Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Is Autonomy a Cultural Universal?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Interview Questions

- Paternalism/El Paternalismo: A relationship in which the physician has substantial/most control and authority over the patient’s healthcare decisions./Una relación en la que el médico tiene un control sustancial/ mayor y más autoridad sobre las decisiones de atención médica del paciente.

- Autonomy/La Autonomía: A relationship in which the patient has substantial/most control and authority over their own healthcare decisions./Una relación en la que el paciente tiene un control sustancial/ mayor y más autoridad sobre sus propias decisiones de atención médica.

2.3. Methods of Analysis

3. Results

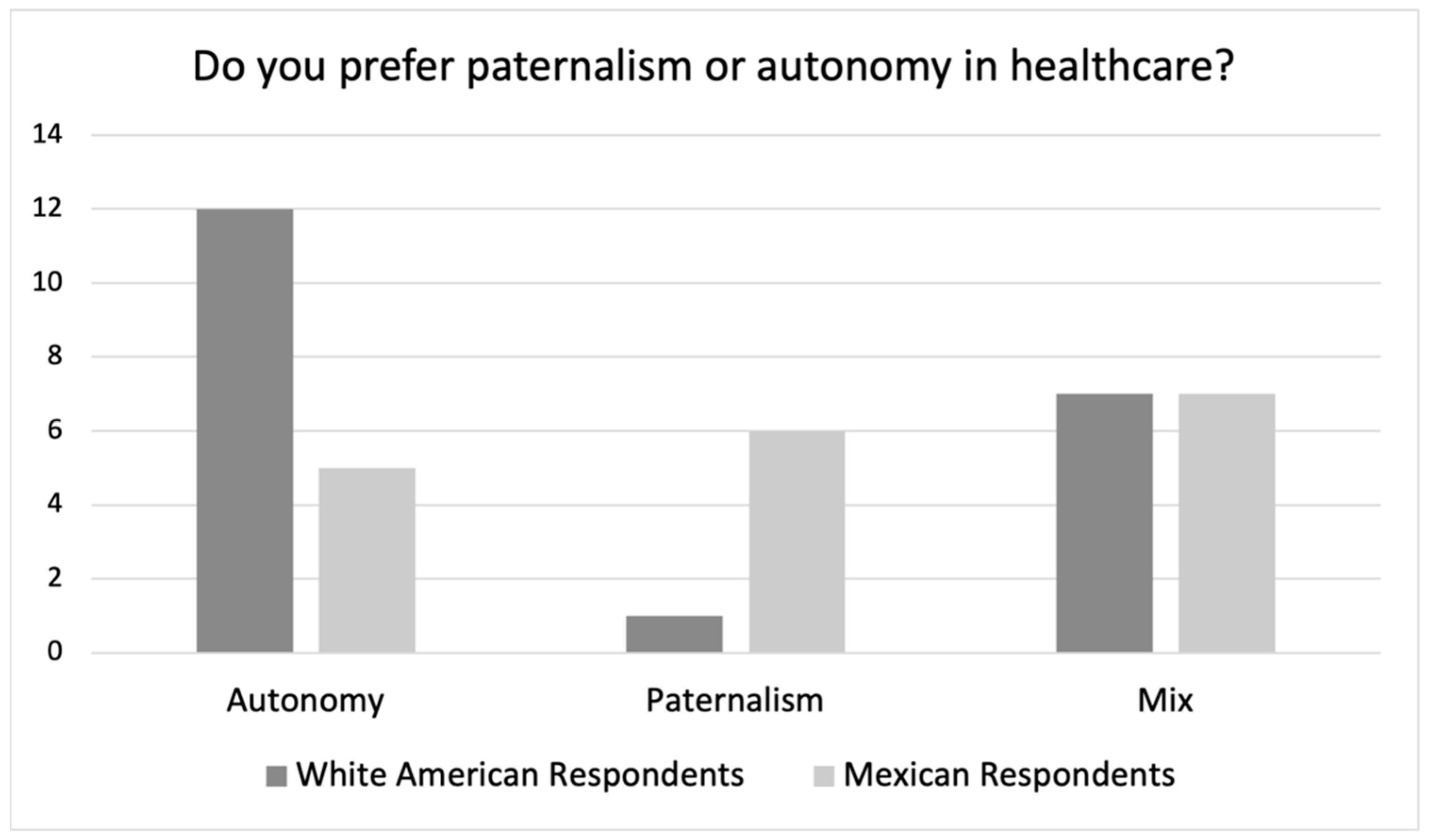

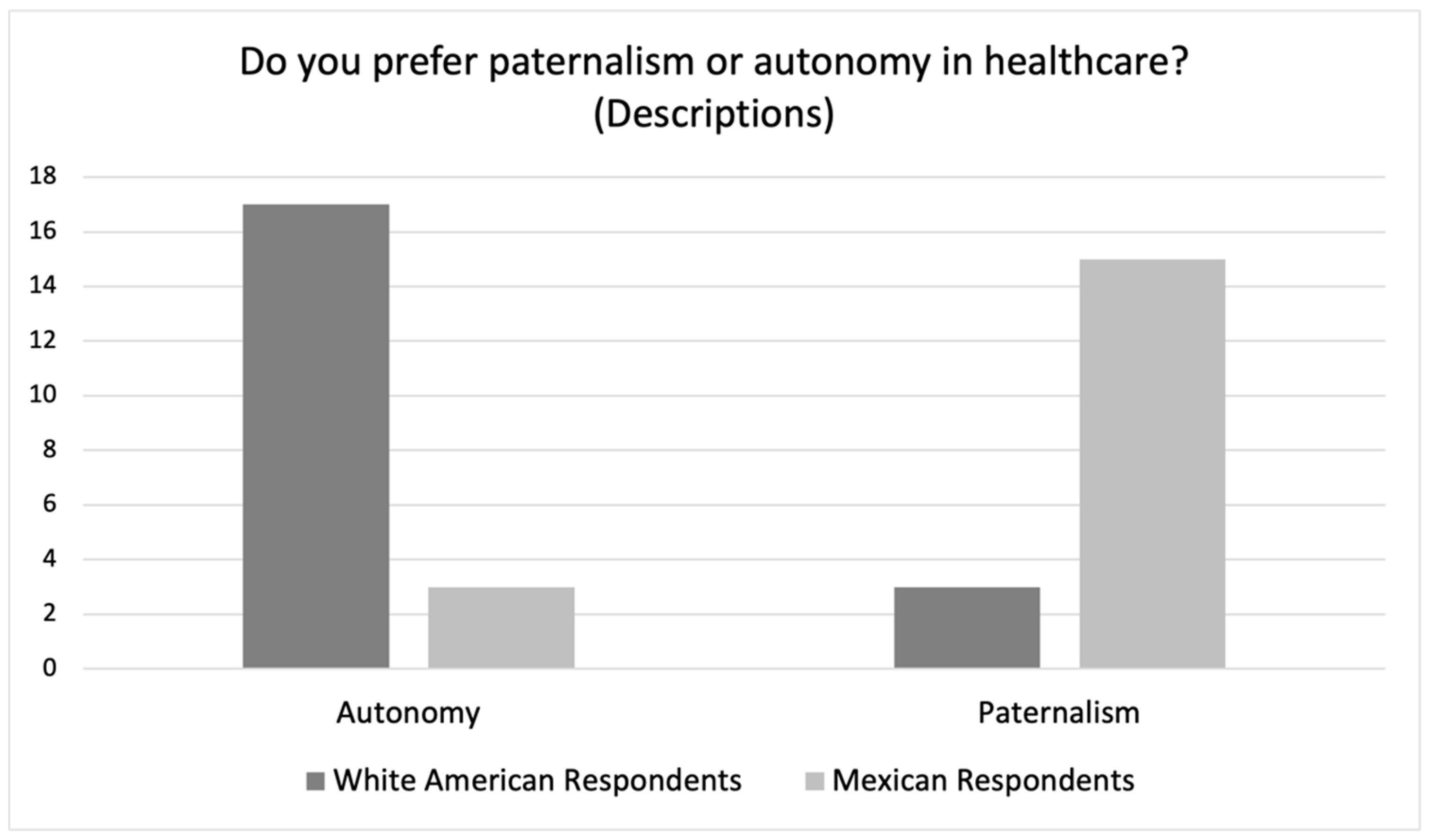

3.1. Group Preferences Data

3.1.1. Group Preferences: White American Respondents

3.1.2. Group Preferences: Mexican Respondents

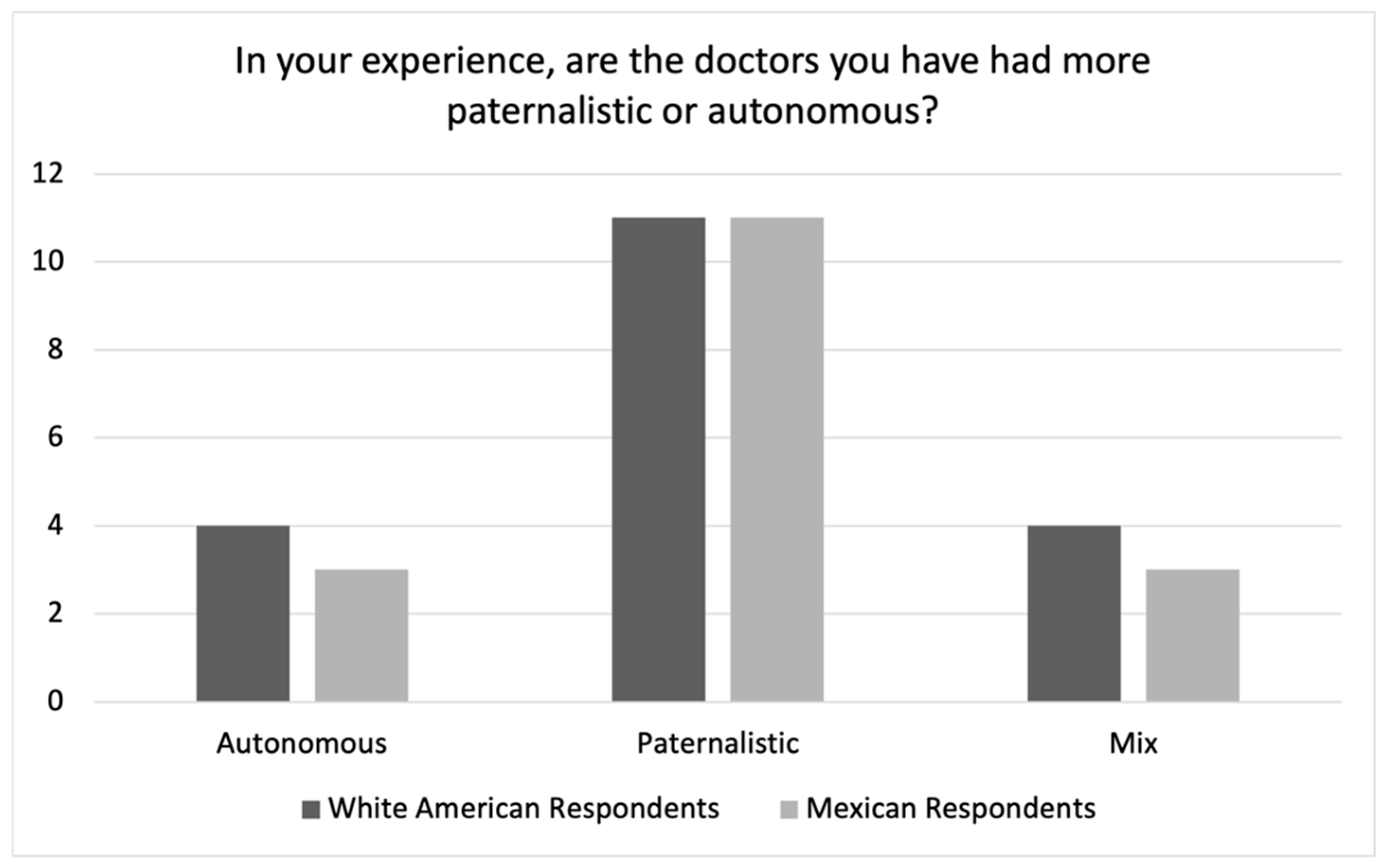

3.2. Group Experiences Data

3.2.1. White American Respondents Experiences of Paternalism with U.S. Physicians

3.2.2. Qualitative Data Explaining Respondents’ Definitions of Paternalism

