Sedentary Behavior Counseling Received from Healthcare Professionals: An Exploratory Analysis in Adults at Primary Health Care in Brazil

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Study Site, and Ethical Aspects

2.2. Sample Size, Number of Participants, and Power

2.3. Selection of Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Outcome Variable: Sedentary Behavior Counseling

2.6. Independent Variables

2.6.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.6.2. Health Conditions

2.6.3. Access to Health Services

2.6.4. Health Risks Behaviors

Leisure-Time Physical Activity

Sedentary Behavior

2.7. Data Quality Control

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Owen, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Eakin, E.E.; Gardiner, P.A.; Tremblay, M.S.; Sallis, J.F. Adults’ sedentary behavior: Determinants and interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Hagströmer, M.; Craig, C.L.; Bull, F.C.; Pratt, M.; Venugopal, K.; Chau, J.; Sjöström, M. IPS Group. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting: A 20-country comparison using the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ). Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.; Atkin, A.J.; Starr, L.; Hall, A.; Wolfenden, L.; Sutherland, R.; Wiggers, J.; Ramirez, A.; Hallal, P.; Pratt, M.; et al. Worldwide surveillance of self-reported sitting time: A scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, L.F.M.; Sá, T.H.; Mielke, G.I.; Viscondi, J.Y.K.; Rey-López, J.P.; Garcia, L.M.T. All-cause mortality attributable to sitting time: Analysis of 54 countries worldwide. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Le, L.K.D.; Ananthapavan, J.; Gao, L.; Dunstan, D.W.; Moodie, M. Economics of sedentary behaviour: A systematic review of cost of illness, cost-effectiveness, and return on investment studies. Prev. Med. 2022, 156, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.L.M.; Werneck, A.O.; Silva, D.R.; Kovalskys, I.; Gómez, G.; Rigotti, A.; Sanabria, L.Y.C.; García, M.C.Y.; Pareja, R.G.; Herrera-Cuenca, M.; et al. Socio-demographic correlates of total and domain-specific sedentary behavior in Latin America: A population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; Silva, I.C.M.; Owen, N.; Hallal, P.C. Brazilian adults’ sedentary behaviors by life domain: Population-based study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Brown, W.J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.E.; Lee, I.M. Do the associations of sedentary behaviour with cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer mortality differ by physical activity level? A systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis of data from 850 060 participants. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyfault, J.P.; Du, M.; Kraus, W.E.; Levine, J.A.; Booth, F.W. Physiology of sedentary behavior and its relationship to health outcomes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1301–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Brown, W.J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M. Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committe; Lancet Sedentary Behaviour Working Group Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. 2018. Geneva. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Milton, K.; Cavill, N.; Chalkley, A.; Foster, C.; Gomersall, S.; Hagstromer, M.; Kelly, P.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Mair, J.; McLaughlin, M.; et al. Eight investments that work for physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2021, 18, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manini, T.M.; Carr, L.J.; King, A.C.; Marshall, S.; Robinson, T.N.; Rejeski, W.J. Interventions to reduce sedentary behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1306–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, N.E.; Wilson, J.J.; McMullan, I.I.; Caserotti, P.; Giné-Garriga, M.; Wirth, K.; Coll-Planas, L.; Alias, S.B.; Roqué, M.; Deidda, M.; et al. The effectiveness and complexity of interventions targeting sedentary behaviour across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.W.; Dogra, S.; Carter, S.E.; Owen, N. Sit less and move more for cardiovascular health: Emerging insights and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Faulkner, G.; Ciliska, D.; Hicks, A. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of physical activity counselling in primary care: A realist systematic review. Pat. Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, E.A.; Evans, C.V.; Rushkin, M.C.; Redmond, N.; Lin, J.S. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 324, 2076–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, S.; Copeland, J.L.; Altenburg, T.M.; Heyland, D.K.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D.W. Start with reducing sedentary behavior: A stepwise approach to physical activity counseling in clinical practice. Patient. Educ. Couns. 2021, 105, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paim, J.; Travassos, C.; Almeida, C.; Bahia, L.; MacInko, J. The Brazilian health system: History, advances, and challenges. Lancet 2011, 377, 1778–17797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. National Health Survey 2019. Primary Health Care and Anthropometric Information. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101748.