The Maslach Burnout Inventory for Educators Survey, Thai version (MBI-ES). | Stress: marital status negative relation with stress., Family economics status, gender, sleep and resilience. Burnout (EE): relationship quality and age. DD: relationship quality and drinking. PA: resilience and number of teaching hours. | 6.0% had severe to extremely severe stress. |

| Szigeti et al., 2017 [50] | Hungary | Cross-sectional | SS = 211 | Primary/secondary 42.8 | Hungarian version of the MBI–ES | General burnout/EE: overcommitment | General burnout 58%, 13% for EE 11% for DP, and 17% for PA. |

| Hodge et al., 1974 [72] | Wales, England | Cross-sectional | 107/145 (75%) | Secondary, 33 mean | Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-60). | EE: difficulty of subject taught and satisfaction, age. 58% of music teachers thought subject was the most difficult subject to teach, 29% of mathematics teachers. | Music teachers have significantly higher EE and DP (high burnt) scores than mathematics teachers. Music teachers. |

| Baka 2015 [73] | Poland | Cross-sectional | 316/400/ (79%) | Primary/secondary 22–60 | The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. | Job burnout: age and job seniority, work hours, job demands. Job burnout decreases along with age and job seniority. Increased work hours were accompanied by job demands, general job burnout, depression and physical symptoms. | Not mentioned. |

| Othman et al., 2019 [131] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | SS = 356 | Secondary <20->/= 50 | Malay Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). | Stress; gender, educational status, teaching experience, marital status. | 32.3% stress symptoms 25.3% were mild to moderate. 7.0% severe to the extremely severe stress. Female stress 32.7%, Indian/other ethnic 50.6%, lowest educational status 46.1%, longest teaching experience (34.6%), lowest income (33.9%), marriage duration 11–20 years (37.3%), 1–3 children (35.5%), |

| Skaalvik et al., 2020 [18] | Norway | Longitudinal | SS = 262 | High school | Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey. | EE: time pressure. Cynicism: low student motivation. Self-perceived accomplishment: autonomy and low student motivation. Burnout: motivation to quit, job satisfaction. | Not mentioned |

| Li et al., 2020 [55] | China | Cross-sectional | 1741/1795 (97%) | Kindergartens/preschool 18–48 | Chinese version Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Perceived Stress Scale-14. | Burnout rate: overweight/obesity, type of school, income satisfaction, depression. Burnout: age, higher perceived stress levels, shorter years of teaching. Perceived stress (p < 0.001, OR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.13–1.18). | Burnout was 53.2%. 53.0% (851/1607) in female subjects and 56.0% (75/134) in male subjects. |

| Gosnell et al., 2021 [57] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 123/400(31%) | Primary/secondary | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 self-care strategy questionnaire was adapted from a self-care scale in the Mental Health Handbook. | Stress: self-care. The association was moderated by age. Among refugee teachers, women were more stressed than men. Stress: negative correlation with age. Younger teachers experienced higher rates of stress than older teachers. | Refugee teachers 8.3% in the severe or extremely severe stress levels clinical ranges. |

| Capone et al., 2020 [59] | Italy | SS = 285 | High school 29–65 | Burnout Inventory- General Survey (MBI). | EE, and DP: flourishing participants languishing teachers. | 22.1% for EE and 9.5% for DP. | |

| Chan et al., 2002 [74] | China | Cross-sectional | SS = 83 | Secondary 22–42 | The shortened 20-item Teacher Stressor Scale (TSS). e 20-item Chinese shortened version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-20). | Stress: psychological distress. Gender, age. Self-efficacy: psychological distress, social support. | Not mentioned. |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [52] | China | Survey | SS = 590 | Primary/secondary 34 ± 8.11 | Chinese Maslach Burnout Inventory. | Reduced PA and intellectual burnout: somatization EE, DP, and intellectual burnout: gender. Burnout: gender, level of mental health. EE, DP: best predictor anxiety. | EE accounted for 92.8% of the burnout cases, DP for 92.9%, reduced PA for 89.9%, and intellectual burnout for 95.0%). Burnout is more severe in female teachers than in male teachers. |

| Vladut, et al., 2011 [69] | Romania | Cross-sectional | SS = 177 | Primary/secondary/High 22–64 | Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale. | Burnout: rural or urban teaching, self-acceptance, classroom management, work-conditions and confidence. | 49.6% above moderate or severe EE 28.7% on DP 54.1% on inefficacy. |

| Liu et al., 2021 [86] | China | Cross-sectional | 449/500 (89.8%) | High 36.70 | Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). | Job burnout: turnover intention; resilience has negative correlation. EE was the most predictive factor for turnover intention with an explanatory variance of 29.2%, followed by DP with an explanatory variance of 1.9% Lest is low PA with 1.5%. | Not mentioned. |

| Fimian et al., 1983 [44] | US | Survey | 365/800(47%) | Special education | Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI) Survey. Sources of Stress (25 items); Emotional and Behavioral Manifestations of Stress (24 items); Physiological Manifestations of Stress (16 items). | Stress: lack of time to spend with individual pupils, teaching. Special needs, or mixed ability students. Increased workload, feeling isolated, and frustrated because of poor administration attitudes and behaviors. | 87.1% moderately-to-very stressful. (45.6%) much-to-very-much stress. 15.9% (58/365) identified as low-stress, (68.4% (250/365) as moderate-stress, and 15.6% (57/365) as high-stress teachers. |

| Katsantonis 2020 [39] | * 15 Countries. | Survey | SS = 51,782 | Primary | Self-efficacy is domain-specific and three scales reflect the self-efficacy. 5 items scale was designed by OECD (2019) to measure factors that cause workload stress. | Workload stress: self-efficacy in instruction, student-behavior, workplace well-being, work satisfaction. Stress: perceived disciplinary climate. School climate negative effect. Increase work satisfaction results in perceived less stress. 16% (organizational constraints as a predictor of depression). | Japanese participants had greater levels of workload stress than Korean participants. Participants from Belgium perceived greater workload stress. |

| Ratanasiripong et al., 2020 [88] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 174/200 (87%) | Primary/secondary 41.65 | Japanese version of depression, Anxiety, and Stress scale (DASS-42). Japanese version of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). | Stress: resiliency and self-esteem. Strength Higher self-esteem and resilience were significantly correlated to less stress. | Not mentioned. |

| Jurado et al., 2005 [82] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 496/602/ (82.7%) | Primary/secondary (women, 45.3 ± 9.8; men, 44.7 ± 9.7). | Spanish version of Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D). | Job stress: negative correlation with job satisfaction, desire to change job and appraisal by others. Teachers wishing to change jobs (25%; significantly higher score on job stress but low on job satisfaction and appraisal by others. | |

| Bianchi et al., 2021 [132] | France Spain Switzerland | Survey | France (N = 4395), Spain (N = 611), and Switzerland (N = 514) | Schoolteachers | Maslach Burnout Inventory for Educators. Job strain was measured with a shortened version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire. | Burnout: neuroticism prediction (28–34%), job strain (10–12%), skill development, security in daily life, and work–non-work conflict (about 15–18%), sex, age, unreasonable work tasks, workhours, job autonomy, sentimental accomplishment, leisure activities, personal life support. | Not mentioned. |

| Bianchi et al., 2014 [60] | France | Analytical | SS = 5575 | School teachers 41 years; | Maslach Burnout Inventory. Depression was measured with the 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). | EE: Strongly associated with depression than with DP and reduced PA. | No-burnout 13% (750) participants. |

| Hammen et al., 1982 [43] | US | Cross-sectional | SS = 75 | Secondary | DASS-21scale. Bruno’s Teacher stress Inventory | Stress: depressive symptomatology, days off work, school-related factors. | 76% moderate or greater stress 20% level of stress was “almost unbearable.” |