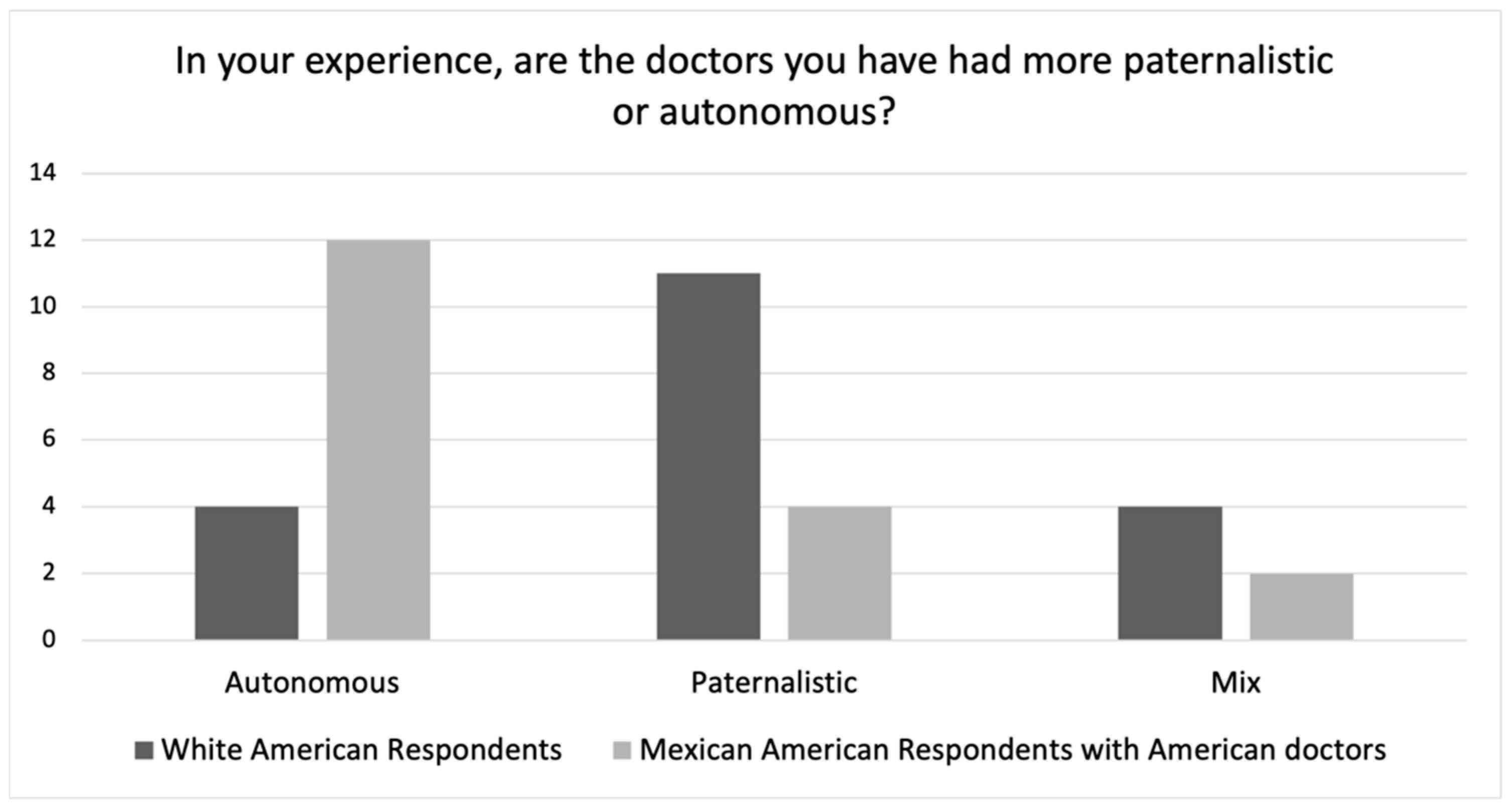

Mexican American Respondents’ Experiences with American and Mexican Physicians

White American Respondents’ Experiences with American Physicians

Mexican Respondents’ Experiences with Mexican Physicians

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Preferences for Physician Paternalism vs. Patient Autonomy

4.2. Cultural Differences in Experiences with Physician Paternalism vs. Patient Autonomy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions

- 1

- How many times would you say you’ve gone to see a doctor in the past year?

