Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

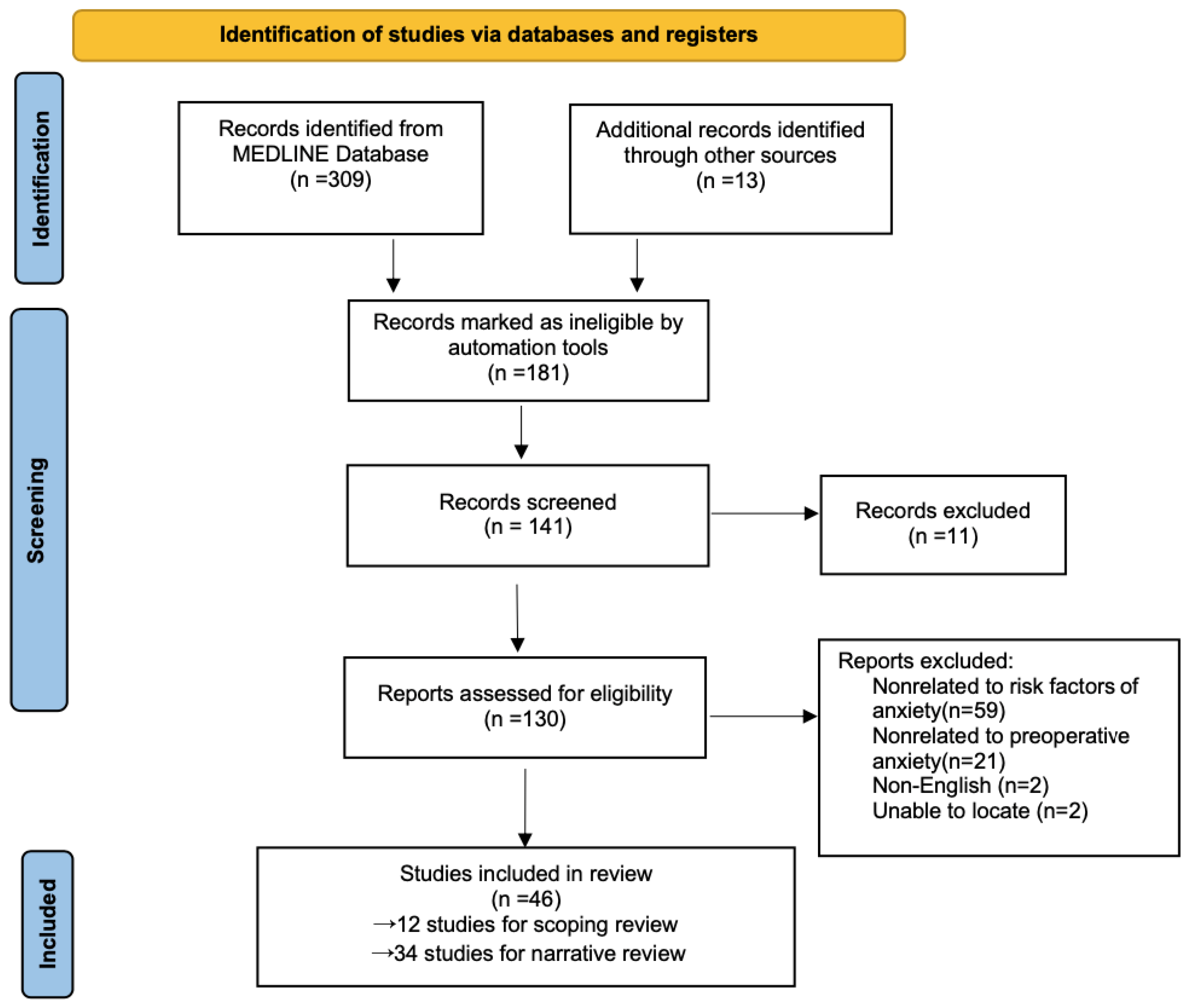

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Children’s Factors

3.1.1. Age Factor

3.1.2. Temperament Factor

3.1.3. Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment History Factors

3.1.4. Other Factors

| First Author, Year | Type of Surgery, Participants | Type of Study | Age Group, Incidence of Preoperative Anxiety | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liang Y, 2021 [7] | Elective surgery, 220 | Cross-sectional survey study | 2 to 7, 67.6% | Unschooled children, medical staff’s attention, the degree of cooperation when puncturing the venous needle |

