Physical Education Classes and Responsibility: The Importance of Being Responsible in Motivational and Psychosocial Variables

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

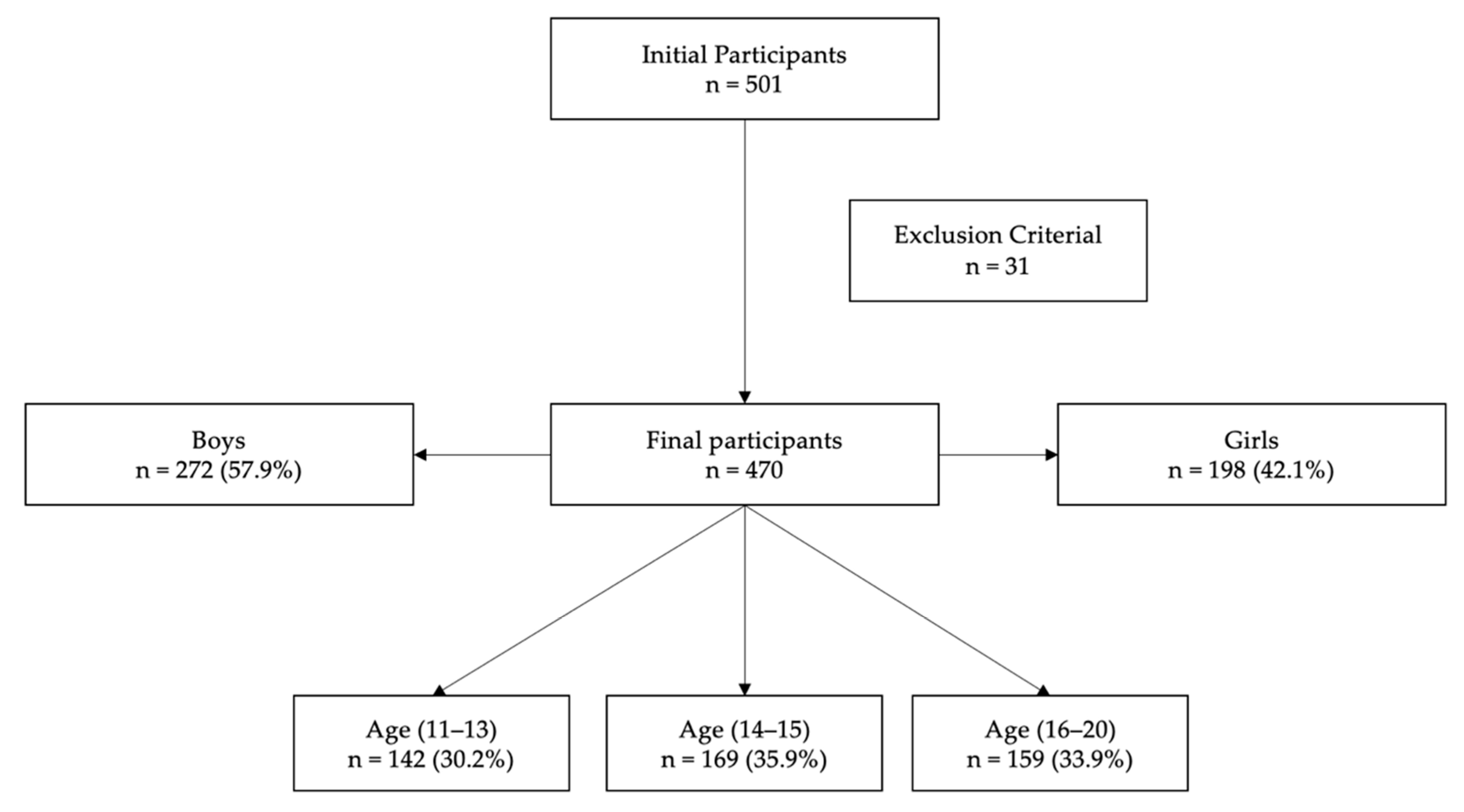

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

- Personal and Social Responsibility (PSRQ): to measure the personal and social responsibility level. The Spanish validated version of the Personal and Social Responsibility Questionnaire [36] was used with 14 items from two variables (personal and social responsibility). Participants responded on a Likert-type scale from 1 (Totally disagree) to 6 (Totally agree). The instructions were presented at the beginning of the questionnaire along with the following statement: “It is normal to behave well at times and badly at other times. We are interested in finding out how you normally behave in PE classes. There are no correct or incorrect answers. Please answer the following questions, choosing the option which bests represents your behaviour”. Reliability was of personal responsibility (Ω = 0.902) and social responsibility (Ω = 0.915).

- Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise (PNSE): to measure the satisfaction of the need for social competence, autonomy and relationships. The scale was adapted for Spanish and to the education context by Moreno et al. [37]. It is a scale with 18 items (6 from each variable). The variables were autonomy, competence and relatedness. These were preceded by the sentence “During my class…” and the answers were provided on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (False) to 6 (True). Reliability was of autonomy (Ω = 0.954), relationship (Ω = 0.956) and competence (Ω = 0.944).

- Motivation toward Education Scale (in French, EME): to measure the different types of motivation. The Spanish version of the Échelle de Motivation en Éducation [38] validated by Nuñez et al. [39] was used. The questionnaire consists of seven subscales, called intrinsic motivation to know; intrinsic motivation to