- 2

- Do you usually go to the same doctor or do you see different doctors?

- 3

- What is the ethnic background of the doctor that you usually see?

- 4

- Describe the relationship that you have with the doctor you usually see. (Probes: Do they know much about you? Your family? Do you know much about them?)

- 5

- How would you describe the personality of the doctor you usually see?

- 6

- When your doctor gives you a diagnosis and a treatment plan:

- Does your doctor consult with you when deciding on a treatment plan? Which do you prefer (i.e., do you prefer that your doctor give you choices between treatments or would you prefer if they make the treatment decisions)?

- At the end of the day, who makes the final treatment decision, you or your doctor or both?

- Do you prefer to play a bigger part in the treatment decision making process, or do you prefer for your doctor to play a bigger part in the treatment decision making process?

- Do you prefer for your doctor to know a lot about you personally?

- Is it weird if they ask about aspects of your personal life that are unrelated to the reason you are seeing the doctor? Do you prefer it when your doctor asks about your personal life?

- Is it okay for your doctor to give you advice about aspects of your personal life that are unrelated to the reasons you are seeing the doctor? Do you prefer doctors that give such advice?

- Have you ever questioned your doctor’s treatment decision? For example, have you ever NOT taken a medicine that your doctor prescribed? If so, why did you choose not to? If not, can you imagine a situation in which you would not follow your doctor’s orders for treatment?

- 7

- Can you briefly describe the ethnic/cultural background of doctors that you have liked in the U.S. (or Mexico)? What was good about those experiences?

- 8

- Can you briefly describe the ethnic/cultural background of doctors that you have not liked in the U.S. (or Mexico)? What was bad about those experiences?

- 9

- For doctors with different/ethnic cultural backgrounds, of the doctors that you liked, are any of them from ethnic/cultural backgrounds different from your own?

- 10

- (For American respondents) Do you have any Latinx friends?

- Have they ever shared anything with you about their experiences (good or bad) with doctors? If so, was the doctor American or another nationality/ethnicity? What did they say about it?

Hypotheticals

| 1 | 2,3 | 4 | 5,6 | 7 | ||||

| perfectly normal | in between | a little WAUS | in between | highly WAUS |

- 11

- You are taking a medication that could cause depression and you tell your doctor that you don’t want to take the depression medication and your doctor tells you “if you get depressed, you must take the medication”. Why WAUS or why not?

- 12

- You go to the doctor with your son and his hair is long and shaggy and your doctor tells you to get your son a haircut. Why WAUS or why not?

- 13

- Your doctor tells you that you need to lose weight and then says “you have to exercise everyday”. Why WAUS or why not?

- 14

- During a regular check-up, your doctor tells you not to look at “very ugly things” (i.e., pornography) on the internet. Why WAUS or why not?

- 15

- (Question only for women who have been pregnant) After an ultrasound, your doctor wipes off your abdomen and zips and buttons up your pants for you. Why WAUS or why not?

- 16

- You go to the doctor with a particular concern (e.g., swelling in your feet) and your doctor asks you whether or not you want to take a medication (e.g., diuretic pills that help remove the liquid), would you think that is unusual? Why WAUS or why not?

- If you then agreed to the prescription and then you experienced side effects, would you be more or less likely to keep taking the medication if he asked if you wanted to take the medication rather than if he had told you “you must take the medication”?

- 17

- Imagine you are a young single adult and go to your doctor and he tells you that you must get married. Why WAUS or why not?

- 18

- Would you think it strange if you went to your annual check-up and your weight had been consistently increasing and your overweight doctor said to you “I’m not very good to talk about weight control to anybody” and then gave you basic advice about a good diet? Why WAUS or why not? Would you be more or less likely to follow his instructions as compared to if the doctor had said “you are overweight and need to watch what you eat and make sure that you have a well-balanced diet”? Would it have seemed more strange if they were to have said that?

