Going beyond “With a Partner” and “Intercourse”: Does Anything Else Influence Sexual Satisfaction among Women? The Sexual Satisfaction Comprehensive Index

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measure

2.3. Procedure

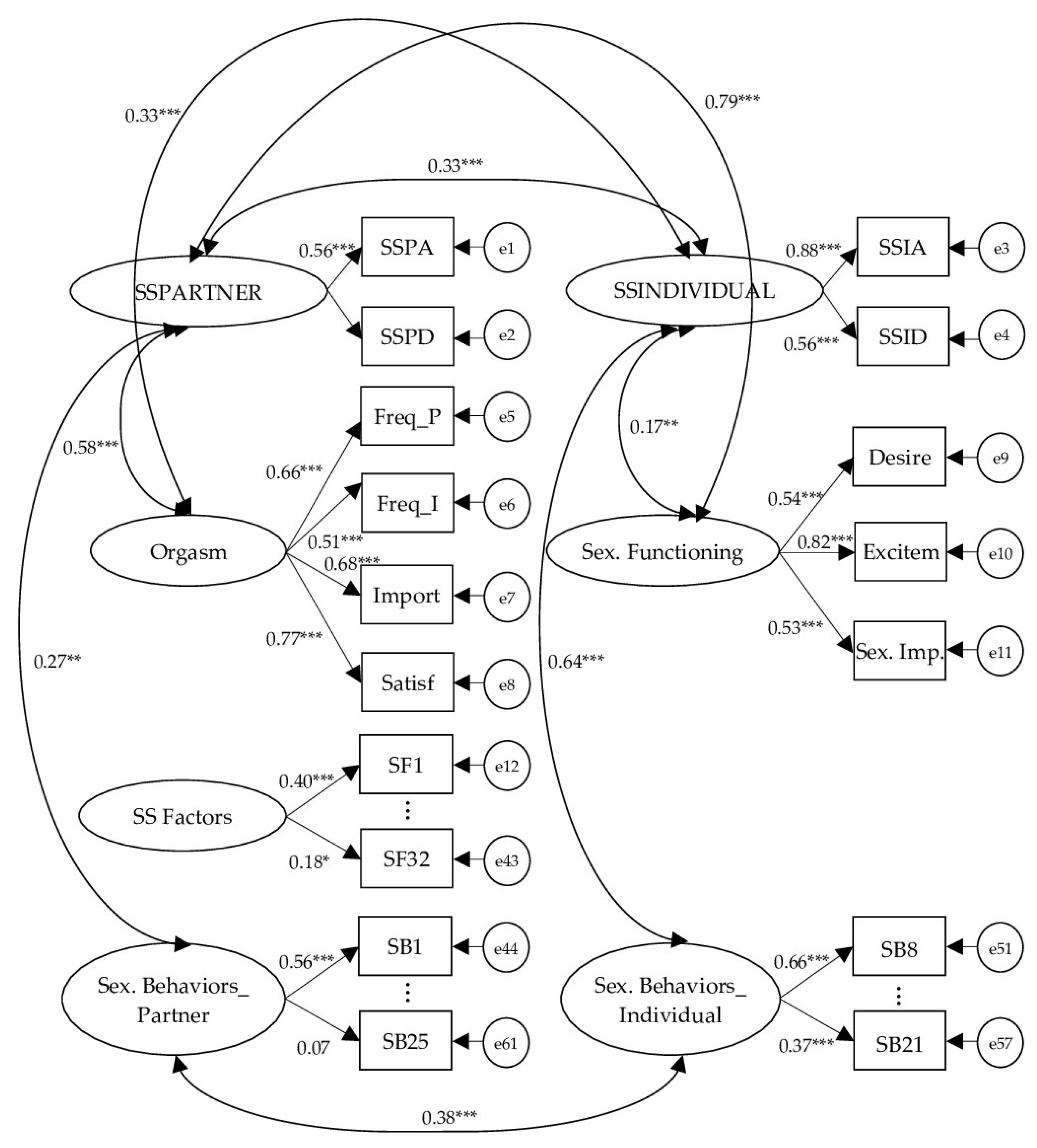

2.4. Study Design and Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| INDICADOR INTEGRAL DE SATISFACCIÓN SEXUAL (IISS) |

| [SEXUAL SATISFACTION COMPRENHENSIVE INDEX (SSCI)] |

- ☐

- Nada satisfactorias/No me interesa [Not satisfactory at all/Not interested in it]

- ☐

- Poco satisfactorias [Quite unsatisfactory]

- ☐

- Bastante satisfactorias [Quite satisfactory]

- ☐

- Muy satisfactorias [Very satisfactory]

- ☐

- Nada satisfactorias/No me interesa [Not satisfactory at all/Not interested in it]

- ☐

- Poco satisfactorias [Quite unsatisfactory]

- ☐

- Bastante satisfactorias [Quite satisfactory]

- ☐

- Muy satisfactorias [Very satisfactory]

- ☐

- Nada satisfactorias/No me interesa [Not satisfactory at all/Not interested in it]

- ☐

- Poco satisfactorias [Quite unsatisfactory]

- ☐

- Bastante satisfactorias [Quite satisfactory]

- ☐

- Muy satisfactorias [Very satisfactory]

- ☐

- Nada satisfactorias/No me interesa [Not satisfactory at all/Not interested in it]

- ☐

- Poco satisfactorias [Quite unsatisfactory]

- ☐

- Bastante satisfactorias [Quite satisfactory]

- ☐

- Muy satisfactorias [Very satisfactory]

- ☐

- Nunca he tenido un orgasmo [I have never reached an orgasm]

- ☐

- A veces [Sometimes]