accomplish; intrinsic motivation to experience sensations; identified regulation; introduced motivation; external motivation; and amotivation. The instrument is composed of 28 items preceded by the sentence “I go to school/high school because…”, with a seven-point Likert-type scale, from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree) and distributed into seven subscales, five of them containing four items and two of them containing three items. The Omega values of the different variables were: intrinsic motivation to achievement (Ω = 0.962) intrinsic motivation to experience (Ω = 0.953), intrinsic motivation to knowledge (Ω = 0.961), Identified regulation (Ω = 0.945), Introjected regulation (Ω = 0.954), external regulation (Ω = 0.949), amotivation (Ω 0.960).

- Questionnaire of School Violence (CUVE): to evaluate violence perception. It was designed by Álvarez et al. [40]. This questionnaire is composed of 41 items in eight different categories, which were adapted to primary and secondary education contexts by Álvarez et al. [41]. Answers are provided on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). In this study, the global scale was used, with a value of Omega’s coefficient of 0.885.

- Questionnaire to assess school social climate (CECSCE): to evaluate the climate perceived by the students with regard to their class, teacher and school. It was designed by Trianes et al. [42] and validated in a 12–14 years old sample. The questionnaire consists of two subscales called “Climate relative to the school” (e.g., “Students are really willing to learn”), made up of eight items, and “Climate relative to the teaching staff” (e.g., “Teachers of this school are friendly to students”), composed of six items. A five-point Likert-type scale was used, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The Omega values of the two scales were of Ω = 0.914, for the school teacher climate, and Ω = 0.90 for the school class climate.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis and Bivariate Correlations