- 19

- In your experience with American (or Mexican) doctors,

- RE: decision making, do they tell you what they want to do or do they give you information and let you decide what the best course of action is?

- RE: involvement/care, do they tend to know a lot about you personally? Do they ask a lot about you personally that may not be directly related to the reason you are seeing them?

- RE: advice-giving, do they tend to give you advice about your personal life and personal affairs even if it is not relevant to the reason you are seeing them?

- Define paternalism and autonomy

- 20

- Do you prefer paternalism or autonomy in healthcare?

- Why?

- 21

- In your experience, are mainstream American (or Mexican) doctors more paternalistic or autonomous?

- 22

- (IF yes to 10) In your experience/understanding, are Mexican doctors more paternalistic or autonomous?

Appendix B. Codebook 1

- Doctor Professionalism

- Lack of Professionalism: American

- Lack of Professionalism: Mexican

- American doctors

- Mexican doctors

- Concerns about paternalism

- American doctors

- Mexican doctors

- Concerns about autonomy

- Money concerns

- Lack of authority

- Actions showing lack of authority

- Interpretation of actions

- Support for paternalism

- American support

- Mexican support

- Authority of doctor

- Actions showing authority of doctor

- Interpretation of actions showing authority

- Confident (vs. Uncertain or unsure)

- Decision-making

- Support for autonomy

- American support

- Mexican support

- Shared decision-making

- Mexican doctors are more paternalistic

- Actions supporting paternalism of Mexican doctors

- Interpretation of actions supporting paternalism of Mexican doctors

- Care1-Physical and emotional caring

- Actions demonstrating lack of care1

- Actions demonstrating care1

- Interpretations of actions demonstrating care1

- Care2-Personal business, moral advice

- Actions demonstrating care2

- Interpretation of actions demonstrating care2

Appendix C. Codebook 2

- Characterizations of paternalism/autonomy

- Autonomy-informed decision-making

- Autonomy-doctor and patient as equals (collaboration)

- Autonomy-control over body

- Paternalism-authoritative doctor

- Arrogant

- Dismissive

- Paternalism-familism

- Care for well-being

- Paternalism-doctor’s expertise

- Patient decides if they agree with doctor

- Patient admits they are unqualified

- Autonomy

- People who say they prefer Autonomy, but describe something else

- Describe paternalism

- Describe mix

- People who prefer autonomy (numbers and story)

- Mexican

- Mexican-American

- American

- Paternalism

- People who say they prefer Paternalism but describe something else

- Describe autonomy

- Describe mix

- People who prefer paternalism (numbers and story)