- ☐

- Bastantes veces [Quite a few times]

- ☐

- Casi siempre o siempre [Almost always or always]

- ☐

- Nunca he tenido un orgasmo [I have never reached an orgasm]

- ☐

- A veces [Sometimes]

- ☐

- Bastantes veces [Quite a few times]

- ☐

- Casi siempre o siempre [Almost always or always]

- ☐

- No. Disfruto plenamente con mis prácticas sexuales sin orgasmos [No. I fully enjoy my practices without having an orgasm]

- ☐

- No. Realmente me da igual si tengo orgasmos o no, lo que me hace quedar satisfecha son otros factores [No. I really don’t care if I have orgasms or not, what makes me satisfied are other factors]

- ☐

- No necesariamente. Me gusta más cuando tengo orgasmos, pero puedo disfrutar una práctica que no termina en orgasmo y sentirme satisfecha al terminar [Not necessarily. I like it better when I have orgasms, but I can enjoy a practice that does not end in orgasm and feel satisfied with it]

- ☐

- Sí, generalmente sólo me siento completamente satisfecha si logro tener al menos un orgasmo [Yes, I usually only feel fully satisfied if I manage to have at least one orgasm]

- ☐

- Sí, generalmente sólo me siento completamente satisfecha si logro tener más de un orgasmo [Yes, I usually only feel fully satisfied if I manage to have more than one orgasm]

- ☐

- Generalmente no tengo orgasmos, así que disfruto con mis prácticas sin orgasmos [I usually don’t have orgasms, so I enjoy my practices without orgasms]

- ☐

- Igual que cuando no lo alcanzo, mi satisfacción no depende en absoluto de tener orgasmos [Just like when I don’t reach it, my satisfaction doesn’t depend on having orgasms at all]

- ☐

- Algo más satisfactorias [Somewhat more satisfactory]

- ☐

- Bastante más satisfactorias [Quite more satisfactory]

- ☐

- Mucho más satisfactorias [Much more satisfactory]

- ☐

- Yo sólo me siento completamente satisfecha si logro tener al menos un orgasmo [I only feel completely satisfied if I manage to have at least one orgasm]

- ☐

- Nada de deseo [Null]

- ☐

- Muy bajo [Very low]

- ☐

- Moderado [Moderate]

- ☐

- Alto [High]

- ☐

- Muy alto [Very high]

- ☐

- Nada de excitación [Null]

- ☐

- Muy bajo [Very low]

- ☐

- Moderado [Moderate]

- ☐

- Alto [High]

- ☐

- Muy alto [Very high]

| ¿En qué medida lo siguiente influye en tu satisfacción sexual...? [How much do the following aspects influence your sexual satisfaction…?] | No me afecta en nada [It does not affect me at all] | Me afecta algo [It only affects me a little] | Me afecta bastante [It affects me somewhat] | Me afecta mucho [It affects me a lot] |

| …lo que hagas tú (p.e., las técnicas que uses) [...whatever I do (e.g., the techniques I use)] | ||||

| …lo que hagan otras personas cuando están conmigo (p.e., las técnicas que usan) [...whatever others do when they are with me (e.g., the techniques my sexual partner(s) use)] | ||||

| …la comunicación (esto es, decir/transmitir lo que te gusta/no te gusta o lo que te apetece/no te apetece hacer) […communication (i.e., stating what I like/dislike or I want/don’t want to do)] | ||||

| …sentir atracción por tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) [...feeling attracted to my sexual partner(s)] | ||||

| …el deseo/las ganas que tengas de tener una relación sexual, de hacer algo sexual [...desiring to have a sexual relationship, sexual activity] | ||||

| …la concentración, que no estés pensando en otras cosas […my concentration levels, not dwelling on something else] | ||||

| …la experiencia/conocimiento que tengas/tengáis […the experience/knowledge I/we have] | ||||

| …tu habilidad [...my own ability] | ||||

| …la habilidad de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) […my sexual partner’s(partners’) ability] | ||||

| …la disposición que tengas a probar cosas nuevas (p.e., innovación, creatividad...) […my disposition to try new things (e.g., innovation, creativity)] | ||||

| …que estés tranquila/relajada/a gusto, que nada/nadie te moleste […feeling relaxed/comfortable, unbothered by anything/anyone] | ||||

| …tu habilidad para decir a tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) cosas bonitas/agradables, o de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) para decirte cosas bonitas/agradables a ti […the ability to express/say pretty/pleasant things to my sexual partner(s) or my sexual partner’s (partners’) ability to do that to me] | ||||

| …tu habilidad para decir a tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) cosas eróticas, o de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) para decirte cosas eróticas a ti […the ability to express/say erotic things to my sexual partner(s) or my sexual partner’s (partners’) ability to do that to me] | ||||

| …que vivas la sexualidad como algo normal/sano/deseable […experiencing sexuality as something normal/healthy/desirable] | ||||

| …que no te sientas obligada a hacer algo que no quieres/que no te apetece hacer […not feeling obligated to do something I don’t want/desire to do] | ||||

| …“Echarle picante al guiso”, “darle morbo” […making something/someone horny] | ||||

| …la compenetración que tengas con tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) […having confidence with my sexual partner(s)] | ||||

| …el método anticonceptivo que uséis […the contraceptive method used] | ||||

| …que ames a tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es)/que ésta/e(s) te ame(n) […loving my sexual partner(s) or being loved by her/him/them] | ||||

| …la confianza/seguridad que tengas en tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) […the faith/truth/security with my sexual partner(s)] | ||||

| …tu nivel de autoestima […my self-esteem levels] | ||||

| …que te sientas cómoda con tu cuerpo/que no sientas vergüenza de tu cuerpo […feeling comfortable with my body/not feeling ashamed] | ||||