3.2. Profile Analysis

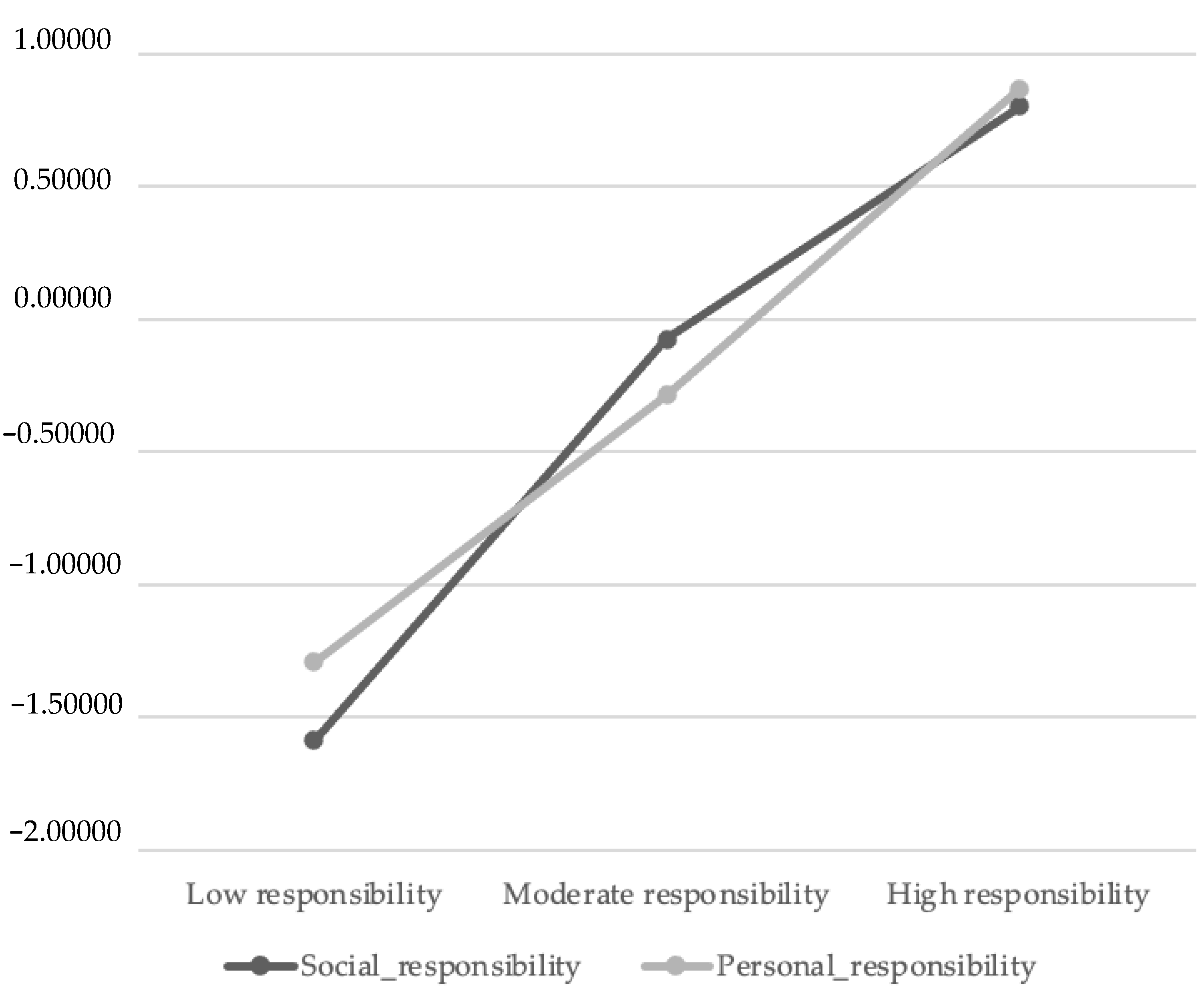

3.3. Differential Analysis of Player Profiles According to Levels of Responsibility

3.4. Differences between the Profiles According to the Sex and Age of the Participants

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griggs, G.; Fleet, M. Most People Hate Physical Education and Most Drop Out of Physical Activity: In Search of Credible Curriculum Alternatives. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forey, G.; Cheung, L. The benefits of explicit teaching of language for curriculum learning in the physical education classroom. Engl. Specif. Purp. 2019, 54, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, C. What goes around comes aroundor does it? Disrupting the cycle of traditional, sport-based physical education. Kinesiol. Rev. 2014, 3, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wright, P.; Walsh, D. Teaching personal and social responsibility. In Curricular/Instructional Models for Secondary Physical Education: Theory and Practice; Li, W., Ward, P., Sutherland, S., Eds.; Higher Education: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prat, Q.; Camerino, O.; Castañer, M.; Andueza, J.; Puigarnau, S. The personal and social responsibility model to enhance innovation in physical education. Apunts. Educ. Fis. Deporte 2019, 136, 2014-0983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleixà, T. Didáctica de la educación física: Nuevos temas, nuevos contextos. Didactae 2017, 2, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Lacárcel, J.A.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. La enseñanza de la responsabilidad en el aula de educación física escolar. Habilid. Mot. 2009, 32, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Moncada-Jiménez, J. An analysis of the responsibility of physical education students depending on the teaching methodology received. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2015, 15, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, O.; Chua, J. Science, social responsibility, and education: The experience of singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Primary and Secondary Education during Covid-19; Reimers, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 263–281. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín, M.; Carbonell, A.; Baños, C. Relaciones entre empatía, conducta prosocial, agresividad, autoeficacia y responsabilidad personal y social de los escolares. Psicothema 2011, 23, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Riciputi, S.; McDonough, M.; Ullrich-French, S. Participant Perceptions of Character Concepts in a Physical Activity-Based Positive Youth Development Program. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Implementation of a Model-Based Programme to Promote Personal and Social Responsibility and Its Effects on Motivation, Prosocial Behaviours, Violence and Classroom Climate in Primary and Secondary Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belando-Pedreño, N.; Férriz-Morel, R.; Rivas, S.; Almagro, B.; Sáenz-López, P.; Cervelló, E.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Sport commintment in adolescent soccer players. Motricidade 2015, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Pascual, C. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the personal and social responsibility questionnaire in physical education contexts. Rev. Psicol. Dep. 2011, 20, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Chen, S.; Tu, K.; Chi, L. Effect of autonomy support on self-determined motivation in elementary physical education. J. Sport Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, J.; Fernández, J. Social responsibility, basic psychological needs, intrinsic motivation. and friendship goals in physical education. Retos 2016, 32, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, M.P. School motivation and self-concept: A literature review. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 6, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Marmol, A.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Gil-Bohórquez, I.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Motivational profiles and their relationship with responsibility, school social climate and resilience in high school students. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Camerino, O.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Prat, Q.; Castañer, M. Enhancing Learner Motivation and Classroom Social Climate: A Mixed Methods Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.; Gomez-Mármol, A.; Pro, C. Scout method in primary education effects on personal and social responsibility and school violence. Athlos Int. J. Soc. Sci. Phys. Act. Game Sport 2019, 18, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; NPlenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Leo, F.M.; Mouratidis, A.; Pulido, J.; López-Gajardo, M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D. Perceived teachers’ behavior and students’ engagement in physical education: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 27, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Ntoumanis, N.; Mouratidis, A.; Katartzi, E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumanis, C.; Vlachopoulos, S. Beware of your teaching style: A school-year long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Lear. Ins. 2018, 53, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amarloo, P.; Shareh, H. Social support, responsibility, and organizational procrastination: A mediator role for basic psychological needs satisfaction. Iran. J. Psychiatry Clin. Psychol. 