- Mexican

- Mexican-American

- American

- Mix

- People who say P/A but give details as Mix

- Mix in middle

- Mix leaning toward autonomy

- Mix leaning toward paternalism

- Mix stories

- Mix preference

- Narratives

- Very influential experiences

- Paternalism experiences

- Mix experiences

- Negative experiences

- Positive experiences

- Autonomy experiences

- Mix experiences

- Negative experiences

- Positive experiences

References

- Jennings, B. Autonomy. In The Oxford Handbook of Bioethics; Steinbock, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J. Getting Obligations Right: Autonomy and Shared Decision Making. J. Appl. Philos. 2020, 37, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B. Reconceptualizing Autonomy: A Relational Turn in Bioethics. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2016, 46, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, R. Respect for cultural diversity and pluralism. In Handbook of Global Bioethics; ten Have, H.A.M.J., Gordijn, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandman, L.; Munthe, C. Shared decision-making and patient autonomy. Theor Med Bioeth 2009, 30, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C. The Practice of Autonomy: Patients, Doctors, and Medical Decisions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, M. Healthcare Decision-Making and the Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Open WorldCat; Available online: http://www.myilibrary.com?id=296631 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.M.; Cribb, A.; McCaffery, K. Supporting Patient Autonomy: The Importance of Clinician-Patient Relationships. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coggon, J.; Miola, J. Autonomy, Liberty, and Medical Decision-Making. Camb. Law J. 2011, 70, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.; Childress, J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics: Marking Its Fortieth Anniversary. Am. J. Bioeth. 2019, 19, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.R. Autonomy, Paternalism, and Justice: Ethical Priorities in Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, D.R. Elder Abuse and Vulnerability: Avoiding Illicit Paternalism in Healthcare, Medical Research, and Life. Ethics Med. Public Health 2015, 1, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A. Paternalism or Partnership? BMJ 1999, 319, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Elkredge, US, 1979. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Ten, H.H.; Stanton-Jean, M. (Eds.) The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights: Background, Principles and Application; Unesco: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G.A.; Whiffen, L.H. Can Physicians Demonstrate High Quality Care Using Paternalistic Practices? A Case Study of Paternalism in Latino Physician–Patient Interactions. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Angeles-Llerenas, A.; Rodríguez-Valentín, R.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Domínguez-Esponda, R.; Astudillo-García, C.I.; Madrigal-de León, E.; Katz, G. Communication Patterns in the Doctor–Patient Relationship: Evaluating Determinants Associated with Low Paternalism in Mexico. BMC Med. Ethics 2020, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shweder, R.A. Moral realism without the ethnocentrism: Is it just a list of empty truisms? In Human Rights with Modesty: The Problem of Universalism; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, L.A. The cultural development of three fundamental moral ethics: Autonomy, community, and divinity. Zygon® 2011, 46, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.; Green, A.; Carillo, J.E. The challenges of cross-cultural healthcare-diversity, ethics, and the medical encounter. In Bioethics Forum; Midwest Bioethics Center: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000; Volume 16, pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, R.A.; Rosenthal, S.B. Toward a new understanding of moral pluralism. Bus. Ethics Q. 1996, 6, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; Sánchez-Izquierdo, M.; Olmos, R.; Huici, C.; Ribera Casado, J.M.; Cruz Jentoft, A. Paternalism vs. autonomy: Are they alternative types of formal care? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkler, K. Physicians at Work, Patients in Pain: Biomedical Practice and Patient Response in Mexico; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.; Cribb, A.; Entwistle, V.A. Defining What is Good: Pluralism and Healthcare Quality. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2019, 29, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.J. Pragmatic Ethics, Sensible Care: Psychiatry and Schizophrenia in North India; The University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zivkovic, T. Lifelines and end-of-life decision-making: An anthropological analysis of advance care directives in cross-cultural contexts. Ethnos 2021, 86, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, I. Blind trust in the care-giver: Is paternalism essential to the health-seeking behavior of patients in Sub-Saharan Africa? Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2015, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujewe, S.J. Ought-onomy and Mental Health Ethics: From “Respect for Personal Autonomy” to “Preservation of Person-in-Community” in African Ethics. Philos. Psychiatry Psychol. 2018, 25, E-45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibu, S. Ethical and cultural considerations in informed consent in Botswana. Nurs. Ethics 2007, 14, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addissie, A.; Tesfaye, M. Ethiopia. In Handbook of Global Bioethics; ten Have, H.A.M.J., Gordijn, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, D. Doctor-Patient Communication in Government Hospitals in JAMAICA. