Investigating Employment Quality for Population Health and Health Equity: A Perspective of Power

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Employment Quality, Health, and Health Equity

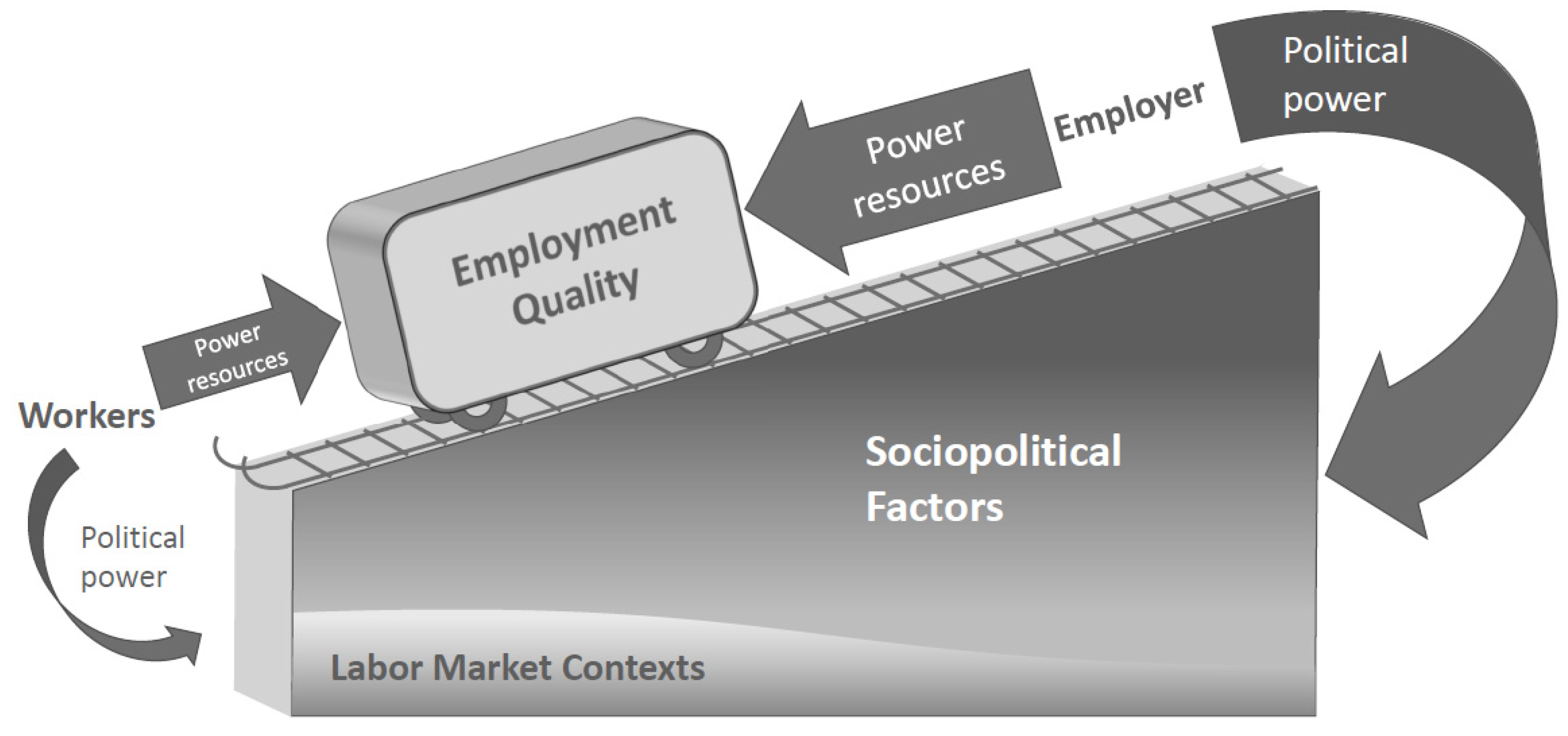

3. Power as a Key to Conceptualizing EQ

4. Recognizing Power and Its Social Configuration as It Relates to Health: An Allegory

4.1. Power That Creates an Uneven Playing Field

4.2. Power That Operates on an Uneven Playing Field

4.3. Other Axes of Power That Shape EQ

4.4. Understanding EQ and Health from a Perspective of Power

5. EQ research Approaches for Incorporating a Perspective of Power

| Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Using theory to study how EQ is formed and related to health/health inequity | To organize research endeavors and build shared language and understandings of complex and dynamic phenomena [68,69]. The use of theory is important in exploratory, explanatory, and confirmatory studies [90]. |