2018, 24, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Río, J.; Cecchini, J.A.; Merino-Barrero, J.A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Perceived Classroom Responsibility Climate Questionnaire: A new scale. Psicothema 2019, 31, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.J. Academic buoyancy and academic resilience: Exploring ‘everyday’and ‘classic’resilience in the face of academic adversity. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 34, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, D.; Rodríguez, C.; González, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Álvarez, L. La formación de los futuros docentes frente a la violencia escolar. Rev. De Psicodidact. 2010, 15, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gázquez, M.C.; Pérez-Fuentes, M. La Convivencia Escolar. Aspectos Psicológicos y Educativos; Editorial GEU: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, M.; León, B.; Gozalo, M. Perfiles de la dinámica bullying y clima de convivencia en el aula. Apunt. Psicol. 2013, 31, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Student motivation and learning in mathematics and science: A cluster analysis. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2016, 14, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernández, A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Analysis of differences according to gender in the level of physical activity, motivation, psychological needs and responsibility in Primary Education . J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2021, 16, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mármol, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Sánchez de La Cruz, E.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; González-Víllora, S. Personal and social responsibility development through sport participation in youth scholars. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2017, 17, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D. Differences between psychological aspects in Primary Education and Secondary Education. Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Responsibility, Classroom Climate, Prosocial and Antisocial behaviors and Violence. Espiral 2021, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Lara, S.; Merino-Soto, C. ¿Por qué es importante reportar los intervalos de confianza del coeficiente alfa de Cronbach? Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2015, 13, 1326–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Elosua, P.; Zumbo, B. Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema 2008, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Pascual, C. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del Cuestionario de Responsabilidad Personal y Social en contextos de educación física. Rev. De Psicol. Deport. 2011, 20, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Marzo, J.C.; Martínez-Galindo, C.; Marín, L. Validation of Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise Scale and the Behavioural Regulation in Sport Questionnaire to the Spanish context. Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2011, 7, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Blais, M.; Brière, N.M.; Pelletier, L.G. Construction et validation de l‘échelle de motivation en éducation (EME). Can. J. Behav. Sci. 1989, 21, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Núñez Alonso, J.L.; Martín-Albo, J.; Navarro Izquierdo, J.G. Validación de la versión española de la Échelle de Motivation en Éducation. Psicothema 2005, 17, 344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, L.; Álvarez-García, D.; González-Castro, P.; Nuñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.A. Evaluation of violent behaviors in secondary school. Psicothema 2006, 18, 685–695. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, D.; Pérez, J.C.; González, A.D. Questionnaires to assess school violence in primary education and secondary education: CUVE3-EP y CUVE3-ESO. Apunt. Psicol. 2013, 31, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Trianes, M.V.; Blanca, M.J.; De la Morena, L.; Infante, L.; Raya, S. A questionnaire to assess school social climate. Psicothema 2006, 18, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos-Arias, A.; Oviedo, H. Propiedades psicometricas de una escala: La consistencia interna. Rev. Salud Publica 2008, 10, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viladrich, C.; Angulo-Brunet, A.; Doval, E. A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. An. De Psicol. 