| Chen A, 2021 [31] | Ophthalmic surgery, 183 | Retrospective analysis | 3 to 7, not described | Being the only child, lower body weight, parental educational level |

| Getahun AB, 2020 [15] | Elective surgery, 173 | Cross-sectional observational study | 2 to 12, 75.44% | Younger age, previous surgery and anesthesia, surgical setting, parental anxiety |

| Arze S, 2020 [20] | Elective outpatient or inpatient surgery, 204 | Cohort study | 2 to 12, 41.7% | Language barrier, parental anxiety, previous negative surgical experience |

| Charana A, 2018 [16] | Elective surgery, 128 | Observational study | 1 to 14, not described | High parental anxiety, age, being the only child, living in rural areas, education level, previous hospitalization |

| Mamtora PH, 2018 [18] | Outpatient adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy surgeries, 294 | Cohort study | 2 to 15, not described | Younger, less sociable children, language barriers |

| Malik R, 2018 [22] | Elective surgery, 60 | Prospective observational study | 7 to 12, 48% | Parental anxiety, socioeconomic background |

| Moura LA, 2016 [13] | Outpatient surgery, 210 | Cross-sectional survey study | 5 to 12, 42% | Age, socioeconomic status |

| Cui X, 2016 [17] | (ENT) plastic or ophthalmological surgeries, 102 | Observational study | 2 to 12, not described | Preschool children, parental anxiety |

| Kim JE, 2012 [14] | Elective surgery, 455 | Prospective, observational study | 2 to 12, 52.1% | Young age, long waiting times |

| Fortier MA, 2010 [21] | Outpatient tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, 261 | Prospective observational study | 2 to 12, not described | Low child sociability, high parent anxiety |

| Davidson AJ, 2006 [19] | Any general anesthesia surgery, 1250 | Prospective cohort study | 3 to 12, 50.2% | healthcare attendances, longer duration of procedure, having more |