| Méndez et al., 2020 [25] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 210/300 (70%) | 30 to 65 | Maslach burnout inventory. | Burnout: correlates with EE, PA and DP resulting in three burnout profiles (high burnout); (moderate burnout) and (low burnout). Burnout: depressive symptomatology. The higher the burnout the greater the depressive symptomatology | 33.3% high burnout 39.1% low burnout and 27.6% moderate burnout. |

| Jepson et al., 2006 [85] | UK | Cross-sectional | 95/159 (60%) | Primary/secondary | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). 10 scale item, occupational commitment 6 scale item. | Work-related stress, strongest predictor and negative relationship, was occupational commitment, achievement striving experience, level taught. Educational level taught. Occupational commitment increases, perceived stress decreases. | Significantly higher levels of perceived stress were reported from primary school teachers than secondary school. Higher achievement striving experience have higher levels of perceived stress. |

| Al-Gelban 2008 [96] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 195/189 (96.9%) | Male 28–57 | Depression, Anxiety and stress DASS-42 scale. | Depression, anxiety and stress were strongly positively and significantly correlated. | 31% had stress. |

| Lee et al., 2020 [120] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | SS = 150 | Secondary/primary | DASS-21 inventory. | Stress: number of years working. Majority of teachers with stress: either severe and extremely severe level are those working for 11 to 15 years. | 10.7% stress. |

| Bounds et al., 2018 [111] | US | Survey | 108/117 (92%) | Primary/secondary 42 | Teacher Stress Inventory (TSI). | Stress: violence against, urban, suburban, and rural setting. | Urban teachers had the highest levels of stress from violence rather than suburban teachers. |

| Pressley et al., 2021 [56] | US | Survey | SS = 329 | Elementary | The COVID Anxiety Scale. A teacher burnout subscale of stress. | Stress: anxiety factors in pandemic situations. | Not mentioned. |

| Yaman 2015 [93] | Turkey | Survey | SS = 436 | Elementary/branch 35.2 | Mobbing Scale and the Stress subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. Turkish version of the Stress Subscale of DASS. | Stress: predicted positively by humiliation, discrimination, communication barriers, and mobbing scores. | Increment in mobbing will increase stress. |

| Cook et al., 2019 [83] | US | Cross-sectional | 180/105/58.5% | Middle 22 ± 37 | Teacher Stress Inventory. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale. | Stress: teacher spirituality. As teachers’ spirituality increases, their time-management stress and their work-related stress increase. | Not mentioned. |

| Okebukolal 1992 [75] | Nigeria | Survey | SS = 368 | Science | The Occupational Stress Inventory for Science Teachers (OSIST). | Stress: school villages (personnel relation dimension) curriculum, facilities, student characteristics, administrative, and professional growth and self-satisfaction, subject taught, science budget. Science teachers in the rural schools mean stress score of 47.25 (SD = 4.89), urban schools mean stress score of 51.29 (SD = 6.95). | Urban teachers were found to be more stressed than those in rural areas. Female science teachers were more stressed than their male counterparts. |

| Klassen 2010 [77] | Canada | Survey | 951/- (Approximately 75%) | Elementary/secondary | Teacher Stress Inventory. Collective Teacher Efficacy Belief Scale (CTEBS Job satisfaction was measured with a one-factor, three-item, 9-point Likert-type scale. | Stress: collective efficacy, student behavior, gender, workload, class size. | 21.3% females rated the stress from workload “quite a bit” or “a great deal” of stress from workload factors. 13.4% of male teachers rated stress from workload at a mean of 7 or higher. More women (18.6%) than men (12.8%) reported feeling “quite a bit” or “a great deal” of stress from student behavior. |

| Proctor et al., 1992 [45] | UK | Survey | 256 (93%) | Primary 39.68 | Zigmond and Snaith’s 6 Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) Scale and Moos and Insel’s7 Work Environment Scale (WES). | Stress: anxiety, work overload, time pressures, stressors relating to pupils and parents. | 67% found teaching ‘considerably’ or ‘extremely’ stressful, 79 (32%) ‘slightly’ stressful and 2 (1%) ‘not at all’ stressful. |

| Akin 2019 [63] | Turkey | Mixed research method | 460/3478 (13%) | Teachers | Turkish version of the Maslach and Jackson inventory. | DP: marital status. Reduced PA: number of children. | Not mentioned. |

| Chan 1998 [125] | Hong Kong | Cross-sectional | SS = 415 | Secondary 21–61 | Teacher stressor scale and the General Health Questionnaire. | Stress: high support—less anxiety symptoms, psychological symptoms. | 37.3% psychiatry morbidity. |

| Adeniyi et al., 2010 [78] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | SS = 50 | Special Needs | Job Stress Inventory. | Stress: marital status, teaching special needs, lack of pupils’ progress in class work/academic achievement, societal attitudes/respect heavy workload and lack of help/assistance, degree and nature of disabilities of the special need children. | Not mentioned. |

| Beer et al., 1992 [53] | US | Cross-sectional | 86/92(93%) | Grade and high school | Beck’s Depression Scale, the Coopersmith Self-esteem Inventory—Adult Form, Stress Profile for Teachers, and the Staff Burnout Scale. | Burnout and stress: gender, level taught-high/grade school. Grade school teachers experienced more burnout than high school teachers. | Burnout scores higher for female high school teachers than for both male and female grade school teachers. Scores on stress were higher for male high school teachers than for both female high school teachers and male grade school teachers. |

| Liu et al., 2021 [98] | China | Cross-sectional | 907/1004 (90.3%) | Primary and secondary 20 ≥ 50 | Generic Scale of Phubbing, the Maslach Burnout Inventory—General Survey, Ruminative Response Scale, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. | Job burnout: phubbing significant positive effect on job burnout, depression. The relation between job burnout and depression were moderated by rumination. | Not mentioned. |

| Shin et al., 2013 [95] | Korea | Survey | SS = 499 | Middle and high school | Maslach Burnout Inventory–Educator Survey Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. | Burnout: depression; baseline status of depression. Teacher’s burnout leads to subsequent depression symptoms, not vice versa. | Not mentioned. |

| Genoud et al., 2021 [41] | Switzerland | Cross- sectional | SS = 470 | Secondary 24–63 | Maslach’s burnout scale version validated by Dion and Tessier twenty-seven items French; Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). | Burnout: negative affectivity (tendency to feel depression, anxiety, or stress), personal fulfillment. Greater tendency to feel depressed result in teachers experiencing a lower level of personal accomplishment. | Two-thirds of the sample (N = 308) 66% of teachers below average for the three dimensions (stress, depression, and anxiety). |

| Steinhardt et al., 2011 [68] | US | Cross-sectional | /267 (26%) | High/Elementary/middle Mean 45 | Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey (MBI-ES) Modified version of the Teacher Stress Inventory. | Burnout: gender, experienced. Stress: depressive symptoms. Females reported greater chronic work stress and emotional exhaustion. Total effect of stress on depressive symptoms, taking together the direct and indirect effects via burnout, accounted for 43% of the total variance. | Increased stress leads to increased burned out. |

| Pressley 2021 [58] | US | Survey | SS = 359 | Primary/secondary | Teacher burnout scales. | Burnout-stress: COVID-19 anxiety, current teaching anxiety, anxiety communicating with parents, and administrative support. | High level of average teacher burnout stress score of 24.85. |

| Schonfeld et al., 2016 [64] | US | Survey | SS + 1386 | School teachers mean = 43 | The Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure, Depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire. | Burnout and depressive symptoms were strongly correlated. Burnout and depressive symptoms: stressful life events, job adversity, and workplace support. Burnout: anxiety. 86% of the teachers identified as burned out met criteria for a provisional diagnosis of depression. Fewer than 1% in the no-burnout group. | Not mentioned |