| 2. Expanding focus from individuals to social contexts in which individuals experience EQ | Relying exclusively on individual-level data obscures the contexts that create power, or lack thereof, which in turn shape health inequity [3,38,51]. |

| 3. Measuring EQ conceptually in context | Conceptual agreement exists on what is relevant to EQ and what characterizes it [4,5,10,64,65,67], but variables to best represent these will be specific to time, place, and societal structure. Conceptual, rather than literal, alignment may be more informative. |

| 4. Studying EQ as a structural determinant of health inequity | EQ patterns across individual or worker group characteristics [24,25,26,27] suggest that poor EQ may explain health inequity. Focusing on social structure and processes that distribute EQ unevenly may be useful in understanding health inequity. |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, H.K. A short history of occupational health. J. Public Health Policy 2001, 22, 34–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gochfeld, M. Chronologic history of occupational medicine. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 47, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, K.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, D.; Chen, I.-C.; Benavides, F.G. Sociopolitical values and social institutions: Studying work and health equity through the lens of political economy. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Amable, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Tarafa, G.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodin, T.; Çağlayan, Ç.; Garde, A.H.; Gnesi, M.; Jonsson, J.; Kiran, S.; Kreshpaj, B.; Leinonen, T.; Mehlum, I.S.; Nena, E. Precarious employment in occupational health—An OMEGA-NET working group position paper. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2020, 46, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanroelen, C. Employment Quality: An Overlooked Determinant of Workers’ Health and Well-being? Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2019, 63, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahonen, E.Q.; Fujishiro, K.; Cunningham, T.; Flynn, M. Work as an inclusive part of population health inequities research and prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C. Employment and working conditions as health determinants. In Improving Equity in Health by Addressing Social Determinants; Lee, J.H., Sadana, R., Eds.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, D.; McClelland, C. Job Quality in Growing and Declining Economic Sectors of the EU; European Commission, European Research Area: Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Julià, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Bosmans, K.; Van Aerden, K.; Benach, J. Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. Int. J. Health Serv. 2017, 47, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz de Bustillo, R.; Fernández-Macías, E.; Esteve, F.; Antón, J.-I. E pluribus unum? A critical survey of job quality indicators. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2011, 9, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffgen, G.; Sischka, P.E.; Fernandez de Henestrosa, M. The quality of work index and the quality of employment index: A multidimensional approach of job quality and its links to well-being at work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Job quality and precarious work: Clarifications, controversies, and challenges. Work. Occup. 2012, 39, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koranyi, I.; Jonsson, J.; Rönnblad, T.; Stockfelt, L.; Bodin, T. Precarious employment and occupational accidents and injuries—A systematic review. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2018, 44, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancea, M.; Utzet, M. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: A scoping study on social determinants. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peckham, T.; Fujishiro, K.; Hajat, A.; Flaherty, B.P.; Seixas, N. Evaluating employment quality as a determinant of health in a changing labor market. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, N. Workers are people too: Societal aspects of occupational health disparities—An ecosocial perspective. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritschard, G.; Bussi, M.; O’Reilly, J. An index of precarity for measuring early employment insecurity. In Sequence Analysis and Related Approaches: Innovative Methods and Applications; Ritschard, G., Studer, M., Eds.; Springer: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, J.-C. La précarité, une catégorie française à l’épreuve de la comparaison internationale. Revue Française Sociologie 2005, 46, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, W. Power resources approach vs. action and conflict: On causal and intentional explanations in the study of power. Sociol. Theory 1985, 3, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, J.; Van Aerden, K.; De Moortel, D.; Vanroelen, C. Employment quality as a health determinant: Empirical evidence for the waged and self-employed. Work. Occup. 2021, 48, 146–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aerden, K.; Puig-Barrachina, V.; Bosmans, K.; Vanroelen, C. How does employment quality relate to health and job satisfaction in Europe? A typological approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 158, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.; Enquobahrie, D.A.; Peckham, T.; Seixas, N.; Hajat, A. Retrospective cohort study of the association between maternal employment precarity and infant low birth weight in women in the USA. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e029584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, S.B.; Eisenberg-Guyot, J.; Oddo, V.M.; Peckham, T.; Jacoby, D.; Hajat, A. Beyond Hours Worked and Dollars Earned: Multidimensional EQ, Retirement Trajectories and Health in Later Life. Work. Aging Retire. 2021, 8, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg-Guyot, J.; Peckham, T.; Andrea, S.B.; Oddo, V.; Seixas, N.; Hajat, A. Life-course trajectories of employment quality and health in the US: A multichannel sequence analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, T.; Flaherty, B.; Hajat, A.; Fujishiro, K.; Jacoby, D.; Seixas, N. What Does Non-standard Employment Look Like in the United States? An Empirical Typology of Employment Quality. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, V.M.; Zhuang, C.C.; Andrea, S.B.; Eisenberg-Guyot, J.; Peckham, T.; Jacoby, D.; Hajat, A. Changes in precarious employment in the United States: A longitudinal analysis. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Healthy People 2030 Social Determinants of Health Literature Summaries: Employment. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/employment (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- NIOSH. Healthy Work Design and Well-Being Program; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Insitute for Occupational Safety and Health, Eds.; DHHS (NIOSH) Publication: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH Strategic Plan: FYs 2019–2024; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Edmonds, A.T.; Sears, J.M.; O’Connor, A.; Peckham, T. The role of nonstandard and precarious jobs in the well-being of disabled workers during workforce reintegration. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, S.B.; Eisenberg-Guyot, J.; Peckham, T.; Oddo, V.M.; Hajat, A. Intersectional trends in employment quality in older adults in the United States. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.J.; Henly, J.R.; Kim, J. Precarious work schedules as a source of economic insecurity and institutional distrust. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 218–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckfield, J.; Krieger, N. Epi + demos + cracy: Linking Political Systems and Priorities to the Magnitude of Health Inequities—Evidence, Gaps, and a Research Agenda. Epidemiol. Rev. 2009, 31, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, P.; Brown, T.H.; King, B. Structural intersectionality as a new direction for health disparities research. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, W.; Ferrarini, T.; Englund, S. Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Soc. Politics 2013, 20, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, K.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Winkler, M. Poor-quality employment and health: How a welfare regime typology with a gender lens Illuminates a different work-health relationship for men and women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 291, 114484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, F.J. Habit, custom, and power: A multi-level theory of population health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 80, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipscomb, H.J.; Loomis, D.; McDonald, M.A.; Argue, R.A.; Wing, S. A conceptual model of work and health disparities in the United States. Int. J. Health Serv. 2006, 36, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntaner, C.; Chung, H.; Solar, O.; Santana, V.; Castedo, A.; Benach, J.; Network, E. A macro-level model of employment relations and health inequalities. Int. J. Health Serv. 2010, 40, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnall, P.L.; Dobson, M.; Landsbergis, P. Globalization, Work, and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Health Serv. 2016, 46, 656–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.K. Reconceptualizing the nature and health consequences of work-related insecurity for the new economy: The decline of workers’ power in the flexibility regime. Int. J. Health Serv. 2004, 34, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivens, J.; Mishel, L.; Schmitt, J. It’s Not Just Monopoly and Monopsony: How Market Power Has Affected American Wages; Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg, N. At What Cost: Modern Capitalism and the Future of Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, C.E.; Gaydos, M.; Monforton, C.; Slatin, C.; Borkowski, L.; Dooley, P.; Liebman, A.; Rosenberg, E.; Shor, G.; Keifer, M. Effects of social, economic, and labor policies on occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.; Richmond, T.; Shields, J. Structuring neoliberal governance: The nonprofit sector, emerging new modes of control and the marketisation of service delivery. Policy Soc. 2005, 24, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzo, F. Tactical evaluations: Everyday neoliberalism in academia. J. Sociol. 2018, 54, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentikelenis, A.; Rochford, C. Power asymmetries in global governance for health: A conceptual framework for analyzing the political-economic determinants of health inequities. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Véron, N. Too Big to Fail: The Transatlantic Debate; Working Paper Series; Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Reynolds, J.; Marsden, P.V. Externalizing employment: Flexible staffing arrangements in US organizations. Soc. Sci. Res. 2003, 32, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse, S. Why a union victory at a single Starbucks is a good sign for the labor movement. The Los Angeles Times, 13 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, G.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Peters, S.E.; Sabbath, E.L.; Kelly, E.L.; Wagner, G.R. The future of research on work, safety, health and wellbeing: A guiding conceptual framework. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 269, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgeway, C.L. The social construction of status value: Gender and other nominal characteristics. Soc. Forces 1991, 70, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L. Status construction theory. In Contemporary Social Psychological Theories, 2nd ed.; Burke, P.J., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 315–371. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Serna, J.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Artazcoz, L.; Moen, B.E.; Benavides, F.G. Gender inequalities in occupational health related to the unequal distribution of working and employment conditions: A systematic review. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.-A.S.; Li, Y.; McConnell, D.S.; McCullagh, M.C.; Seng, J.S. Stressors, allostatic load, and health outcomes among women hotel housekeepers: A pilot study. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2019, 16, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levanon, A.; England, P.; Allison, P. Occupational feminization and pay: Assessing causal dynamics using 1950–2000 US census data. Soc. Forces 2009, 88, 865–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Bartley, M.; Dundas, R.