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Gomes, G.A.O.; Kokubun, E.; Mieke, G.I.; Ramos, L.R.; Pratt, M.; Parra, D.C.; Simões, E.; Florindo, A.A.; Bracco, M.; Cruz, D.; et al. Characteristics of physical activity programs in the Brazilian primary health care system. Cad. Saúde Pública 2014, 30, 2155–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuval, K.; DiPietro, L.; Skinner, C.S.; Barlow, C.E.; Morrow, J.; Goldsteen, R.; Kohl, H.W., 3rd. “Sedentary behaviour counselling”: The next step in lifestyle counselling in primary care; Pilot findings from the Rapid Assessment Disuse Index (RADI) study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, A.; Vuillemin, A.; Thornton, J.S.; Theisen, D.; Stranges, S.; Ward, M. Physical activity promotion in primary care: A utopian quest? Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.T.; Santos, L.P.; Rodriguez-Añez, C.R.; Fermino, R.C. Logic model of “Cidade Ativa, Cidade Saudável Program” in São José dos Pinhais, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Física Saúde 2021, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.P.; Silva, A.T.; Rech, C.R.; Fermino, R.C. Physical activity counseling among adults in Primary Health Care centers in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansournia, M.A.; Collins, G.S.; Nielsen, R.O.; Nazemipour, M.; Jewell, N.P.; Altman, D.G.; Campbell, M.J. A CHecklist for statistical Assessment of Medical Papers (the CHAMP statement): Explanation and elaboration. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häfele, V.; Siqueira, F. Physical activity counseling and change of behavior in Basic Health Units. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Física Saúde 2016, 21, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J. Public Health 2005, 27, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, S.Q.; Souza, J.H.; Araújo, P.A.B.; Rech, C.R. Prevalence of physical activity counseling in primary health care: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Física Saúde 2019, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, A.A.; Owen, N.; Neuhaus, M.; Dunstan, D.W. Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L.C.; Heitkemper, M.M.L.; Chiang, S.L.; Tzeng, W.C.; Lee, M.S.; Hung, Y.J.; Lin, C.H. Motivational counseling to reduce sedentary behaviors and depressive symptoms and improve health-related quality of life among women with metabolic syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Synthesis of Social Indicators: An Analysis of the Living Conditions of the Brazilian Population. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/multidominio/genero/9221-sintese-de-indicadores-sociais.html?=&t=resultados (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- ABEP. Brazilian Association of Research Companies. Brazil Economic Classification Criteria. 2019. Available online: http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Brasil. Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Health Surveillance. Department of Health Analysis and Surveillance of Noncommunicable Diseases. VIGITEL Brasil 2021: Surveillance System for Risk and Protective Factors for Chronic Diseases by Telephone Survey. Brasilia-DF. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/publicacoes-svs/vigitel/relatorio-vigitel-2020-original.pdf/view (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Matsudo, S.; Araujo, T.; Matsudo, V.; Andrade, D.; Andrade, E.; Oliveira, L.C.; Braggion, G. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Study of validity and reliability in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Física Saúde 2001, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, G.I.; Silva, I.C.M.; Gomersall, S.R.; Owen, N.; Hallal, P.C. Reliability of a multi-domain sedentary behaviour questionnaire and comparability to an overall sitting time estimate. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, A.J.D.; Hirakata, V.N. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Huttly, S.R.; Fuchs, S.C.; Olinto, M.T. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierre, D.; Coelho-Ravagnani, C.; Tenório, M.C.; Andrade, D.R.; Autran, R.; Barros, M.V.G.; Benedetti, T.R.B.; Cavalcante, F.V.S.A.; Cyrino, E.S.; Dumith, S.C.; et al. Physical activity guidelines for the Brazilian population: Recommendations report. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Pedisic, Z.; Jurakic, D.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Parker, A. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour counselling: Attitudes and practices of mental health professionals. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Cassenote, A.; Guerra, A.; Guilloux, A.G.A.; Brandão, A.P.D.; Miotto, B.A.; Almeida, C.J.; Gomes, J.O.; Miotto, R.A. Medical Demographics in Brazil 2020. Available online: https://www.fm.usp.br/fmusp/conteudo/DemografiaMedica2020_9DEZ.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- ACSM. American College of Sports Medicine. Reducing Sedentary Behaviors: Sit Less and Move More. American College of Sports Medicine. Available online: https://www.acsm.org/docs/default-source/files-for-resource-library/reducing-sedentary-behaviors-sit-less-and-move-more.pdf?sfvrsn=4da95909_2 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Santos, L.P. Physical Activity Counseling Received for Adults at Public Health Clinics. [Curitiba, Brazil]: Federal University of Technological-Paraná; 2020. Available online: http://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/5039 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