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blackhall, L.J.; Murphy, S.T.; Frank, G.; Michel, V.; Azen, S. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. Jama 1995, 274, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, G.; Blackhall, L.J.; Michel, V.; Murphy, S.T.; Azen, S.P.; Park, K. A discourse of relationships in bioethics: Patient autonomy and end-of-life decision making among elderly Korean Americans. Med. Anthropol. Q. 1998, 12, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q. Doctor-Patient Communication and Patient Satisfaction: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study between China and the U.S. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2010. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database. (Order No. 3444876). [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Simon, A. East meets West: Cross-cultural perspective in end-of-life decision making from Indian and German viewpoints. Med. Health Care Philos. 2008, 11, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, R.; Sakai, A. The physician–patient relationship and medical ethics in Japan. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 1994, 3, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claramita, M.; Nugraheni, M.D.; van Dalen, J.; van der Vleuten, C. Doctor–patient communication in Southeast Asia: A different culture? Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2013, 18, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadiman, A. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moazam, F. Families, patients, and physicians in medical decision-making: A Pakistani perspective. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2000, 30, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.A. Applicability of the principle of respect for autonomy: The perspective of Turkey. J. Med. Ethics 2007, 33, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, D. The intellectual basis of bioethics in southern European countries. Bioethics 1993, 7, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Vun, M.; Mcleod, L. Needs and experiences of non-English-speaking hospice patients and families in an English-speaking country. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med.® 2001, 18, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.B. The plurality of Chinese and American medical moralities: Toward an interpretive cross-cultural bioethics. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2000, 10, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veatch, R.M. The ethics of critical care in cross-cultural perspective. In Ethics and Critical Care Medicine; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Payne-Jackson, A.; Alleyne, M.C. Jamaican Folk medicine: A Source of Healing; University of West Indies Press: Mona, Jamaica, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.L. Confucian moral thinking. Philos. East West 1995, 45, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. Awareness of Dying; Transaction Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, S. Dying of awareness: The theory of awareness contexts revisited. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano-Ponce, E.; Angeles-Llerenas, A.; Alvarez-del Río, A.; Salazar-Martínez, E.; Allen, B.; Hernández-Avila, M.; Kraus, A. Ethics and Communication between Physicians and Their Patients with Cancer, HIV/AIDS, and Rheumatoid Arthritis in Mexico. Arch. Med. Res. 2004, 35, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colmenares-Roa, T.; Huerta-Sil, G.; Infante-Castañeda, C.; Lino-Pérez, L.; Alvarez-Hernández, E.; Peláez-Ballestas, I. Doctor–Patient Relationship Between Individuals With Fibromyalgia and Rheumatologists in Public and Private Health Care in Mexico. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1674–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenta-Arellano, S.; Muños-Hernández, J.A.; Pavón-León, P.; Coronel-Brizio, P.G.; Gutiérrez-Alba, G. An Overview on the Promotion on Patient-Centered Care and Shared Decision-Making in Mexico. Z. Für Evidenz Fortbild. Und Qual. Im Gesundh. 2022, 171, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Pagan, J.A.; Rodriguez-Oreggia, E. The Decision-Making Process of Health Care Utilization in Mexico. Health Policy 2005, 72, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, R. Against Relativism: Cultural Diversity and the Search for Ethical Universals in Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, L.; Gamez-Nava, J.I.; Rodríguez-Arreola, B.E.; Cox, V.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. Doctor-Patient Interactions in Mexican Patients with Rheumatic Disease. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009, 15, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez, J.Á.; Carreño, J.P.S.; Rojas, J.A.V. Percepción de Los Pacientes Acerca de La Empatía de Las Enfermeras En Monterrey (México) = Perception of Patients about the Empathy of Nurses in Monterrey (Mexico). Rev. Española De Comun. En Salud 2018, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubova, S.V.; Guanais, F.C.; Pérez-Cuevas, R.; Canning, D.; Macinko, J.; Reich, M.R. Attributes of Patient-Centered Primary Care Associated with the Public Perception of Good Healthcare Quality in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and El Salvador. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| White American | Mexican American | Mexican | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Number | Location | Number | Location | Number |