| Bianchi et al., 2016 [92] | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | SS = 184 | School teachers Mean 43 | Shirom–Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM) Depression was assessed with the PHQ-9. | Burnout: strongly correlation. Depressive symptoms, moderately correlated with dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative responses, and pessimistic attributions. | Depression “low burnout-depression”, (n = 56; 30%), “Medium burnout-depression” (n = 82; 45%), “High burnout-depression” (n = 46; 25%). (About 8%) reported burnout symptoms at high frequencies and were identified as clinically depressed. |

| Desouky and Allam 2017 [28] | Egypt | Cross-sectional | SS = 568 | High 39.4 ± 8.7 | Arabic version of the Occupational Stress Index (OSI), the Arabic validated versions of Taylor manifest anxiety scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. | OS: Anxiety and depression scores, age, gender, higher qualifications and higher workload. OS, anxiety and depression scores were significantly higher among teachers with an age more than 40 years, female teachers, primary school teachers, higher teaching experience. | OS, anxiety and depression, respectively. 100%, 67.5% and 23.2%, Private schools show a significantly higher prevalence of moderate and severe OS compared to governmental schools (31.6% and 68.4% vs. 22.4% and 67.1%). |

| Jones-Rincon et al., 2019 [65] | US | Cross-sectional | 3003/3361(89%) | Elementary, middle/junior high or high | Patient Health Questionnaire. Job satisfaction was measured with 10 items. | Perceived stress levels: anxiety disorder. Teachers with anxiety disorder reported having higher perceived stress levels. | Not mentioned. |

| Kinnunen et al., 1994 [51] | Finland | Survey | 1012/1308/ (77%) | High/vocational/special/Physical/secondary 45–59 | Maslach and Jackson’s inventory. | EE: gender. Poor work ability. Women exhibit higher scores for EE. | Not Mentioned |

| Martínez et al., 2020 [46] | Spain | Random Sampling | 215/300 (71.7%) | Primary 30 to 65 years M = 44.89 | The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Coping with Stress Questionnaire. | Burnout: depressive symptomatology, and quality of interpersonal relationships. | 48.37% low levels of EE, 25.12% high levels of PA, (b) high levels of EE and DP, and (c) 26.51% low levels of DE and PA. |

| Capone et al., 2019 [70] | Italy | Cross-sectional | SS = 609 | High school, middle school, elementary and primary school. 27 to 65, mean = 48.35 | The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Italian version. The Italian version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Scale. The Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale. | Burnout: collective efficacy, school climate, and organizational justice and relationship. EE and cynicism functioned as significant mediators between the three predictors (opportunities, organizational relationships, and organizational justice) and depression. | Not mentioned. |

| Aydogan 2009 [84] | Turkey N = 83 Germany N = 78 Cyprus N = 74 | Cross-sectional | 255/306 (83%) | High M = 38 ± 6.96, 37.9 ± 6.74, 45.8 ± 10.42 | Shirom–Melamed Burnout Measure. Turkish version of Minnesota Job satisfaction scale. | Burnout: country working, job satisfaction, depression. Cyprus teachers 57% of the variance in burnout explained by depression. 58% of the variance in burnout explained by job satisfaction and anxiety. Germany 575% variance in burnout explained by job satisfaction. | Not mentioned. |

| Belcastro et al., 1983 [49] | US | Cross-sectional | 428/359 (84%) | Public | The Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Teacher Somatic Complaints and Illness Inventory. | burned-out: somatic complaints | More than 11% burned out. 246 (68.5%) not burned-out. |

| Capel 1992 [89] | UK | Cross-sectional | 640/405/63.3% | Middle, upper, high school | The Maslach Burnout Inventory. The Taylor Manifest. | Stress and burnout: role conflict, and role ambiguity, High anxiety. Highest stress level: high workload demands after-school time, lack of recognition for extra work, too much paperwork. Students’ behavior. Burnout: anxiety. | Not mentioned. |

| Ptacek et al., 2019 [54] | Czech Republic | Cross-sectional | SS = 2394 | Primary 18–72 | Questionnaire survey: anamnestic part and Standardized questionnaires: SVF 78, SMBM, ENRICHD SSI, BDI II, USE. | Burnout: length of teaching/employment, healthy lifestyle. Cognitive burnout: age and length of teaching employment. Those with healthy lifestyle (work–life balance) have significantly lower burnout rates. Males–higher emotional burnout, females–higher physical burnout rates). | 18.3% of participants felt definitely threatened by burnout syndrome, 34.9% may be, 9.9% definitely not threatened by burnout syndrome. Long-term stress 21.8%, compared to the (7.5%) do not experience long-term stress. |

| Authors/Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size/Population Size (Response Rate) | Teachers/Age Range | Scales Used | Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates of Depression/Anxiety | Prevalence of Depression/Anxiety | ||||||

| Jurado et al., 2005 [82] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 498/602/ (82.7%) | Primary/secondary (women, 45.3 ± 9.8; men, 44.7 ± 9.7). | Spanish version of Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D). | Depressive symptoms: female gender, age, low job satisfaction, high job stress, desire to change jobs, working at a public school, personality dimensions of harm avoidance (high), novelty seeking (high) and verbal insults from pupils. | Depressive symptoms 35.3% of the teachers. |

| Al-Gelban 2008 [96] | Saudi Arabia. | Cross-sectional | 189/195 (96.9) | Male 28–57 | Depression, Anxiety and stress DASS-42 scale. | Depression, anxiety, and stress were strongly, positively, and significantly correlated. | 25% percent had depression 43% had anxiety. |

| Fimian et al., 1983 [44] | US | Survey | 365/800 (47%) | Special education | Emotional and Behavioral Manifestations of Stress (24 items); and Physiological Manifestations of Stress (16 items). | Depressed/anxious: teaching special needs. | Not mentioned. |

| Lee et al., 2020 [120] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | SS = 150 | Female primary/secondary | DASS-21 inventory. | Depression: gender, years of work. Female teachers who suffered depression are those who have been working about 11–15 years. | 15.3% depression; 30.7% anxiety. |

| Ratanasiripong et al., 2020 [88] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 174/200 (87%) | Primary/secondary 41.65 | Japanese version of depression, Anxiety, and Stress scale (DASS-42. Japanese version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). | Depression and anxiety: resiliency and self-esteem, grade taught. Strength significantly predicted anxiety. | Anxiety in secondary school teachers significantly lower than elementary school teachers. |

| Schonfeld 1992 [90] | New York, US | Longitudinal | SS = 255 | Women 27 | Center for Epidemiologic Studies– Depression Scale (CES-D). | Depressive symptoms: work-environment, job satisfaction. Whites but not among principally Black and Hispanic subsample, motivation has negative affectivity. | Not mentioned. |

| Vladut, et al., 2011 [69] | Romania | Cross-sectional | SS = 177 | Primary/secondary/high | The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale. | Anxiety/depression: burnout dimensions, demographic variables, mismatches between work-conditions gender, perception of reward and community. | Higher levels of emotional exhaustion. EE or DP and PA had significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. |

| Bianchi et al., 2014 [60] | France | Analytical | SS = 5575 | Teacher, mean 41 | Depression was measured with the 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). | Depression: burnout: | 90% of the teachers identified as burned out met diagnostic criteria for depression, mainly major depression (85%). 3% (n = 19) of the no-burnout group were identified as depressed, mainly minor depression or depression not otherwise specified (2%). |

| Hammen et al., 1982 [10] | US | Cross-sectional | SS = 75 | Secondary | The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale. | Depressive symptomatology: stress, stress-related, cognitions regarding the consequences of the stressful circumstances, days off work. | 8% reported major depression. 12% teachers met criteria for possible minor depression. 20% debilitating array of symptoms approximating a clinically significant depression syndrome. |