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Mitchell, R.; Popham, F.; Walsh, D.; Wami, W. Theorising social class and its application to the study of health inequalities. SSM-Popul. Health 2019, 7, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikemo, T.A.; Bambra, C. The welfare state: A glossary for public health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedhar, A.; Gotal, A. Behind low vaccination rates lurks a more profound social weakness. The New York Times, 3 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc Ngo, C.; Di Tommaso, M.R.; Tassinari, M.; Dockerty, J.M. The future of work: Conceptual considerations and a new analytical approach for the political economy. Rev. Political Econ. 2021, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.M.; Buffel, V. Organized Labor and Depression in Europe: Making Power Explicit in the Political Economy of Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2020, 61, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Tarafa, G.; Delclos, C.; Muntaner, C. What should we know about precarious employment and health in 2025? framing the agenda for the next decade of research. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewchuk, W. Precarious jobs: Where are they, and how do they affect well-being? Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2017, 28, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsthoorn, M. Measuring precarious employment: A proposal for two indicators of precarious employment based on set-theory and tested with Dutch labor market-data. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreshpaj, B.; Orellana, C.; Burström, B.; Davis, L.; Hemmingsson, T.; Johansson, G.; Kjellberg, K.; Jonsson, J.; Wegman, D.H.; Bodin, T. What is precarious employment? A systematic review of definitions and operationalizations from quantitative and qualitative studies. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2020, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A.; Amable, M.; Ferrer, M.; Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Muntaner, C.; Benavides, F.G.; Benach, J. The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES): Psychometric properties of a new tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haardörfer, R. Taking quantitative data analysis out of the positivist era: Calling for theory-driven data-informed analysis. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, F.J. Population health science: Fulfilling the mission of public health. Milbank Q. 2020, 99, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 1, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.M. Health Power Resources Theory: A Relational Approach to the Study of Health Inequalities. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2021, 62, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, V.A. Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2008, 11, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Redefining institutional racism. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1985, 8, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, P. Structural sexism and health in the United States: A new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 486–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieker, P.P.; Bird, C.E. Rethinking gender differences in health: Why we need to integrate social and biological perspectives. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005, 60, S40–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C. The Political Economy of the United States and the People’s Health. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 833–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Polity: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Artazcoz, L.; Cortès, I.; Benavides, F.G.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Bartoll, X.; Vargas, H.; Borrell, C. Long working hours and health in Europe: Gender and welfare state differences in a context of economic crisis. Health Place 2016, 40, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moortel, D.; Vandenheede, H.; Vanroelen, C. Contemporary employment arrangements and mental well-being in men and women across Europe: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner, C.; Solar, O.; Vanroelen, C.; Martínez, J.M.; Vergara, M.; Santana, V.; Castedo, A.; Kim, I.-H.; Benach, J.; Network, E. Unemployment, informal work, precarious employment, child labor, slavery, and health inequalities: Pathways and mechanisms. Int. J. Health Serv. 2010, 40, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckfield, J.; Morris, K.A.; Bambra, C. How social policy contributes to the distribution of population health: The case of gender health equity. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.A.; Beckfield, J.; Bambra, C. Who benefits from social investment? The gendered effects of family and employment policies on cardiovascular disease in Europe. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.R.; Hill, H.D.; Mooney, S.J.; Rivara, F.P.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A. State Earned Income Tax Credits and Depression and Alcohol Misuse Among Women with Children. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Revisiting the Corporate and Commercial Determinants of Health. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1167–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mialon, M.; Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G. A proposed approach to systematically identify and monitor the corporate political activity of the food industry with respect to public health using publicly available information. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Cameron, L.; Garrett, L. Alternative work arrangements: Two images of the new world of work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Vaughan, R.D. Moving Beyond the Cause Constraint: A Public Health of Consequence, May 2018. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 602–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glymour, M.M.; Hamad, R. Causal thinking as a critical tool for eliminating social inequalities in health. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. The lost art of discovery: The case for inductive methods in occupational health science and the broader organizational sciences. Occup. Health Sci. 2017, 1, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 30, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sociopolitical factors | Labor laws and enforcement, workers’ rights and social protections, prevailing business practices, science and technology, and political rhetoric/public discourse [39,40,41,52]. They exist everywhere but their forms and functions are specific to place and time. Together with labor market contexts, they set the grade of the tilted playing field on which the arrangements and conditions of employment exist. |