| California | 3 | California | 2 | Hidalgo | 16 |

| Idaho | 1 | Kansas | 2 | Nuevo Leon | 1 |

| Texas | 1 | New Mexico | 2 | Tamaulipas | 2 |

| Utah | 10 | Texas | 2 | Veracruz | 1 |

| Washington | 5 | Utah | 5 | ||

| Washington | 7 | ||||

| Total | 20 | 20 | 20 | ||

| Interview Language | Gender | Age | Interview Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Spanish | English | Female | Male | Range | Mean | Average (min:sec) |

| White American | 0 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 30–58 | 47.5 | 36:39 |

| Mexican American | 3 | 17 | 15 | 5 | 31–60 | 48.6 | 39:27 |

| Mexican | 20 | 0 | 15 | 5 | 33–65 | 48.7 | 30:42 |

| Total | 23 | 37 | 42 | 18 | 30–65 | 48.2 | 35:36 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, G.A.; Segura, J.; Cruz, D.; Arnita, C.; Whiffen, L.H. Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710663

Thompson GA, Segura J, Cruz D, Arnita C, Whiffen LH. Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710663

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Gregory A., Jonathan Segura, Dianne Cruz, Cassie Arnita, and Leeann H. Whiffen. 2022. "Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710663

APA StyleThompson, G. A., Segura, J., Cruz, D., Arnita, C., & Whiffen, L. H. (2022). Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10663. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710663