2017, 33, 755–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, A. Discoring Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Learning EMEA: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bussab, W.; Mizaki, E.; Andrade, F. Introduction to Cluster Ananysis; ABE: San Pablo, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-López, M.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Abraldes, J.A. Análisis de los perfiles motivacionales y su relación con la importancia de la educación física en secundaria. Rev. Iberoam. De Diagn. Y Evaluación Psicol. 2014, 2, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Leo, F.; Amado, D.A.; Pulido-González, J.; García-Calvo, T. Análisis de los perfiles motivacionales y su relación con los comportamientos adaptativos en las clases de educación física. Rev. Lat. Psi. 2015, 47, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Croiset, G.; Galindo-Garré, F.; Ten Cate, O. Motivational profiles of medical students: Association with study effort, academic performance and exhaustion. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Inglés, C.J.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; García-Fernández, M.; Valle, A.; Castejón, J.L. Goal Orientation Profiles and Self-Concept of Secondary School Students. Rev. De Psicodidact. 2015, 20, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yli-Piipari, S.; Watt, A.; Jaakkola, T.; Liukkonen, J.; Nurmi, J. Relationships between physical education students’ motivational profiles, enjoyment, state anxiety, and self-reported physical activity. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2009, 8, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos, A.G.; Extremera, A.B.; Fuentes, J.A.; Molina, M.M. Perfiles motivacionales de apoyo a la autonomía, autodeterminación, satisfacción, importancia de la educación física e intención de práctica física en tiempo libre. CPD 2014, 14, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Rocha Seixas, L.; Gomes, A.; De Melo, F.; Ivanildo, J. Effectiveness of gamification in the engagement of students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, B.; Rodríguez, S.; Piñeiro, I.; Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.; Gayo, E.; Valle, A. Perfiles motivacionales, implicación y ansiedad ante los deberes escolares y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Estud. Investig. Psicol. Educ. 2015, 1, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, G.; Vezzani, C.; Bigozzi, L.; Pinto, G. Cluster profiles of university students’ conceptions of learning according to gender, educational level, and academic disciplines. Learn. Motiv. 2020, 70, 101628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, K.; Happell, B. Undergraduate nursing students attitude to mental health nursing: A cluster analysis approach. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3155–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, S.J. Profiles of African American college students’ educational utility and performance: A cluster analysis. J. Black. Psychol. 2000, 26, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimoglu, N.; Unaldi, I.; Samancioglu, M.; Baglibel, M. The relationship between personality traits and learning styles: A cluster analysis. Asian J. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2013, 2, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merino-Barrero, J.A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Pedreño, N.B.; Fernandez-Río, J. Impact of a sustained TPSR program on students’ responsibility, motivation, sportsmanship, and intention to be physically active. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2019, 39, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Kim, Y.; Kim, B.J. Relations of perception of responsibility to intrinsic motivation and physical activity among Korean middle school students. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2012, 115, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santurio, J.; Fernández-Río, J. Responsabilidad social, necesidades psicológicas básicas, motivación intrínseca y metas de amistad en educación física. Retos 2017, 32, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Conde-Sánchez, A.; Chen, M.Y. Applying the personal and social responsibility model-based program: Differences according to gender between basic psychological needs, motivation, life satisfaction and intention to be physically active. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shim, S.; Ryan, A. Changes in self-efficacy. Challenge avoidance and intrinsic value in response to grades: The role of achievement goals. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 73, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, M.; Ainley, J. Student engagement with science in early adolescence: The contribution of enjoyment to students’ continuing interest in learning about science. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.; Ruiz, J.; Vera, A. Prediction of autonomy support, psychological mediators and basic competences in adolescent students. Rev. Psicodidact. 2015, 20, 359–376. [Google Scholar]