| …que tú llegues al orgasmo […me reaching climax] | ||||

| …que tú y tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) lleguéis al orgasmo […me and my partner(s) reaching climax] | ||||

| …el sitio donde practicas actividades sexuales (p.e., ruido, tranquilidad, la posibilidad de que te pillen sin querer o queriendo, interrupciones) […the place where the encounter takes place (e.g., noise, peace, the chance of getting caught deliberately or not, interruptions)] | ||||

| …que estés muy excitada […being very sexually excited] | ||||

| …que sientas que tienes futuro con tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es), que tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) está(n) comprometido/a/s con la relación […feeling that my sexual partner(s) is committed to the relationship] | ||||

| …que estés feliz, contenta […feeling contented or happy] | ||||

| …tener el mismo nivel de deseo sexual que tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) […me and my partner(s) having the same level of desire] | ||||

| …que haya respeto, que haya fidelidad […having respect for, faithfulness to each other] | ||||

| …que no estés cansada […not being tired] | ||||

| …que utilicéis fantasías, juegos, juguetes, etc. […using sexual fantasies, role-playing, erotic toys...] |

| ¿En qué medida influyen los siguientes comportamientos en tu satisfacción sexual? [How much do the following behaviors influence your sexual satisfaction…?] | No lo practico [I do not practice it] | Nada satisfactorio [Not satisfactory at all] | Algo satisfactorio [Somewhat satisfactory] | Bastante satisfatorio [Quite satisfactory] | Muy satisfactorio [Very satisfactory] |

| Besarse [Kissing] | |||||

| Acariciarse [Cuddling] | |||||

| Abrazarse [Hugging] | |||||

| Lamer o morder suavemente a tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es), ser lamida o mordida suavemente [Licking or biting my sexual partner(s), being licked/bitten by her/him/them] | |||||

| Dar sexo oral (es decir, felación, cunnilingus) [Giving oral sex (i.e., fellatio/cunnilingus)] | |||||

| Recibir sexo oral (es decir, cunnilingus) [Receiving oral sex (i.e., cunnilingus)] | |||||

| Dar o recibir sexo oral anal (es decir, anilingus) [Giving or receiving anal oral sex (i.e., anilingus)] | |||||

| Automasturbación (es decir, autoestimulación manual de los órganos sexuales propios) [Masturbation (i.e., manual self-stimulation of the own genitalia)] | |||||

| Heteromasturbación (es decir, estimulación manual de los órganos sexuales de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es), o ser estimulada manualmente en los órganos sexuales por esta(s) persona(s), simultáneamente o no) [Hetero-masturbation (i.e., manual stimulation of sexual partner’s(partners’) genitalia, or being manually stimulated on the genitalia by the partner(s), simultaneously or not)] | |||||

| Coito vaginal (es decir, introducción pene-vagina) [Vaginal intercourse (i.e., penis-vagina introduction)] | |||||

| Coito anal (es decir, introducción pene-ano) [Anal intercourse (i.e., penis-anus introduction)] | |||||

| Imaginar/fantasear con otros contextos, situaciones, personas [Using my imagination/fantasies regarding other contexts, situations, people…] | |||||

| Poner en práctica alguna fantasía sexual, probarla [Putting into practice any sexual fantasy, practicing it] | |||||

| Jugar a la seducción con tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) (p.e., ligar, hacer striptease, etc.) [Erotic play, seducing my partner(s) (e.g., flirting, performing a striptease)] | |||||

| Acariciar sexualmente el cuerpo de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) sin ropa y sin incluir los órganos sexuales (petting) [Petting] | |||||

| Acariciar sexualmente el cuerpo de tu(s) pareja(s) sexual(es) sin ropa, incluyendo los órganos sexuales (heavy petting) [Heavy petting] | |||||

| Imitar los movimientos del coito (pseudo-coito) [Pseudo-coitus (i.e., imitate intercourse movements)] | |||||

| Usar juguetes sexuales (p.e., balas vibradoras, “satisfier”, anillos vibradores para el pene, estimuladores del clítoris) [Using sex toys (e.g., bullet vibrator, “satisfier”, penis rings, clitoral stimulators)] | |||||

| Usar literatura erótica/pornográfica (p.e., novelas, cómics) [Using erotic/pornographic literature (e.g., novels, comics)] | |||||

| Usar material visual erótico/pornográfico (p.e., películas, fotografías, vídeos) [Using erotic/pornographic visual media (e.g., movies, photos, videos)] | |||||

| Realizar prácticas en las que se retrasa o impide el orgasmo (p.e., sexo tántrico) [Engaging in sexual practices aimed to delay or impede climax (e.g., tantric sex)] | |||||

| Realizar prácticas más provocadoras, pero con poco o ningún riesgo (p.e., pellizcos, usar ataduras, pegar cachetes, tapar los ojos) [Engaging in more provocative but non-risky sexual practices (e.g., pinching, using ties, slapping, covering the eyes)] | |||||

| Realizar prácticas un poco más agresivas, que requieren de palabras de seguridad (p.e., BDSM) [Engaging in more aggressive sexual practices, ones that require safe-words (e.g., BDSM)] | |||||

| Practicar sexo con más de una pareja sexual (p.e., tríos, intercambio de parejas (swinging), orgías, dogging) [Engaging in sex with more than one sexual partner (e.g., threesomes, swinging, orgies, dogging)] | |||||

| Realizar prácticas que pueden ser potencialmente arriesgadas (p.e., con desconocidas/os, salas oscuras, ruletas) [Engaging in potentially risky sexual practices (e.g., with unknown people, in dark rooms, sex roulettes)] |