| Baka 2015 [73] | Poland | Survey | 316/400 (79%) | Elementary/secondary 22–60 | Depression (the Beck Hopelessness Scale). | Depression: 16% high organizational constraints predict depression. Interpersonal conflict, organizational constraints and 2% workload predicts depression. | Not mentioned. |

| Lee et al., 2020 [120] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | SS = 150 | female primary/secondary | DASS-21 inventory. | Depression: gender, years of work. Female teachers who suffered depression are those who have been working about 11 -15 years. | 15.3% depression; 30.7% anxiety. |

| Pressley et al., 2021 [56] | US | Survey | SS = 329 | Elementary | The COVID Anxiety Scale. A teacher burnout subscale of stress. | Anxiety: stress and communication within the school, and with parents, providing instruction in a virtual environment. Anxiety: COVID-19 pandemic. online teaching was positively related to anxiety in communications. | 56.2% no change in anxiety. 38.9% of participants reported reduced anxiety, 4.9% of teachers felt more anxiety than their baseline at the 1st week of school. Almost 40% had a decrease in anxiety during the 1st month of the 2020–2021 school year. |

| Besse et al., 2015 [31] | US | Survey single-stage sample cluster | 3003/3361 (89%) | Elementary, middle, or high school, mean = 43.9 years | Occupational health survey and Patient Health Questionnaire. | MDD: Hispanic, divorced, years of experience, taught at elementary level, low job satisfaction and higher absenteeism and increased likelihood of leaving the profession, perceived stress, anxiety. | Teachers with MDD had higher levels of perceived stress, anxiety. |

| Peele et al., 2020 [121] | Ghana | Randomized control trial | SS = 444 | Kindergarten | Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire. | Anxiety and depressive symptoms: poor workplace environment, social support, lack of parental support was associated with more anxiety (b = 0.12, p = 0.002), new to the local community. Depressive symptom: household food insecurity. | Poor workplace environment led to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms. |

| Beer and Beer 1992 [53] | US | Survey | 86/92 (93) | Grade and high school | Beck’s Depression Scale, the Coopersmith Self-esteem Inventory—Adult Form, Stress Profile for Teachers, and the Staff Burnout Scale. | Depression: self-esteem, negative association. Teachers in an institutional setting, there is no significant difference for teaching level or sex on depression. | Not mentioned. |

| Proctor et al., 1992 [45] | UK | Survey | 256 (93%) | Primary 39.68 | Zigmond and Snaith’s 6 Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) Scale and Moos and Insel’s7 Work Environment Scale (WES). | Anxiety/depression: stressors intrinsic to teaching and related to organizational factors within schools, ensuring pupil progress, work overload, time pressures, role conflict. | 79% low or normal level of depression. 44 (17%) borderline scores and 10 (4%) clinical depression. Anxiety: 92 (36%) had normal scores and 67 (26%) borderline, 97 (38%) scored at a clinical level. |

| Liu et al., 2021 [98] | China. | Survey convenient sampling method | 907/1004 (90.3%) | Primary and secondary 20 ± 50 | Generic Scale of Phubbing, Ruminative Response Scale, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. | Depression: phubbing. Combination of phubbing and rumination had no significant effect on depression. | Not mentioned. |

| Shin et al., 2013 [95] | Korea | Survey | SS = 499 | Middle and high school | Maslach Burnout Inventory–Educator Survey Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. | Depression: burnout. Positive relationship between baseline status of teacher burnout and depression. | Not mentioned. |

| Genoud and Waroux 2021 [41] | Switzerland | Cross-sectional | SS = 470 | Secondary 24–63 | French: Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). | Anxious profile: emotional exhaustion. Depressive profile: sense of personal accomplishment, no negative affective trait. | 66% (two-thirds) (N = 308) below average for the three dimensions (depression, anxiety, and stress). |

| Pohl et al., 2022 [48] | Hungary | Cross-sectional | 1817//2500 (72.7%) | High 18–65 | Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-SF). Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire. | Depression: internet addiction. | No depression 37.1% (673/1817), 58.9% (1070/1817) had mild, 3.5% (65/1817) had moderate and 0.6% (9/1817) had severe depression. |

| Steinhardt et al., 2011 [68] | US | Cross-sectional | /267 (26%) | High/elementary/middle, mean 45 | The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | Depressive symptoms: EE. Positive relationships with DP and reduced PA. Chronic work stress, experienced. | High school teachers reported greater depressive symptoms. |

| Pressley 2021 [58] | US | Survey | 359 | Primary/secondary | COVID Anxiety Scale. | Anxiety: stress, COVID-19, communicating with parents, administrative support, providing instruction in a virtual environment. Anxiety about online teaching was positively related to anxiety in communications. | Virtual instruction teachers have the most increase in anxiety. |

| Ratanasiripong et al., 2020 [88] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 174/200 (87%) | Primary/secondary 41.65 | Japanese version of depression, Anxiety, and Stress scale (DASS-42). Japanese version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). | Resilience and self-esteem significantly predicted depression and anxiety. | Not mentioned. |

| Ptacek et al., 2019 [54] | Czech Republic | Survey | SS = 2394 | Primary 18–72 | Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II). | Depression: burnout. There is a strong and significant correlation between burnout and depressive symptomatology. | 15.2% mild to severe depression. |

| Bianchi et al., 2016 [92] | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | SS = 184 | School teacher, mean 43 | Depression was assessed with the PHQ-9. | Depressive symptoms: burnout, dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative responses, and pessimistic attributions. | Depression” low burnout-depression,” (n = 56; 30%), “medium burnout-depression” (n = 82; 45%), and “high burnout-depression” (n = 46; 25%). 14/184 (about 8%) reported. |

| Mahan et al., 2010 [71] | US | Cross-sectional | 168/756 (23.9%) | High, mean 42.6 | Ongoing Stressor Scale (OSS) and the Episodic Stressor Scale (ESS), the Co-worker and Supervisor Contents of Communication Scales (COCS), the State Anxiety inventory (S-Anxiety), and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | Anxiety and depression: ongoing and episodic stressors and support, 28% (adjusted 25%) of the variability in anxiety and 27% (adjusted 24%) of the variability in depression. Co-worker support had an inverse relationship to anxiety and depression, work environment stressor. | Higher levels of ongoing stressors, leads to higher levels of anxiety and depression, higher levels of co-worker support related to lower levels of anxiety and depression. |

| Desouky et al., 2017 [28] | Egypt | Cros-sectional | SS = 568 | High | Arabic version of the Occupational Stress Index (OSI), the Arabic validated versions of Taylor manifest anxiety scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. | Anxiety and depression: occupational stress, OS), age, female teachers, primary school teachers, higher teaching experience, higher qualifications and higher workload. | OS anxiety and depression (100%, 67.5% and 23.2%), respectively. Mild, moderate and severe depressive symptoms among teachers was (19.7%, 2.8% and 0.7%), respectively, and little, mild, severe and very severe anxiety was (17.6%, 23.2%, 7.0% and 19.7%), respectively. |

| Jones-Rincon et al., 2019 [65] | US | Cross-sectional | 3003/3361 (89.3%) | Elementary, middle/junior high or high | Patient Health Questionnaire. Job satisfaction was measured with 10 items. | Anxiety disorder: absenteeism, MDD, panic disorder, and somatization disorder and higher intent to quit, Hispanic, subject taught, job satisfaction and job control, years taught. teaching (p = 0.009). | 65.8% major depression in the anxiety group and 11.2% major depression in the no anxiety group. Other depressive disorder among anxiety disorder group 8.4% and no-anxiety group 7.2%. |