| Variable | Categories | n | % | 95% CI | Mean ± S. D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex | Male | 235 | 30.2 | 27.0–33.5 | – |

| Female | 544 | 69.8 | 66.5–73.0 | ||

| Age group (yrs) | 18–39 | 346 | 45.2 | 41.7–48.7 | 43.7 ± 16.1 |

| 40–59 | 283 | 36.9 | 33.6–40.4 | ||

| ≥60 | 137 | 17.9 | 15.3–20.8 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 280 | 36.0 | 32.7–39.5 | – |

| Not single | 497 | 64.0 | 60.5–67.3 | ||

| Skin color | White | 566 | 73.0 | 69.8–76.0 | – |

| Non-white | 209 | 27.0 | 24.0–30.2 | ||

| Economic level | Low | 555 | 71.2 | 68.0–74.3 | – |

| High | 224 | 28.8 | 25.7–32.0 | ||

| Health conditions | |||||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | ≤24.9 | 242 | 31.5 | 28.3–34.8 | 27.9 ± 5.2 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 294 | 38.2 | 34.9–41.7 | ||

| ≥30.0 | 233 | 30.3 | 27.2–33.6 | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 0 | 334 | 42.9 | 39.4–46.4 | 1.2 ± 1.4 |

| 1–2 | 311 | 39.9 | 36.5–43.4 | ||

| ≥3 | 134 | 17.2 | 14.7–20.0 | ||

| Number of prescribed medications | 0 | 387 | 49.7 | 46.2–53.2 | 2.4 ± 2.6 |

| 1–2 | 223 | 28.6 | 25.6–31.9 | ||

| ≥3 | 169 | 21.7 | 18.9–24.7 | ||

| Access to health services | |||||

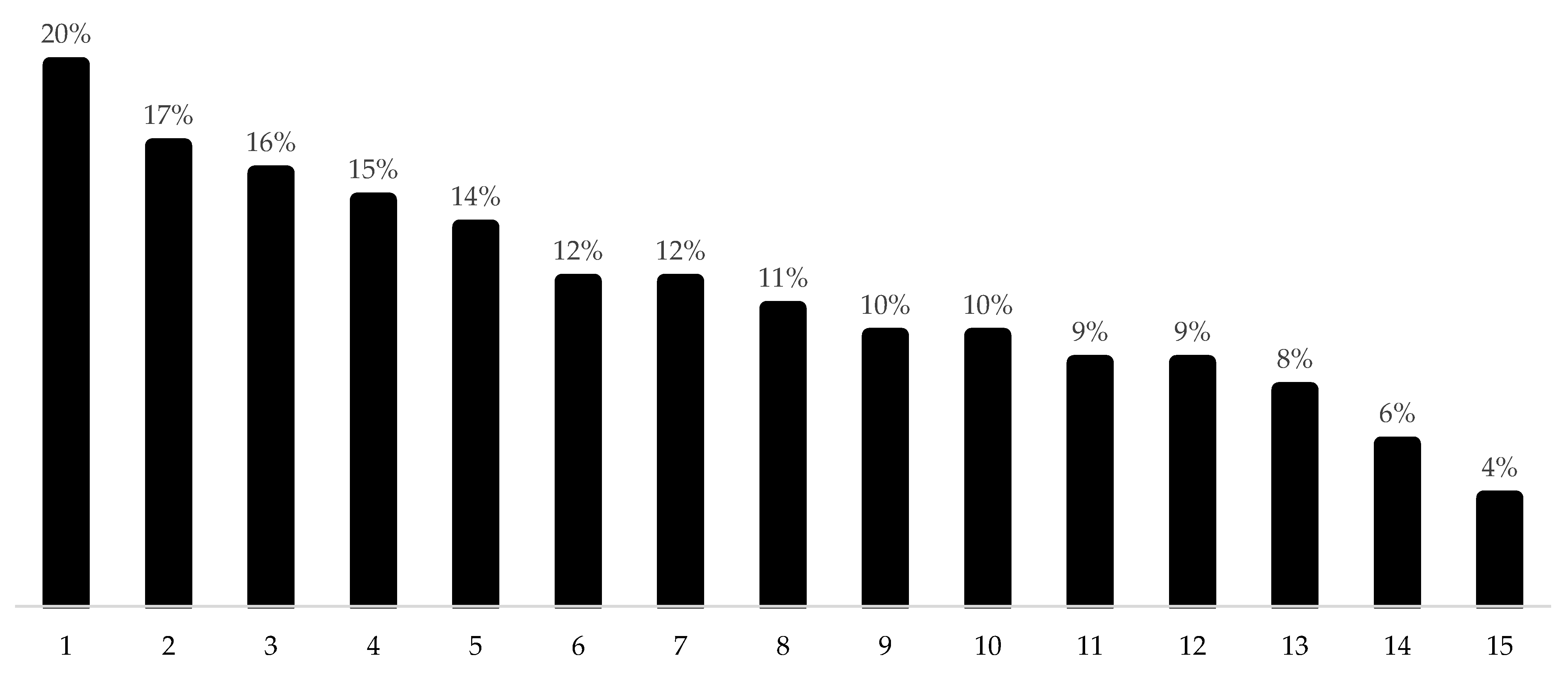

| Frequency of visits to Basic Health Unit in the last year | 0–2 | 291 | 37.4 | 34.0–40.8 | 5.5 ± 6.0 |

| 3–6 | 299 | 38.4 | 35.0–41.8 | ||

| ≥7 | 189 | 24.3 | 21.4–27.4 | ||

| Health risks behavior | |||||

| Leisure-time physical activity | |||||

| Walking (min/wk) | 0–9 | 567 | 72.8 | 69.6–75.8 | 50.2 ± 113.8 |

| 10–149 | 108 | 13.9 | 11.6–16.5 | ||

| ≥150 | 104 | 13.4 | 11.1–15.9 | ||

| MVPA (min/wk) | 0–9 | 626 | 80.4 | 77.4–83.0 | 15.2 ± 63.8 |

| 10–149 | 55 | 7.1 | 5.5–9.1 | ||

| ≥150 | 98 | 12.5 | 10.4–15.1 | ||

| Sedentary behavior | |||||

| Sitting time (h/day)—quartiles * | 0–1.7 | 193 | 24.8 | 21.9–27.9 | 4.3 ± 3.5 |