- ☐

- Nada importante [Not important at all]

- ☐

- Poco importante, hay otras cosas más importantes para mí [Not very important, there are other things more important to me]

- ☐

- Bastante importante [Quite important]

- ☐

- Muy importante [Very important]

References

- Carrobles, J.A.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Almendros, C. Funcionamiento sexual, satisfacción sexual y bienestar psicológico y subjetivo en una muestra de mujeres españolas. An. Psicol. 2011, 27, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- McCool, M.E.; Apfelbacher, C.; Brandstetter, S.; Mottl, M.; Loss, J. Diagnosing and treating female sexual dysfunction: A survey of the perspectives of obstetricians and gynaecologists. Sex. Health 2016, 13, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenor, S. Sexual counter-revolution. First Things 2021, 317, 27–34. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2595667959?accountid%20=%2014542 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Rosen, R.C.; Bachmann, G.A. Sexual well-being, happiness and satisfaction in women: The case for a new conceptual paradigm. J. Sex Mar. Ther. 2008, 34, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.V.; Corona-Vargas, E.; Cruz, M.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Kismodi, E.; Philpott, A.; Rubio-Aurioles, E.; Coleman, E. The World Association for Sexual Health’s Declaration on sexual pleasure: A technical guide. Int. J. Sex. Health 2021, 33, 612–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Melisaratos, N. The DSFI: A multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1979, 5, 244–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, J.; Golombok, S. The Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS). Clin. Psychol. 1985, 24, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.F.; Rosen, R.C.; Leiblum, S.R. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1994, 23, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Mar. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, W.W.; Harrison, D.F.; Crosscup, P.C. Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS). A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J. Sex Res. 1981, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, K.A.; Byers, S.E. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal relation model of sexual satisfaction. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 2, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meston, C.; Trapnell, P. Outcomes assessment: Development and validation of a five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale for women: The sexual satisfaction scale for women (SSS-W). J. Sex. Med. 2005, 2, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štulhofer, A.; Buško, V.; Brouillard, P. Development and bicultural validation of the New Sexual Satisfaction Scale. J. Sex Res. 2010, 47, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fuentes, M.; del Mar Santos-Iglesias, P.; Sierra, J.C. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, L. Female Sexual Satisfaction and Sexual Identity. Doctoral Dissertation, Proquest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, A.B. Dimensions of couples’ sexual communication, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.M. Sexual satisfaction in Portuguese women: Differences between women with clinical, self-perceived and absence of sexual difficulties. Int. J. Sex. Health 2022, 34, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.M.; Lopes, J. Solitary and dyadic sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in women with and without sexual concerns. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlich, M.; Nouri, N.; Jensen, R.; Meuwly, N.; Schoebi, D. Associations of conflict frequency and sexual satisfaction with weekly relationship satisfaction in Iranian couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, E.E.; Rehman, U.S.; Woody, E.Z.; Purdon, C. The longitudinal association of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, J.K.; Wenner, C.A.; Fisher, T.D. Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and frequency of sex in early marriage. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Robinson, W.D.; Seedall, R.B. The role of sexual communication in couples’ sexual outcomes: A dyadic path analysis. J. Mar. Fam. Ther. 2018, 44, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnie-Porter, C.; Hunt, M. Does relationship status matter for sexual satisfaction? The roles of intimacy and attachment avoidance in sexual satisfaction across five types of ongoing sexual relationships. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2015, 24, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H.; Campbell, L. Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2012, 3, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, E.A.; Loving, T.J.; Pope, M.T.; Huston, T.L.; Štulhofer, A. Does sex really matter? Examining the connections between spouses’ nonsexual behaviors, sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 46, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; de Oliveira, L.; Oliveira, C.; Nobre, P. Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of women’s sexual pleasure: A scoping review. Int. J. Sex. Health 2021, 33, 494–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levay, S.; Valente, S.M. Human Sexuality, 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T.D.; Davis, C.M.; Yarber, W.L.; Davis, S.L. Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Milhausen, R.R.; Sakaluk, J.K.; Fisher, T.D.; Davis, C.M.; Yarber, W.L. Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ogallar-Blanco, A.I.; Godoy-Izquierdo, D.; Vázquez, M.L.; Godoy, J.F. Sexual satisfaction among young women: The frequency of sexual activities as a mediator. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, V.; Van der Schouw, Y.T.; Onland-Moret, N.C.; Groenwold, R.H.; Peters, S.A.; Burgess, S.; Butterworth, A. Association of menopausal characteristics and risk of coronary heart disease: A pan-European case-cohort analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroy, C.; Marin Martin, C.; López-Picado, A. The impact of perimenopausal symptomatology, sociodemographic status and knowledge of menopause on women´s quality of life. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.C.; Santos, P.; García, M.; Sánchez, A.; Martínez, A.; Tapia, M.I. Índice de Satisfacción Sexual (ISS): Un estudio sobre su fiabilidad y validez. Rev. Int. Psicol. Ter. Psicol. 2009, 9, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizzi, J.; Fernández-Agis, I.; Alarcón-Rodríguez, R.; Parrón-Carreño, T. New sexual satisfaction scale-short form—Spanish version. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2016, 42, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Hernández, A.I.; Parra-Carrillo, W.C.; Álvarez-Muelas, A.; Peñuela-Trujillo, C.; Rosero, F.; de la Hoz, F.E.; González, J.M.; Saffon, P.; Vélez, D.; Franco, E.; et al. Temporal stability and clinical validation of the Spanish version of the female sexual function inventory (FSFI). Women Health 2020, 61, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassim, S.; Hasan, H.; Ismon, A.M.; Asri, F.M. Parameter estimation in factor analysis: Maximum likelihood versus principal component. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013, 1522, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M. A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Decisions and overview of current practices: What we are doing and how can we improve? Int. J. Hum.-Comp. Interact. 2015, 32, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, D. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Meth. 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, R.K.; Roberts, J.K. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Reguant-Álvarez, M. Calcular la fiabilidad de un cuestionario o escala mediante el SPSS: El coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. REIRE Rev. D’innovació Recerca Educ. 2020, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbenick, D.; Eastman-Mueller, H.; Fu, T.-C.; Dodge, B.; Ponander, K.; Sanders, S.A. Women’s sexual satisfaction, communication, and reasons for (no longer) faking orgasm: Findings from a U.S. probability sample. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2461–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, A.M.; Zaikman, Y. The big “O”: Sociocultural influences on orgasm frequency and sexual satisfaction in women. Sex. Cult. 2021, 25, 1096–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, O.; Sierra, J.C. Masturbation parameters related to orgasm satisfaction in sexual relationships: Differences between men and women. Front. Psych. 2022, 13, 903361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, M. Anorgasmia in women. J. Fam. Psychother. 2009, 20, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, D.; Rettenberger, M. Predictors of sexual satisfaction in women: A systematic review. Sex. Med. Rev. 2021, 9, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, W.A.; Donahue, K.L.; Long, J.S.; Heiman, J.R.; Rosen, R.C.; Sand, M.S. Individual and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife couples: Dyadic analysis of the International Survey of Relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 1609–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Macdonald, G. Single and partnered individuals’ sexual satisfaction as a function of sexual desire and activities: Results using a sexual satisfaction scale demonstrating measurement invariance across partnership status. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, M.; Milhausen, R.R.; Quinn-Nilas, C. Motives between the sheets: Understanding obligation for sex at midlife and associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction. J. Sex Res. 2022, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, D.L.; Kolba, T.N.; McNabney, S.M.; Uribe, D.; Hevesi, K. Why and how women masturbate, and the relationship to orgasmic response. J. Sex Mar. Ther. 2020, 46, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onar, D.K.; Armstrong, H.; Graham, C.A. What does research tell us about women’s experiences, motives and perceptions of masturbation within a relationship context?: A systematic review of qualitative studies. J. Sex Mar. Ther. 2020, 46, 683–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerwenka, S.; Dekker, A.; Pietras, L. Single and multiple orgasm experience among women in heterosexual partnerships. results of the German health and sexuality survey (GeSiD). J. Sex Med. 2021, 18, 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, N.D.; Willoughby, B.J.; Busby, D.M.; Yorgason, J.B.; Holmes, E.K. The significance of the female orgasm: A nationally representative, dyadic study of newlyweds’ orgasm experience. J. Sex Med. 2018, 15, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, S.I. “What do you mean when you say that you are sexually satisfied?” A mixed methods study. Fem. Psychol. 2014, 24, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontula, O.; Miettinen, A. Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffect. Neurosci. Psychol. 2016, 6, 31624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döring, N.; Poeschl, S. Experiences with diverse sex toys among German heterosexual adults: Findings from a national online survey. J. Sex Res. 2019, 57, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Vallejo, P. El Análisis Factorial en la Construcción e Interpretación de Test, Escalas y Cuestionarios; Universidad Pontificia de Comillas: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Delamater, J.; Karraker, A. Sexual functioning in older adults. Cur. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Educational Level | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Uneducated | 2 | 0.2 |