| Borrelli et al., 2014 [133] | Italy | Cross-sectional | 113/180 (63%) | Primary/middle | The Karasek Job Content Questionnaire, the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | Depression and anxiety: Job demand and low social support. | About 50% scored above the threshold for depression and for anxiety on self-rating questionnaires. |

| Kinnunen et al., 1994 [51] | Finland | Survey | 1012/1308/ (77%) | High/vocational/special/physical/secondary 45–59 | Anxiety-contentment and depression-enthusiasm; six-item, six-point scales. | Job-related anxiety and depression: subject taught, age, job competence, and job aspiration, lack of PA. Physical education teachers, sex, poor work ability. | Not mentioned. |

| Martínez et al., 2020 [46] | Spain | Random Sampling | 215/300 (71.7%) | Primary 30 to 65 years, M = 44.89 | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Coping with Stress Questionnaire. | Depressive symptomatology: quality of interpersonal relationships at school, dimensions of burnout. | Not mentioned. |

| Hadi et al., 2008 [94] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 565/580 (97.4%) | Secondary M = 40.5 | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS 21) and Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ). | Depression: decision latitude, psychological job demand and job insecurity. | The prevalence of depression was 49.1% (45.0, 53.2). Mild level of depression (21.0%). |

| Ali et al., 2021 [66] | Fiji. | Cross-sectional | SS = 375 | Physical education 20 to 55 years | The Stress with COVID-19 Scale (SCS). The Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS). | Anxiety: social support, and sexual satisfaction during the COVID-19 lockdown, marital status. Married physical education teachers experience more stress. | Married couples scored higher on stress. Anxiety and social support, single teachers scored high. |

| Capone et al., 2019 [70] | Italy | Cros-sectional | SS = 609 | High school, middle school, elementary and primary school. 27 to 65, mean = 48.35 | The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Italian version. The Teacher Self-Efficacy Scale. | Depression: collective efficacy, all the dimensions of school climate were negatively related to depression, sex. | Women displayed higher depression and exhaustion than men. |

| Aydogan 2009 [84] | Turkey N = 83 Germany N = 78 Cyprus N = 74 | Cross-sectional | SS = 235 | High M = 38 ± 6.96, 37.9 ± 6.74, 45.8 ± 10.42 | Depression, Anxiety stressTurkish version scale DASS-42. | Depression: burnout, country of origin, job satisfaction. | Not mentioned. |

| Kidger et al., 2016 [81] | Bristol, England | Cross-sectional | 555/708/ (78.4%) | Secondary | Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale-WEMWBS) Depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-PHQ-9). Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire and the Bristol Stress and Health at Work. | Depressive symptoms: sickness absence, student attendance, dissatisfaction with work and high presenteeism, gender, supporting a colleague. Teachers’ wellbeing. | 19.4% moderate to severe depressive symptoms. |

| Bianchi et al., 2015 [99] | France | Survey | SS=627 | Primary/secondary | Depression was assessed with the 9-item depression module. | Baseline depressive symptoms predicted cases of major depression. | T1 baseline MDD 14% T 2 MDD 7%. |

| Soria-Saucedo et al., 2018 [61] | Mexico | Cross-sectional | SS = 43,845 | Female 25–74 | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9). | Severe depression: family and work stress, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking, rural/urban residents. | 7026 teachers (16%) severe depression. |

| Gluschkoff et al., 2016 [80] | Finland | Randomized selection | SS = 76 | Primary/25–63 | PHQ9. | Depressive symptoms: positive associations with effort–reward imbalance and job strain showed with depressive symptoms. Non-restorative sleep. | Not mentioned. |

| Ramberg et al., 2021 [91] | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Year 2014/16 3948/7147 (55.2%) Final SS = 2732 | Teachers | Stockholm Teacher Survey. | Depressed mood: high SOC among colleagues and stress. High SOC was linked with lower levels of stress and depressed mood variation of 4.8% for perceived stress and 2.1% for depressed mood. | Not mentioned. |

| Pohl et al., 2022 [48] | Hungary | Cross-sectional | 1817/2500 (72.7%) | High school/18–65 | BDI. | Moderate and severe depression: internet addiction. | 37.1%: no depression, 58.9% mild, 3.5% moderate and 0.6% severe depression. |

| Papastylianou et al., 2009 [3] | Greece | Cross-sectional | 562/985 (57.1%) | Primary/30–45 | The Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scales. | Depressed affect: (positive) correlation emotional exhaustion (EE). | Depressed affect: 17.86%. |

| Ratanasiripong et al., 2021 [40] | Thailand | Cross-sectional | SS = 267 | Primary/secondary | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale Thai Version (DASS). | Depression: family economics status, marital status, classroom size, relationship quality and resilience. Anxiety: family economics status, classroom size and resilience. | 3.2% of teachers had severe to extremely severe depression, 11.2% had severe to extremely severe anxiety. |

| Szigeti et al., 2017 [50] | Hungary | Cross-sectional | SS = 211 | Primary/secondary | Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale. | Depressive symptoms: teaching children with special needs, general burnout factor. | Not mentioned. |

| Baka 2015 [73] | Poland | Cross-sectional | 316/400 (79%) | Primary/secondary 22–60 | The Beck Hopelessness Scale. | Depression: work hours, job demands, general job burnout. High level of depression: interpersonal conflicts, organizational constraints and quantitative workload. | Not mentioned. |

| Othman et al., 2019 [42] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | SS = 356 | Secondary | Malay Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS). | Depression, anxiety, and stress: socio-demographic and work-related characteristics such as female, spousal help, educational status, having 1–3 children. | Depression (43.0%), anxiety (68.0%), severe to extremely severe depression 9.9%, anxiety 23.3%. 84.6% depression among those educated up to secondary or diploma level. 45% and 47.6% teachers with longest teaching experience and highest income, respectively. Lack of spousal help (55%) depressed. |

| Skaalvik et al., 2020 [18] | Norway | Longitudinal | SS = 262 | High school | Depressed mood was measured by means of a five-item scale. | Depressed mood: positively associated with emotional exhaustion. | Not mentioned. |

| Li et al., 2020 [55] | China | Cross-sectional | 1741/1795 (97%) | Preschool 18 to 48 | Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and the Perceived Stress Scale-14. | Depression: teacher weight. Depression (p < 0.001, OR = 3.08, 95% CI: 2.34–4.05) is significantly associated with burnout. | Depression was 39.9%. |

| Gosnell et al., 2021 [57] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 124/400 (31%) | Primary/secondary | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 self-care strategy questionnaire. | Depression/anxiety—self-care, being a refugee. Depression and anxiety: negative correlation with age. Younger teachers experienced higher rates of depression and anxiety than older teachers. | 14.4% depression in the severe or extremely severe clinical ranges. 41.2% anxiety levels in the severe or extremely severe clinical ranges. 10.5% nonrefugees reported anxiety at this level. |

| Capone et al., 2020 [59] | Italy | Cross-sectional | SS = 285 | High school 29–65 | The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Italian version. | Depression: flourishing or languishing. | 23.9% depression “flourishing” group, 38.7% low depression and burnout, 85.7% “languishing” had severe rating of depression. |

| Chan et al., 2002 [74] | China | Survey | SS = 83 | Secondary 22–42 | The shortened 20-item Teacher Stressor Scale (TSS). Chinese shortened version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-20). | Anxiety: support, stress. | New teachers’ highest levels of symptoms in anxiety. |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [52] | China | Survey | SS = 590 | Primary/secondary 34 ±8.11 | Self-reported mental health was measured by the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90). | Anxiety: burnout (EE and DP). | Not mentioned. |

| Nakada et al., 2016 [87] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 1006 (66.7%) | School teachers 39.7 ± 11.6 | The Japanese version of Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Job Stress Questionnaire. | Depressive symptoms: role ambiguity, role conflict, high quantitative workload, and social support from family or friends. | (20.1%) in depressive group. (79.9%) in non-depressive group. |

| Georgas et al., 1984 [79] | Greece | Cross-sectional | SS = 129 | Elementary school teachers 28–46 | Greek adaptation of the Schedule of Recent Experiences (SRE) Life Events Scale. The Manifest Anxiety Scale. | Anxiety: women only; psychosocial stress, sex differences, high correlations between psychosocial stress and anxiety, were found only for females. | Females reported more symptoms and had higher manifest anxiety than males. |