3.2. Parental Factors

3.3. Surgical Factors

3.3.1. Environmental Factors

3.3.2. Operation Type

3.3.3. Preoperative Waiting Area Environment and Waiting Time

3.4. Anesthesia Factors

3.5. Other Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Number Of Surgeries in Chinese Healthcare Institutions 2018. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/ (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Li, X.R.; Zhang, W.H.; Williams, J.P.; Li, T.; Yuan, J.H.; Du, Y.; Liu, J.D.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. A multicenter survey of perioperative anxiety in China: Pre- and postoperative associations. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Jung, H.K.; Lee, G.G.; Kim, H.Y.; Park, S.G.; Woo, S.C. Effect of behavioral intervention using smartphone application for preoperative anxiety in pediatric patients. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2013, 65, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassai, B.; Rabilloud, M.; Dantony, E.; Grousson, S.; Revol, O.; Malik, S.; Ginhoux, T.; Touil, N.; Chassard, D.; Neto, E.P.D.S. Introduction of a paediatric anaesthesia comic information leaflet reduced preoperative anxiety in children. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perry, J.N.; Hooper, V.D.; Masiongale, J. Reduction of Preoperative Anxiety in Pediatric Surgery Patients Using Age-Appropriate Teaching Interventions. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2012, 27, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.H.; Van Lieshout, R.J.; Schmidt, L.A.; Dobson, K.G.; Buckley, N. Systematic Review: Audiovisual Interventions for Reducing Preoperative Anxiety in Children Undergoing Elective Surgery. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, Y.; Huang, W.; Hu, X.; Jiang, M.; Liu, T.; Yue, H.; Li, X. Preoperative anxiety in children aged 2–7 years old: A cross-sectional analysis of the associated risk factors. Transl. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, J. Effects of advance exposure to an animated surgery-related picture book on preoperative anxiety and anesthesia induction in preschool children: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, Z.N.; Wang, S.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Caramico, L.A.; Hofstadter, M.B. Distress During the Induction of Anesthesia and Postoperative Behavioral Outcomes. Anesthesia Analg. 1999, 88, 1042–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, Z.N.; Sevarino, F.; Alexander, G.M.; Pincus, S.; Mayes, L.C. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated-measures design. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 49, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Moura, L.A.; Dias, I.M.; Pereira, L.V. Prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety in children aged 5-12 years 1. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2016, 24, e2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Jo, B.; Oh, H.; Choi, H.; Lee, Y. High anxiety, young age and long waits increase the need for preoperative sedatives in children. J. Int. Med. Res. 2012, 40, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Getahun, A.B.; Endalew, N.S.; Mersha, A.T.; Admass, B.A. Magnitude and Factors Associated with Preoperative Anxiety Among Pediatric Patients: Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2020, 11, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charana, A.; Tripsianis, G.; Matziou, V.; Vaos, G.; Iatrou, C.; Chloropoulou, P. Preoperative Anxiety in Greek Children and Their Parents When Presenting for Routine Surgery. Anesthesiol Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 5135203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cui, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Luo, A.; Wei, J. Parental state anxiety correlates with preoperative anxiety in Chinese preschool children. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2016, 52, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamtora, P.H.; Kain, Z.N.; Stevenson, R.S.; Golianu, B.; Zuk, J.; Gold, J.I.; Fortier, M.A. An evaluation of preoperative anxiety in Spanish-speaking and Latino children in the United States. Pediatr. Anesth. 2018, 28, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.J.; Shrivastava, P.P.; Jamsen, K.; Huang, G.H.; Czarnecki, C.; Gibson, M.A.; Stewart, S.A.; Stargatt, R. Risk factors for anxiety at induction of anesthesia in children: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Anesth. 2006, 16, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arze, S.; Lagos, C.; Ibacache, M.; Zamora, M.; González, A. Incidence and risk factors of preoperative anxiety in Spanish-speaking children living in a Spanish-speaking country. Pediatr. Anesth. 2020, 30, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortier, M.A.; Del Rosario, A.M.; Martin, S.R.; Kain, Z.N. Perioperative anxiety in children. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2010, 20, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Yaddanpudi, S.; Panda, N.B.; Kohli, A.; Mathew, P.J. Predictors of Pre-operative Anxiety in Indian Children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2018, 85, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiles Sebastián, M.F.; Méndez Carrillo, F.; Ortigosa Quiles, J. Preocupaciones prequirúrgicas: Estudio empírico con población infantil y adolescente [Pre-surgical worries: An empirical study in the child and adolescent population]. An. Esp. Pediatr. 2001, 55, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kain, Z.N.; Caldwell-Andrews, A.A.; LoDolce, M.E.; Krivutza, D.M.; Wang, S.M. The peri operative behavioral stress response in children. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, A1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Farrell, M.A.; Parrish, K.; Karla, A. Preoperative anxiety in children risk factors and non-pharmacological management. Middle East J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 21, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dave, N.M. Premedication and induction of anaesthesia in paediatric patients. Indian J. Anaesth. 2019, 63, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, H.H.; Lemery, K.S.; Aksan, N.; Buss, K.A. Temperament substrates of personality development. In Temperament and Personality Development across the Life-Span; Molfese, V.J., Molfese, D.L., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, C.H.T.; Rizwan, A.; Xu, R.; Poulin, L.; Bhardwaj, V.; Van Lieshout, R.J.; Buckley, N.; Schmidt, L.A. Association of Temperament With Preoperative Anxiety in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e195614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M.A.; Martin, S.R.; Chorney, J.