| Primary School | 12 | 1.1 |

| Secondary School | 23 | 2.1 |

| Professional Training | 53 | 4.9 |

| University | 862 | 79.8 |

| University Postgraduate (Master/PhD) | 128 | 11.9 |

| Religion/Spiritual Factors | N | % |

| Catholic | 477 | 44.1 |

| Buddhist | 7 | 0.6 |

| Muslim | 6 | 0.6 |

| Protestant | 5 | 0.5 |

| Agnostic | 149 | 13.8 |

| Atheist | 433 | 40.1 |

| Other | 3 | 0.3 |

| Level of Religiosity | N | % |

| Not religious at all | 532 | 49.3 |

| Not very/A little religious | 381 | 35.3 |

| Quite religious | 121 | 11.2 |

| Very religious | 46 | 4.2 |

| Political Ideology | N | % |

| None | 128 | 11.9 |

| Conservative | 33 | 3.1 |

| Centre | 198 | 18.3 |

| Progressive | 533 | 49.4 |

| Not identified by the participant | 188 | 17.3 |

| Cohabitation | N | % |

| Alone | 56 | 5.2 |

| With friends | 375 | 34.7 |

| With partner | 143 | 14.8 |

| With family of origin (parents, siblings…) | 444 | 39.6 |

| With family of procreation (offspring) | 57 | 5.2 |

| Student residence | 5 | 0.5 |

| Number of Sporadic Sexual Partners | N | % |

| None | 487 | 45.1 |

| 1 to 5 | 315 | 29.2 |

| 5 to 10 | 144 | 13.3 |

| 10 to 20 | 104 | 9.6 |

| More than 20 | 30 | 2.8 |

| Number of Committed Sexual Partners | N | % |

| None | 368 | 34.1 |

| 1 to 5 | 621 | 57.5 |

| 5 to 10 | 73 | 6.7 |

| 10 to 20 | 16 | 1.5 |

| More than 20 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Variable (Possible Scores Range) | M ± SD [Min–Max in the Sample] |