| 1.8–3.3 | 192 | 24.6 | 21.7–27.8 | ||

| 3.4–6.1 | 197 | 25.3 | 22.4–28.5 | ||

| ≥6.2 (4th quartile) | 197 | 25.3 | 22.4–28.5 | ||

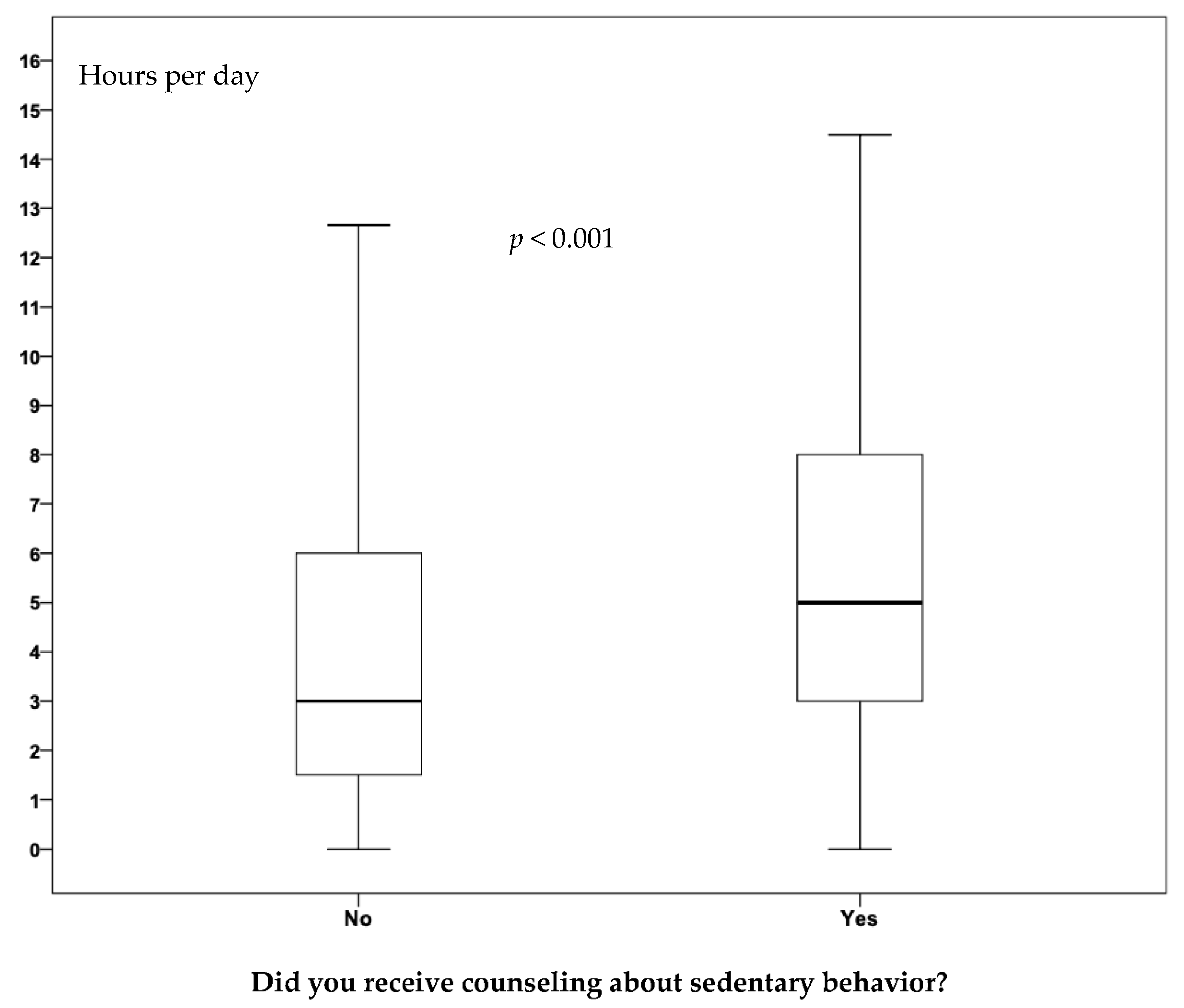

| Did you receive counseling about sedentary behavior? | No | 684 | 87.8 | 85.3–89.9 | – |

| Yes | 95 | 12.2 | 10.1–14.7 |

| Hours Per Day | Mean | S. D. | 95% CI | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watching TV | 1.88 | 2.03 | 1.73–2.02 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Working | 1.14 | 2.44 | 0.97–1.32 | 0.04 | 1.00 |

| Commuting | 0.65 | 0.99 | 0.58–0.72 | 0.33 | 1.00 |

| Using computer at home | 0.37 | 1.05 | 0.30–0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Studying | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.18–0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 4.26 | 3.47 | 4.02–4.51 | 3.25 | 4.30 |

| No (n = 684, 87.8%) | Yes (n = 95, 12.2%) | Sig.* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours Per Day | Mean | S. D. | 95% CI | Median | IQR | Mean | S. D. | 95% CI | Median | IQR | |

| Watching TV | 1.83 | 2.02 | 1.67–1.98 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.25 | 2.07 | 1.82–2.68 | 2.00 | 2.20 | 0.025 |

| Working | 1.02 | 2.28 | 0.85–1.19 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 2.05 | 3.21 | 1.39–2.71 | 0.00 | 3.50 | 0.009 |

| Commuting | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.57–0.71 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 1.17 | 0.47–0.95 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.532 |