References

- Seo, J.S.; Wei, J.; Qin, L.; Kim, Y.; Yan, Z.; Greengard, P. Cellular and molecular basis for stress-induced depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleftaras, G. I katathlipsi simera. In Depression Today; Ellinika Grammata: Athens, Greece, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Papastylianou, A.; Kaila, M.; Polychronopoulos, M. Teachers’ burnout, depression, role ambiguity and conflict. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 12, 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, W.D.; Short, A.P. Teacher drug use: A response to occupational stress. J. Drug Educ. 1990, 20, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kyriacou, C.; Sutcliffe, J. Teacher stress and satisfaction. Educ. Res. 1979, 21, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Trivedi, T. Burnout in Indian teachers. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2008, 9, 320–334. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, L.A.; Espelage, D.; McMahon, S.D.; Anderman, E.M.; Lane, K.L.; Brown, V.E.; Reynolds, C.R.; Jones, A.; Kanrich, J. Violence against teachers: Case studies from the APA task force. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 1, 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, C. Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educ. Rev. 2001, 53, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen, C. Life events and depression: The plot thickens. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1992, 20, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Stress, burnout, and workaholism. In Professionals in Distress: Issues, Syndromes, and Solutions in Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Biron, C.; Brun, J.P.; Ivers, H. Extent and sources of occupational stress in university staff. Work 2008, 30, 511–522. [Google Scholar]

- King, A. Canadian Teachers Experiencing a Mental Health Crisis; Canadian Teacher’s Federation; CTF/FCE: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blix, A.G.; Cruise, R.J.; Mitchell, B.M.; Blix, G.G. Occupational stress among university teachers. Educ. Res. 1994, 36, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, A.; Newton, T. Stressful events, stressors and psychological strains in young professional engineers. J. Occup. Behav. 1985, 6, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nil, R.; Jacobshagen, N.; Schächinger, H.; Baumann, P.; Höck, P.; Hättenschwiler, J.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Burnout–An analysis of the status quo. Schweiz. Arch. Neurol. Und Psychiatr. 2010, 161, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teach. Teach. 2020, 26, 602–616. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. On the meaning of Maslach’s three dimensions of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaniol, L. Teacher burnout. Instructor 1979, 88, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Singh-Carlson, S.; Odell, A.; Reynolds, G.; Su, Y. Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction Among Oncology Nurses in the United States and Canada. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43, E161–E169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Boden, J.M.; Mulder, R.T. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.M.; Ahmed, W.S.E.; Wassif, G.O.M.; Greda, M.H.A.A. Work Related Stress, Anxiety and Depression among School Teachers in general education. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2021, 114 (Suppl. 1), hcab118.003. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C.; Rupp, A.A. A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Can. J. Educ. /Rev. Can. De L’éducation 2005, 28, 458–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Martínez-Ramón, J.P.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; García-Fernández, J.M. Latent Profiles of Burnout, Self-Esteem and Depressive Symptomatology among Teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenglass, E.R. Chapter: 33 Proactive coping, resources and burnout: Implications for occupational stress. In Research Companion to Organizational Health Psychology; Elgaronline: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; p. 503. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos, S. Job burnout and its relation tosocial anxiety in primary school teachers. Hell. J. Psychol 2012, 9, 18–44. [Google Scholar]

- Desouky, D.; Allam, H. Occupational stress, anxiety and depression among Egyptian teachers. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau, A.; Bruning, W.; Titus-Howard, T.; Ellerbeck, E.; Whittle, J.; Hall, S.; Campbell, J.; Lewis, S.C.; Munro, S. The community initiative on depression: Report from a multiphase work site depression intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 47, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lagerveld, S.E.; Bültmann, U.; Franche, R.-L.; Van Dijk, F.; Vlasveld, M.C.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Bruinvels, D.; Huijs, J.; Blonk, R.; Van Der Klink, J. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: A systematic review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2010, 20, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Besse, R.; Howard, K.; Gonzalez, S.; Howard, J. Major depressive disorder and public school teachers: Evaluating occupational and health predictors and outcomes. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2015, 20, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Seritan, A.L. How to recognize and avoid burnout. In Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, D.A.; McLaughlin, T.J.; Rogers, W.H.; Chang, H.; Lapitsky, L.; Lerner, D. Job performance deficits due to depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B.; Wei, Y.; da Luz Dias, R.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Burnout and Associated Psychological Problems Among Teachers and the Impact of the Wellness4Teachers Supportive Text Messaging Program: Protocol for a Cross-sectional and Program Evaluation Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e37934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covidence. Covidence: Better Systematic Review Management. 2020. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Katsantonis, I. Factors Associated with Psychological Well-Being and Stress: A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Psychological Well-Being and Gender Differences in a Population of Teachers. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 5, em0066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanasiripong, P.; Ratanasiripong, N.T.; Nungdanjark, W.; Thongthammarat, Y.; Toyama, S. Mental health and burnout among teachers in Thailand. J. Health Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoud, P.A.; Waroux, E.L. The Impact of Negative Affectivity on Teacher Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, Z.; Sivasubramaniam, V. Depression, anxiety, and stress among secondary school teachers in Klang, Malaysia. Int. Med. J. 2019, 26, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen, C.L.; DeMayo, R. Cognitive correlates of teacher stress and depressive symptoms: Implications for attributional models of depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1982, 91, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimian, M.J.; Santoro, T.M. Sources and Manifestations of Occupational Stress as Reported by Full-Time Special Education Teachers; SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, J.L.; Alexander, D.A. Stress among primary teachers: Individuals in organizations. Stress Med. 1992, 8, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.P.; Méndez, I.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Fernández-Sogorb, A.; García-Fernández, J.M. Profiles of burnout, coping strategies and depressive symptomatology. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okwaraji, F.; Aguwa, E. Burnout, Psychological Distress and Job Satisfaction among Secondary School Teachers in Enugu, South East Nigeria. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2015, 18, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, M.; Feher, G.; Kapus, K.; Feher, A.; Nagy, G.D.; Kiss, J.; Fejes, É.; Horvath, L.; Tibold, A. The Association of Internet Addiction with Burnout, Depression, Insomnia, and Quality of Life among Hungarian High School Teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belcastro, P.A.; Gold, R.S. Teacher stress and burnout: Implications for school health personnel. J. Sch. Health 1983, 53, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szigeti, R.; Balázs, N.; Bikfalvi, R.; Urbán, R. Burnout and depressive symptoms in teachers: Factor structure and construct validity of the Maslach Burnout inventory-educators survey among elementary and secondary school teachers in Hungary. Stress Health 2017, 33, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, U.; Parkatti, T.; Rasku, A. Occupational well-being among aging teachers in Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 1994, 38, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, D. Mental health and burnout in primary and secondary school teachers in the remote mountain areas of Guangdong Province in the People’s Republic of China. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; Beer, J. Burnout and stress, depression and self-esteem of teachers. Psychol. Rep. 1992, 71, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptáček, R.; Vnukova, M.; Raboch, J.; Smetackova, I.; Sanders, E.; Svandova, L.; Harsa, P.; Stefano, G.B. Burnout syndrome and lifestyle among primary school teachers: A Czech representative study. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019, 25, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Lv, H.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Mao, F. The prevalence and correlates of burnout among Chinese preschool teachers. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T.; Ha, C.; Learn, E. Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, N.M.; O’Neal, C.R.; Atapattu, R. Stress, mental health, and self-care among refugee teachers in Malaysia. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2021, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V.; Petrillo, G. Mental health in teachers: Relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Laurent, E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A reexamination with special focus on atypical depression. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2014, 21, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Saucedo, R.; Lopez-Ridaura, R.; Lajous, M.; Wirtz, V.J. The prevalence and correlates of severe depression in a cohort of Mexican teachers. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M.A. An Investigation into Teacher Burnout in Relation to Some Variables. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2019, 15, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, I.S.; Bianchi, R. Burnout and depression: Two entities or one? J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Rincon, A.; Howard, K.J. Anxiety in the workplace: A comprehensive occupational health evaluation of anxiety disorder in public school teachers. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2019, 24, e12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Kundra, S.; Alam, M.A.; Alam, M. Investigating stress, anxiety, social support and sex satisfaction on physical education and sports teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Manzano-García, G.; Rolland, J.-P. Is burnout primarily linked to work-situated factors? A relative weight analytic study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, M.A.; Smith Jaggars, S.E.; Faulk, K.E.; Gloria, C.T. Chronic work stress and depressive symptoms: Assessing the mediating role of teacher burnout. Stress Health 2011, 27, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduţ, C.I.; Kállay, É. Psycho-emotional and organizational aspects of burnout in a sample of Romanian teachers. Cogn. Brain Behavior. Interdiscip. J. 2011, 15, 331–358. [Google Scholar]