|---|---|

| Actual Individual Sexual Satisfaction (0–3) | 2.09 ± 0.83 [0–3] |

| Actual With the Partner(s) Sexual Satisfaction (0–3) | 2.23 ± 0.70 [0–3] |

| Desired Individual Sexual Satisfaction (0–3) | 2.6 ± 0.83 [0–3] |

| Desired With the Partner(s) Sexual Satisfaction (0–3) | 2.9 ± 0.33 [0–3] |

| Orgasm Frequency With a Partner(s) (0–3) | 2.05 ± 0.97 [0–3] |

| Orgasm Frequency in Individual Practices (0–3) | 2.17 ± 1.11 [0–3] |

| Orgasm Importance (0–4) | 2.31 ± 0.77 [0–4] |

| Overall Satisfaction When Orgasm (0–5) | 3.14 ± 1.25 [0–5] |

| Desire Level (0–4) | 2.95 ± 0.77 [0–4] |

| Excitement Level (0–4) | 3.01 ± 0.74 [0–4] |

| Sexuality Importance (0–3) | 2.18 ± 0.71 [0–3] |

| Factors that affect Sexual Satisfaction a (0–3) | 2.12 ± 0.36 [1–3] |

| Sexual Behaviors that affect Sexual Satisfaction a (0–4) | 1.34 ± 1.2 [0–4] |

| ISS a (1–7) | 5.68 ± 0.93 [1–7] |

| NSSS-S a (1–5) | 3.81 ± 0.70 [1–5] |

| FSFI a (0–5) | 3.95 ± 1.18 [1–5] |

| How Much Do the Following Aspects Influence Your Sexual Satisfaction…?] | It Does Not Affect Me at All (%) | It Only Affects Me a Little (%) | It Affects Me Somewhat (%) | It Affects Me a Lot (%) | M ± SD [Min–Max in the Sample] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ...whatever I do (e.g., the techniques I use) | 3.5 | 18.3 | 50.7 | 27.5 | 2.02 ± 0.77 [0–3] |

| ...whatever others do when they are with me (e.g., the techniques my sexual partner(s) use) | 0.4 | 5.2 | 40.6 | 53.7 | 2.48 ± 0.62 [0–3] |

| …communication (i.e., stating what I like/dislike or I want/don’t want to do) | 0.9 | 14.4 | 45.4 | 39.3 | 2.23 ± 0.72 [0–3] |

| ...feeling attracted to my sexual partner(s) | 0 | 2.6 | 24.9 | 72.5 | 2.70 ± 0.51 [1–3] |

| ...desiring to have a sexual relationship, sexual activity | 0.4 | 5.2 | 30.6 | 63.8 | 2.58 ± 0.61 [0–3] |

| …my concentration levels, not dwelling on something else | 2.6 | 20.1 | 31 | 46.3 | 2.21 ± 0.85 [0–3] |

| …the experience/knowledge I/we have | 5.2 | 26.2 | 45.4 | 23.1 | 1.86 ± 0.83 [0–3] |

| ...my own ability | 4.4 | 27.9 | 47.2 | 20.5 | 1.84 ± 0.80 [0–3] |

| …my sexual partner’s (partners’) ability | 2.2 | 15.3 | 48.5 | 34.1 | 2.14 ± 0.75 [0–3] |

| …my disposition to try new things (e.g., innovation, creativity) | 2.2 | 21.8 | 46.7 | 29.3 | 2.03 ± 0.77 [0–3] |

| …feeling relaxed/comfortable, unbothered by anything/anyone | 1.3 | 9.2 | 38 | 51.5 | 2.40 ± 0.71 [0–3] |

| …the ability to express/say pretty/pleasant things to my sexual partner(s) or my sexual partner’s (partners’) ability to do that to me | 6.1 | 27.5 | 34.1 | 32.3 | 1.93 ± 0.92 [0–3] |

| …the ability to express/say erotic things to my sexual partner(s) or my sexual partner’s (partners’) ability to do that to me | 5.7 | 17.5 | 36.7 | 40.2 | 2.11 ± 0.89 [0–3] |

| …experiencing sexuality as something normal/healthy/desirable | 1.7 | 5.2 | 27.5 | 65.5 | 2.57 ± 0.58 [0–3] |

| …not feeling obligated to do something I don’t want/desire to do | 2.6 | 4.4 | 21 | 72.1 | 2.62 ± 0.69 [0–3] |

| …making something/someone horny | 3.5 | 16.6 | 41.9 | 38 | 2.14 ± 0.82 [0–3] |

| …having confidence with my sexual partner(s) | 1.3 | 5.2 | 26.6 | 66.8 | 2.6 ± 0.65 [0–3] |

| …the contraceptive method used | 21.4 | 38.4 | 26.2 | 14 | 1.33 ± 0.96 [0–3] |

| …loving my sexual partner(s) or being loved by her/him/them | 9.2 | 26.2 | 25.8 | 38.9 | 1.94 ± 1 [0–3] |

| …the faith/truth/security with my sexual partner(s) | 0 | 7.4 | 32.8 | 59.8 | 2.52 ± 0.63 [1–3] |

| …my self-esteem levels | 1.7 | 7.9 | 36.2 | 54.1 | 2.43 ± 0.71 [0–3] |

| …feeling comfortable with my body/not feeling ashamed | 0.9 | 7.9 | 27.9 | 63.3 | 2.54 ± 0.58 [0–3] |

| …me reaching climax | 6.6 | 29.7 | 44.1 | 19.7 | 1.77 ± 0.84 [0–3] |

| …me and my partner(s) reaching climax | 4.4 | 20.5 | 45 | 30.1 | 2.01 ± 0.83 [0–3] |

| …the place where the encounter takes place (e.g., noise, peace, the chance of getting caught deliberately or not, interruptions) | 4.4 | 23.1 | 36.7 | 35.8 | 2.04 ± 0.87 [0–3] |

