The Mediating Role of Loneliness and the Moderating Role of Gender between Peer Phubbing and Adolescent Mobile Social Media Addiction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Peer Phubbing

2.2.2. Loneliness

2.2.3. Mobile Social Media Addiction

2.3. Main Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Testing for the Mediation Model of Loneliness

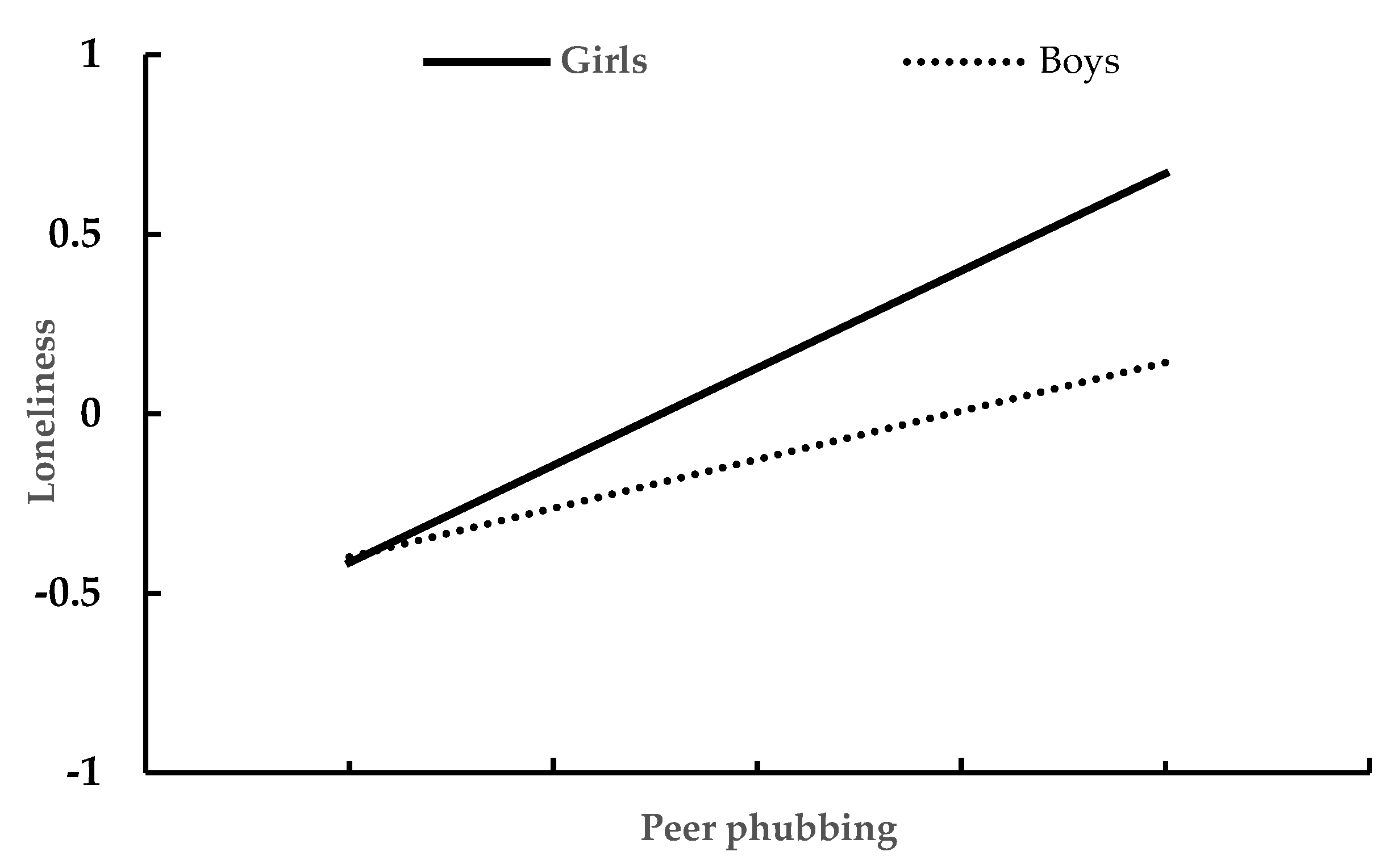

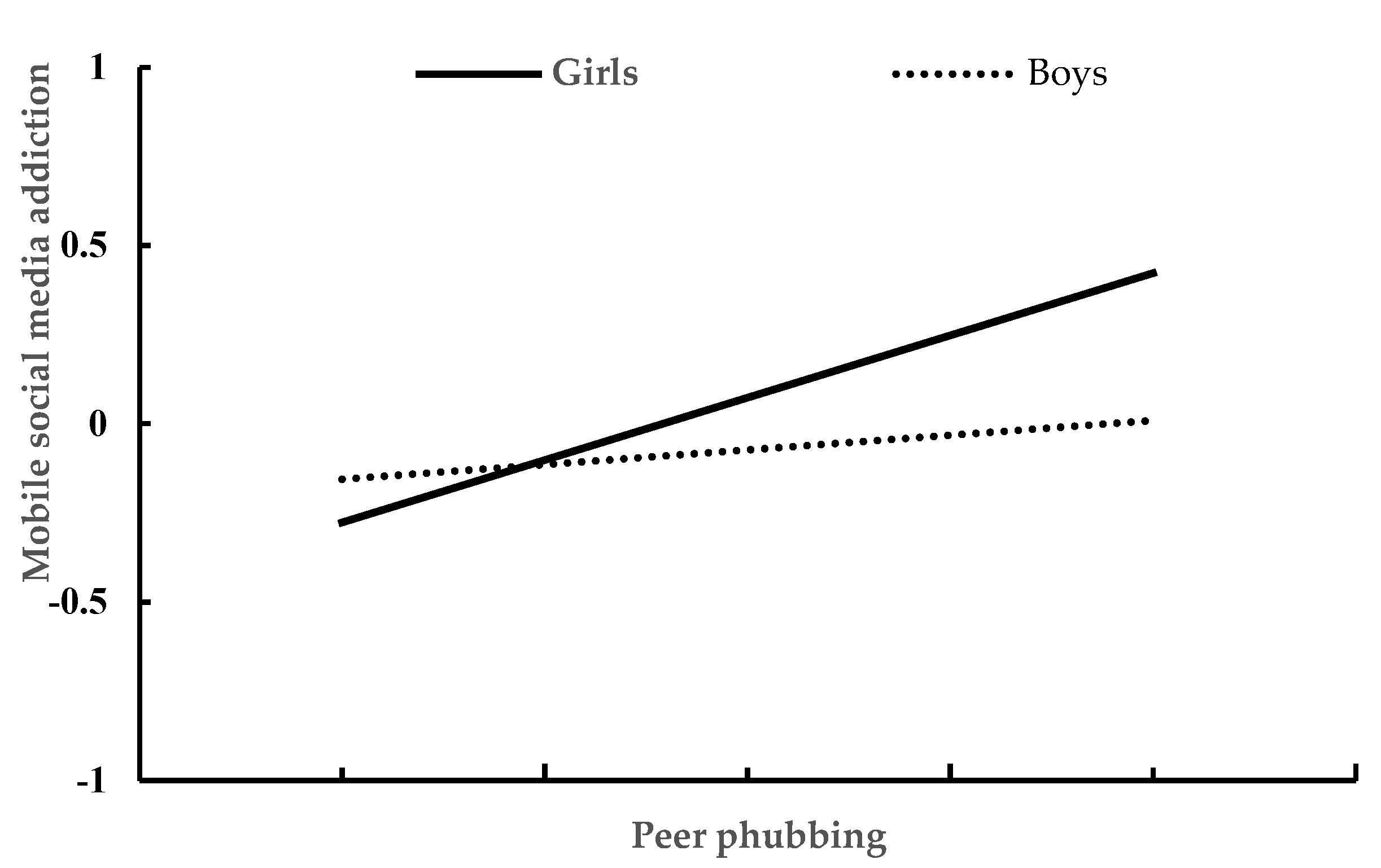

3.3. Testing for the Moderated Mediation Model of Loneliness and Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balakrishnan, J.; Griffiths, M.D. Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Lau, Y.C.; Chan, L.; Luk, J.W. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021, 114, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Xu, X.P.; Yang, X.J.; Xiong, J.; Hu, Y.T. Distinguishing different types of mobile phone addiction: Development and validation of the Mobile Phone Addiction Type Scale (MPATS) in adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Dong, Y.; Luo, M.; Mo, D.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, H. Investigating the impact of mobile SNS addiction on individual’s self-rated health. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Yu, L.; Luqman, A. Understanding the formation mechanism of mobile social networking site addiction: Evidence from WeChat users. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.E.; So, H.; Han, S.P.; Oh, W. Excessive dependence on mobile social apps: A rational addiction perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 27, 919–939. [Google Scholar]