- Capone, V.; Joshanloo, M.; Park, M.S.-A. Burnout, depression, efficacy beliefs, and work-related variables among school teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 95, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahan, P.L.; Mahan, M.P.; Park, N.-J.; Shelton, C.; Brown, K.C.; Weaver, M.T. Work environment stressors, social support, anxiety, and depression among secondary school teachers. AAOHN J. 2010, 58, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, G.M.; Jupp, J.J.; Taylor, A.J. Work stress, distress and burnout in music and mathematics teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 64, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, L. Does job burnout mediate negative effects of job demands on mental and physical health in a group of teachers? Testing the energetic process of job demands-resources model. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W. Stress, self-efficacy, social support, and psychological distress among prospective Chinese teachers in Hong Kong. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okebukolal, P.A. The concept of schools village and the incidence of stress among science teachers. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.A.; Naing, N.N.; Daud, A.; Nordin, R.; Sulong, M.R. Prevalence and factors associated with stress among secondary school teachers in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2009, 40, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R.M. Teacher stress: The mediating role of collective efficacy beliefs. J. Educ. Res. 2010, 103, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, S.; Fakolade, O.A.; Tella, A. Perceived causes of job stress among special educators in selected special and integrated schools in Nigeria. New Horiz. Educ. 2010, 58, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Georgas, J.; Giakoumaki, E. Psychosocial stress, symptoms, and anxiety of male and female teachers in Greece. J. Hum. Stress 1984, 10, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluschkoff, K.; Elovainio, M.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L.; Hintsanen, M.; Mullola, S.; Hintsa, T. Stressful psychosocial work environment, poor sleep, and depressive symptoms among primary school teachers. EJREP 2016, 14, 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidger, J.; Brockman, R.; Tilling, K.; Campbell, R.; Ford, T.; Araya, R.; King, M.; Gunnell, D. Teachers’ wellbeing and depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors: A large cross sectional study in English secondary schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, D.; Gurpegui, M.; Moreno, O.; Fernández, M.C.; Luna, J.D.; Gálvez, R. Association of personality and work conditions with depressive symptoms. Eur. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook Jr, K.L.; Babyak, A.T. The impact of spirituality and occupational stress among middle school teachers. J. Res. Christ. Educ. 2019, 28, 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Aydogan, I.; Dogan, A.A.; Bayram, N. Burnout among Turkish high school teachers working in Turkey and abroad: A comparative study. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 7, 1249–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jepson, E.; Forrest, S. Individual contributory factors in teacher stress: The role of achievement striving and occupational commitment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 76, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, H.; Xu, J.; Wen, Y.; Fang, T. Exploring the Relationships between Resilience and Turnover Intention in Chinese High School Teachers: Considering the Moderating Role of Job Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, A.; Iwasaki, S.; Kanchika, M.; Nakao, T.; Deguchi, Y.; Konishi, A.; Ishimoto, H.; Inoue, K. Relationship between depressive symptoms and perceived individual level occupational stress among Japanese schoolteachers. Ind. Health 2016, 54, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanasiripong, P.; China, T.; Ratanasiripong, N.T.; Toyama, S. Resiliency and mental health of school teachers in Okinawa. J. Health Res. 2020, 35, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capel, S.A. Stress and burnout in teachers. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 1992, 15, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, I.S. A longitudinal study of occupational stressors and depressive symptoms in first-year female teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1992, 8, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, J.; Låftman, S.B.; Nilbrink, J.; Olsson, G.; Toivanen, S. Job strain and sense of coherence: Associations with stress-related outcomes among teachers. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Mayor, E.; Laurent, E. Burnout-depression overlap: A study of New Zealand schoolteachers. New Zealand J. Psychology 2016, 45, 362. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, E. Mobbing and stress. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2015, 11, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, A.A.; Naing, N.N.; Daud, A.; Nordin, R. Work related depression among secondary school teachers in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Int. Med. J. 2008, 15, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Noh, H.; Jang, Y.; Park, Y.M.; Lee, S.M. A longitudinal examination of the relationship between teacher burnout and depression. J. Employ. Couns. 2013, 50, 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gelban, K.S. Psychiatric morbidity among Saudi secondary schoolteachers. Neurosci. J. 2008, 13, 288–290. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Hu, Q.; Wang, P.; Lei, L.; Jiang, S. The relationship between phubbing and the depression of primary and secondary school teachers: A moderated mediation model of rumination and job burnout. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Schonfled, S.; Laurent, E. Burnout does not help predict depression among French school teachers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2015, 41, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Liang, L.; Chutiyami, M.; Nicoll, S.; Khaerudin, T.; Ha, X.V. COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety, stress, and depression among teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work 2022, 1–25, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.F.O.; Cobucci, R.N.; Lima, S.C.V.C.; de Andrade, F.B. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Medicine 2021, 100, e27684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Oluwasina, F.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, V.I.O. A Scoping Review on the Prevalence and Determinants of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Military Personnel and Firefighters: Implications for Public Policy and Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradus, J.L. Epidemiology of PTSD. National Center for PTSD (United States Department of Veterans Affairs). 2007. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/epidemiology.asp (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Mukhopadhyay, S. Working status and stress of middle class women of Calcutta. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1989, 21, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, W.P.; Garland, B.E. Occupational stress and burnout between male and female police officers: Are there any gender differences? Polic. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2007, 30, 672–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Prel, J.B.; Peter, R. Work-family conflict as a mediator in the association between work stress and depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional evidence from the German lidA-cohort study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padkapayeva, K.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; Bielecky, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Mustard, C.; Brisson, C.; Smith, P. Gender/Sex Differences in the Relationship between Psychosocial Work Exposures and Work and Life Stress. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2018, 62, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Torres, P.; Araque-Padilla, R.A.; Montero-Simó, M.J. Job stress across gender: The importance of emotional and intellectual demands and social support in women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardon, M.C. Stress and ageing interactions: A paradox in the context of shared etiological and physiopathological processes. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 54, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chughati, F.D.; Perveen, U. A study of teachers workload and job satisfaction in public And private schools at secondary level in Lahore city Pakistan. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 2, 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bounds, C.; Jenkins, L.N. Teacher-directed violence and stress: The role of school setting. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 22, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, K.; Fernández-Martín, F.D.; Szotkowski, R.; Gómez-García, G.; Mikulcová, K. Behaviour of Children and Adolescents and the Use of Mobile Phones in Primary Schools in the Czech Republic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felisoni, D.D.; Godoi, A.S. Cell phone usage and academic performance: An experiment. Comput. Educ. 2018, 117, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; Pérez-Moreno, M.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.G.; Roberts, A.M.; Zarrett, N. A Brief Mindfulness-Based Intervention (bMBI) to Reduce Teacher Stress and Burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ 2021, 100, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner-Lane, R.; Patton, W. Determinants of burnout among public hospital nurses. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.A.; Spence Laschinger, H.K. The influence of frontline manager job strain on burnout, commitment and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Nedelec, L.; Carlasare, L.E.; Shanafelt, T.D. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e209385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Lai, C. Mental health level and happiness index among female teachers in Malaysia. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 2020, 23, 231–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peele, M.; Wolf, S. Predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms among teachers in Ghana: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 253, 112957. [Google Scholar]