| Using computer at home | 0.37 | 1.04 | 0.29–0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 | 1.16 | 0.13–0.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.832 |

| Studying | 0.24 | 0.89 | 0.18–0.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.59 | −0.03–0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.118 |

| Total | 4.10 | 3.40 | 3.84–4.35 | 3.00 | 4.50 | 5.48 | 3.69 | 4.72–6.23 | 5.00 | 5.00 | <0.001 |

| Prevalence of SB Counseling (%) | Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 95% CI | p * | PR | 95% CI | p * | |||

| Level 1—Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Sex | Male | 8.5 | 1 | 1 a | ||||

| Female | 13.8 | 1.62 | 1.01–2.59 | 0.044 | 1.77 | 1.10–2.83 | 0.017 | |

| Age group (yrs) | 18–39 | 10.3 | 1 | 1 b | ||||

| 40–59 | 12.1 | 1.16 | 0.75–1.80 | 0.491 | 1.22 | 0.78–1.89 | 0.370 | |

| ≥60 | 17.0 | 1.65 | 1.02–2.65 | 0.041 | 1.84 | 1.14–2.98 | 0.013 | |

| Marital status | Single | 11.1 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Not single | 12.9 | 1.16 | 0.77–1.74 | 0.463 | – | – | – | |

| Skin color | White | 12.2 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Non–white | 12.4 | 1.02 | 0.70–1.56 | 0.925 | – | – | – | |

| Economic level | Low | 12.1 | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| High | 12.5 | 1.04 | 0.69–1.57 | 0.869 | – | – | – | |