- Fin, G.; Baretta, E.; Moreno, J.A.; Junior, R. Autonomy Support, Motivation, Satisfaction and Physical Activity Level in Physical Education Class. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Mármol, A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F. School climate and responsibility as predictors of antisocial and prosocial behaviors and violence: A study towards self-determination theory. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Sánchez, D.; González-Villora, S.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Application of teaching personal and social responsibility model to the Secondary Education curriculum. Implications for students and teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, M.; Liang, G. Effects of teacher professional learning activities on student achievement growth. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeon, S.; Reeve, J.; Ntoumanis, N. An intervention to help teachers establish a prosocial peer climate in physical education. Learn. Instr. 2019, 64, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mármol, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; De La Cruz Sánchez, E. Perceived violence, sociomoral attitudes and behaviours in school contexts. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2018, 13, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rocha Alves, M.C.; Oliveira, K.C.; Moreira, M.V. School violence and the rise of urban criminality. Humanid. Inov. 2019, 6, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bejerot, S.; Plenty, A.; Humble, M.B. Humble. Poor Motor Skills: A Risk Marker for Bully Victimization. Aggress. Behav. 2013, 39, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, J.; Puhl, M.; Luedicke, J. An Experimental Investigation of Physical Education Teachers’ and Coaches’ Reactions to Weight-Based Victimization in Youth. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Villarino, M.; Gonzalez-Valeiro, M.; Toja-Reboredo, B.; Da Costa, F. Assesment About School and Physical Education and Its Relation with the Physical Activity of School. Retos 2017, 31, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Alekseev-Trifonov, S.; Merino-Barrero, J.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Moreno-Murcia, J. Teaching style for a lesser perception of violence of Physical Education. Rev. Int. De Cienc. Del Deporte 2021, 21, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasaescu, E.; Zych, I.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Farrington, D.P.; Llorent, V.J. Longitudinal Patterns of Antisocial Behaviors in Early Adolescence: A LatentClass and Latent Transition Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. 2020, 12, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B.J.; Thompson, K.; Sukhawathanakul, P. Enhancing social responsibility and prosocial leadership to prevent aggression, peer victimization, and emotional problems in elementary school children. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, C.; Escartí, A.; Llopis, G.; Gutiérrez, M. La percepción del profesorado de educación física sobre los efectos del program de responsabilidad personal y social en los estudiantes. Ágora 2011, 13, 341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M.; Pascual, C.; Llopis, R. Implementation of the Personal and Social responsibility Model to improve Self-efficacy during physical education classes for primary school children. Rev. Int. Psicol. Ter. Psicol. 2010, 10, 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Simonton, K.L.; Shiver, V.N. Examination of elementary students’ emotions and personal and social responsibility in physical education. Eur. Phy. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, D. Cómo Evaluar Bien en Educación Física: El Enfoque de la Evaluación Formativa; INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Sillero, D.; Corredor, F.; Córdoba, F.; Calmaestra, J. Intervention programme to prevent bullying in adolescents in physical education classes (PREBULLPE): A quasi-experimental study, Phys. Educ. Sport. Pedagog. 2021, 26, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range | M | SD | S | K | Ω | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Autonomy | 1–5 | 3.43 | 0.87 | −0.298 | −0.238 | 0.954 | - | 0.661 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.497 ** | 358 ** | 0.491 ** | 0.284 ** | 0.017 | 0.567 ** | 0.590 ** | −0.065 | 0.442 ** | 0.409 ** |