| …being very sexually excited | 0.9 | 7 | 36.2 | 55.9 | 2.74 ± 0.67 [0–3] |

| …feeling that my sexual partner(s) is committed to the relationship | 26.6 | 38.9 | 20.5 | 14 | 1.22 ± 0.99 [0–3] |

| …feeling contented or happy | 1.3 | 12.7 | 40.2 | 45.9 | 2.31 ± 0.74 [0–3] |

| …me and my partner(s) having the same level of desire | 11.8 | 36.7 | 35.4 | 16.2 | 1.56 ± 0.90 [0–3] |

| …having respect for, faithfulness to each other | 3.1 | 12.2 | 35.4 | 49.3 | 2.31 ± 0.80 [0–3] |

| …not being tired | 3.9 | 25.8 | 38.4 | 31.9 | 1.98 ± 0.86 [0–3] |

| …using sexual fantasies, role-playing, erotic toys... | 22.7 | 49.3 | 19.7 | 8.3 | 1.14 ± 0.86 [0–3] |

| How Much Do the Following Behaviors Influence Your Sexual Satisfaction…? | I Do Not Practice It (%) | Not Satisfactory at All (%) | Somewhat Satisfactory (%) | Quite Satisfactory (%) | Very Satisfactory (%) | M ± SD [Min–Max in the Sample] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kissing | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 20.2 | 77.6 | 3.74 ± 0.55 [0–4] |

| Cuddling | 0 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 19.7 | 78.5 | 3.76 ± 0.48 [1–4] |

| Hugging | 0 | 0.9 | 6.6 | 20.6 | 71.9 | 3.64 ± 0.65 [1–4] |

| Licking or biting my sexual partner(s), being licked/bitten by her/him/them | 0.4 | 0 | 8.3 | 28.5 | 62.7 | 3.53 ± 0.58 [0–4] |

| Giving oral sex (i.e., fellatio/cunnilingus) | 3.5 | 6.1 | 14 | 36.8 | 39.5 | 3.03 ± 1.05 [0–4] |

| Receiving oral sex (i.e., cunnilingus) | 5.3 | 3.1 | 10.5 | 21.9 | 59.2 | 3.27 ± 1.11 [0–4] |

| Giving or receiving anal oral sex (i.e., anilingus) | 63.6 | 6.1 | 13.6 | 7 | 9.6 | .93 ± 1.39 [0–4] |

| Masturbation (i.e., manual self-stimulation of the own genitalia) | 7.9 | 3.9 | 14.9 | 34.2 | 39 | 2.93 ± 1.19 [0–4] |

| Hetero-masturbation (i.e., manual stimulation of sexual partner’s(partners’) genitalia, or being manually stimulated on the genitalia by the partner(s), simultaneously or not) | 1.8 | 13 | 12.7 | 39 | 45.2 | 3.25 ± 0.86 [0–4] |

| Vaginal intercourse (i.e., penis-vagina introduction) | 3.9 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 18.9 | 70.6 | 3.51 ± 0.95 [0–4] |

| Anal intercourse (i.e., penis-anus introduction) | 62.3 | 10.5 | 14.5 | 9.2 | 3.5 | 0.81 ± 1.2 [0–4] |

| Using my imagination/fantasies regarding other contexts, situations, people… | 10.5 | 14.5 | 35.1 | 25 | 14.9 | 2.19 ± 1.17 [0–4] |

| Putting into practice any sexual fantasy, practicing it | 13.2 | 7.9 | 18.4 | 36.8 | 23.7 | 2.5 ± 1.3 [0–4] |

| Erotic play, seducing my partner(s) (e.g., flirting, performing a striptease) | 9.2 | 5.3 | 24.6 | 35.5 | 25.4 | 2.63 ± 1.19 [0–4] |

| Petting | 1.8 | 1.8 | 19.3 | 40.4 | 36.8 | 3.09 ± 0.87 [0–4 |

| Heavy petting | 1.8 | .9 | 8.3 | 42.1 | 46.9 | 3.32 ± 0.8 [0–4] |

| Pseudo-coitus (i.e., imitate intercourse movements) | 6.6 | 8.8 | 27.2 | 32.9 | 24.6 | 2.60 ± 1.14 [0–4] |

| Using sex toys (e.g., bullet vibrator, “satisfier”, penis rings, clitoral stimulators) | 36.8 | 7.5 | 21.5 | 18.9 | 15.4 | 1.68 ± 1.05 [0–4] |

| Using erotic/pornographic literature (e.g., novels, comics) | 42.5 | 11.4 | 26.8 | 12.3 | 7 | 1.30 ± 1.32 [0–4] |

| Using erotic/pornographic visual media (e.g., movies, photos, videos) | 31.6 | 12.3 | 26.8 | 17.5 | 11.8 | 1.66 ± 1.39 [0–4] |

| Engaging in sexual practices aimed to delay or impede climax (e.g., tantric sex) | 66.2 | 6.6 | 11 | 9.2 | 7 | 0.84 ± 1.32 [0–4] |

| Engaging in more provocative but non-risky sexual practices (e.g., pinching, using ties, slapping, covering the eyes) | 26.8 | 6.1 | 18 | 27.2 | 21.9 | 2.11 ± 1.5 [0–4] |

| Engaging in more aggressive sexual practices, ones that require safe-words (e.g., BDSM) | 82.9 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 0.41 ± 1 [0–4] |

| Engaging in sex with more than one sexual partner (e.g., threesomes, swinging, orgies, dogging) | 82 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 0.46 ± 1.09 [0–4] |

| Engaging in potentially risky sexual practices (e.g., with unknown people, in dark rooms, sex roulettes) | 90.8 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.19 ± 0.67 [0–4] |