- Nikhita, C.S.; Jadhav, P.R.; Ajinkya, S.A. Prevalence of mobile phone dependence in secondary school adolescents. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Lei, L. Peer relationship and adolescent smartphone addiction: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating role of the need to belong. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiorka, A.; Pantic, I. Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ye, B.; Yu, L. Peer phubbing and Chinese college students’ smartphone addiction during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of boredom proneness and the moderating role of refusal self-Efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukeboom, C.J.; Pollmann, M. Partner phubbing: Why using your phone during interactions with your partner can be detrimental for your relationship. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; David, M.E. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Yao, L.; Wu, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, L.; Sun, X. Parental phubbing and adolescent problematic mobile phone use: The role of parent-child relationship and self-control. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; He, D. Parents’ phubbing increases Adolescents’ Mobile phone addiction: Roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 105, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Ji, S.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Lei, L. Peer phubbing and social networking site addiction: The mediating role of social anxiety and the moderating role of family financial difficulty. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 670065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Pers. Relat. 1981, 3, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Y.; Kutlu, M. The Relationship between loneliness and depression: Mediation role of Internet addiction. Educ. Process Int. J. 2016, 5, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, H. Loneliness and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of boredom proneness and self-control. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y. Childhood maltreatment and mobile phone addiction among Chinese adolescents: Loneliness as a mediator and self-control as a moderator. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirani, A. On the relationship between loneliness and social support and cell phone addiction among students. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 5, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, R.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Zhou, X. Social isolation, loneliness, and mobile phone dependence among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Roles of parent–child communication patterns. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, V.; Gioia, F.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: The role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 586222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Day, E.B.; Heimberg, R.G. Social media use, social anxiety, and loneliness: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 3, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Bullock, A.; Liu, J.; Coplan, R. Unsociability, peer rejection, and loneliness in Chinese early adolescents: Testing a cross-lagged model. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 41, 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, S.J.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Duffy, A.L.; Barber, B.L. Internalizing symptoms and loneliness: Direct effects of mindfulness and protection against the negative effects of peer victimization and exclusion. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2020, 44, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Hahn, S. Age and gender differences in loneliness during the COVID-19: Analyses on large cross-sectional surveys and emotion diaries. PsyArXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.M.; McDonald, A.J.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Wells, S.; Nigatu, Y.T.; Jankowicz, D.; Hamilton, H.A. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with age, gender and their interaction. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Chang, J.H. Gender differences in the association of smartphone use with the vitality and mental health of adolescent students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 66, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Yang, X.J.; Hu, Y.T.; Zhang, C.Y. Peer victimization, self-compassion, gender and adolescent mobile phone addiction: Unique and interactive effects. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Wang, X.L.; Ma, H. Handbook of Mental Health Assessment; Chinese Mental Health Journal Press: Beijing, China, 1999; pp. 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Kanjo, E.; Crook-Rumsey, M.; Kibowski, F.; Wang, G.Y.; Sumich, A. Problematic mobile phone use and addiction across generations: The roles of psychopathological symptoms and smartphone use. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2018, 3, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacis, L.; De Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017, 6, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Yang, S.; Shin, C.S.; Jang, H.; Park, S.Y. Long-term symptoms of mobile phone use on mobile phone addiction and depression among Korean adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, E.B. Gender differences in Internet use patterns and Internet application preferences: A two-sample comparison. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2000, 3, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, A.M.; Guadagno, R.E.; Muscanell, N.L.; Dill, J. Gender differences in mediated communication: Women connect more than do men. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Ervin, K.S.; Gardner, P.D.; Schmitt, N. Gender and the Internet: Women communicating and men searching. Sex Roles 2001, 44, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdie, V.; Downey, G. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent girls’ vulnerability to relationship-centered difficulties. Child Maltreatment 2000, 5, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, E.G.; Hare, A.; Allen, J.P. Rejection sensitivity in late adolescence: Social and emotional sequelae. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 959–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone-Lopez, K.; Esbensen, F.A.; Brick, B.T. Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2010, 8, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonica, C.; Arnold, D.H.; Fisher, P.H.; Zeljo, A.; Yershova, K. Relational aggression, relational victimization, and language development in preschoolers. Soc. Dev. 2003, 12, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Group | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer phubbing | Boys | 2.728 | 0.895 | −0.723 | 0.470 |