| Labor market context | The particulars of time and place-specific unemployment rates, informal employment rates, and demands for goods and services that are interrelated to sociopolitical factors and form the worker–employer reality where arrangements and conditions of employment exist. |

| Political power | Power used to influence society through the political process, such as employers’ lobbying and political contributions, and workers’ voting and community activism [40]. Political power influences the grade of the slope of the employment playing field. |

| Power resources [20] | Tools, or sources of power, that the employer and workers each can use to try to achieve their respective wants. Workers can use their human capital (i.e., education, skills) and collective organization. Employers can use hiring and firing authority, job simplification, flexible staffing practices, non-union positions, relocation, and outsourcing. These are sources of potential power and may not be actually exercised (see “power resources model”). |

| Employment quality | The result of the power dynamics that shapes arrangements and conditions of employment; a package consisting of employment stability, rights for workers and their ability to exercise them, and the terms of employment [4,5,10]. The package exists on a conceptual spectrum of better and poorer configurations of these characteristics. From the employer’s perspective, the package represents labor cost and worker productivity [50]. |

| Power resources model [20] | Describes the calculations and processes parties use in attempting to achieve their respective wants; results in exchange or conflict if power resources are relatively balanced, and exploitation if one party’s power resources outweigh the other’s. Power may not have to be actively used in a given circumstance if all parties understand the imbalance [20,38]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fujishiro, K.; Ahonen, E.Q.; Winkler, M. Investigating Employment Quality for Population Health and Health Equity: A Perspective of Power. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169991

Fujishiro K, Ahonen EQ, Winkler M. Investigating Employment Quality for Population Health and Health Equity: A Perspective of Power. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169991

Chicago/Turabian StyleFujishiro, Kaori, Emily Q. Ahonen, and Megan Winkler. 2022. "Investigating Employment Quality for Population Health and Health Equity: A Perspective of Power" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169991

APA StyleFujishiro, K., Ahonen, E. Q., & Winkler, M. (2022). Investigating Employment Quality for Population Health and Health Equity: A Perspective of Power. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169991