| Level 2—Health conditions | ||||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | <24.9 kg/m2 | 7.4 | 1 | 1 c | ||||

| 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 | 8.8 | 1.19 | 0.67–2.12 | 0.556 | 1.30 | 0.62–2.73 | 0.482 | |

| ≥30.0 kg/m2 | 21.5 | 2.89 | 1.74–4.80 | <0.001 | 2.60 | 1.31–5.17 | 0.006 | |

| Number of chronic diseases | 0 | 7.5 | 1 | 1 d | ||||

| 1–2 | 15.4 | 2.06 | 1.30–3.26 | 0.002 | 1.28 | 0.64–2.55 | 0.490 | |

| ≥3 | 16.4 | 2.19 | 1.28–3.75 | 0.004 | 0.86 | 0.38–1.93 | 0.706 | |

| Number of prescribed medications | 0 | 7.2 | 1 | 1 e | ||||

| 1–2 | 14.8 | 2.05 | 1.27–3.29 | 0.003 | 1.89 | 0.99–3.59 | 0.053 | |

| ≥3 | 20.1 | 2.78 | 1.74–4.43 | <0.001 | 2.21 | 1.06–4.59 | 0.035 | |

| Level 3—Access to health services | ||||||||

| Frequency of visits to Basic Health Unit on the last year (times) | 0–2 | 9.6 | 1 | 1 f | ||||

| 3–6 | 11.7 | 1.22 | 0.76–1.95 | 0.414 | 0.98 | 0.61–1.55 | 0.916 | |

| ≥7 | 16.9 | 1.76 | 1.10–2.82 | 0.019 | 1.41 | 0.87–2.26 | 0.162 | |

| Level 4–Health risks behaviors | ||||||||

| Walking (min/wk) | 0–9 | 10.4 | 1 | 1 g | ||||

| 10–149 | 16.7 | 1.60 | 0.99–2.60 | 0.057 | 1.36 | 0.83–2.21 | 0.222 | |

| ≥150 | 17.3 | 1.66 | 1.03–2.70 | 0.040 | 1.43 | 0.90–2.29 | 0.132 | |

| MVPA (min/wk) | 0–9 | 12.3 | 1 | |||||

| 10–149 | 9.1 | 0.74 | 0.31–1.75 | 0.492 | – | – | – | |

| ≥150 | 13.3 | 1.08 | 0.62–1.87 | 0.787 | – | – | – | |

| Sedentary behavior (sitting time in h/day)—(quartiles) | 0–1.7 | 6.2 | 1 | 1 h | ||||

| 1.8–3.3 | 12.0 | 1.94 | 0.99–3.76 | 0.055 | 2.03 | 1.03–4.01 | 0.041 | |

| 3.4–6.1 | 10.7 | 1.73 | 0.87–3.39 | 0.121 | 2.28 | 1.17–4.43 | 0.015 | |

| ≥6.2 (4th quartile) | 19.8 | 3.19 | 1.72–5.89 | <0.001 | 3.44 | 1.88–6.31 | <0.001 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Snége, A.; Silva, A.A.d.P.d.; Mielke, G.I.; Rech, C.R.; Siqueira, F.C.V.; Rodriguez-Añez, C.R.; Fermino, R.C. Sedentary Behavior Counseling Received from Healthcare Professionals: An Exploratory Analysis in Adults at Primary Health Care in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169963

Snége A, Silva AAdPd, Mielke GI, Rech CR, Siqueira FCV, Rodriguez-Añez CR, Fermino RC. Sedentary Behavior Counseling Received from Healthcare Professionals: An Exploratory Analysis in Adults at Primary Health Care in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169963

Chicago/Turabian StyleSnége, André, Alexandre Augusto de Paula da Silva, Grégore Iven Mielke, Cassiano Ricardo Rech, Fernando Carlos Vinholes Siqueira, Ciro Romelio Rodriguez-Añez, and Rogério César Fermino. 2022. "Sedentary Behavior Counseling Received from Healthcare Professionals: An Exploratory Analysis in Adults at Primary Health Care in Brazil" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169963

APA StyleSnége, A., Silva, A. A. d. P. d., Mielke, G. I., Rech, C. R., Siqueira, F. C. V., Rodriguez-Añez, C. R., & Fermino, R. C. (2022). Sedentary Behavior Counseling Received from Healthcare Professionals: An Exploratory Analysis in Adults at Primary Health Care in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169963