| Girls | 2.773 | 0.917 | |||

| Loneliness | Boys | 1.890 | 0.569 | −4.411 | <0.001 |

| Girls | 2.089 | 0.734 | |||

| Mobile social media addiction | Boys | 2.409 | 1.213 | −2.415 | <0.01 |

| Girls | 2.707 | 1.295 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer phubbing | 2.753 | 0.907 | — | 0.343 *** | 0.154 *** |

| 2. Loneliness | 1.999 | 0.671 | 0.548 *** | — | 0.245 *** |

| 3. Mobile social media addiction | 2.571 | 1.267 | 0.508 *** | 0.433 *** | — |

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile social media addiction | Constant | 0.001 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Age | −0.097 ** | 0.031 | −3.154 | <0.01 | |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.170 *** | 0.037 | 4.575 | <0.001 | |

| Peer phubbing | 0.339 *** | 0.035 | 9.828 | <0.001 | |

| Loneliness | Constant | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Age | −0.091 ** | 0.031 | −2.954 | <0.01 | |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.017 | 0.033 | 0.534 | 0.594 | |

| Peer phubbing | 0.453 *** | 0.037 | 12.375 | <0.001 | |

| Mobile social media addiction | Constant | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Age | −0.074 * | 0.030 | −2.483 | <0.05 | |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.166 *** | 0.035 | 4.684 | <0.001 | |

| Peer phubbing | 0.225 *** | 0.037 | 6.033 | <0.001 | |

| Loneliness | 0.252 *** | 0.039 | 6.533 | <0.001 |

| Regression Models | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator variable model for predicting loneliness | ||||

| Constant | −0.004 | 0.030 | −0.125 | 0.901 |

| Age | −0.078 | 0.031 | −2.525 | 0.012 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.488 | 0.626 |

| Gender | 0.256 *** | 0.060 | 4.259 | <0.001 |

| Peer phubbing | 0.448 *** | 0.034 | 13.021 | <0.001 |

| Peer phubbing × Gender | 0.300 *** | 0.069 | 4.336 | <0.001 |

| Dependent variable model for predicting mobile social media addiction | ||||

| Constant | −0.004 | 0.031 | −0.121 | 0.904 |

| Age | −0.071 | 0.030 | −2.380 | 0.018 |

| Gender | 0.147 * | 0.064 | 2.302 | <0.05 |

| Peer phubbing | 0.238 *** | 0.035 | 6.732 | <0.001 |

| Loneliness | 0.212 *** | 0.040 | 5.293 | <0.001 |

| Peer phubbing × Gender | 0.296 *** | 0.066 | 4.465 | <0.001 |

| Conditional direct effect analysis at values of the moderator (gender) | β | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Boys | 0.077 | 0.051 | −0.023 | 0.176 |

| Girls | 0.373 *** | 0.046 | 0.282 | 0.464 |

| Conditional indirect effect analysis at values of the moderator (gender) | β | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Boys | 0.060 ** | 0.015 | 0.035 | 0.095 |

| Girls | 0.124 *** | 0.025 | 0.078 | 0.178 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.-P.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Li, Z.-H.; Yang, W.-X. The Mediating Role of Loneliness and the Moderating Role of Gender between Peer Phubbing and Adolescent Mobile Social Media Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610176

Xu X-P, Liu Q-Q, Li Z-H, Yang W-X. The Mediating Role of Loneliness and the Moderating Role of Gender between Peer Phubbing and Adolescent Mobile Social Media Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610176

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiao-Pan, Qing-Qi Liu, Zhen-Hua Li, and Wen-Xian Yang. 2022. "The Mediating Role of Loneliness and the Moderating Role of Gender between Peer Phubbing and Adolescent Mobile Social Media Addiction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610176

APA StyleXu, X.-P., Liu, Q.-Q., Li, Z.-H., & Yang, W.-X. (2022). The Mediating Role of Loneliness and the Moderating Role of Gender between Peer Phubbing and Adolescent Mobile Social Media Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610176