- Battams, S.; Roche, A.M.; Fischer, J.A.; Lee, N.K.; Cameron, J.; Kostadinov, V. Workplace risk factors for anxiety and depression in male-dominated industries: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 983–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai-Pak, M.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Poghosyan, L. Poor work environments and nurse inexperience are associated with burnout, job dissatisfaction and quality deficits in Japanese hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 3324–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrupp, M. Secondary Teaching, Social Contexts and the Lingering Politics of Blame; Waipuna Hotel and Conference Centre: Auckland, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.W.; Hui, E.K. Stress, Suppport and Psychological Symptoms Among Guidance and Non-Guidance Secondary School Teachers in Hong Kong. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1998, 19, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valosek, L.; Wendt, S.; Link, J.; Abrams, A.; Hipps, J.; Grant, J.; Nidich, R.; Loiselle, M.; Nidich, S. Meditation effective in reducing teacher burnout and improving resilience: A randomized controlled study. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 627923. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrasch, R.; Berger, R.; Grossman, D. Mindfulness and compassion as key factors in improving teacher’s well being. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Agyapong, V.I.; Mrklas, K.; Juhás, M.; Omeje, J.; Ohinmaa, A.; Dursun, S.M.; Greenshaw, A.J. Cross-sectional survey evaluating Text4Mood: Mobile health program to reduce psychological treatment gap in mental healthcare in Alberta through daily supportive text messages. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Gusnowski, A.; Shalaby, R.; Mrklas, K.; Li, D.; Urichuk, L.; Snaterse, M.; Surood, S.; et al. Closing the Psychological Treatment Gap During the COVID-19 Pandemic With a Supportive Text Messaging Program: Protocol for Implementation and Evaluation. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e19292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Shalaby, R.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Noble, J.M.; Gusnowski, A.; Mrklas, K.; Li, D.; Snaterse, M.; Surood, S.; et al. Mental Health Outreach via Supportive Text Messages during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Improved Mental Health and Reduced Suicidal Ideation after Six Weeks in Subscribers of Text4Hope Compared to a Control Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, N.; Ahmad, F.; El Morr, C.; Ritvo, P. Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety and stress: A survey with university students. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2019, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, S.T.; Kim, S. Meta-regression analyses of relationships between burnout and depression with sampling and measurement methodological moderators. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021, 2, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I.; Benevene, P.; Fiorilli, C.; D’amelio, F.; Pozzi, G. Working conditions and mental health in teachers: A preliminary study. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 530–532. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Burnout | Stress | Anxiety | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlates | Citations | Correlates | Citations | Correlates | Citations | Correlates | Citations | |

| Demographic Correlates | ||||||||

| Sex | ✓ | [40,47,51,52,53,54,55,63,67,68,72,73] | ✓ | [42,53,57,66,74,75,76,77,78] | ✓ | [42,79] | ✓ | [28,41,52,63,74,80] |

| Age | ✓ | [40,47,51,52,53,54,55,63,67,68,72,73] | ✓ | [42,53,57,66,74,75,76,77,78] | ✓ | [28,79] | ✓ | [28,42,51,70,81,82] |

| Gender | ✓ | [40,47,51,52,53,54,55,63,67,68,72,73] | ✓ | [42,53,57,66,74,75,76,77,78] | ✓ | [42,79] | ✓ | [28,42,51,70,81,82] |

| Marital Status | ✓ | [40,47,51,52,53,54,55,63,67,68,72,73] | ✓ | [66] | ||||

| Years taught/Teaching Experience | ✓ | [40,47,51,52,53,54,55,63,67,68,72,73] | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [42] | ||

| Educational Level | ✓ | [42] | ||||||

| Family economics status and income | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [40] | ||

| Teachers’ weight | ✓ | [55] | ||||||

| Spirituality | ✓ | [83] | ||||||

| Number of children | ✓ | [63] | ||||||

| Country of participant | ✓ | [39] | ||||||

| School and professional correlates | ||||||||

| Work factors/job strain | ✓ | [18,42,67,84] | ✓ | [42,45,77,78] | ✓ | [42] | ✓ | [42,50,51,80] |

| Subjects/Level taught | ✓ | [7,51,72] | ✓ | [75,78,85] | ✓ | [51,65] | ✓ | [42,50,51,80] |

| School Climate/Organizational Justice | ✓ | [70] | ||||||

| Job Satisfaction/Absenteeism | ✓ | [39,43,82] | ✓ | [51,65] | ✓ | [42,50,51,80,81] | ||

| Student type/Behavior | ✓ | [45,77] | ✓ | [42,50,51,80] | ||||

| Teaching special needs | ✓ | [78] | ✓ | [50] | ||||

| Lack of students’ Progress | ✓ | [78,85] | ||||||

| Violence/Verbal Abuse from Students | ✓ | [82] | ||||||

| Dealing with parent | ✓ | [45] | ||||||

| Class Management | ✓ | [45] | ||||||

| High job demands and workload | ✓ | [73,86] | ✓ | [42,53,57,74,75,76,77,78] | ✓ | [73,87] | ||

| Resilience/Class size | ✓ | [40,86] | ✓ | [78,85,88] | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [40] |

| Role conflict, Role ambiguity Role Clarity | ✓ | [3,89] | ✓ | [89] | ✓ | [87] | ||

| Collective efficacy, school climate, and organizational justice | ✓ | [70] | ✓ | [70,90] | ||||

| Student motivation and time pressure | ✓ | [18] | ||||||

| School type/Income | ✓ | [40,70] | ✓ | [82] | ||||

| Interpersonal conflict and organizational constraints | ✓ | [73] | ||||||

| Job seniority | ✓ | [73] | ||||||

| High sense of coherence among colleagues | ✓ | [91] | ✓ | [91] | ||||

| Student Attendance | ✓ | [81] | ||||||

| Social and other correlates | ||||||||

| Dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative responses, and pessimistic attributions. | ✓ | [92] | ✓ | [92] | ||||

| Exercise | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [61] | ||||

| Relationship quality | ✓ | [40] | ✓ | [40] | ||||

| Presenteeism | ✓ | [81] | ||||||

| Absenteeism | ✓ | [65] | ✓ | [31] | ||||

| Non-restorative sleep | ✓ | [80] | ||||||

| Effort-reward imbalance | ✓ | [42,50,51,80] | ||||||

| Quality of life | ✓ | [31] | ||||||

| Psychological distress | ✓ | [74] | ||||||

| Communication | ✓ | [58] | ||||||

| Overcommitment | ✓ | [50] | ✓ | [85] | ||||

| Flourishing/Languishing | ✓ | [59] | ||||||

| Being a Refugee | ✓ | [57] | ||||||