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Actual Individual SS | 0.186 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.162 ** | 0.638 ** | 0.146 ** | 0.231 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.131 ** | 0.134 ** | 0.228 ** | |||||

| 2. Actual With the Partner(s) SS | - | 0.074 * | 0.185 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.146 ** | 0.238 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.468 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.644 ** | 0.529 ** | ||

| 3. Desired Individual SS | - | 0.231 ** | 0.399 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.102 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.072 * | 0.092 * | |||||||

| 4. Desired With the Partner(s) SS | - | 0.119 ** | 0.092 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.113 ** | 0.169 * | 0.171 ** | 0.241 ** | 0.121 ** | 0.120 ** | 0.151 ** | ||||

| 5. Orgasm Freq. With a Partner(s) | - | 0.366 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.210 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.533 ** | 0.326 ** | ||||||

| 6. Orgasm Freq. in Individual Practices | - | 0.275 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.135 * | 0.136 * | 0.142 ** | 0.130 ** | 0.235 ** | |||||||

| 7. Orgasm Importance | - | 0.606 ** | 0.098 ** | 0.174 ** | |||||||||||

| 8. Overall Satisfaction When Orgasm | - | 0.136 * | 0.185 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.127 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.091 * | |||||||

| 9. Desire Level | - | 0.420 ** | 0.309 ** | ||||||||||||

| 10. Excitement Level | - | 0.380 ** | 0.142 * | ||||||||||||

| 11. Sexuality Importance | - | 0.254 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.197 ** | ||||||||||

| 12. Factors that affect SS a | - | ||||||||||||||

| 13. Sexual Behaviors that affect SS a | - | ||||||||||||||

| 14. ISS a | - | 0.777 ** | 0.607 ** | ||||||||||||

| 15. NSSS-S a | - | 0.564 ** | |||||||||||||

| 16. FSFI a | - |

| Factor 1 SS Factors | Factor 2 Individual SS | Factor 3 With-a-Partner SS and Sexual Functioning | Factor 4 Orgasm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Individual Sexual Satisfaction | 0.475 | |||

| Actual With the Partner(s) Sexual Satisfaction | 0.450 | |||

| Desired Individual Sexual Satisfaction | 0.454 | |||

| Desired With the Partner(s) Sexual Satisfaction | 0.249 | |||

| Orgasm Frequency With a Partner(s) | 0.682 | |||

| Orgasm Frequency in Individual Practices | 0.202 | |||

| Orgasm Importance | 0.523 | |||

| Overall Satisfaction When Orgasm | 0.634 | |||

| Desire Level | 0.323 | |||

| Excitement Level | 0.496 | |||

| Sexuality Importance | 0.395 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 1 | 0.298 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 2 | 0.406 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 3 | 0.323 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 4 | 0.352 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 5 | 0.457 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 6 | 0.471 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 7 | 0.419 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 8 | 0.361 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 9 | 0.433 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 10 | 0.428 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 11 | 0.493 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 12 | 0.521 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 13 | 0.528 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 14 | 0.369 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 15 | 0.377 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 16 | 0.350 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 17 | 0.444 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 18 | 0.342 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 19 | 0.425 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 20 | 0.512 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 21 | 0.493 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 22 | 0.558 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 23 | 0.414 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 24 | 0.429 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 25 | 0.426 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 26 | 0.462 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 27 | 0.465 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 28 | 0.632 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 29 | 0.377 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 30 | 0.484 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 31 | 0.323 | |||

| Factors that affect SS 32 | 0.427 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 1 (P) | 0.728 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 2 (P) | 0.760 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 3 (P) | 0.548 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 4 (P) | 0.554 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 5 (P) | 0.338 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 6 (P) | 0.403 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 7 (P) | 0.502 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 8 (I) | 0.517 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 9 (P) | 0.540 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 10 (P) | 0.424 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 11 (P) | 0.488 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 12 (I) | 0.574 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 13 (I) | 0.557 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 14 (P) | 0.416 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 15 (P) | 0.470 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 16 (P) | 0.616 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 17 (P) | 0.338 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 18 (I) | 0.590 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 19 (I) | 0.542 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 20 (I) | 0.605 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 21 (P) | 0.495 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 22 (P) | 0.465 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 23 (P) | 0.522 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 24 (P) | 0.575 | |||

| Sexual Behaviors that affect SS 25 (P) | 0.383 | |||

| Eigen value | 9.656 | 6.588 | 3.818 | 3.084 |

| % Explained variance | 14.200 | 9.688 | 5.614 | 4.535 |

| % Explained cumulative variance | 34.038 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogallar-Blanco, A.I.; Lara-Moreno, R.; Godoy-Izquierdo, D. Going beyond “With a Partner” and “Intercourse”: Does Anything Else Influence Sexual Satisfaction among Women? The Sexual Satisfaction Comprehensive Index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610232

Ogallar-Blanco AI, Lara-Moreno R, Godoy-Izquierdo D. Going beyond “With a Partner” and “Intercourse”: Does Anything Else Influence Sexual Satisfaction among Women? The Sexual Satisfaction Comprehensive Index. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610232

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgallar-Blanco, Adelaida I., Raquel Lara-Moreno, and Débora Godoy-Izquierdo. 2022. "Going beyond “With a Partner” and “Intercourse”: Does Anything Else Influence Sexual Satisfaction among Women? The Sexual Satisfaction Comprehensive Index" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610232

APA StyleOgallar-Blanco, A. I., Lara-Moreno, R., & Godoy-Izquierdo, D. (2022). Going beyond “With a Partner” and “Intercourse”: Does Anything Else Influence Sexual Satisfaction among Women? The Sexual Satisfaction Comprehensive Index. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10232. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610232