| 2 | Competence | 1–5 | 3.77 | 0.75 | −0.552 | 0.140 | 0.956 | - | 1 | 0.443 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.415 ** | 0.521 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.345 ** | −0.077 | 0.476 ** | 0.545 ** | −0.016 | 0.539 ** | 0.503 ** |

| 3 | Relatedness | 1–5 | 3.98 | 0.85 | −0.939 | 0.643 | 0.944 | - | - | 1 | 0.317 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.277 ** | −0.097 * | 0.541 ** | 0.487 ** | −0.117 * | 0.343 ** | 0.411 ** |

| 4 | IM_Knowledge | 1–7 | 4.90 | 1.31 | −0.494 | −0.112 | 0.961 | - | - | - | 1 | 0.680 ** | 0.707 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.655 ** | 0.397 ** | −0.057 | 0.420 ** | 0.471 ** | −0.061 | 0.476 ** | 0.410 ** |

| 5 | IM_Experience | 1–7 | 4.10 | 1.40 | −0.149 | −0.675 | 0.953 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.557 ** | 0.379 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.019 | 0.433 ** | 0.467 ** | −0.006 | 0.355 ** | 0.312 ** |

| 6 | IM_Achievement | 1–7 | 4.92 | 1.37 | −0.476 | −0.311 | 0.962 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.516 ** | 0.702 ** | 0.430 ** | −0.018 | 0.348 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.047 | 0.480 ** | 0.374 ** |

| 7 | Identified R. | 1–7 | 5.33 | 1.11 | −0.551 | −0.138 | 0.945 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.477 ** | 0.590 ** | −0.225 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.365 ** | −0.058 | 0.381 ** | 0.375 ** |

| 8 | Introjected R. | 1–7 | 5.10 | 1.31 | −0.557 | −0.253 | 0.954 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.449 ** | 0.057 | 0.382 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.051 | 0.445 ** | 0.367 ** |

| 9 | External R. | 1–7 | 5.78 | 1.06 | −0.819 | 0.233 | 0.949 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | −0.103 * | 0.170 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.043 | 0.324 ** | 0.313 ** |

| 10 | Amotivation | 1–7 | 2.23 | 1.45 | 1.184 | 0.648 | 0.960 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.001 | −0.076 | 0.199 ** | −0.142 ** | −0.142 ** |

| 11 | School climate | 1–5 | 3.41 | 0.77 | −0.165 | −0.255 | 0.900 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.716 ** | −0.202 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.439 ** |

| 12 | Teaching climate | 1–5 | 3.67 | 0.79 | −0.343 | −0.487 | 0.914 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | −0.136 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.443 ** |