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Kain, Z.N. Preoperative anxiety in adolescents undergoing surgery: A pilot study. Pediatr. Anesth. 2011, 21, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.L.; Shetty, N.S.; Shetty, K.S.; Pope, H.L.; Campbell, J.R. Pediatric Dental Surgery Under General Anesthesia: Uncooperative Children. Anesthesia Prog. 2018, 65, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Sheng, H.; Xie, Z.; Shen, W.; Chen, Q.; Lin, Y.; Gan, X. Prediction of preoperative anxiety in preschool children undergoing ophthalmic surgery based on family characteristics. J. Clin. Anesth. 2021, 75, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Shafina, M.N.; Abdul Rasyid, A.; Anis Siham, Z.A.; Nor Izwah, M.K.; Jamaluddin, M. Parental perception of children’s weight status and sociodemographic factors associated with childhood obesity. Med. J. Malaysia. 2020, 75, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Utrillas-Compaired, A.; De la Torre-Escuredo, B.J.; Tebar-Martínez, A.J.; Barco, A.-D. Does preoperative psychologic distress influence pain, function, and quality of life after TKA? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2014, 472, 2457–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kain, Z.N.; Wang, S.M.; Mayes, L.C.; Krivutza, D.M.; Teague, B.A. Sensory stimuli and anxiety in children undergoing surgery: A randomized, controlled trial. Anesth. Analg. 2001, 92, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarano, F.; Corte, A.; Michielon, R.; Gava, A.; Midrio, P. Application of a non-pharmacological technique in addition to the pharmacological protocol for the management of children’s preoperative anxiety: A 10 years’ experience. La Pediatr. Med. Chir. 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorney, J.M.; Kain, Z.N. Behavioral Analysis of Children’s Response to Induction of Anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2009, 109, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrott, C.; Lee, C.-A.; Griffiths, S.; Sury, M.R.J. Perioperative experiences of anesthesia reported by children and parents. Pediatr. Anesth. 2017, 28, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylo, H.; Tarbell, S.; Stevenson, G. Mask fear in children presenting for anesthesia: Aversion, phobia, or both? Pediatr. Anesth. 2005, 15, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.L.; Wright, K.D.; Raazi, M. Randomized-controlled trial of parent-led exposure to anesthetic mask to prevent child preoperative anxiety. Étude randomisée contrôlée d’une exposition des enfants au masque anesthésique par un parent pour prévenir l’anxiété préopératoire des jeunes patients. Can. J. Anaesth. 2018, 66, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaheen, A.; Nassar, O.; Khalaf, I.; Kridli, S.A.; Jarrah, S.; Halasa, S. The effectiveness of age-appropriate pre-operative information session on the anxiety level of school-age children undergoing elective surgery in Jordan. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 24, e12634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi, J.S.; Seyedhejazi, M.; Fakhari, A.; Ghadimi, F.; Hamidi, M.; Taghizadieh, N. Preoperative Education and Decreasing Preoperative Anxiety Among Children Aged 8–10 Years Old and Their Mothers. Anesthesiol. Pain Med. 2015, 5, e25036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidson, A.; Howard, K.; Browne, W.; Habre, W.; Lopez, U. Preoperative Evaluation and Preparation, Anxiety, Awareness, and Behavior Change. In Gregory’s Pediatric Anesthesia; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 273–299. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.T.; Visram, A. Children’s preoperative anxiety and postoperative behaviour. Pediatr. Anesth. 2003, 13, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Mayer, B.; Freher, N.K.; Duncan, S.; Hout, A.V.D. Children’s internal attributions of anxiety-related physical symptoms: Age-related patterns and the role of cognitive development and anxiety sensitivity. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010, 41, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Fabes, R.A.; Reiser, M.; Cumberland, A.; Shepard, S.A.; Valiente, C.; Losoya, S.H.; Guthrie, I.K.; Thompson, M.; et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child. Dev. 2004, 75, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kayaalp, L.; Bozkurt, P.; Odabasi, G.; Dogangun, B.; Cavusoglu, P.; Bolat, N.; Bakan, M. Psychological effects of repeated general anesthesia in children. Pediatr. Anesth. 2004, 16, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.C.; Lopez, V.; Lee, T.L. Psychoeducational preparation of children for surgery: The importance of parental involvement. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 65, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, C.; Waite, P. The Dynamic Influence of Genes and Environment in the Intergenerational Transmission of Anxiety. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santapuram, P.; Stone, A.L.; Walden, R.L.; Alexander, L. Interventions for Parental Anxiety in Preparation for Pediatric Surgery: A Narrative Review. Children 2021, 8, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kain, Z.; Mayes, L. Anxiety in children during the perioperative period. In Child Development and Behavioral Pediatrics; Borestein, M., Genevro, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fronk, E.; Billick, S.B. Pre-operative Anxiety in Pediatric Surgery Patients: Multiple Case Study Analysis with Literature Review. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, W.; Xu, R.; Jia, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Bo, L. Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169828

Liu W, Xu R, Jia J, Shen Y, Li W, Bo L. Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169828

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Weiwei, Rui Xu, Ji’e Jia, Yilei Shen, Wenxian Li, and Lulong Bo. 2022. "Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169828

APA StyleLiu, W., Xu, R., Jia, J., Shen, Y., Li, W., & Bo, L. (2022). Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169828