| 13 | Violence | 1–5 | 2.34 | 0.89 | 0.484 | −0.308 | 0.885 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | −0.052 | −0.138 ** |

| 14 | Personal:_Responsibility | 1–6 | 4.92 | 0.85 | −0.836 | 0.086 | 0.902 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.650 ** |

| 15 | Social_Responsibility | 1–6 | 4.93 | 0.79 | −0.627 | −0.127 | 0.915 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Low Responsibility | Moderate Responsibility | High Responsibility | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | η | p | |

| Autonomy | 2.78 | 0.86 | 3.37 | 0.75 | 3.80 | 0.79 | 52.173 | 0.183 | ** |

| Competence | 3.03 | 0.80 | 3.75 | 0.58 | 4.14 | 0.61 | 91.172 | 0.281 | ** |

| Relatedness | 3.46 | 0.85 | 3.90 | 0.80 | 4.29 | 0.75 | 34.930 | 0.130 | ** |

| IM_Knowledge | 3.74 | 1.34 | 4.88 | 1.06 | 5.44 | 1.18 | 65.343 | 0.219 | ** |

| IM_Experience | 3.34 | 1.30 | 3.99 | 1.25 | 4.56 | 1.41 | 26.980 | 0.104 | ** |

| IM_Achievement | 3.72 | 1.34 | 4.98 | 1.14 | 5.43 | 1.25 | 59.587 | 0.203 | ** |

| Identified R. | 4.47 | 1.19 | 5.32 | 1.01 | 5.73 | 0.94 | 46.563 | 0.166 | ** |

| Introjected R. | 4.04 | 1.34 | 5.08 | 1.14 | 5.60 | 1.15 | 53.117 | 0.185 | ** |

| External R. | 5.09 | 1.18 | 5.81 | 1.00 | 6.08 | 0.91 | 29.957 | 0.114 | ** |

| Amotivation | 2.68 | 1.34 | 2.24 | 1.44 | 2.03 | 1.48 | 41.091 | 0.150 | ** |

| School climate | 2.99 | 0.70 | 3.26 | 0.73 | 3.75 | 0.70 | 57.182 | 0.197 | ** |

| Teaching climate | 3.09 | 0.75 | 3.57 | 0.69 | 4.04 | 0.72 | 52.173 | 0.183 | ** |

| Violence | 2.39 | 0.77 | 2.46 | 0.85 | 2.19 | 0.96 | 91.172 | 0.281 | * |

| Low Responsibility | Moderate Responsibility | High Responsibility | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | R | Total | % | R | Total | % | R | χ2 | gl | p | |

| Menu | 55 | 20.2% | 0.5 | 105 | 38.6% | −0.3 | 112 | 41.2% | 0 | 0.792 | 2 | 0.673 |

| Women | 34 | 17.2% | −0.6 | 82 | 41.4% | 0.4 | 82 | 41.4% | 0.1 | |||

| 11–13 | 24 | 16.9% | −0.6 | 62 | 43.7% | 0.7 | 56 | 39.4% | −0.3 | 3.394 | 4 | 0.494 |

| 14–15 | 29 | 17.2% | −0.5 | 64 | 37.9% | −0.4 | 76 | 45.0% | −0.7 | |||

| 16–20 | 36 | 22.6% | 1.1 | 61 | 38.4% | −0.3 | 62 | 39.0% | −0.4 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manzano-Sánchez, D. Physical Education Classes and Responsibility: The Importance of Being Responsible in Motivational and Psychosocial Variables. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610394

Manzano-Sánchez D. Physical Education Classes and Responsibility: The Importance of Being Responsible in Motivational and Psychosocial Variables. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610394

Chicago/Turabian StyleManzano-Sánchez, David. 2022. "Physical Education Classes and Responsibility: The Importance of Being Responsible in Motivational and Psychosocial Variables" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610394

APA StyleManzano-Sánchez, D. (2022). Physical Education Classes and Responsibility: The Importance of Being Responsible in Motivational and Psychosocial Variables. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610394